The novel is a shared space in which imagination converges with knowledge, dreams with thought, and myth with lived reality. A close reading of contemporary Arabic fiction—particularly women’s writing—reveals a spectrum of philosophical perspectives extending across the Arab world, reflected in narrative works that shape readers’ sensibilities and broaden their cognitive horizons.

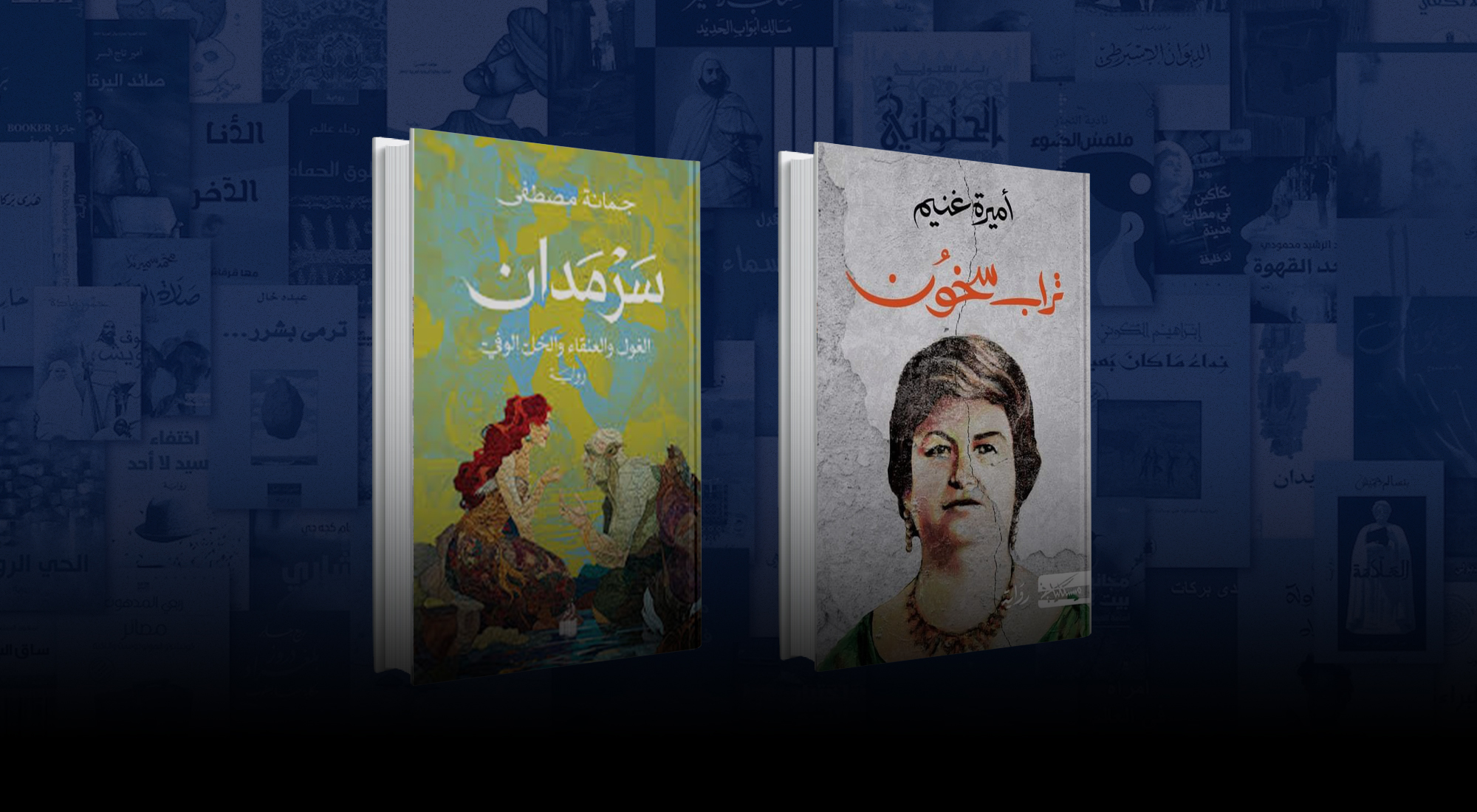

Among the most notable of these works is Turab Sakhoon (Hot Soil) by the Tunisian author Amira Ghannem, a specialist in translation and linguistics at the University of Tunis, recipient of the Arab Literature Prize from the Arab World Institute in Paris, and nominee for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF). The novel probes questions of memory, power, and choice through the evocation of Habib Bourguiba and Wassila Ben Ammar, with “hot soil” functioning as a metaphor for what the earth conceals—pain, secrets, and the intricate corridors of an unextinguished memory.

The second novel, Sarmadan, by the Jordanian–Palestinian writer and poet Jumana Mustafa, draws on the supernatural, mythic, and fantastical as the foundation of its narrative world. Mustafa—based in Jordan, known for several poetry collections, and director of the Khan al-Fonoun Festival in Amman—constructs a universe where mythical beings coexist while confronting an existential threat posed by the human realm. The novel raises profound questions of existence, nonexistence, and belief within a shifting, liminal space between worlds.

This study seeks to analyze the philosophical orientations embedded within these two novels by examining the nature of the philosophical discourse woven into their narrative structures and its linguistic, symbolic, and semantic expressions. It also considers the extent to which these perspectives shape the consciousness of the contemporary Arab reader. Central to this inquiry is a guiding question:

Can a comprehensive cultural and educational consciousness be formed without the presence of the Arabic novel as a foundational element in intellectual and aesthetic development?

Philosophy and the Novel

The novel is a distinctive form of human expression, one in which the narrator constructs a narrative world through voice, rhythm, and the internal logic of events, supported by descriptive cues and character development. These elements work together to reveal both the visible and the concealed layers of the text. When examined through its symbolic and semantic structures, the philosophical presence within the novel emerges clearly—as a means of exploring the human condition, the world, and the nature of existence.

Researcher Mohamed al-Idrissi argues that the novel simultaneously contains both dream and nightmare, functioning as a space in which freedom, anxiety, and existential questioning unfold. Writer Fawzi Boukhris similarly maintains that dreams serve as a pathway to the depths of the self and to realms of freedom, though they may also lead to states of meaninglessness or deferral. From another perspective, scholar Andrew Laird notes that philosophical myth illuminates the human dimension of narrative, as everyday details within the text are imbued with symbols, questions, and dialogues that project an intellectual vision in a world oscillating between reality and imagination.

The relationship between philosophy and the novel is longstanding. Many philosophers have ventured into fictional writing—among them Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, Dostoevsky, Mahmoud al-Masadi, and Ibrahim al-Koni—using narrative as a vehicle for philosophical inquiry. In the history of Arab intellectual thought, Ibn Tufayl’s Hayy ibn Yaqzan (12th century) stands as an early example of philosophical narrative, presented in the form of a contemplative allegorical tale.

Existentialist thought, in particular, evolved in the modern era through Kierkegaard, Martin Heidegger, and Camus, though its deeper roots can be traced back to the dialogues of Socrates, the writings of St. Augustine, and later to the mystical philosophy of al-Suhrawardi, who explored the degrees of existence, the illumination of knowledge, and the metaphysics of light.

Philosophical expression in fiction takes multiple forms. Some authors articulate philosophical ideas directly within the narrative, while others rely on symbolism, metaphor, allusion, and other figurative strategies. This diversity shapes how deeply the philosophical dimension permeates a novel and how profoundly it affects the reader.

A review of the existentialist tradition reveals that existentialism itself defies a single definition. It spans a broad spectrum—ranging from individual to cosmic existentialism, and from absurdism to nihilism, as well as the assertion or negation of meaning. This fluidity should not be viewed as a limitation; rather, it underscores that philosophy within the novel does not provide fixed answers. Instead, it opens a space for inquiry, possibility, and the creation of meaning, rather than the mere delivery of predetermined conclusions.

Genre and the Philosophical Dimension in the Novel Sarmadan

Does total existence transcend meaninglessness and irrationality in the world of Sarmadan?

The term sarmad denotes eternity and boundlessness. In Sarmadan, eternity is not merely a duration but a mode of being: myths and legendary creatures persist endlessly, yet their existence differs fundamentally from human life.

Within this world dwell the ghoul, the guardian of humanity, al-Khill al-Wafī (the loyal companion), the nymph Sanqabasiya, Farhad, the ruler Absun, the inhabitants of the mirrors, the talking animals endowed with wisdom, and the Tree of Wishes.

These mythical beings possess multiple forms of consciousness—pleasure, love, reflection, joy, and six additional modes—each constituting the vital force that animates their world. Time in Sarmadan is measured differently: a single year consists of the passing of forty moons. At the end of one such year, catastrophe strikes when the nymphs disappear, plunging the mythical world into terror.

In the aftermath, Kleib al-Ghoul, the Oracle of Najd, and Farhad persist in searching for the threat undermining their existence as their supernatural attributes begin to fade. Through risk and perseverance, they manage to cross into the human realm, asserting their mythic identities before returning to complete the “seventh consciousness” of Sarmadan—a final stage in resisting extinction and standing firm against external forces.

From these characteristics, it becomes evident that the novel constructs a form of total existence—one that is abstract, immaterial, and unbound by rational constraints. Philosopher al-Suhrawardi describes such a realm as the domain of “abstract intellects,” where impossibility itself becomes a luminous presence permeating existence, while darkness is not annihilation but the state of a mind devoid of belief. Similarly, in Augustine’s philosophy, the absence of faith constitutes evil, while the annihilation confronting all beings is, paradoxically, the moment that awakens awareness of existence—an idea echoed in the mystical thought of al-Hallaj.

In the realm of art, Umm Kulthum famously sang: “If faith is lost, annihilation becomes its companion.”

Faith, in this sense, revealed itself when the legends of Sarmadan encountered the inevitability of death—a moment that granted them complete awareness. The characters believe in what defies belief; impossibility is a defining feature of the eternal world, which cannot endure without conviction and heightened consciousness. Kleib al-Ghoul’s unwavering love for Sanqabasiya allows him to perceive, with the eye of inner knowledge, the impending disappearance of the nymphs long before others recognize the threat—but all in vain, until the fortieth moon finally falls.

Panic spreads across Sarmadan, deepening the inhabitants’ belief in and awareness of their own existence. In response, King Absun and the Council of Madmen rise to confront the looming danger. Figures like the Tree of Wishes and the soothsayer act not through reason but through emotion, initiating what resembles a collective mobilization to save their imagined world.

Their success—rooted precisely in their irrationality—signals the triumph of imagination over dissolution. As Miguel de Unamuno observes:

“An idea is something cold and rigid—a vibration of the will. Mental action does not occur in human beings without an element of emotion and willpower.”

Theoretical Framework

Existential philosophy—whether articulated in its individual or collective form—rests on two fundamental pillars: choice and annihilation. Choice represents the apex of human freedom, the moment in which self-awareness becomes evident through an individual’s capacity to adopt a position toward the world. Annihilation, by contrast, marks the point of deepest existential realization, when a human being—or any conscious being—confronts the meaning of existence and its boundaries, including the possibility of nonexistence.

An analysis of the two novels under study reveals that existentialism manifests in two contrasting yet complementary modes:

- individual existentialism in Turab Sakhoon,

- and cosmic or total existentialism in Sarmadan.

In Turab Sakhoon, escape becomes a return to the self—a cognitive act that does not negate existence but seeks to reclaim and reinterpret it. In Sarmadan, by contrast, meaninglessness does not signify unconsciousness; rather, it becomes an integral component of an imagined, expansive form of existence in which mythical beings transcend the limits of rationality and attain a consciousness rooted in faith and intuition rather than abstract logic.

Thus, each novel proposes a distinct mode of philosophical expression:

- Turab Sakhoon stages the self in confrontation with itself,

- while Sarmadan explores existence in confrontation with the universal and the metaphysical.

Between these two trajectories emerges a critical reading that understands both novels as a contemporary extension of existential thought—not as a fixed philosophical system, but as an open field of inquiry. In this sense, the novel becomes a laboratory for examining the meaning of humanity, its modes of being, and its forms of awareness.

Place and Time

Memory in Turab Sakhoon appears not as a metaphorical or emotional construct but as a physical, living presence embedded within the very soil of the narrative. The secret recordings in the novel are interwoven with popular songs drawn from collective memory—such as the refrain “Let him say what matters”—creating a narrative technique through which personal memory merges with national and social memory. This fusion produces a layered temporal fabric in which the past is continually reconstructed within the present.

This temporal complexity is reinforced by multiple narrative devices, including old letters and flashbacks, such that a single moment from the past reverberates through and reshapes all subsequent moments in the protagonist’s life. Despite the apparent oscillation between temporalities, the narrative voice ultimately stabilizes within a present that transcends the conventional notion of the “now.” In Martin Heidegger’s formulation, the present is not confined to the immediate moment; rather, it encompasses what has been, what is, and what may yet be—an open horizon of possibilities through which past and future are continually reconfigured within a single existential field.

Critic Mounia Kara Biban observes that the epistolary structure in Turab Sakhoon functions as an extension of a prior dialogue, enhancing the narrative’s inherently dialogic quality. The reader senses this continuity in the rhythmic interconnection of events, as illustrated in the scene narrated by Wasila during her attempted escape:

“Before I could breathe a sigh of relief… we heard a thud on the back that shook me to my core.”

This sudden sound becomes a portal into memory, transporting Wasila back to 1948, when she attempted to meet Bourguiba under the guise of pilgrimage. She reflects:

“I realize that those days, whose bitterness was outweighed by their sweetness… were decisive in steering my life toward the path it ended up on.”

Here, past, present, and future converge into a single emotional instant, making time itself a constitutive element of identity rather than an external frame.

In Sarmadan, memory assumes an entirely different dimension—one liberated from materiality. As the text states:

“Memory can become a heavy burden on light new beginnings.”

The mythical beings in this world encounter one another across dreams, the human realm, and their own imagined sphere. Yet time in Sarmadan does not allow for the accumulation of experience; instead, memory is erased through a process known as sensory folding, enabling beings to commence a new existence unburdened by history—as if authentic existence can only begin once memory has been stripped away.

This idea is embodied in the character Serjana, who opens the novel by declaring: “I do not exist.”

And concludes with: “I am not real… but my happiness is.”

The irony here reveals that meaning in Sarmadan is not anchored in material reality, but in the awareness of its absence. Serjana is absent from historical existence yet fully present in the realm of myth, situating her identity between reality and unreality. In this context, birth in Sarmadan becomes a metaphysical event: disappearing from the material world is equivalent to being born into a timeless one.

This conceptualization intersects with Heidegger’s understanding of nothingness—not as a void, but as an epistemological horizon that reveals the truth of existence. Through the confrontation with nothingness, the fundamental questions of being and meaning reemerge.

Thus, place and time in both novels function not merely as technical narrative elements but as philosophical architectures expressing conceptions of existence, memory, and identity. In Turab Sakhoon, time acts as an agent of resistance and restoration; in Sarmadan, it becomes a force of erasure and renewal. Between these two visions arises a narrative discourse that affirms that existence cannot be understood apart from place and time, but must be apprehended through them as intertwined structures that redefine the meaning of being itself.

Textual Issues

In both novels, the narrative discourse converges on the theme of conflict with the other, framing it not as a merely social or emotional tension but as an existential challenge. In Turab Sakhoon, the protagonist declares:

“He saw me as an enemy when I was his shield, and with his own hand he broke his bow and arrows, then drove the broken shaft into my heart.”

In Sarmadan, the response echoes with philosophical resonance: “Adversaries offer us a form of life.”

Taken together, these statements suggest that enmity is not, at its core, an expression of hostility. Rather, it is a condition that reveals the vulnerability of the self or its capacity for resistance. The other—cast as the adversary—becomes a catalyst that compels the self to reconsider the boundaries of identity and the legitimacy of its own existence.

From an intellectual standpoint, both texts pose a central question: Is risk a prerequisite for authentic existence? Confronting evil, darkness, or threat becomes a metaphor for confronting the self. Any desire that stands outside the will of the self is perceived as hostile to its essence—an idea that aligns with Martin Heidegger’s concept of “fallenness” (Verfallen), where the self loses its authenticity by dissolving into the collective, becoming an echo of others rather than an autonomous entity.

Thus, conflict in the two novels is not simply a plot device but a philosophical lens through which to interrogate questions such as:

- Is the self realized within conflict, or through transcending it?

- Can the self fully become itself without encountering the other?

Within this framework, the adversary transforms from a threat into an existential necessity. The self can assert its uniqueness and presence only through an encounter with that which challenges, opposes, or destabilizes it. Risk-taking therefore becomes not only a movement beyond danger but also a movement beyond fallenness—toward an existence that is genuine, singular, and self-affirming.

Applied Framework

Having examined anxiety, mortality, time, space, and both individual and collective modes of existence, we now turn to the events, symbols, vocabulary, and characters that embody these philosophical concepts in practice.

“There I saw him, lying under the sun amid a pile of stones.” (Turab Sakhoon)

We begin with seemingly marginal characters in Turab Sakhoon whose roles nonetheless reinforce the novel’s existential dimensions. Among them is the old sailor, who deceives al-Mājida by exploiting her affection for dolphins and her fascination with the Dionysian myth in which sailors are transformed into whale-like beings endowed with human qualities. Her belief in the symbolic link between the purple birthmark on Bourguiba’s chest and the shape of a dolphin further deepens her susceptibility.

Al-Mājida initially argues with the sailor but soon listens attentively as he recounts stories from his past, including encounters with dolphins—or danfirs, in Tunisian dialect—during a storm. She yields fully to his narrative, hoping it might reveal what she longs for. Yet when she later shares the story with Bourguiba, his response is blunt and shattering, dismantling her idealized vision:

“This is not a mole, Bahulula, and it is not a dolphin… Do you understand oppression?”

His answer articulates a general or external truth but simultaneously opposes her inner truth, generating a tension that propels her toward insistence, resistance, and self-assertion.

This dynamic recalls Sartre’s conception of the Other as a source of existential conflict—not merely through hostility, but through limitation and judgment. As he famously writes in No Exit: “Hell is other people.”

The Other assigns definitions, passes judgments, and inflicts existential pain, becoming an obstacle the self must confront in its struggle to exist authentically.

A similar existential revelation arises through the character of Um Wasila, who disguises herself as a farm worker, “Aunt Fatima,” in preparation for meeting Suad. Wasila reflects:

“My mother’s name, may God have mercy on her, and she chose for me the best activities in my heart over the job of the first lady.”

Here, the imagery of dolphins and the recollection of agricultural life evoke hidden layers of Wasila’s identity—aspects no one else perceives but which shape her internal landscape.

In Sarmadan, we encounter another set of figures who embody existential struggle: the nymphs, trapped in the human world yet destined to return to the mythic realm once they have attained complete awareness. Their transformation signals a transition from constraint to self-realization:

“Under the light of the moons… each of them donned her earth-colored human dress, and the beauties emerged from the water… stumbling a little before bursting into laughter and tears of intense joy.” (Sarmadan)

Illuminated by the moons, the nymphs shed the limitations of water, gain legs, wear earthly garments, and begin to walk—an expression of existence realized through the passageway of mortality.

At the story’s conclusion, a human character named Mubarak appears, having drunk from the magical tears of the green goats:

“He found a small bottle containing a drop or two of water, and his earthly dream became his eternal existence.”

These tears function as a drug transporting the drinker into the dream realm, an antidote to reality—as though reality itself has become an illness requiring escape into imagination. Mubarak encounters the phoenix, strange towers, mystical children, and the emerald courtyard. Unable to withstand the visions, he faints and returns to reality:

“When he woke up, he was in the desert near his car and the sheep, so he began to cry and tried to sleep again to no avail, while the sheep watched him.” (Sarmadan)

Mubarak might have embraced the myths and entered Sarmadan fully, but he refuses to relinquish his former memories, and thus is expelled back into the world of the real.

This aligns with Kierkegaard’s insight that choice is defined by exclusion: to choose one possibility requires rejecting countless others.

Existence is choice—and choosing everything is equivalent to choosing nothing.

Narrative Comparison and Symbols

In Studies in Existential Philosophy, Abdulrahman Badawi presents the vision of the Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno, who asserts that the human being is an end in himself, not a means, and that his deepest aspiration is immortality. According to Unamuno, one of three paths confronts the human condition: despair may prevail; or one may be convinced that some part of oneself will endure; or certainty may remain elusive—leaving struggle as the only viable response.

Unamuno elaborates:

“It is based on the absurd… the constant struggle for survival. But it is essentially a struggle, and the only outcome of this struggle is the defeat of man, yet this defeat is itself the most magnificent victory.”

This vision resonates with the philosophical logic of both novels. Yet the struggle manifests differently: in Turab Sakhoon, it takes the form of escape, whereas in Sarmadan, the struggle is one of transcending the mind—that is, rising above rational acknowledgment of mortality.

Both novels weave the dream into their narrative structures, though in distinct ways. In Sarmadan, dreams recur frequently and form part of the very fabric of the characters’ existence. In Turab Sakhoon, the psychological atmosphere intensifies through a vocabulary of unrest—tension, betrayal, obsessions, delusions—culminating in the notion of terrible nightmares. In a pivotal moment of emotional clarity, Wasila declares:

“Time did not break me; indifference broke me.”

The motif of breaking is a central symbolic thread in Turab Sakhoon. The plan to travel to Bourguiba’s palace represents a break from censorship. The narrative repeatedly breaks silence through remembered scenes, and the dated letters function as a permanent record of ruptured time and place.

In Sarmadan, breaking is embodied through the mirrors with golden frames, which serve as channels of communication. Yet Kleib al-Ghoul’s very gaze shatters them. He is forbidden to look into them at all, for breakage is inherent in their nature; they are always awaiting the moment—and the agent—of their fracture.

Symbolic Architecture in Turab Sakhoon

The novel abounds in symbolism, perhaps most prominently through the old metal belt that recurs throughout the story. It is the one that called out to Wasila from the middle of a pile of stones,

When the protagonist first fastens it around her waist, it refuses to open:

“It was as if locked by an invisible clasp… it stretched and snapped back like a coil. No one could remove it, and I said: ‘It fits me.’”

After I tried—and after everyone else had tried—I turned to the leader, Bourguiba, who removed the belt from her waist, saying:

Later, when Bourguiba releases the belt, he remarks:

“No doubt there is something of me in it.”

Bourguiba’s intervention suggests that whatever freedom is offered is partial and incomplete. The belt remains a psychological burden even after its literal removal—an emblem of imposed constraint that lingers in the mind. It illustrates how the self instinctively distrusts anything that obstructs its freedom, transforming escape from a voluntary act into an involuntary reflex driven by the desire to reclaim agency.

In the imagined world of Sarmadan, once we discern the constituent elements of its populace and rulers, along with the defining features of its broader landscape—features that function as symbolic engines driving the narrative toward a form of spiritual emancipation from the constraints of rational consciousness—we encounter the so-called political center of the “madmen” and their hollow, deserted headquarters.

“On the second floor lives Absun, and on the third is the balcony from which he and the soothsayer address the people. The remaining eight floors are mostly empty.”

The emptiness symbolizes the hollowness of the laws governing their world—laws restricting unions between races or prohibiting the nymphs from crossing water channels. These laws, like the empty tower, lack substance, fairness, or legitimacy.

After the salvation of Sarmadan from annihilation, Absun—himself secretly bonded to a being from the golden mirror—announces the abolition of these laws, granting the inhabitants a new freedom that enables them to attain full consciousness at a climactic moment in their existence.

Heidegger distinguishes between knowledge of existence and awareness of existence—the latter being a complete openness to the origin of meaning. The symbols and events of both novels trace this path toward existential openness.

As explored earlier, key concepts of existential philosophy permeate both novels: freedom as the affirmation of existence without falling; choice grounded in existential awareness; truth and the illumination of faith; escape from adversaries and from linear time into an existential present; and the self beyond phenomena, reaching toward the order of abstract, irrational being

Through their events, characters, and symbolic structures, Turab Sakhoon and Sarmadan carry these philosophical keys with remarkable narrative coherence.

Philosophical Differences Between the Characters in Turab Sakhoon and Sarmadan

In Turab Sakhoon, the character of al-Mājida—embodied through Wasila Ben Ammar—represents a model of the individual self that attains awareness through experience, confrontation, and deliberate choice. Her existence is shaped by intentional acts: resistance, escape, and silence. These actions reflect the form of existential freedom articulated by Heidegger and Camus, in which existence is an active assertion grounded in self-awareness, responsibility, and personal agency. Within the narrative, Wasila flees from memory into the present and returns from time into the self; reality and temporality function as stations along a journey of transformation, continually reshaped according to her evolving consciousness.

In Sarmadan, the mythical characters—Kleib al-Ghoul, Sarjana, the nymphs, Absun—represent a form of total symbolic existence that confronts annihilation from a cosmic standpoint extending beyond individual experience. The influence of Suhrawardian illuminationism is evident here: light becomes a central metaphor for existence, while annihilation transforms into a pathway toward absolute consciousness. Freedom in this world is achieved by breaking the formal constraints that limit imagination and faith, moving beyond the boundaries of material reality toward a creative imaginary that restores the eternal meaning of existence.

Thus, the characters of Turab Sakhoon embody a realistic, individual human existence, whereas the characters of Sarmadan embody a symbolic, collective, cosmic one. The former derive their consciousness from concrete sensory experience, while the latter draw it from symbolic, supra-real experience. Freedom in Turab Sakhoon is expressed through action, choice, and escape; in Sarmadan, it is realized through faith, the irrational, and heightened consciousness.

Conclusion

The two novels converge on a shared philosophical core: the experience of self-determination within a turbulent world that threatens both meaning and existence. Yet their artistic trajectories diverge in how they explore this essence. Turab Sakhoon begins with the individual as a historical being shaped by memory and lived experience, while Sarmadan moves through symbol, myth, and dream to contemplate collective consciousness and total existence. This contrast does not signal contradiction; rather, it reveals a form of philosophical complementarity in which the individual self and the collective myth coexist as parallel responses to a single question: How is existence achieved?

In Turab Sakhoon, Amira Ghoneim weaves together the realistic and the historical within a humanistic framework that interrogates how time and memory shape the formation of the self. In Sarmadan, Jumana Mustafa constructs a symbolic, mythical world in which imagination becomes the medium for examining consciousness, meaning, and destiny.

In both works, philosophy is not an ornamental gesture nor a superficial thematic layer. It functions as a structural principle that shapes narrative movement and redefines the relationship between language and idea, story and existence.

Modern Arabic literature—with its intellectual depth, narrative richness, and refined allusive techniques—deserves prominent inclusion within philosophical inquiry and academic curricula. It should be studied not merely as an aesthetic tradition but as a field of knowledge that generates questions rather than merely supplying answers.

In its subtle, evocative, and densely layered moments, the Arabic language demonstrates its capacity to convey the visionary and the contemplative, elevating meaning from the level of imagery to that of thought. Here, words become a bridge to the philosophical horizon, and metaphor becomes a mode of truth.

References

Muhammad Al-Idrisi, “Revitalizing the Epistemological Dialogue between Literature, Sociology, and Philosophy,” Bahrain Cultural Magazine (Kingdom of Bahrain, 2021), https://www.academia.edu/48874599/فوزي_بوخريص_تشبيب_الحوار_الإبستيمولوجي_بين_الأدب_والسوسيولوجيا_والفلسفة.

Abdul Rahman Badawi, Studies in Existential Philosophy (Beirut: Dar al-Thaqafa, 1973), 3rd ed.

Muhammad Hussein Bazzi, The Philosophy of Existence in al-Suhrawardi: An Approach to the Wisdom of Illumination (Beirut: Dar al-Amir for Culture and Science, 2009).

Mina Qara Biban, “Correspondence and the Aesthetics of Imagination in Turab Sakhoon by Amira Ghoneim,” Middle East Online (London, 2024), https://middle-east-online.com/التراسلية-وجماليات-التخييل-في-تراب-سخون-لأميرة-غنيم.

Amira Ghoneim, Turab Sakhoon (Tunis: Miskliani Publishing, 2024), 1st ed.

Andrew Leard, “Imagination, Philosophy, and Logical Completion,” Academia (2007), https://www.academia.edu/2494106/Fiction_Philosophy_and_Logical_Closure.

Jumana Mustafa, Sarmadan: The Ghoul, the Phoenix, and the Faithful Vinegar (Dammam: Dar Athar, 2024).