Introduction

Of the more than 3,400 Westerners who left their home countries to join ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria)[1] in 2014 and 2015, it is estimated that 550 were women.[2] Many of these women were teenagers, who the terrorist organization targeted to become child brides for its fighters. The well-trained recruiters appealed to these young women’s sense of “honor” and played upon their naiveté, describing a life of domestic bliss amongst like-minded people in idyllic scenes from territory controlled by ISIS.[3] These campaigns were often conducted through social media, and tended to downplay the state of violence their recruits would be living in.

The reality of the situation for these women was quite different than what they were promised. They not only had to carry out their duties as ISIS brides — cooking, cleaning, giving birth to and raising children — but worked as patrol officers, fighters and prison guards after the terrorist group’s imams issued a “fatwa” allowing it, given that the caliphate was under threat and there were not enough men to protect it.[4] Once recruited, they also became the recruiters; 80% of these women spent most of their day on social media trying to attract new members to the jihadist cause. Their fluency in Western languages gave them a competitive advantage in this task.[5]

The story of Shamima Begum is a case study in the ISIS recruitment of young Western women. In 2015, Begum was 15 years old and lived in the Bethnal Green area in the East End of London, where she went to school and lived with her Bangladeshi parents. She started researching ISIS online, and was soon given explicit instructions from recruiters on how to join the terrorist organization in Syria. “People online were instructing us and, like, coaching us on what to do and what not to do,” she said. She was given “a big list of precise instructions,” including what cover story to use if they were discovered.[6] That year, she and two other schoolgirls from Bethnal Green, Amira Abase and Kadiza Sultana, left the United Kingdom to travel to Raqqa, Syria, to join ISIS.

In 2019, The Times’ war correspondent Anthony Loyd found Begum in a refugee camp in Northern Syria. Begum expressed a desire to return to London, but the UK government revoked her British citizenship on national security grounds, arguing that she was a threat to the country. Begum contested the decision and appealed to have her citizenship reinstated, but her appeals were unsuccessful. In 2021, the Supreme Court of the UK ruled that Begum should not be allowed to return to the UK to pursue her citizenship appeal, stating that she could not have a fair and effective hearing due to the security risks involved. As of now, she is held at the al-Roj camp in northeast Syria.

Rejecting life in the West

People join organizations such as ISIS for religious, psychological, and economic reasons, but the most significant factor affecting Muslim women who join jihadist organizations is religious indoctrination.[7] Many first- and second-generation migrants tend to want to preserve their sense of Islamic identity and pass it on to their children. Most parents of ISIS recruits did not encourage their children to join such organizations, and were not aware of their children’s radicalization, but their strict, often conservative religious ideology likely contributed to their children’s decisions. Some studies suggest that young girls, for example, turn to ISIS as a coping strategy for overcoming an adolescent identity crisis. To liberate themselves from a traditional patriarchy, they turn to a new, seemingly superior, ideology.[8]

Muslims born into immigrant families also usually feel conflicted about their identity because of cultural and religious differences with Western culture, which leaves them more vulnerable to extremist groups.[9] Some of these women face racism and anti-Islamic sentiment in the West, including negative attitudes about the wearing of the hijab or niqab. They might find that they are stereotyped because of their religion, and that portrayals of Muslims in the media are often hostile or insulting. The military campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan after 9/11 created ill will amongst many foreign Muslims, who began viewing Westerners as the “enemy.”[10] ISIS exploited these feelings, arguing in its messaging that fighting the West could be a way to achieve “revenge,” and that every “true Muslim” should feel a duty to defend his or her brothers and sisters. Some women were made to feel guilty about their privileged life in the West, and this triggered a desire to give back; joining ISIS gave them a sense of belonging to a global cause.[11]

These women, including well-educated Westerners, devoted their lives to fighting for a new “caliphate” in the name of Islam. They heeded the call of ISIS militant leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi and traveled to Syria and Iraq, dreaming of joining a utopian community of Sunni Muslims living together under the strict law of Sharia, which they believed honored women in a way that was not possible in the West.[12] They found a sense of agency and empowerment through their contribution to the Islamic State, and believed their roles as mothers, teachers, or nurses had religious meaning.[13] In the minds of these radicalized women, being married to a fighter enhanced their status, and even if they were to become a widow, they would more easily get a “pass” into heaven.[14]

Young and bored: Profiling women radicals

ISIS recruiters usually targeted young Western girls online, as they tended to be more vulnerable and easily persuaded. A 2016 study supported this; of the 38 women who joined ISIS, the majority of whom were foreigners, the average age of recruitment was 24.3 years old.[15] Some women who already felt alienated from Western society joined ISIS of their own accord, but the typical recruit was first approached online and exposed to radical propaganda. Many of the teenagers who joined ISIS from Europe left their homes in pairs instead of on their own, as having a companion of the same age and ideology made joining more comfortable.

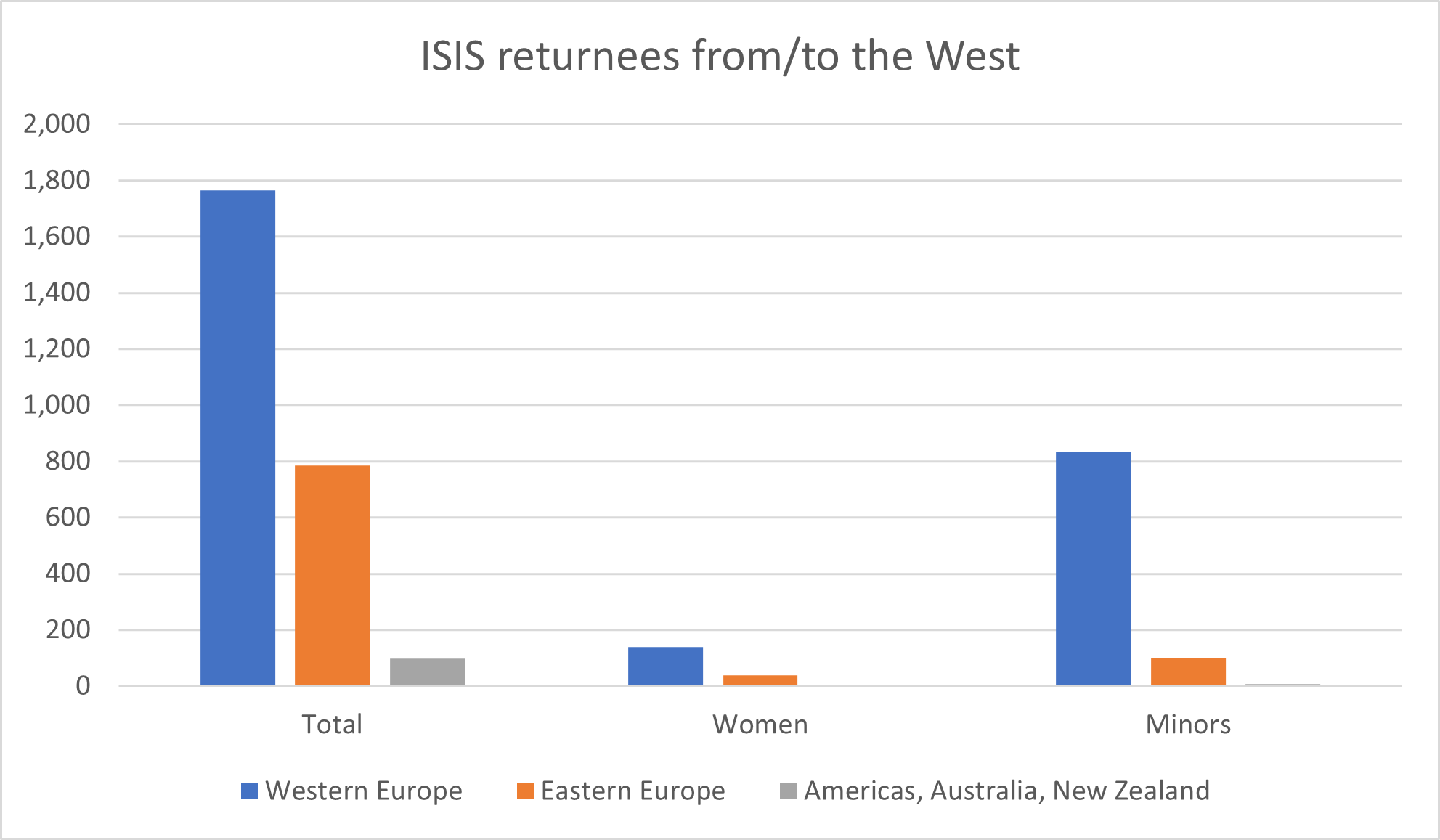

Figure 1. Isis affiliates from the West

Source: International Centre for the Study of Radicalization (2018)[16]

ISIS tended to target their recruiting approach toward women, using messaging that included scenes of landscapes and sunsets, typically in a pink background, to appear “feminine,” as women usually joined ISIS for gender-specific roles.[17] Other propaganda, however, appealed to both men and women, especially messages about religious duty and violent imagery; many female recruits reacted favorably to videos of beheadings and other vicious acts.[18]

Many of these young women felt “bored,” and signing up for a jihadist cause fulfilled a desire for real adventure.[19] Not only was joining a movement an act of rebellion against their environment, but it also gave them the feeling of potentially “changing the world.” ISIS sold a fantasy life to these young, naïve women, offering them the status, safety and sense of belonging that comes from a group. They were drawn to the allure of marrying a foreign fighter, even though these men were up to twice their age.[20] These men were portrayed as “heroes” or “warriors,” and the idea of a strong provider with a common cause seemed appealing, especially in contrast to previous romantic disappointments these women might have had at home.

Figure 2. Isis returnees from and to the West

Source: International Centre for the Study of Radicalization (2018)[21]

Poor economic conditions and social status for foreign Muslim immigrants living in the West made moving to the Middle East more attractive for some ISIS recruits.[22] ISIS recruiters assured young women that if they joined, they would be provided with free housing and financial support for every child they bore.[23] For women, especially for those from middle-upper class homes in the West, the incentives might not have been the most important factor in their choice to join, but knowing they would be taken care of financially could have given them added assurance to leave home.

Stuck in Syria: The tragedy of Shamima Begum

Since the so-called caliphate was torn down in 2017, many of the thousands of foreign recruits who went to Syria to join ISIS have returned home, including 360 British nationals. But Shamima Begum remains in a refugee camp in Syria.

In the time she spent in Raqqa, between 2015 and 2019, Begum married an ISIS militant while still in Syria and gave birth to two children who died in infancy because of illness and starvation. In January 2019, when she was found in al-Hawl, a 39,000-person Syrian refugee camp, she was pregnant again. She told The Times that she wanted to deliver her baby at home, but her citizenship had been revoked because of national security concerns. In February, she gave birth to her son, Jarrah, in the camp. The infant was taken to the main hospital in al-Hasakah city, but his condition swiftly deteriorated, and he died.[24]

How did this tragic story unfold? Begum claims she has evidence that she was subjected to sexual exploitation during her time in Syria. It appears ISIS took advantage of her teenage immaturity and groomed her via the Internet. The question is whether the UK will view her as a young victim of human trafficking and take responsibility for her well-being.[25]

A controversial case: Bring her home or let her rot?

In 2019, the Home Office stated that Begum posed a risk to national security; MI5, the UK security service, believes she still does. At the 2021 appeal of the decision to revoke her British citizenship, Begum was even denied permission to enter the UK so she could be present at the hearing. Attorneys for Begum disputed these rulings before a Special Immigration Appeals Commission (SIAC), but on February 22, 2023, the SIAC determined that Begum was still a security threat and the Home Secretary had the power to strip her of her citizenship. Begum is expected to attempt to take her case to the Court of Appeal.[26]

The question of whether Shamima Begum has a right to return to the UK is a complex and controversial one. She was born a British citizen and is entitled to the right and privileges that entails, but there are responsibilities and duties that go along with citizenship. When a citizen joins a militant group who is the sworn enemy of your birth country, do they forgo their citizenship? Supporters of Begum argue that she was a minor when she left the UK, and that because she was radicalized and manipulated by extremists, she should be allowed to return to the UK to face justice and receive appropriate rehabilitation and support. Opponents argue that Begum made an informed decision to join a terrorist group, and that she poses a significant threat to national security. They contend that allowing her to return to the UK could jeopardize public safety and send the wrong message to other potential terrorists.

Ultimately, the question of whether or not Shamima Begum should be allowed to return to the UK is a matter of ongoing debate and legal interpretation, and it is up to the relevant authorities to make a decision based on the information available and the considerations at stake.

References

[1] ISIS is also known as ISIL (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), and Daesh, its Arabic acronym.

[2] Shiv Malik, “Lured by Isis: How the Young Girls Who Revel in Brutality Are Offered Cause,” The Guardian, February 21, 2015, http://bitly.ws/BXmi.

[3] Amanda N. Spencer, “The Hidden Face of Terrorism: An Analysis of the Women in Islamic State,” Journal of Strategic Security 9, no. 3 (2016): pp. 74-98, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26473339.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ashley Binetti, “A New Frontier: Human Trafficking and ISIS’s Recruitment of Women from the West,” Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace & Security (2015): pp. 1-8, http://bitly.ws/BXmC.

[6] Josh Baker and Joseph Lee, “Shamima Begum Accepts She Joined a Terror Group,” BBC News, January 11, 2023, http://bitly.ws/BXnc.

[7] Anita Perešin, “Fatal Attraction: Western Muslimas and ISIS,” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 3 (2015): pp. 21-38, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26297379.

[8] Simon Bonnet, “Western Women in Jihad, Triumph of Conservatism or Export of Sexual Revolution?” Sciencespo (Spring 2014-2015): pp. 1-34, http://bitly.ws/BY3Z.

[9] “ISIS Foreign Fighters: Why Do Foreigners Join the Caliphate?” Vision of Humanity, http://bitly.ws/BY5M.

[10] Jack McGinn, “Female Radicalisation: Why Do Women Join ISIS,” London School of Economics and Political Science, August 15, 2019, http://bitly.ws/BY5s.

[11] Anita Perešin, “Fatal Attraction: Western Muslimas and ISIS,” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 3 (2015): pp. 21-38, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26297379.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “The Roles of Women in Daesh,” Council of Europe, Committee of Experts on Terrorism, Discussion Paper, 31st Plenary Meeting Strasbourg (France), November 16-17, 2016: pp. 4-5, http://bitly.ws/BY52.

[14] Edwin Bakker and Seran de Leede, “European Female Jihadists in Syria: Exploring an Under-Researched Topic,” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague 6, no. 2 (2015), http://bitly.ws/BY5e.

[15] Anne Speckhard and Molly D. Ellenberg, “ISIS in Their Own Words: Recruitment History, Motivations for Joining, Travel, Experiences in ISIS, and Disillusionment over Time – Analysis of 220 In-depth Interviews of ISIS Returnees, Defectors and Prisoners,” Journal of Strategic Security 13, no. 1 (2016): pp. 82-127, https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.13.1.1791.

[16] Joana Cook and Gina Vale, From Daesh to ‘Diaspora’: Tracing the Women and Minors of Islamic State (London: International Centre for the Study of Radicalization, 2018): pp. 14-15, http://bitly.ws/BXn2.

[17] Council of Europe, “The Roles of Women in Daesh,” Committee of Experts on Terrorism, Discussion Paper, 31st Plenary Meeting Strasbourg (France), November 16-17, 2016: pp. 4-5, http://bitly.ws/BY52.

[18] Seran De Leede, Renate Haupfleisch, Katja Korolkova, and Monica Natter, “Radicalisation and Violent Extremism – Focus on Women: How Women Become Radicalised, and How to Empower Them to Prevent Radicalisation,” European Parliament, Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, 2017: pp. 1-31, http://bitly.ws/BY6I.

[19] Anita Orav, Rosamund Shreeves, and Anja Radjenovic, “Radicalisation and Counter-radicalisation: A Gender Perspective,” European Parliamentary Research Service, April 2016, http://bitly.ws/BY3E.

[20] Anita Perešin, “Fatal Attraction: Western Muslimas and ISIS,” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 3 (2015): pp. 21-38, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26297379.

[21] Joana Cook and Gina Vale, From Daesh to ‘Diaspora’: Tracing the Women and Minors of Islamic State (London: International Centre for the Study of Radicalization, 2018): pp. 14-15, http://bitly.ws/BXn2.

[22] Alex Nowrasteh, “Muslim Immigration and Integration in the United States and Western Europe,” Cato Institute, October 31, 2016, http://bitly.ws/BY3J.

[23] Joana Cook and Gina Vale, From Daesh to ‘Diaspora’: Tracing the Women and Minors of Islamic State (London: International Centre for the Study of Radicalization, 2018): pp. 14-15, http://bitly.ws/BXn2.

[24] Nikhil Kumar, “Who Is Shamima Begum, the Former ISIS Bride Fighting to Win Back Her British Citizenship?” Grid, March 10, 2023, http://bitly.ws/BY6W.

[25] Haroon Siddique, “Shamima Begum Loses Appeal Against Removal of British Citizenship,” The Guardian, February 22, 2022, http://bitly.ws/BY7e.

[26] “Shamima Begum: How Can You Lose Your Citizenship?” BBC News, February 23, 2023, http://bitly.ws/BY6Z.