Bosnia and Herzegovina’s (BiH) three-and-a-half-year civil war ended in 1995 with the U.S.-brokered General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina (a.k.a. the Dayton Agreement). The agreement split most of the country into roughly equal entities to comprise the sovereign Bosnian state. One is the Bosnian-Serb Republika Srpska, with its main city and administrative center being Banja Luka. The other is the Bosnian-Croat and Bosniak Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with its power center being BiH’s capital, Sarajevo. For the past 29 years, BiH has, to the credit of this peace deal, not slid back into another civil war. But the country’s post-1995 political situation has always been extremely complicated with the Daytonian equilibrium holding together a fragile peace.

In February 2022, tensions within BiH worsened because of Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine, raising basic questions about the future of relations between BiH’s various communities and the state’s territorial integrity. The Moscow-backed Bosnian-Serb leadership in Republika Srpska took a pro-Russia stance while the NATO-oriented Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina sided with Ukraine and the West. Ultimately, the conflict in Ukraine heightened longstanding fractures not only in BiH but also elsewhere in the Western Balkans, such as in Kosovo, Montenegro, and Serbia.

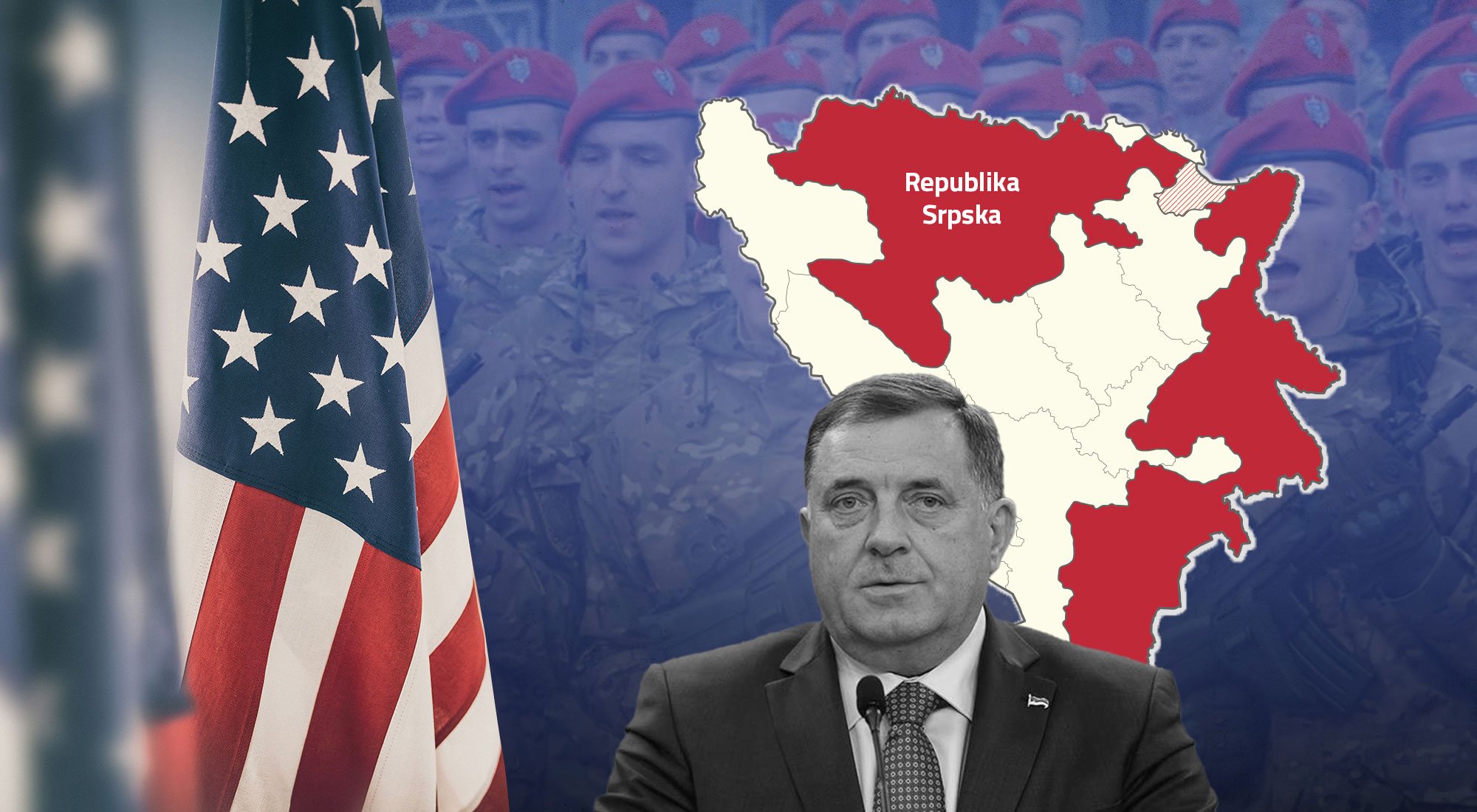

Against this backdrop, tensions have built up between the U.S. and Milorad Dodik, who has been Republika Srpska’s president since 2022. He previously served in this role from 2010 to 2018, before being a member of BiH’s three-person collective presidency from 2018 to 2022. Washington and capitals in Western Europe see the survival of the Dayton Agreement and BiH as a nation-state serving the West’s interests. Dodik’s actions and rhetoric challenge the Bosnian state’s sovereignty and territorial dignity, fueling concern among most NATO and EU members. Ultimately, the West does not want to see Republika Srpska become a “Balkan Transnistria” that empowers Moscow in Europe’s “inner courtyard.”[1]

Dodik’s Statements

An international High Representative maintains responsibility under the Dayton Agreement for overseeing the implementation of the peace accord and has the authority to remove public officials and impose laws on BiH in the interest of upholding the Dayton Agreement. Throughout recent years, the Republika Srpska leadership has become increasingly assertive in its moves that threaten BiH’s territorial dignity, with Dodik repeatedly threatening to secede Republika Srpska from the country while lashing out against the High Representative.

The Bosnian-Serb leader has previously expressed his desire to hold a referendum on Serbian independence from BiH. In 2022, Dodik delayed separatist plans by citing the shocks of the Ukraine war. But not long before Russia began its “special military operation,” Dodik was vowing to withdraw Republika Srpska from BiH’s taxation regimes, key judicial bodies, and armed forces.[2] In June 2023, the dominant Bosnian-Serb legislative body in Banja Luka passed legislation to suspend rulings issued by the BiH constitutional court.[3] The following month, Dodik signed legislation that basically permitted the National Assembly in Banja Luka to disregard decisions by the High Representative, but the High Representative overturned the laws.[4], [5] In December 2023, Dodik said that if Donald Trump wins the 2024 U.S. presidential election, Republika Srpska would formally separate from BiH.[6]

Such threats and actions have long unsettled Western policymakers who perceive Dodik as a destabilizing and problematic actor in the Western Balkans. Officials in the U.S. and much of Western Europe see the upholding of the Dayton Agreement and the preservation of BiH’s territorial integrity as necessary for ensuring peace in southeastern Europe. Within the context of the Ukraine war, policymakers in the West worry about Moscow’s ability to leverage tensions between Banja Luka and Sarajevo in ways that can undermine the interests of Western governments in the Western Balkans. Such dynamics have led to the U.S. and the UK imposing sanctions on Dodik and certain entities in Republika Srpska. Germany has also taken certain actions to pressure Dodik into ending his anti-Dayton conduct.[7]

History of U.S. Sanctions

Three days before Trump’s presidency began in January 2017, Barack Obama’s outgoing administration imposed sanctions on Dodik in response to his obstruction of the Dayton Accords’ implementation. Specifically, this action was a response to the Bosnian-Serb leader violating a ruling by BiH’s Constitutional Court when he held a referendum in September 2016 on a celebration of “The Day of Republika Srpska” for January 9—a move that Washington and Brussels saw as threatening peace in BiH but which Moscow supported.[8] When the Obama administration imposed those sanctions, then-U.S. ambassador to BiH, Maureen Cormack, declared that “Milorad Dodik has defied the Constitutional Court of BiH, violated the rule of law and poses a significant risk of obstructing the implementation of the Dayton Accords.”[9]

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) imposed these sanctions, enabling authorities in Washington to deny Dodik access to any of his property or assets that fall under U.S. jurisdiction. As one U.S. official said at the time, the sanctions are “part and parcel of a result of Dodik’s call for secession, his defiance of the constitutional court and [his] threats to withdraw the Republika Srpska members of the armed forces from the military.”[10] Washington’s sanctions on Dodik remained in place under Trump and Biden’s presidencies, with both administrations even imposing more on the Bosnian-Serb strongman. In July 2017, six months after Trump entered the Oval Office, OFAC designated Dodik with the then-Acting OFAC Director, John E. Smith, accusing Dodik of representing a “significant threat to [BiH’s] sovereignty and territorial integrity” and saying that the sanctions highlight Washington’s “commitment to the Dayton Accords and supports international efforts for the country’s continued European integration.”[11] This designation blocked “any property or interest in property of Dodik within U.S. jurisdiction” and made it so “U.S. persons are generally prohibited from engaging in transactions with him.”[12]

In early January 2022, the Biden-Harris administration continued acting against Dodik in response to his anti-Dayton conduct. At that point, OFAC designated Dodik and Alternativna Televizija d.o.o. Banja Luka (ATV), which is a Banja Luka-based media outlet privately owned by a company with close ties to Dodik’s family.[13] As the U.S. Treasury explained, these designations came in response to Dodik undermining institutions in BiH by “calling for the seizure of state competencies and setting in motion the creation of parallel institutions in…Republika Srpska” and the Bosnian-Serb leader using his power to “accumulate personal wealth through graft, bribery, and other forms of corruption.”[14] U.S. Under Secretary of the Treasury for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Brian E. Nelson declared, “The United States will not hesitate to act against those who pursue corruption, destabilization, and division at the expense of their own people, as well as against those who enable and facilitate this behavior.”[15]

Up until that point, however, Dodik and many in Republika Srpska did not take these sanctions seriously and even mocked Washington’s efforts to pressure Banja Luka. Given Dodik’s lack of assets in U.S. jurisdictions and the fact that he had no plans to visit the United States, such sanctions and designations had little tangible impact on BiH’s Bosnian-Serb entity. However, the picture changed with a new round of sanctions imposed by the Biden-Harris administration in the first half of 2024, ultimately demonstrating to Dodik and other power brokers in Banja Luka that while the American sanctions noose might squeeze slowly, it eventually strangles.

On 13 March 2024, OFAC designated three individuals— Branislav Okuka, Jelena Pajic Bastinac, and Srebrenka Golic—for their alleged roles in facilitating Dodik’s actions that undermine BiH’s Daytonian peace.[16] Three months later, OFAC designated two individuals and seven entities that are major revenue sources for Dodik and his son, Igor Dodik. These two individuals were Djordje Djuric and Milenko Cicic. The seven entities were Infinity International Group d.o.o. Banja Luka, Prointer ITSS d.o.o. Banja Luka Clan Infinity International Group, Kaldera Company El PGP d.o.o., Infinity Media d.o.o., K-2 Audio Services Banja Luka d.o.o., Una World Network d.o.o., Sirius 2010 d.o.o. Banja Luka.[17]

Dodik and other power brokers in Republika Srpska have taken these OFAC designations of 2024 seriously because they have gone after Dodik’s business interests, ultimately targeting his own wealth and power. This pressure from Washington is also taking a significant toll on Republika Srpska’s economy.[18] In response, policymakers in Banja Luka have sought to overcome the impact of Washington’s sanctions by amending the Law on the Investment-Development Bank (IDB).

In July 2024, the National Assembly of Republika Srpska passed a law to “open bank accounts for individuals and companies, conduct domestic payment transactions, and accept deposits” as part of an effort “intended to straighten the position of Republika Srpska,” according to Srdjan Mazalica, a lawmaker from the ruling Alliance of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD).[19] Yet, the U.S. Embassy in Sarajevo clarified that the “sanctions can be applied to any institution, including banks, whether privately or publicly owned, that provide material support to individuals or companies under U.S. sanctions.”[20]

Republika Srpska’s International Backers

Washington’s sanctions have pushed the Bosnian-Serb entity closer to Russia, China, and Hungary. Dodik sees Banja Luka’s relationships with Moscow, Beijing, and Budapest as critical to counter-balancing the effects of U.S. policies aimed at changing the Bosnian-Serb strongman’s anti-Dayton conduct.

Russia is extremely important to Dodik’s position of power and separatist agenda. Arms suppliers in Russia have equipped police forces in Republika Srpska and Russian mercenaries have trained Bosnian-Serb paramilitary organizations.[21] Additionally, Moscow has provided Dodik and other power brokers in Republika Srpska with vast amounts of financial support.[22] In terms of soft-power influence, the Russians have supported Republika Srpska with cultural, religious, and educational backing.[23]

Moscow has also treated Republika Srpska as an independent country. For example, at a security conference in St. Petersburg in April 2024, the Republika Srpska flag stood next to the flags of other countries while Dodik attended the forum.[24] Speaking at the event, the Bosnian-Serb leader blasted the West for recognizing Kosovo’s independence but not recognizing Republika Srpska’s “constitutional rights” while also hailing Russia’s opposition to the U.S.-supported UN resolution on the Srebrenica genocide.[25]

In January 2023, Dodik awarded President Vladimir Putin with Republika Srpska’s highest medal of honor, praising the Russian leadership for “developing and strengthening cooperation and political and friendly relations between Republika Srpska and Russia.”[26] At the awards ceremony in Banja Luka, Russia’s ambassador to BiH, Igor Kalbukhov, said, “We believe that this award is an affirmation of the strategic determination of our relations aimed at strengthening the friendship of our brotherly people.”[27]

In recent years, Dodik has increasingly turned to China as a financial lifeline amid a period of Republika Srpska failing to attract much foreign investment while facing looming debt.[28] An important starting point in Banja Luka’s relationship with Beijing was when Republika Srpska and China formalized their relationship via a cooperation agreement in 2016.[29] In recent years, the Chinese have become increasingly involved in Republika Srpska’s infrastructure and construction projects and power plants.[30]

Although Republika Srpska’s ties with Russia and China are both important, there are differences in these two relationships. Among BiH’s Serbs, views of Russia have much to do with emotion. There are strong cultural, religious, and historic ties that bond them to Moscow. Russia’s opposition to NATO’s bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999 has contributed to Moscow’s image as a benign and brotherly country in the eyes of many citizens of Republika Srpska. Bosnian-Serbs view China strictly through an economic and financial prism without any powerful emotions or cultural and religious factors in play.

Hungary is the most Republika Srpska-friendly EU member. This fact makes Budapest’s relationship with Dodik and other power brokers in Banja Luka extremely important for the Bosnian-Serb entity. Republika Srpska maintains an economic window to the EU via Hungary. In recent years, Budapest has provided BiH’s Serb entity with hundreds of millions of euros in grants, loans, and funding for energy and infrastructure projects.[31] The U.S. sanctions on Dodik and various entities tied to his family have served to push Republika Srpska closer to Hungary.

Officials in Budapest use strong language when accusing Western European countries of stirring up tensions in the Western Balkans. Such rhetoric has come to the point whereby some observers identify Hungary as “a mouthpiece for Serbia and Republika Srpska” within the EU.[32] Hungary has also sided with Serbia and Republika Srpska on contentious political issues pitting Belgrade and Banja Luka against the West. Examples include Budapest opposing Kosovo’s accession to the Council of Europe and the UN General Assembly’s Srebrenica resolution.[33] Hungary has consistently opposed Western sanctions on Dodik and criticized the High Representative for its role in BiH.

On a personal level, Dodik and Orban maintain a close relationship. Their political alliance goes back many years. Orban is one of the very few leaders in the EU and NATO who travels to Republika Srpska and meets with Dodik. Within this context, it was unsurprising in April 2024 when the Bosnian-Serb strongman awarded the Hungarian prime minister the Order of the Republika Srpska award.[34]

Hungary’s importance to the Bosnian-Serb entity will only increase now that it has taken over the rotating six-month presidency of the Council of the European Union. With Hungary serving this role, it is safe to bet that Orban will pursue a pro-Banja Luka and pro-Belgrade agenda, particularly when it comes to sensitive debates about EU enlargement in the Balkans. Nonetheless, many in the West are seeing a “brotherhood in the triangle between Budapest, Belgrade, and Banja Luka” that contributes to views held by many policymakers in Washington and other Western capitals of Orban as a leader who disrupts both the EU and NATO from within.[35] Perceiving Orban to be a Putin-friendly authoritarian European leader who closely aligns his country with Russia and China, these Western officials see Orban’s relationship with Dodik as one aspect of Hungary’s greater agenda that undermines transatlantic unity.

The 2024 U.S. Presidential Election: Stakes for Dodik

There is a perception among power brokers in Banja Luka that U.S. pressure on Republika Srpska would ease if Trump won the upcoming U.S. presidential election. These figures believe that a second Trump administration would conduct a foreign policy that would be more friendly to the interests of Moscow, Belgrade, and Serb communities in Serbia’s neighbors. Such assumptions about Trump help explain Dodik’s vow, which he made in December 2023, to push ahead with Republika Srpska’s official independence from BiH if the former American president returns to the Oval Office.

However, a Trump administration handling Serbian nationalism and Dodik’s anti-Dayton behavior any differently than the Biden-Harris administration is by no means inevitable. After all, during Trump’s first term, his administration did not lift any of the sanctions on Dodik that Obama’s administration imposed, and it is not clear why power brokers in Banja Luka should be convinced that a second Trump administration would necessarily do so.

Dodik has a record of lashing out at the current U.S. ambassador to BiH, Michael Murphy, who has strongly condemned the Bosnian-Serb leader’s anti-Dayton conduct.[36] If the U.S. appoints a different ambassador to Sarajevo, Dodik claims that Washington and Republika Srpska would have a better relationship. Yet, it is unclear if Trump would appoint a different U.S. ambassador to BiH, especially if it were to be seen as succumbing to a foreign leader’s demands. Additionally, tensions between the U.S. and Dodik would probably persist regardless of who serves as the American ambassador in Sarajevo. This is because the problems in Washington-Banja Luka relations are about the Daytonian equilibrium, the conflict in Ukraine, and other grander issues, which would not change in any significant way if Ambassador Murphy were replaced.

The Wider Geopolitical Picture

Regardless of who wins the 2024 U.S. presidential election and how, or if, Washington’s foreign policy shifts vis-à-vis Banja Luka, any changes in the U.S. approach to Dodik and his conduct in BiH would likely need to be understood within the context of Washington’s relationship with Belgrade. With Serbia being the dominant geopolitical and economic actor in the Western Balkans, U.S. administrations led by both Democrats and Republicans have assessed that Washington must work with Serbian President Alexander Vucic’s government to advance U.S. interests in this part of Europe.

The foreign policy establishment in Washington recognizes Serbia as the Western Balkan state with the leverage to stabilize the sub-region and rein in Belgrade- and Moscow-oriented Serbian nationalists such as Dodik. Therefore, as U.S. officials see it, engagement with Vucic’s government is required to prevent the Bosnian-Serb strongman from taking actions deemed threatening to U.S. and EU interests. There are many voices from Serbia’s neighbors who passionately disagree with this thinking and accuse the U.S. of naively “appeasing” a revisionist and revanchist government in Belgrade. But this is how the Biden-Harris administration has approached Serbia and the Biden-appointed U.S. ambassador to Belgrade, Christopher R. Hill, is probably the most pro-Serbia and pro-Vucic ambassador that Washington has ever had in Belgrade since Vucic’s Serbian Progressive Party came to power in 2012. The extent to which the Biden-Harris team has conducted such a Belgrade-friendly foreign policy has disappointed many non-Serb communities in the Western Balkans. In 2019/20, these non-Serb groups in BiH, Kosovo, and elsewhere in the sub-region were enthusiastic about Biden’s presidential campaign, expecting him to apply Washington’s pressure on Vucic’s government and be an advocate for Muslims in this part of Europe as Biden was during the 1990s as a U.S. Senator.

It is important to understand how Belgrade leverages instability in BiH and other Western Balkan countries to its advantage. Vucic can encourage Dodik and other Serb actors in this part of Europe to take certain actions that unsettle the West, then rein them in at the behest of Washington, London, and Brussels in ways that reinforce this image of Belgrade as a stabilizing and moderating force that the West needs.

The Russian-Ukrainian conflict has added to the value that the U.S. and, more broadly speaking, the West place on relations with Serbia. Mindful of how Belgrade challenges Moscow vis-à-vis the Ukraine conflict in certain ways (arming Kyiv, voting with the West on UN resolutions, comparing Russia’s conduct in the Donbas to NATO’s actions in Kosovo in the late 1990s, etc.), Washington and Brussels want to engage Vucic’s government enough to ensure that Serbia does not move toward alignment with the Kremlin in relation to the Ukraine war.

Another important variable in the equation is lithium in Serbia. Western European countries are determined to reduce their dependence on China for lithium, prompting EU members to become increasingly interested in securing this resource from Serbia.[37] The discovery of lithium in Jadar, a fertile valley in western Serbia, is perhaps the largest in Europe.[38] Germany, as the EU’s number one car maker, is particularly determined to excavate lithium in Serbia. In July 2024, Chancellor Olaf Scholz went to Belgrade for the signing of an EU-Serbia deal on “critical raw materials.”[39]

Serbian environmental activists warn of the Germans and other Europeans inflicting irreversible damage on their country’s environment without bringing benefits to the Serbian population at large. These are valid concerns mindful of how Serbia is already one of Europe’s most polluted countries and companies based in the EU have a record of taking advantage of Serbia’s looser environmental regulations.[40] Nonetheless, these Western governments having this interest in Serbia’s lithium will contribute to perceptions in the West that the Serbian leadership must be engaged and accommodated. This dynamic will enhance Belgrade’s geopolitical leverage at a time when the U.S. and its European allies seek to pull Serbia away from Russia and China while exploiting the landlocked European country’s natural resources.

In sum, when it comes to how Washington and other Western capitals approach Republika Srpska, there are many unknown variables in the equation to consider. However, it is reasonable to expect the U.S.—regardless of whether Donald Trump or Vice President Kamala Harris is at the helm—to deal with Banja Luka via Belgrade. This would mark a continuation of U.S. foreign policy in this part of Europe under both Democratic and Republican administrations. In the process, Vucic is set to further grow his clout by virtue of powerful countries from all geopolitical blocs assessing that engagement with Belgrade is essential to the advancement of their interests in the Western Balkans.

[1] “Who Is Threatening Peace in Bosnia?,” ISPI, April 11, 2022, https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/who-threatening-peace-bosnia-34564.

[2] “Serbs say they will pull their region out of Bosnia’s army, judiciary, tax system,” Reuters, October 9, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/serbs-say-they-will-pull-their-region-out-bosnias-army-judiciary-tax-system-2021-10-08/.

[3] Azem Kurtic, “Bosnia’s Serb Entity Passes Law Rejecting Constitutional Court’s Authority,” BalkanInsight, June 28, 2023, https://balkaninsight.com/2023/06/28/bosnias-serb-entity-passes-law-rejecting-constitutional-courts-authority/.

[4] “Dodik Signs Controversial Law Blocking Publication of Decisions By International Envoy to Bosnia,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, July 7, 2023, https://www.rferl.org/a/bosnia-dodik-signs-law-schmidt-decisions-high-representative/32493786.html.

[5] “Bosnia envoy revokes Bosnian Serb laws defying the state, peace deal,” Reuters, July 1, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/bosnia-envoy-revokes-bosnian-serb-laws-defying-state-peace-deal-2023-07-01/.

[6] “Bosnian Serb Dodik Says He’ll ‘Declare Independence’ If Trump Retakes U.S. Presidency,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, December 3, 2023, https://www.rferl.org/a/bosnia-dodik-declare-independence-trump/32712061.html.

[7] “Germany ends projects in Bosnia’s Serb republic over secessionist move,” Al Jazeera, August 9, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/8/9/germany-ends-projects-in-bosnias-serb-republic-over-secessionist-moves.

[8] “U.S. imposes sanctions on Bosnian Serb nationalist leader Dodik,” Reuters, January 18, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-sanctions-bosnia-dodik/u-s-imposessanctions-on-bosnian-serb-nationalist-leader-dodik-idUSKBN1512WI/.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Republika Srpska Official for Actively Obstructing The Dayton Accords,” July 17, 2017, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jl0708.

[12] Ibid.

[13] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Milorad Dodik and Associated Media Platform for Destabilizing and Corrupt Activity,” January 5, 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0549.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Targets Republika Srpska Officials for Activity Undermining the Dayton Peace Agreement,” March 13, 2024, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2175.

[17] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Targets Milorad Dodik’s Network of Wealth Generating Companies, Including Prointer,” June 18, 2024, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2414.

[18] “What is the impact of the US Sanctions on the Economy of Republika Srpska?,” Sarajevo Times, July 12, 2024, https://sarajevotimes.com/what-is-the-impact-of-the-us-sanctions-on-the-economy-of-republika-srpska/.

[19] “Bosnian Serb Entity Changes Banking Laws to Evade US Sanctions,” BalkanInsight, July 4, 2024, https://balkaninsight.com/2024/07/04/bosnian-serb-entity-changes-banking-laws-to-evade-us-sanctions/.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Council on Foreign Relations, “Russia’s Influence in the Balkans,” November 21, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/russias-influence-balkans.

[22] “USA: Russia secretly financed DF in Montenegro and Dodika in BiH,” VOA, September 13, 2022, https://www.glasamerike.net/a/rusija-tajno-finansiranje-dodik-bih-crna-gora/6745992.html.

[23] Council on Foreign Relations, “Russia’s Influence in the Balkans,” op. cit.

[24] “Russia already treating Bosnia’s Republika Srpska as an independent state,” Intellinews, April 25, 2024, https://www.intellinews.com/russia-already-treating-bosnia-s-republika-srpska-as-an-independent-state-322678/.

[25] Ibid.

[26] “Bosnian Serbs award Putin with medal of honor,” AP, January 8, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-putin-politics-government-milorad-dodik-7edc18d0133bbde4c5b84879c0dbe724.

[27] Ibid.

[28] “Bosnian Serbs Chase Closer Ties With Beijing Amid Western Pressure, Looming Debt,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, May 14, 2023, https://www.rferl.org/a/bosnia-serbs-china-debt-crisis/32411122.html.

[29] Ibid.

[30] European Council on Foreign Relations, “Mapping China’s Rise in the Western Balkans. Bosnia and Herzegovina,” https://ecfr.eu/special/china-balkans/bosnia-and-herzegovina/.

[31] “Hungary Throws Diplomatic Weight Behind Bosnian Serbs During Dodik Visit,” Reporting Democracy, May 15, 2024, https://balkaninsight.com/2024/05/15/hungary-throws-diplomatic-weight-behind-bosnian-serbs-during-dodik-visit/.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] “Orban Receives Award From EU-Sanctioned Bosnian Serb Separatist leader,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, April 5, 2024, https://www.rferl.org/a/bosnia-orban-award-visit-dodik-separatist-serb-eu-presidency/32892320.html.

[35] Adnan Cerimagic, “With Friends Like These: Orban’s Balkan Allies,” RUSI, March 15, 2024, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/friends-these-orbans-balkan-allies.

[36] “Dodik responds to US embassy’s accusations: Murphy represents those willing to kill,” N1, July 30, 2024, https://n1info.ba/english/news/dodik-responds-to-us-embassys-accusations-murphy-represents-those-willing-to-kill/.

[37] “Germany’s chancellor praises lithium deal with Serbia that could reduce Europe’s dependency on China,” AP, July 19, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/germany-serbia-lithium-scholz-vucic-114befbdab762c829b98616e94b99a0d.

[38] Ibid.

[39] “Thousands protest Serbia’s deal with the European Union to excavate lithium,” AP, July 30, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/serbia-protest-lithium-excavation-environment-175fd1eab486736b572b0ecbc8567783.

[40] Ibid.