In recent decades, Latin America has witnessed significant economic transformations, often marked by debt crises that have profoundly affected its economic and social stability. These crises, which occurred primarily in the late 20th century, exposed structural vulnerabilities within the region’s economies, such as dependency on commodity exports, high inflation rates, and substantial external financing. Facing growing budget deficits and an inability to meet their debt obligations, several Latin American countries found themselves in difficulty, necessitating international interventions to prevent more severe economic collapses.

In response to this situation, international financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank proposed structural adjustment programs for these crisis-hit economies. These programs aimed to stabilize public finances and restore growth by imposing substantial economic reforms. Frequently recommended measures included reducing public expenditures, currency devaluation, market liberalization, and privatization reforms. Although these interventions often brought temporary stability, they sparked intense controversy due to the substantial social costs involved, notably rising unemployment and reduced public services.

However, the actual impact of these programs on the debt levels of Latin American countries remains a topic of debate, leading to the main research question of this study: how have IMF and World Bank programs influenced the level of debt in Latin America?

To explore this question, this study proposes a three-part analysis. The first chapter, Debt in Latin America: A Review of Reality and Trends in the Last Ten Years, provides an overview of debt in key Latin American countries, examining prominent trends and characteristics over the past decade. This overview will help elucidate the current context and economic challenges facing the region.

The second chapter, Evaluation of the Effectiveness of IMF and World Bank Programs in Addressing Debt Challenges in Latin America: Case Studies of Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, assesses the effectiveness of the IMF and World Bank stabilization and structural reform programs.

Finally, the third chapter, Growth, Vulnerability, and Debt in Latin America: Future Trends and Challenges, examines the future outlook for Latin America by identifying potential dynamics of growth, economic vulnerability, and indebtedness.

Through an in-depth analysis of data and case studies, this research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the effects of IMF and World Bank programs on debt in Latin America and to guide future decisions for sustainable economic growth in the region.

1. Debt in Latin America: A Review of Reality and Trends in the Last Ten Years

1.1. Factors Influencing Debt Evolution in Latin America

International Interest Rates: Interest rates set by major world economies, particularly those of the United States, are important factors affecting debt in Latin America. An increase in international interest rates, often linked to decisions by the Federal Reserve, immediately raises the cost of dollar-denominated borrowings. Many countries in the region, such as Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico, hold substantial foreign-currency debt. Rising interest rates in developed economies put additional pressure on their public finances as the cost of debt servicing increases, thus reducing the governments’ capacity to fund development projects or invest in other economic sectors.

Commodity Price Volatility: Latin American economies are often sensitive to fluctuations in commodity prices, as many countries in the region heavily depend on exports of natural resources like oil, soybeans, gold, and copper. The ups and downs in commodity prices directly impact tax revenues and governments’ ability to repay their debt. For instance, when oil prices drop, countries like Venezuela and Ecuador experience a sharp decline in tax revenues, making debt repayment more challenging.

Domestic Fiscal Policies and Chronic Deficits: Chronic budget deficits are another major factor influencing debt in Latin America. Many countries in the region, notably Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico, have struggled to balance their budgets due to high public spending, inefficient subsidies, and a lack of fiscal discipline. These deficits are often financed through borrowing, leading to an accumulation of public debt over time. During periods of economic recession or slowdown, tax revenues decrease, further worsening the fiscal situation of these countries.

Inflation and Exchange Rates: High inflation and exchange rate fluctuations also play a crucial role in the evolution of debt in Latin America. In countries like Argentina and Venezuela, inflation has reached extremely high levels, leading to a depreciation of the local currency. This, in turn, has increased the cost of servicing dollar-denominated debt, worsening economic difficulties. Inefficient management of monetary policies and exchange rates has exacerbated the situation, making debt repayment more challenging and creating a vicious cycle of devaluation and inflation.

Mistakes Made by Latin American Countries

Argentina Argentina has made several major mistakes in managing its debt. It has accumulated substantial foreign-currency debt, particularly in dollars, increasing the pressure on debt servicing when global interest rates rise. The country has also maintained chronic budget deficits, financed through borrowing, without adequate fiscal reforms. Its heavy reliance on commodities, such as soybeans, has worsened the situation when prices fell, reducing tax revenues. Furthermore, high inflation and peso depreciation have further raised the cost of debt.

Brazil Brazil has faced similar issues with foreign currency-denominated debt, making it vulnerable to global interest rate hikes. Public spending management has been ineffective, with high subsidies and social spending lacking appropriate fiscal backing, resulting in recurrent budget deficits. As Brazil relies on commodity exports (particularly oil and soybeans), price drops have impacted its tax revenues. Additionally, high inflation has devalued the real, increasing the burden of external debt.

Chile Chile, although with a smaller proportion of its debt denominated in foreign currency, remains vulnerable to commodity price fluctuations, especially copper. The country has established stabilization funds, but its reliance on global prices has limited its flexibility in cases of price declines. Despite prudent fiscal management, Chile has sometimes underestimated external risks and has not always adjusted its fiscal policies proactively in response to global economic crises.

1.2 The Reality of Debt in Latin America

According to Brealey, Myers, and Allen,[1] debt can be defined as the total amount of financial obligations that an individual, a business, or a government owes to one or more creditors. In macroeconomics, public debt is often measured by the debt-to-GDP ratio, which assesses the debt burden relative to a country’s economic production capacity. However, this ratio is only one indicator among others for evaluating debt sustainability. It is also essential to consider the cost of debt servicing in relation to total public expenditures and the share of debt issued abroad. These factors are particularly significant for Latin America, where a large portion of the debt is issued in foreign currencies, making debt costs more sensitive to exchange rate fluctuations and inflation, unlike OECD countries, which benefit from lower interest rates and issue debt in local currency. As a result, debt servicing costs in OECD countries are generally lower, reducing pressure on public finances when exchange rates fall or inflation rises.

Debt can be a financing tool to stimulate investment and economic growth, but it carries risks if the debt level becomes challenging to manage, leading to solvency issues and high interest charges.[2]

In the macroeconomic context, a sustainable level of debt is crucial for financial stability, as excessive debt can limit a government’s or business’s ability to invest in new projects and respond to economic crises.

Debt in Latin America has significantly increased in recent years, influenced by multiple economic crises and global events, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic and rising global interest rates. Debt levels vary across the region, reflecting each country’s economic policies and specific contexts.

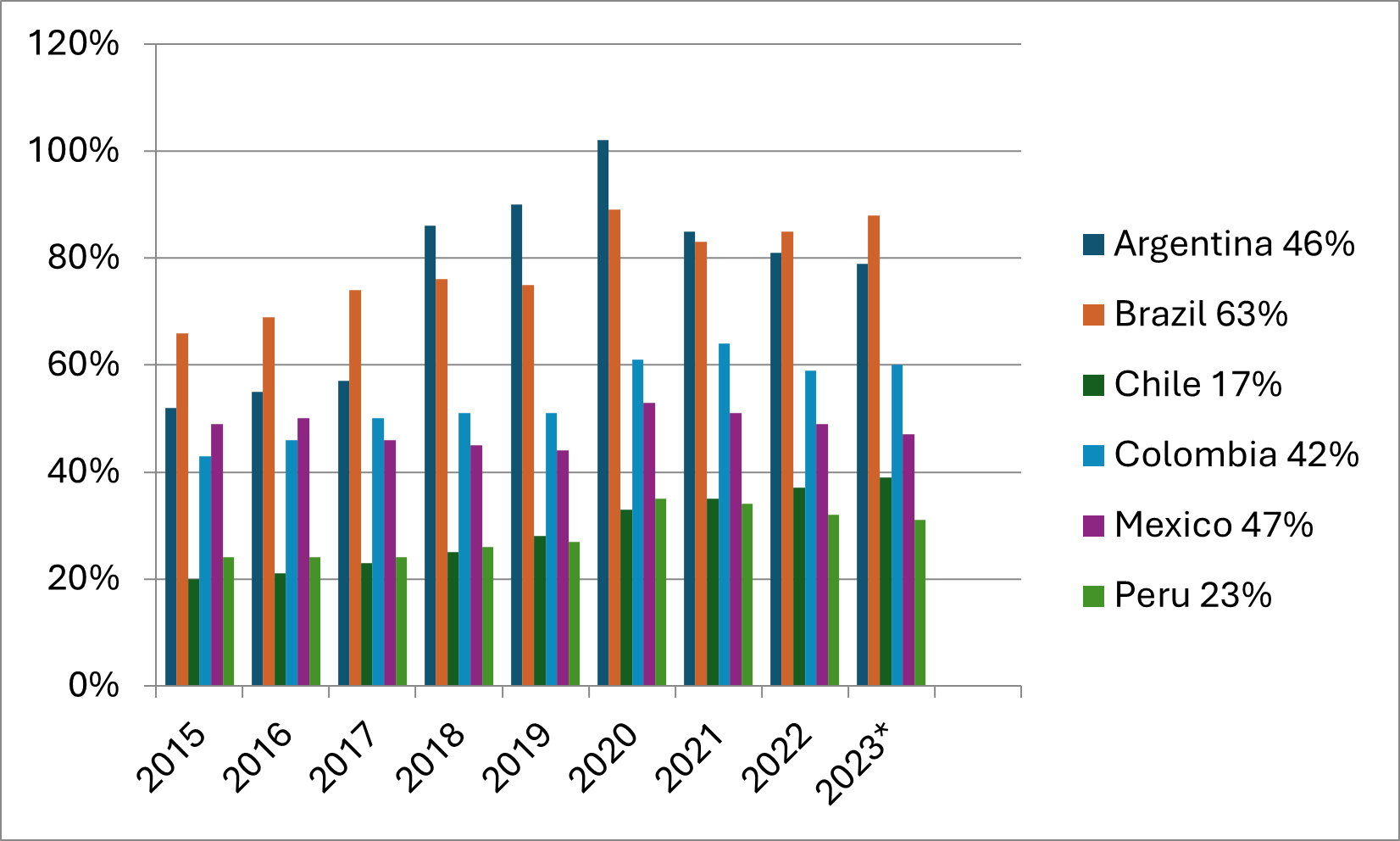

The analysis of debt ratios in Latin America between 2014 and 2023 reveals significant trends and marked disparities among the countries in the region. Overall, the period was characterized by a notable increase in debt-to-GDP ratios, particularly starting in 2018 and peaking in 2020, the year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Argentina, in particular, experienced a dramatic rise in its debt level, reaching an alarming ratio of 102% of its GDP, highlighting the ongoing economic crisis it faces. This situation results from a combination of poor economic management, past payment crises, and expansionary monetary policies. Although the ratio slightly decreased afterward, it remains high, signaling economic vulnerability.

Alongside Argentina, Brazil also saw its debt level climb, reaching 89% in 2020. This high level reflects a low economic growth rate and increased public spending. In contrast, countries like Chile and Peru displayed significantly lower debt ratios, partly due to more prudent fiscal management. Chile, for instance, managed to maintain substantial financial reserves, allowing it to withstand the crisis without reaching excessive debt levels. This contrast in debt management approaches underscores the importance of effective fiscal planning to support economic stability.[3]

The pandemic acted as a catalyst, exacerbating existing debt challenges. Governments in the region had to borrow heavily to fund social support programs, leading to increased debt levels. For example, Mexico’s debt ratio climbed to 53% in 2020, a significant increase compared to previous years. Despite forecasts of a slight improvement in debt ratios for 2023, the debt burden remains a concern. Governments must continue to implement structural reforms and improve tax revenue collection to ensure debt sustainability.[4] Balancing social funding needs with prudent debt management will be crucial for long-term economic stability in Latin America.

Graph 1: The evolution of the debt ratio

Source: World Bank

According to the graph of debt ratios in Latin America from 2014 to 2023, Argentina stands out as the most indebted country in the region. In 2020, its debt ratio reached an alarming level of 102% of GDP, a situation reflecting the repeated economic crises the country has faced over the past decades. Although this ratio slightly decreased afterward, reaching 79% in 2023, it remains alarming and illustrates the ongoing challenges Argentina faces in stabilizing its economy.[5]

In comparison, other countries in the region, like Brazil, also saw an increase in debt, reaching 88% in 2023. However, this figure remains lower than Argentina’s. Chile, on the other hand, has a debt ratio of 39%, while Colombia and Mexico show respective rates of 60% and 47%. Peru stands out with a debt ratio of only 31%. These figures demonstrate a significant variation in debt levels across the region, highlighting Argentina’s economic difficulties compared to its neighbors.[6]

Management, past payment crises, high amounts of debt issued in foreign currencies, and expansionary monetary policies have all contributed to worsening public debt. IMF and World Bank studies emphasize the need for structural reforms and improved tax revenue collection to ensure debt sustainability and support long-term economic growth (OECD, 2021). Issuing debt in foreign currencies increases vulnerability to exchange rate volatility, adding an additional layer of risk for emerging economies.

2. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of IMF and World Bank Programs in Addressing Debt Challenges in Latin America

2.1 Case Studies of Argentina

2.1.1 Debt History

- 2001 Debt Crisis

The Argentine economic crisis of 2001 remains a landmark case study of the challenges faced by emerging economies during periods of turmoil. This crisis resulted from a complex combination of ineffective economic policies, unsustainable debt, and fragile socio-economic conditions. In the early 1990s, Argentina implemented a convertibility policy, pegging the peso to the U.S. dollar, which, while initially effective in stabilizing inflation, quickly led to a loss of export competitiveness and debt accumulation. In 2001, amid a prolonged recession, the Argentine government sought assistance from the IMF, which imposed strict austerity measures, such as public spending cuts and tax increases, as part of a $40 billion aid package. These measures exacerbated social distress and sparked massive protests.[7] The situation culminated in a debt default, plunging the country into economic and social chaos.

Recent studies, such as those by Bottini and Sosa,[8] highlight the lessons to be learned from this crisis, emphasizing the need for more inclusive economic reforms and greater transparency in governance to prevent similar catastrophes in the future. Furthermore, the IMF report[9] analyzes how the policies adopted since then have not always addressed the fundamental needs of the population, illustrating the persistence of structural challenges in Argentina. Thus, the 2001 crisis represents not only a moment of economic failure but also a crucial opportunity to reflect on the interplay between economic policies, governance, and social welfare.

- 2018 Debt Crisis

The 2018 Argentine economic crisis exposed the persistent vulnerabilities of the national economy, exacerbated by controversial political decisions and underlying structural challenges. After a period of growth, the country experienced a rapid devaluation of its currency, the peso, amid runaway inflation that reached nearly 47% that year. This decline was triggered by a combination of factors, including poor economic management, growing budget deficits, and an excessive reliance on foreign financing.

The 2018 economic crisis considerably worsened Argentina’s debt situation, plunging the country into an even more pronounced state of vulnerability. Due to the rapid depreciation of the Argentine peso, foreign currency-denominated debt, primarily in U.S. dollars, became more difficult and costly to repay. Each decline in the peso’s value increased the weight of this debt, worsening the budget deficit and reducing the Argentine government’s financial capacity.

2.1.2 How Do the World Bank and IMF Intervene in Addressing Argentina’s Debt Challenges?

In response to the crisis, the Argentine government sought assistance from the IMF, resulting in a $50 billion financing agreement, the largest in the institution’s history.10 This agreement stipulated strict conditions, including austerity measures aimed at reducing the fiscal deficit, but these measures sparked criticism and protests due to their impact on social well-being. Recent analyses, such as those by Rojas,[10] highlight that the implemented reforms have often been perceived as favoring the interests of creditors over those of citizens, thus exacerbating inequalities. As a result, Argentina has continued to face significant economic challenges, including an increase in poverty and rising social tensions. This context underscores the importance of inclusive and sustainable economic policies to navigate future crises and promote equitable development.

The IMF and the World Bank play a crucial role in assisting countries like Argentina in addressing debt challenges. Each of these institutions is evaluated based on specific key performance indicators (KPIs). The IMF focuses primarily on short-term crisis management and aims to stabilize economies through rapid reform programs and short-term financing, with the goal to ‘reform and withdraw.’ The World Bank, on the other hand, emphasizes long-term economic development and institutional strengthening, with no mandate to provide financial support for immediate budgetary crises. This distinction in mandate and KPIs determines how each entity contributes to debt management and economic reforms. Their intervention often begins with direct financial support. The IMF provides conditional loans to meet immediate financing needs and stabilize foreign exchange reserves, as was the case with the $57 billion loan to Argentina in 2018.[11] These interventions are typically triggered by a sovereign default, followed by a restructuring process. For Argentina, this process was led by the Paris and London Clubs, which deal with middle-income countries that do not automatically benefit from debt reductions.

In addition to its financial support, the role of the IMF in these cases is to advise on appropriate restructuring and repayment schedules, which are negotiated and agreed upon by the debtor and lender. The IMF also offers bridging finance as an incentive to facilitate agreement on revised terms.

Argentina’s difficulty lies in its failure to fully execute its restructuring obligations. This issue stems from significant local lobbying by powerful groups, such as labor and business interests, which have blocked reforms and ousted reforming parties.

In the context of the absence of a common global framework for sovereign debt forgiveness for middle-income countries, it may be useful to highlight:

- The typical triggers for IMF intervention, such as currency or fiscal crises, often occur together.

- The sovereign debt negotiation processes under the Paris Club framework.

- The outcomes of these negotiations, particularly the restructuring of debt obligations coupled with reforms aimed at boosting growth to support repayment.

- The role of local interest groups in blocking necessary reforms.

These loans help restore market confidence and slow the depreciation of the currency, but they often come with conditions aimed at reducing the public deficit.

In parallel, the World Bank participates in debt restructuring processes, but its role is limited to negotiating flexible repayment terms. The Bank can help reduce interest rates as part of longer-term restructuring efforts, but it does not provide short-term financing to mitigate immediate shocks. This type of support is generally part of a Paris Club program, which is designed to address sovereign debt crises for middle-income countries.[12] According to Davoodi, Hamid R.,[13] to consolidate this financial assistance, the IMF also proposes macroeconomic stabilization programs that include measures to control inflation and reduce budget deficits. In Argentina, these measures have translated into restrictive monetary policies, such as increasing interest rates, aimed at stabilizing the currency. Recommendations also include cuts in public spending to improve the budgetary situation, which indirectly helps the country strengthen its capacity to repay its debt. However, this reduction in public spending must be well-balanced to avoid overly severe impacts on vulnerable populations.

Structural reforms are another important aspect of the World Bank and IMF intervention, as they aim to make growth more sustainable. The World Bank supports reforms such as the privatization of certain public enterprises and trade liberalization, which are designed to attract foreign investment and stimulate economic growth. It also encourages strengthening governance and transparency in public finance management. These reforms contribute to a more stable and predictable economic environment, reducing the risks of long-term financial crises.

To support the social effects of reforms and austerity, the IMF and the World Bank are increasingly focusing on maintaining essential social spending. According to an Oxfam analysis, 85% of the 107 loans granted by the IMF during the COVID-19 pandemic required or recommended austerity measures, illustrating the trend of prioritizing cuts in public spending even in times of crisis.[14]

Finally, the IMF and the World Bank provide ongoing monitoring and offer technical assistance to support countries in managing their debt and public finances. This monitoring helps anticipate and prevent economic crises through regular analyses and tailored recommendations.[15] Technical assistance also includes training to improve the skills of national financial institutions, strengthen banking supervision, and establish more effective fiscal policies. Through these coordinated interventions, the IMF and the World Bank aim to create a stable economic framework where debt gradually becomes more sustainable and where durable economic growth can take root.

2.1.3 The impact of World Bank and IMF programs on Argentina’s debt

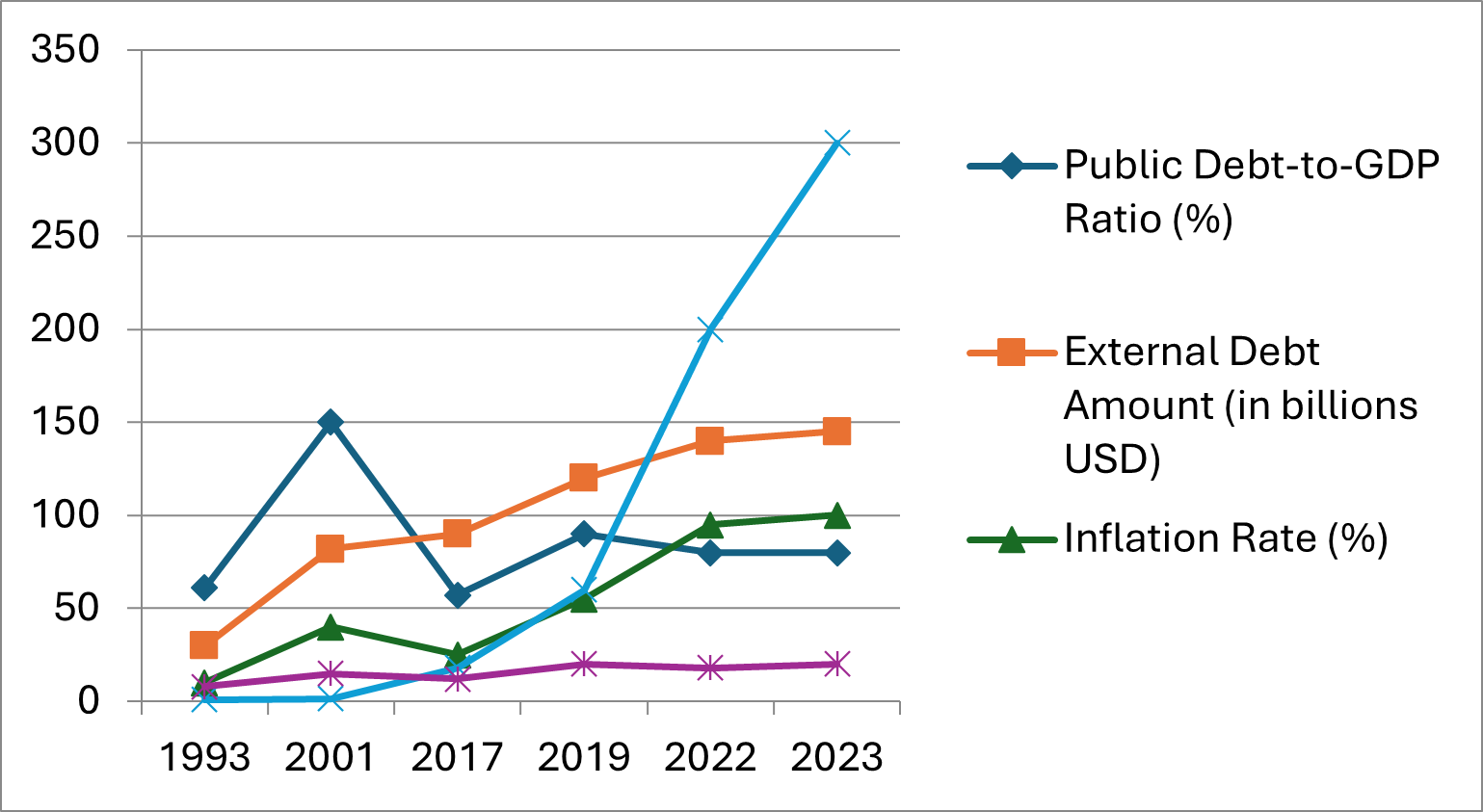

Graph 2: Evolution of Public Debt, Inflation, and Exchange Rate in Latin America (1993-2023)

Source: World Bank

In the 1990s, Argentina experienced an increase in its public debt, largely due to economic liberalization and convertibility reforms supported by the IMF. Indeed, debt rose from 61% of GDP in 1993 to about 150% in 2001. This rapid increase was fueled by external borrowing intended to support a fixed exchange rate regime, where the peso was pegged to the U.S. dollar. The 2001 crisis revealed the unsustainability of this debt, culminating in a historic default of nearly $82 billion, the largest ever recorded at that time.

In 2018, Argentina signed an agreement with the IMF, which represented a loan of $57 billion, the largest ever granted by the institution. Although this loan was seen as a temporary stabilization measure, it failed to achieve a sustainable reduction in public debt, which continued to rise, from 57% of GDP in 2017 to about 90% in 2019. This situation was primarily due to the devaluation of the peso and persistent budget deficits. Thus, this loan only covered the country’s immediate financial needs without providing a long-term solution to the debt problem.

Currently, Argentina’s public debt represents about 80% of GDP, an alarming proportion exacerbated by the fact that a large portion of it is denominated in foreign currencies. This situation makes the country particularly vulnerable to fluctuations in the peso and currency crises. In 2022, external debt accounted for approximately 45% of the total debt, thereby limiting the possibilities for effective debt reduction without compromising economic stability.

Furthermore, the share of interest payments in public spending has significantly increased due to rising indebtedness. For example, in 2019, these payments represented nearly 20% of the country’s tax revenues, which reduced public investment and economic recovery capacities. This dynamic contributes to a vicious cycle of debt, as debt servicing remains high even after renegotiations.

Finally, inflation, reaching around 100% in 2023, and the constant devaluation of the peso against the dollar have exacerbated the burden of foreign currency debt. The combination of currency devaluation and high inflation continues to weigh heavily on the debt, even with IMF support, creating an additional challenge for the country’s economic stability.

2.2. Case Studies of Brazil

2.2.1 Debt History

The debt crisis in Brazil, which erupted in the 1980s, marked a turning point in its economic history. Like several Latin American countries, Brazil had accumulated substantial external debt during the 1970s, borrowing heavily to finance development projects and infrastructure in the context of economic growth. However, the global economic situation radically changed at the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s. Interest rates in the United States surged dramatically, leading to a significant increase in the cost of debt for emerging countries like Brazil. At the same time, falling commodity prices reduced the country’s export revenues, further exacerbating the situation.

Starting in 1982, Brazil began to experience difficulties in making its repayments, resulting in a loss of confidence from international creditors. Faced with the impossibility of restructuring its debt without external assistance, Brazil had to negotiate with the IMF for financial support. The IMF then imposed rigorous structural adjustment programs on the country, requiring fiscal and monetary reforms aimed at restoring public account balance and reducing deficits. These programs included cuts to public spending, limitations on subsidies, and tax increases, measures that often resulted in reduced social services and higher unemployment.

Stabilization efforts intensified in the 1990s with the Real Plan, which allowed Brazil to regain some monetary stability and revive its economy. However, the debt crisis of the 1980s left scars that still influence the country’s economic policy today. This crisis revealed the structural vulnerabilities of the Brazilian economy, particularly its dependence on foreign capital and commodity exports. The lessons learned from this period have shaped how Brazil manages its debt and its relations with international financial institutions.

In summary, the debt crisis in Brazil represented a pivotal moment for the country’s economy. It forced the nation to reassess its economic priorities, diversify its funding sources, and strengthen its institutions to prevent a recurrence of such imbalances. This period also underscored the importance of prudent management of external debt and an economic policy capable of responding to external shocks more resiliently.

2.2.2 How do the World Bank and the IMF intervene in addressing Brazil’s debt challenges?

To help Brazil tackle its debt challenges, the World Bank and the IMF have implemented several initiatives that combine financing, economic reforms, and institutional support. In response to the economic crises of the 1990s and 2000s, the IMF provided emergency loans to stabilize Brazil’s economy, including a substantial $41.5 billion financial package in 1998. The purpose of this funding was to strengthen the country’s foreign exchange reserves, stabilize the real, and restore confidence in financial markets. In parallel, the World Bank[16] worked on rescheduling certain debts, allowing Brazil to postpone payments and reduce short-term debt pressure, thus giving the government more leeway to focus on economic reforms.

As part of macroeconomic stabilization programs, the IMF recommended measures to control inflation, which had reached 10% in Brazil in 2016, and reduce the budget deficit, which was then estimated at around 9% of GDP. These two key elements aimed to stabilize public finances and limit the rise in public debt, which accounted for nearly 75% of GDP that year. Following the measures adopted under these programs, Brazil managed to reduce its budget deficit to about 4% of GDP by 2019, and inflation was brought down to around 3.7% in 2019. Although public debt remains high, these adjustments have contributed to improving macroeconomic stability and bolstering investor confidence.

The World Bank encouraged Brazil to privatize certain state-owned companies, particularly in the energy and infrastructure sectors, leading to the privatization of more than 130 public enterprises between 1990 and 2020. At the same time, economic liberalization helped attract foreign direct investment (FDI), which increased from $50 billion in 2018 to nearly $70 billion in 2021, thereby diversifying revenue sources and fostering more sustainable economic growth. These reforms reduced the role of the state in certain sectors, contributing to an average GDP growth of 2.5% between 2017 and 2019 and a 15% increase in productivity in privatized sectors. As a result, Brazil strengthened its competitiveness, ranking among the leading emerging economies in global markets.

The World Bank also invested in social protection programs to mitigate the impact of austerity policies on the most vulnerable populations. The Bolsa Família program, which provides direct financial support to low-income families, is a major example of these efforts. In 2020, this program benefited nearly 14 million families, about 20% of Brazil’s population, with an annual budget of nearly $10 billion. Thanks to this support, extreme poverty was reduced by 15%, and household purchasing power increased, boosting domestic demand by an average of 2%. Additionally, the World Bank invested in social infrastructure, such as education and healthcare, contributing to an increase in school access for 98% of school-age children and improving basic health services. These initiatives have strengthened human capital, promoting inclusive growth and supporting social cohesion during periods of economic adjustment.

The World Bank and the IMF have provided ongoing technical assistance to strengthen Brazil’s economic institutions and improve public debt management.[17] Efforts have been made to enhance governance, transparency, and accountability in managing public funds, thus reducing corruption and improving public administration efficiency. This oversight has allowed Brazil to strengthen its financial management practices and consolidate the foundations of its economic resilience.

The interventions by the World Bank and the IMF have enabled Brazil to overcome major financial crises and reduce debt pressures, while also promoting structural reforms and strengthening social protection.[18] Through this combination of financial assistance, economic reforms, and institutional strengthening, Brazil has been able to stabilize its economy and build a solid foundation for sustainable growth.

2.2.3 The Impact of World Bank and IMF Programs on Brazilian Debt

The impact of World Bank and IMF programs on Brazilian debt has been substantial over recent decades, especially during periods marked by economic crises. Beginning in the 1980s, as Brazil faced high public and external debt, the IMF and the World Bank intervened to support the country through structural reform programs. These programs aimed to stabilize the economy, reduce budget deficits, and control inflation while encouraging reforms to promote long-term growth.

In the 1990s, important loan agreements, combined with fiscal austerity policies and economic liberalization, enabled Brazil to partially restore its solvency. Support from the World Bank and the IMF came in the form of structural adjustment programs designed to diversify the economy, privatize certain public industries, and attract foreign investment. These reforms helped reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio and stabilize Brazil’s economy, though often at social costs, with repercussions on employment and inequality.

However, in the early 2000s, Brazil again faced economic challenges, leading to a rise in public debt. In response, the IMF granted a $30 billion loan in 2002 to strengthen the country’s foreign reserves, stabilize the currency, and restore international investor confidence. This financial support helped Brazil weather the crisis and restructure its debt more sustainably. Subsequently, with rigorous fiscal and monetary policy management, Brazil even repaid its IMF debts ahead of schedule, demonstrating notable financial stabilization.

More recently, the impact of IMF and World Bank programs has been indirect. While Brazil continues to grapple with high public debt, representing around 80% of GDP in 2023, structural reforms supported by these organizations have helped strengthen economic foundations, promote better debt management, and encourage economic diversification policies. These interventions have fostered fiscal discipline, although significant challenges remain, particularly regarding social inequality and dependence on commodity exports.

2.3. Case Studies of Chile

2.3.1 How do the World Bank and the IMF address the debt challenges in Chile?

In the 1980s and 1990s, the World Bank supported Chile in its structural adjustment program, an initiative aimed at strengthening the foundations of the Chilean economy after the debt crisis. Among the measures adopted under these Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), several fiscal reforms were implemented. The World Bank advised on changes aimed at increasing tax revenues and making the tax system more efficient, which included reducing tax exemptions and improving tax collection.

Trade liberalization was also a key element of this program. Between 1990 and 2000, Chile reduced its average tariff rates from 40% to 10%, significantly opening up its markets. The country was encouraged to sign several trade agreements, notably with the United States, the European Union, and countries in the Asia-Pacific region. This liberalization allowed for a substantial increase in Chilean exports, which rose by 250% between 1990 and 2000, reaching nearly $30 billion in 2000. This growth in exports was essential for generating foreign currency, thereby stabilizing the debt and strengthening Chile’s economic position on the international stage.

Concurrently, labor market reforms were encouraged to create a more flexible environment capable of absorbing external economic shocks. The technical assistance and advice provided by the IMF and the World Bank played a crucial role in strengthening the country’s economic and financial institutions. These institutions shared their expertise in public finance management, monetary policy, and banking regulation, thereby enhancing Chile’s economic resilience in the face of debt challenges.

During periods of economic crisis, these organizations also proposed specific financing, such as conditional loans from the IMF. For example, in 1985, the IMF provided a $370 million loan to help Chile overcome a balance of payments deficit estimated at $1.5 billion. This financing was essential for rebalancing the country’s external accounts and stabilizing its economy. For its part, the World Bank provided long-term loans totaling approximately $2.5 billion between 1982 and 1994 for targeted development projects in strategic sectors.

In some cases, specific structural reforms were required in areas such as pensions, education, or energy. For instance, the pension system reform in 1981, which introduced an individual capitalization system, helped to increase labor productivity and boost state revenues. Through these reforms, Chile succeeded in reducing its dependence on debt, lowering the public debt-to-GDP ratio from 100% in the early 1980s to around 50% by the late 1990s.

2.3.2 The impact of World Bank and IMF programs on Chilean debt

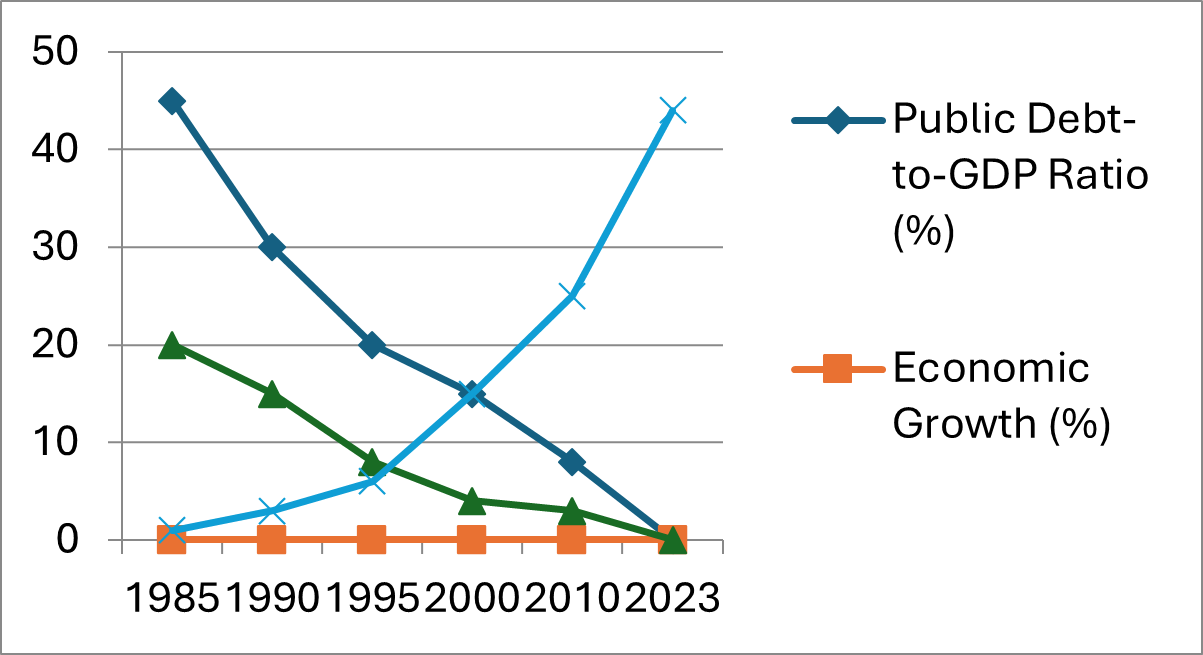

Graph 3: Evolution of Public Debt Ratio, Economic Growth, Inflation, and Foreign Exchange Reserves (1985-2023)

Source: World Bank

The interventions of the IMF and the World Bank played a crucial role in the economic stabilization of Chile, particularly in the 1980s, when the country faced high public debt, significant inflation, and low economic growth. Through stabilization programs and economic reforms, these institutions helped Chile improve its budget discipline, thereby limiting its reliance on borrowing. These efforts enabled the country to restructure its finances, reducing its vulnerability to global economic fluctuations and lowering the public debt ratio.

In the 1990s, Chile undertook major economic reforms focused on liberalization, diversification of exports, and reform of the financial sector. Accompanied by strengthened budget discipline, these reforms contributed to a significant reduction in public debt, which fell from 45% to about 15% of GDP by 2000. This change not only reduced the country’s dependence on external financing but also fostered a climate of confidence for investors, thus strengthening Chile’s economic position on the international stage.

The lasting impact of these reforms was particularly evident in 2010 when Chile reached a historically low level of public debt, accounting for only 8% of GDP. This achievement is directly linked to the policies supported by the IMF and the World Bank, which enabled the country to establish a solid foundation for long-term financial stability. By strengthening its budget management capacities, Chile became a model of fiscal discipline in Latin America, attracting the attention of other developing countries.

Despite a recent increase in public debt to 40.9% of GDP in 2023, primarily due to pandemic-related stimulus spending and other global economic challenges, Chile has demonstrated remarkable financial resilience. High foreign exchange reserves and the country’s ability to maintain moderate growth testify to the lasting effects of previous reforms. This indicates that the solid economic foundations laid through the interventions of the IMF and the World Bank continue to play a stabilizing role, even in times of crisis.

3. Growth, Vulnerability, and Debt in Latin America: Future Trends and Challenges

3.1. Factors Influencing Growth and Vulnerability in Latin America

Economically, GDP growth often depends on foreign investments, domestic consumption, and exports. Latin American households, particularly in large economies like Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina, play a central role in economic dynamism, and their consumption is supported by monetary and fiscal policy measures. The World Bank[19] noted that in some countries in the region, domestic demand accounts for over 60% of GDP, reinforcing the resilience of the economy against external fluctuations.

However, high levels of inflation can weaken this dynamic by eroding the purchasing power of households and leading to economic instability. Moreover, currency fluctuations have a significant impact: exchange rate volatility can disrupt foreign trade and compromise the economic stability of the region.[20] When local currencies depreciate sharply, the burden of external debt increases, which can undermine public finances and raise the risks of default. This dynamic is particularly sensitive for economies with high external debt, such as Argentina and Venezuela, where monetary fluctuations accentuate vulnerability to international financial markets.[21]

Political factors also play a crucial role. Enhanced political stability promotes the attraction of foreign investments, creating an environment conducive to growth. Conversely, political instability can deter investors and hinder economic development. Public policies, whether economic or social, also influence growth. Well-designed policies can reduce economic vulnerability, while inappropriate choices risk exacerbating imbalances.[22]

Socially, income inequalities exacerbate vulnerability. A high level of economic disparity can lead to social tensions and limit growth potential by hindering the inclusion of certain populations in development. Similarly, education and vocational training are crucial tools for improving productivity. Limited access to education increases vulnerability by rendering part of the population less capable of fully contributing to the economy.

In Latin America, unequal access to quality education poses a major obstacle to poverty reduction and improvement of living conditions. Marginalized populations, often from rural areas or disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds, have limited access to quality education, exacerbating their vulnerability. As UNESCO[23] indicates, “inequality of access to education prevents millions of young people from realizing their potential, harming not only their individual well-being but also that of the national economy.”

Environmental factors also affect the Latin American economy. Dependence on natural resources makes countries vulnerable to fluctuations in global prices, particularly for commodities. Furthermore, climate change presents increasing risks for sectors like agriculture, which remains vital in several economies in the region.

Finally, external factors, including trade relations and global economic crises, directly influence the economy of Latin America. Trade agreements and international cooperation can open up growth prospects, while global recessions or crises in other regions often have an immediate impact on Latin American economies, thus exacerbating their vulnerability.

3.2 Evolution of Growth Rates, Levels of Debt, and Economic Vulnerability in Latin America over the Past Decades

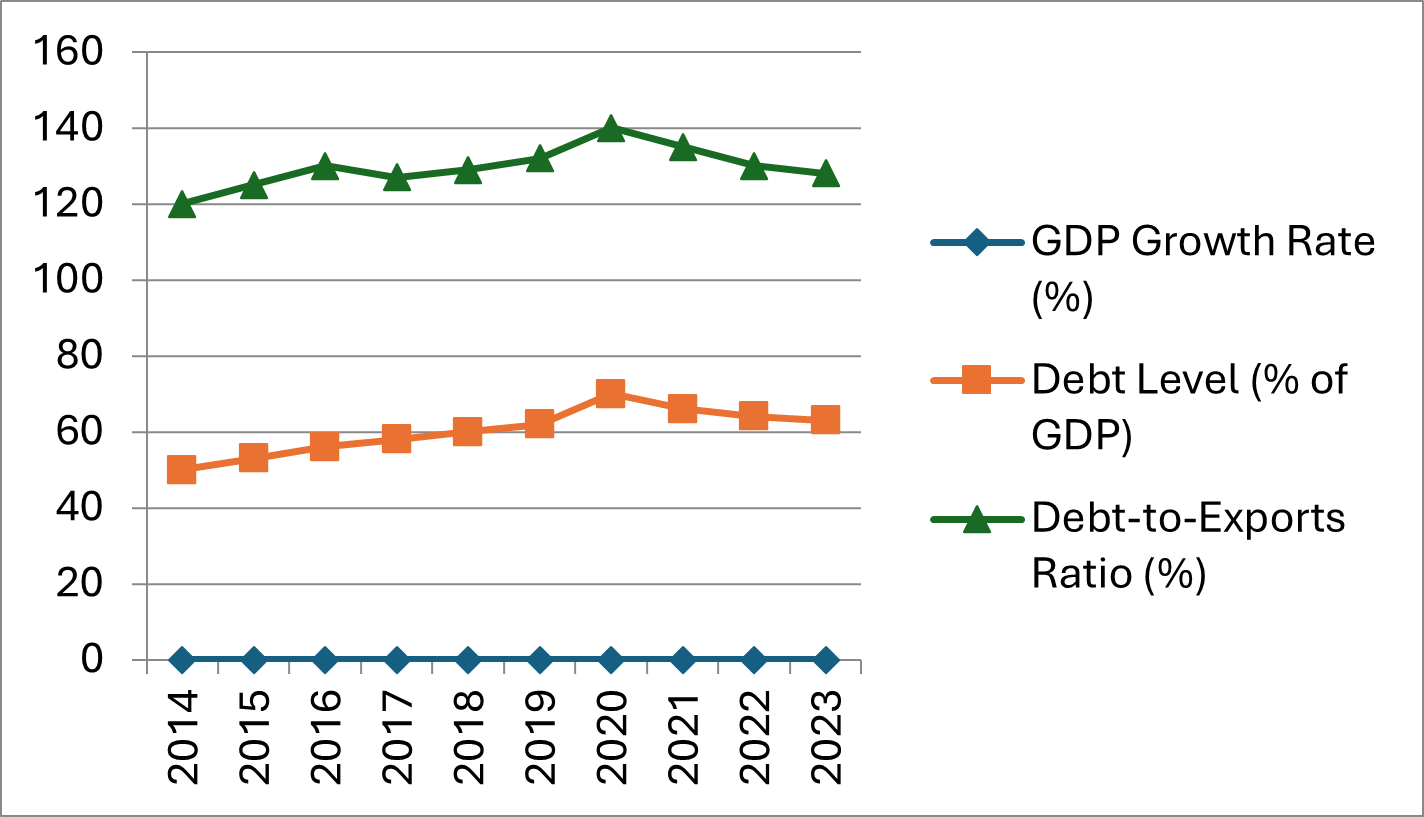

Graph 4: Evolution of GDP Growth Rate, Debt Level, and Debt-to-Exports Ratio (2014-2023)

Source: World Bank

The above chart highlights the dynamics between economic growth, debt levels, and economic vulnerability in Latin America over the past decade. GDP growth remained low and stable, with a notable decline in 2020, coinciding with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. To offset this decline, many countries increased their debt levels, which rose from 60% of GDP before 2020 to around 70% in that year. Similarly, the Debt/Exports ratio peaked around 2020 before gradually decreasing. This reflects an increased reliance on external financing during times of crisis, making these economies more vulnerable.[24]

The relationship between debt and economic vulnerability is also crucial. The debt-to-exports ratio, which reflects a country’s ability to meet its debt obligations through its export revenues, showed a continuous increase, reaching 140% in 2020. This indicates growing vulnerability, as countries found it increasingly difficult to generate sufficient revenue to manage their debt. However, a slight improvement was noted in 2021, with a reduction of this ratio to 135%, suggesting some economic recovery, although debt levels remain alarming.

It is important to clarify that this ratio refers specifically to the total debt compared to export revenues. Alternatively, some analysts might consider the foreign debt service costs in relation to total exports or foreign reserves, which can provide additional insight into a country’s ability to service its debt. Therefore, while the debt-to-exports ratio is a significant measure, examining the ratio of foreign debt service costs to exports or reserves can also be crucial for understanding a country’s financial stability.

This situation exposes countries to external shocks, limiting their ability to invest in sustainable growth initiatives and reducing their resilience to global economic fluctuations.[25]

Finally, in 2023, growth rates stabilized at around 2%. Although the debt-to-GDP ratio is 63%, which is considered low by global standards, the situation remains problematic due to high levels of foreign currency borrowings, elevated inflation, underdeveloped local capital markets, and the high cost of borrowing driven by poor sovereign ratings. These factors contribute to Latin America’s continued vulnerability. This combination exposes the region to risks associated with unstable global economic conditions, such as fluctuations in interest rates. The limited capacity to invest in sustainable development projects and the persistence of inflationary pressures indicate that Latin America’s economic resilience remains weak. It is crucial for the region to implement strategies that promote inclusive economic growth while prudently managing debt levels to avoid future crises.[26]

3.3 Assessing Future Perspectives

Latin America stands at a crucial crossroads where sustainable growth strategies and initiatives aimed at reducing economic vulnerability must be proactively implemented. Among the key strategies, the energy transition toward renewable energy sources represents a significant opportunity. Many countries in the region are starting to invest in sustainable energy solutions, such as solar, wind, and hydroelectric power. These initiatives aim not only to reduce dependence on fossil fuels but also to promote economic development that respects the environment. According to a report from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), this transition can also create jobs and stimulate innovation in green technology sectors.

At the same time, it is essential to promote innovation and digital technologies. Investments in these areas can help diversify Latin American economies and strengthen their productivity. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)[27] emphasizes that adopting digital policies and supporting innovation is crucial for enabling countries to adapt to new economic realities and improve competitiveness in global markets.

To address economic vulnerability, strengthening social safety nets is a priority. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for effective social protection programs to support the most vulnerable populations. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) indicates that robust protection systems can not only mitigate the effects of crises but also contribute to a faster and more inclusive economic recovery. Moreover, economic diversification is a key strategy for reducing dependence on vulnerable sectors, such as the extraction of raw materials. Encouraging alternative sectors, such as sustainable agriculture and tourism, can enhance the resilience of economies in the face of external shocks.

Finally, research into effective economic policies is critical. This includes analyzing progressive tax policies that could help reduce inequalities while financing necessary social programs. The World Bank has emphasized that well-designed tax policies can strengthen social cohesion and promote inclusive growth. Additionally, regional cooperation and economic integration are also promising avenues for research. Enhanced cooperation among Latin American countries can foster collective resilience against global challenges, particularly in trade and investment.

Conclusion

It is evident from examining the debt problems in Latin America over the past decade that the economic situation of the countries in the region has been marked by a complex and often worrisome evolution. A review of the reality and trends of indebtedness reveals a significant increase in debt levels, exacerbated by economic crises and fluctuations in international markets. These factors have highlighted the vulnerability of Latin American economies, illustrating an urgent need for structural reforms and prudent debt management.

The assessment of the effectiveness of IMF and World Bank programs, focusing on case studies from Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, shows that while these initiatives have provided crucial support, their results have been mixed. In some cases, the programs have facilitated beneficial reforms, while in others they have raised concerns about economic sovereignty and social impacts, sometimes exacerbating inequalities.

In light of these challenges, the interaction between economic growth, vulnerability, and debt remains at the forefront of concerns for the future. Countries must navigate an uncertain global environment, where rising international interest rates and economic pressures can jeopardize stability. Therefore, it is imperative that policymakers implement strategies that not only foster growth but also enhance economic resilience by strengthening institutions and improving governance to ensure effective debt management. If these reforms are not implemented, lenders are likely to impose them through a restructuring process, or debtors may be excluded from capital markets, forcing them to self-impose reforms due to the lack of alternatives, as seen in Argentina. This approach can have similarly negative impacts on social indicators.

[1] Brealey, Richard A., Stewart C. Myers, and Franklin Allen, Principles of Corporate Finance. 13th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2019).

[2] Cline, William R., International Debt Reexamined (Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics, 2004).

[3] Ghosh, Atish R., Jonathan D. Ostry, and Rodrigo A. Espinoza, “The Two Crises of the Argentine Economy,” IMF Working Papers, 2013.

[4] OECD, OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2021 Issue 2. (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2021).

[5] International Monetary Fund (IMF), Argentina: 2001–2021: Two Decades of Economic Turmoil (Washington, DC: IMF, 2021).

[6] OECD, Debt Transparency: A Primer for Low-Income Countries (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2021); IMF, 2021.

[7] Weisbrot, Mark, and Rebecca Ray, “Argentina: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” World Economic Review 8, no. 3 (2019): 23–40.

[8] Bottini, Natalio, and Susana Sosa, “The Political Economy of Economic Crises in Argentina: A Historical Perspective,” 2020.

[9] International Monetary Fund (IMF), Argentina: 2001–2021: Two Decades of Economic Turmoil (Washington, DC: IMF, 2021).

[10] Rojas, Carlos, “Crisis and Recovery in Argentina: Lessons from the 2001 Economic Collapse,” 2018.

[11] International Monetary Fund (IMF), “IMF Executive Board Approves US$50 Billion Stand-By Arrangement for Argentina,” Press release, 2018.

[12] World Bank, International Debt Report 2023 (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2023).

[13] Davoodi, Hamid R., Peter J. Montiel, and Anna Ter-Martirosyan, Macroeconomic Stability and Inclusive Growth (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2022).

[14] International Monetary Fund, IMF Lending During the Pandemic: Maintaining Social Protection Amid Fiscal Adjustment, (Washington D.C.: IMF, 2022).

[15] OECD, OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2021 Issue 2 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2021).

[16] World Bank, International Debt Report 2023 (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2023).

[17] World Bank, Brazil – Systematic Country Diagnostic: Pathways for Inclusive Growth (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2019).

[18] International Monetary Fund, Brazil: Selected Issues. IMF Country Report No. 19/200, International Monetary Fund, Washington D.C., 2019.

[19] World Bank, Global Economic Prospects: Resilience Amid Uncertainty (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2023).

[20] Reinhart, Carmen M., & Rogoff, Kenneth S., This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly (Princeton University Press, 2009).

[21] International Monetary Fund (IMF), Argentina: 2001–2021: Two Decades of Economic Turmoil (Washington, DC: IMF, 2021).

[22] Stiglitz, Joseph E., People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent (W.W. Norton & Company, 2019).

[23]UNESCO, Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education (Paris: UNESCO, 2021).

[24] World Bank, World Development Indicators 2024 (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2024).

[25] International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Economic Outlook: Global Financial Stability Report, 2024.

[26] Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPALC), Perspectives économiques pour l’Amérique latine 2024, 2024.

[27] OECD, Debt Transparency: A Primer for Low-Income Countries (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2021).