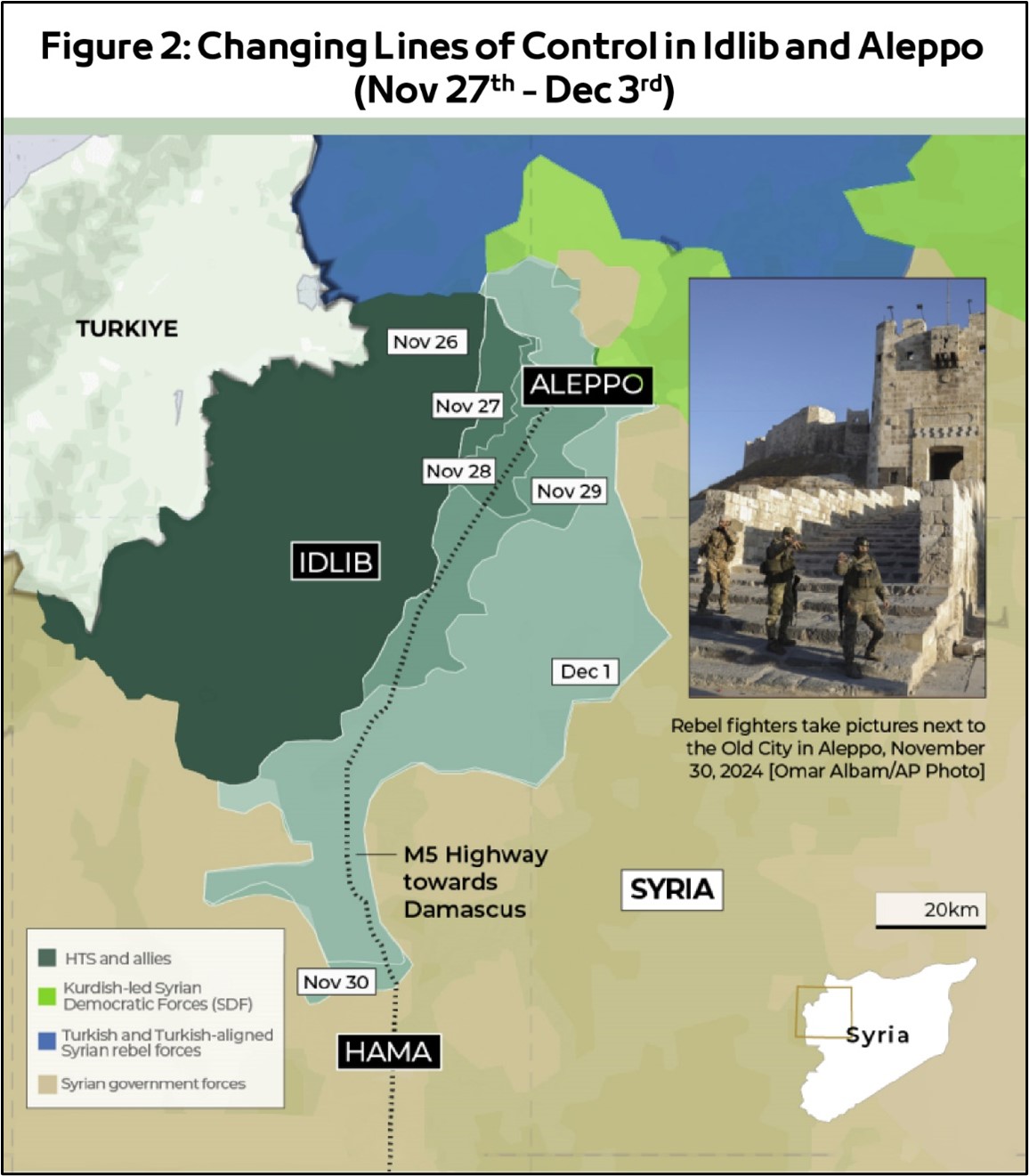

November 27, 2024, will almost certainly prove to be the most consequential day in the Syrian conflict since September 17, 2018, when lines of territorial control were consolidated following the Sochi Agreement between Russia and Turkey. This agreement established a demilitarized zone in Idlib, the last line of contestation to be stabilized in Syria at the time. Fast forward to November 27, 2024, and Hayyat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)—the militant group that has controlled most of Idlib governorate since 2017 (one of the last remaining zones outside of Syrian government control)—launched an offensive. Alongside militant groups Ahrar al-Sham, the National Liberation Front, Jaish al-Izza, and the Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement, HTS seized 19 towns and villages in eastern Idlib and western Aleppo governorates by evening.[1]

Source: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

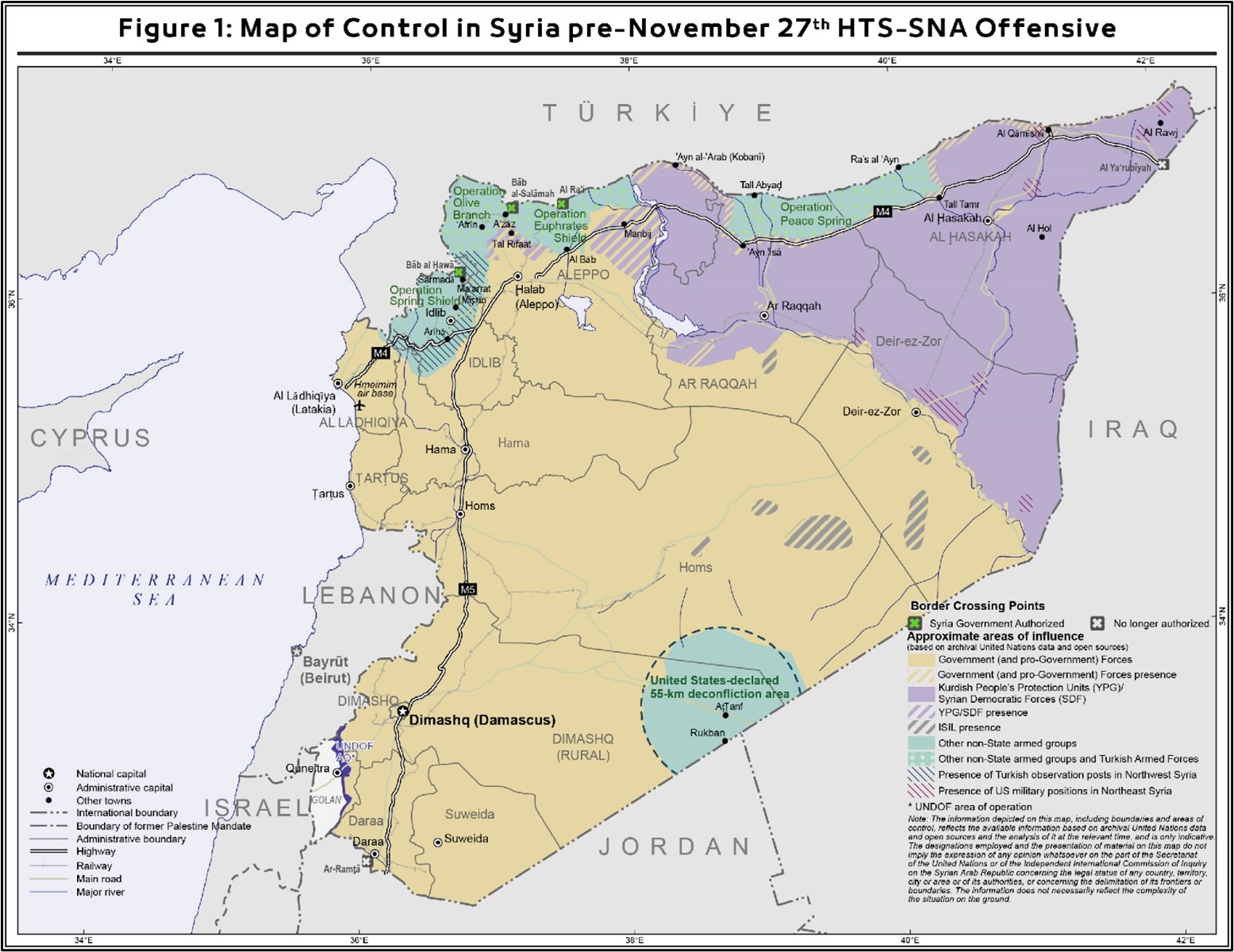

On November 28, Syrian government forces were expelled from the remainder of eastern Idlib, with the rebels advancing toward the highly strategic M5 Highway, which connects Syria’s north to Damascus in the south (shown in Figure 1). These advances continued through November 29, when the rebels entered the outskirts of Aleppo city—Syria’s second-largest city and traditional economic center. By November 30, Aleppo city had fallen to the rebels. They then turned south toward Hama, the next city along the M5 Highway toward Damascus, reaching within 20 kilometers of the city that same day.

Recapturing Aleppo is out of reach for the Syrian government, as it lacks the troop numbers necessary for such an operation.[2] Accordingly, the question is how far south will the rebels be able to advance before the government can mount a successful defense?

Source: Al-Jazeera

As of December 3, 2024, the time of writing of this piece, the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA), the military wing of the internationally recognized Syrian opposition, has joined forces with HTS and allied factions in the countryside near Hama city. This combined effort is encountering a Syrian government defensive line on the outskirts of Hama, a resistance absent during the earlier capture of Aleppo. While the pace of the advance has slowed, HTS and SNA forces continue to make progress toward Hama city.[3]

Source: Al-Jazeera

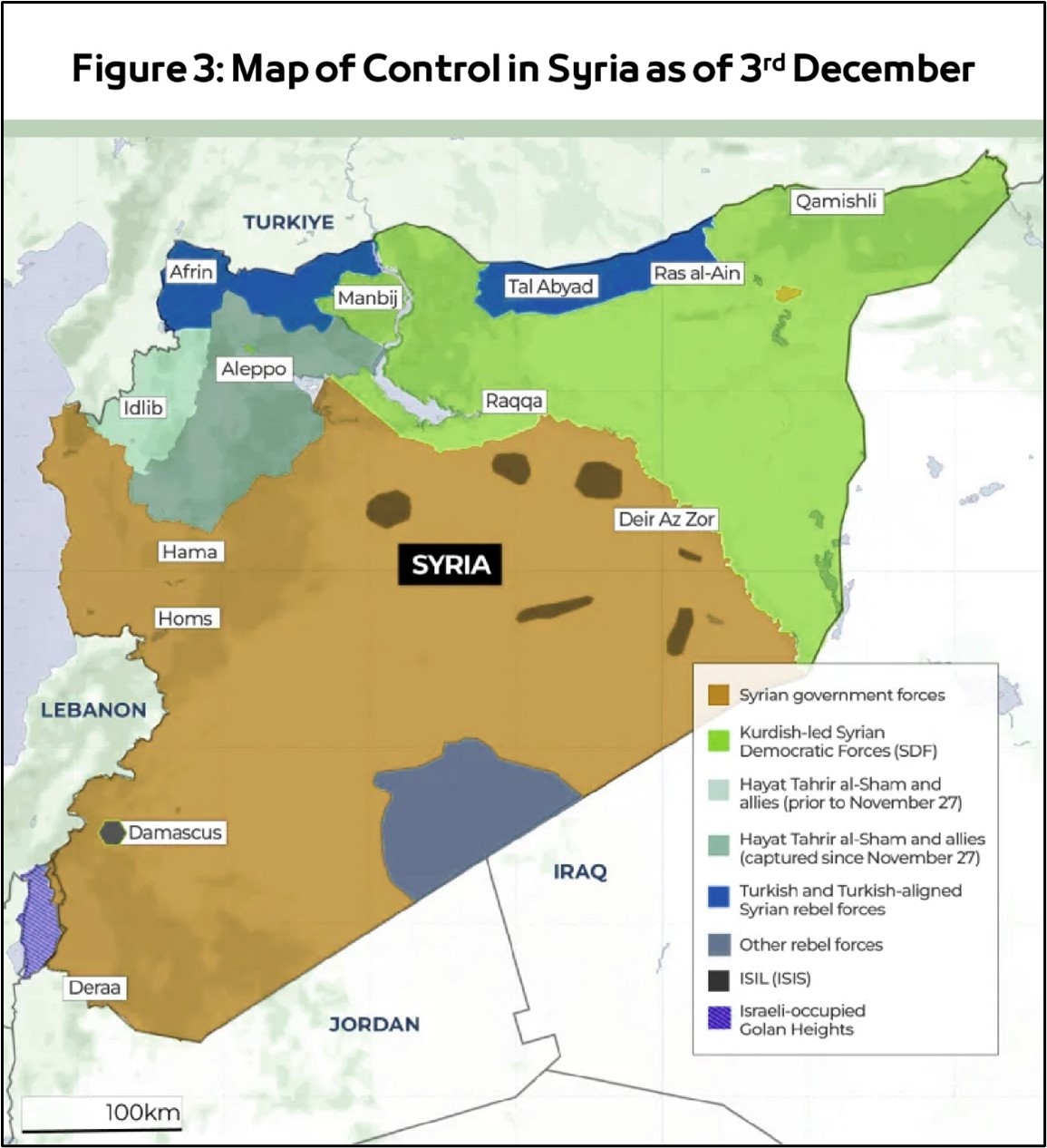

Adding to the gravity of the challenges facing the government, as of December 3, 2024, the Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—the military wing of the Autonomous Administration of Northeast Syria (AANES), which controls nearly all of Syria’s northeast (as shown in Figure 3)—had advanced beyond the pre-existing line of control into government-held territory in Deir-ez-Zor governorate, Syria’s oil heartland.[4] Here, the SDF has now seized control of seven villages and is engaged in clashes with the SNA – the SNA is a Turkey-backed umbrella organization, and Turkey has consistently resisted the SDF’s existence due to its ties with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a longstanding adversary of Turkey.

Meanwhile, Iranian-linked militias from Iraq entered Syria around December 2 to support the government.[5] However, these forces face logistical challenges in reaching western Syria due to the Israeli Air Force’s ongoing campaign of airstrikes targeting Iranian networks across Syria—a campaign that has intensified significantly over the past year. Notably, reports indicate that Hezbollah does not plan to re-enter Syria to aid the military (Hezbollah’s support was crucial in enabling the Syrian military to repel opposition forces during the mid-2010s).[6]

Clearly, the Syria of early December 2024 is fundamentally different from the Syria of late November. Given that, what does this new balance of power pose for the most salient, and dynamic, trends regarding international engagement with the Syria file that have defined and manifested throughout 2024. After analyzing the implications of the current rebel offensive for the Assad government’s continuity, the remainder of this piece will explore its broader effects on three key dynamics: the future of U.S. Syria policy, the Turkish-Syria rapprochement process (and, in connection, the future of Syria’s Kurds), and the trajectory of European Syria policy.

Section 1: Implications of the Ongoing Rebel Offensive for Assad’s Continuity

The Relative Power of the Government’s Forces Versus its Adversaries

The events of the past week conclusively show that the levels of Syrian military, Russian and Iranian power in Syria is quantitatively and qualitatively substantially less than it was in the post-Sochi Agreement era. Since Russian and Iranian intervention began in the Syrian Civil War in 2015, Assad has heavily relied on both for his survival.

However, since 2022, Russia has redirected much of its military assets—both personnel and equipment—to its conflict in Ukraine. Similarly, the Hezbollah-Israel conflict, which erupted in October 2023, has compelled Hezbollah to channel its resources back to Lebanon to support its war effort. Compounding these challenges, Iranian-linked militias and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) have faced significant disruptions to their supply chains stretching from Iraq through Syria to Lebanon due to intensified Israeli Air Force campaigns over the past year.

Aside from the significant decrease in the availability of military support from its partners, the Syrian military itself has been hemorrhaging capacity and capability over recent years due to systemic corruption, restructuring reforms, organizational mismanagement, and troop fatigue.[7] But this decline in Syrian military strength is compounded by the notable gains in the capability of HTS over the same period. Following significant defeats in 2020, HTS pursued a strategic overhaul, establishing a military academy, forming a centralized command structure that includes the militant group partners participating in the current offensive (thus greatly increasing the size of the coordinated force able to be deployed), developing an indigenous defense materiel industry, establishing notable drone capacity (key to urban warfare), and raising special forces units with reconnaissance and fire-directing capability.[8]

Outside of these improved ‘hard’ capabilities, HTS (and its now-coordinated partners) have, firstly, developed doctrinal robustness that improves civilian protection and focuses on demonstrating compassion to liberated communities; secondly, established strategic communications frameworks that emphasize shared anti-Assad objectives with these communities (as opposed to Islamist or jihadist aims); and thirdly, begun showing diplomatic pragmatism regarding publicized openness to dialogue with Russia.[9]

An Additional Challenge to Assad from the South?

A further key consideration is that the success of the HTS and SNA offensives in the northwest could inspire the year-long organized protest movement in Suweida governorate in the south to attempt something similar. The Suweida movement, which since August 2023 has been protesting government control and spiraling economic deterioration, has resulted in Suweida largely slipping out of the government’s control, with armed local factions taking charge of much of its governance.[10]

Daraa and Quneitra governorates, immediately to the west of Suweida along Syria’s southern border, have also de facto slipped from government control during this time. However, in addition to local armed factions, Iran-linked militias have occupied parts of this power vacuum in Daraa and Quneitra to pursue Iran’s goal of consolidating a drug-trafficking corridor along the border with Jordan.[11]

The unfolding changes to government territorial control in the northwest may well be seen as an opportunity by the armed local governing factions in Suweida, Daraa, and Quneitra, inspiring them to escalate and expand their resistance efforts. This could lead not only to increased conflict with the Syrian military along territorial lines of control but also to clashes within these territories, as Iran-linked militias already entrenched in the area may attempt to consolidate the territory for their own objectives.

Indeed, there are emerging signs that these southern factions are already moving in this direction. The remnants of Free Syrian Army factions in the south, which form the backbone of these de facto governing entities, announced a general mobilization in the past few days to exploit the opportunity created by Syrian military elements being redeployed from the south to the northwestern front to counter the HTS-SNA offensive.[12] If the Iran-linked militias fail to overcome this mobilization, the Syrian military may be forced to divide its already overstretched forces across both southern and northern fronts—a precarious situation for Assad.

Section 2: Future of US Syria Policy

What do the events of the past week pose for America’s ongoing involvement in Syria?

The Pre-November 27 US Calculus

At the start of 2024, the Biden Administration was reportedly already considering a full withdrawal of US troops from Syria.[13] Escalating hostilities—caused by the Gaza crisis—between Iran-linked militias and US forces in Syria and northeast Jordan were driving US discussions of an exit, primarily due to concerns that American troops in Syria could become embroiled in a wider conflict. However, with the Syrian government’s territorial control now being substantially undermined in the northwest and potentially soon in the south, is Trump’s calculus facing a fundamental change? Prior to November 2024, this calculus was likely as follows.

During his first presidency, Trump viewed the US presence in Syria as unnecessary, particularly after the Islamic State lost its territorial control. This perspective led him to order a US withdrawal in 2019 from a corridor along the Turkish border, where American troops had been stationed to protect the primarily Kurdish population.[14] While a full withdrawal from northeast Syria under Trump did not materialize as initially outlined, the US troop presence was nonetheless reduced from 2,000 to 900 during his presidency.

More broadly, the Trump Administration’s approach to Syria focused on transitioning all US military and financial support to the counter-Islamic State campaign, as opposed to previous efforts to support the Syrian political opposition. US support for United Nations Security Council Resolution 2254—which calls for a transitional governing body with full executive powers leading to free and fair elections in Syria—became largely rhetorical and superficial. This approach has remained the status quo during Trump’s absence from office.

Given Trump’s history and his well-publicized desire to disentangle the US from Middle Eastern conflicts and immediately “end all wars,” the dynamics influencing President Biden’s calculus regarding considering withdrawing US troop presence in Syria pointed toward an even greater likelihood of such a withdrawal under Trump.

In terms of Trump’s stance on ongoing Gulf-Assad normalization efforts—and the increasing moves toward normalization with Assad by multiple European states—Trump may well have progressed the US position from its current tacit acceptance to one of open endorsement. This shift in stance could align with a renewed “maximum pressure campaign” against Iran, a hallmark of Trump’s prior foreign policy. A Trump Administration might view normalization with the Assad government as a strategic lever to counter Iran, leveraging closer ties between Assad, the West, and the Gulf states to undermine Iran’s extensive strategic interests and assets in Syria.[15]

The Post-November 27 US Calculus

Does anything regarding the territorial changes over the past week change this calculus? Reports have emerged that the US engaged in discussions just days before the current rebel offensive began about the possibility of winding back sanctions on the Assad government if it cut off Iranian supply lines through Syria to Lebanon and expelled Iranian military influence from Syria.[16] However, regarding the US stance on such normalization of Assad, it seems likely that the American position will now be to wait and see how the dust settles from these ongoing changes to control in the country. Given the territorial advances of non-Iran-aligned factions (whether HTS or SNA in the northwest, or local armed elements in the southwest), it could eventuate that Iranian influence faces existential challenges without any need for US-Assad collaboration, thus negating the need for the US to support normalization.

In terms of a potential US troop withdrawal from eastern and northeastern Syria, it seems likely that Trump would only execute such a move if his administration was confident it would not lead to a resurgence of Islamic State in those territories. Such a resurgence would pose a greater political stain on Trump’s record than the continuation of US troop presence. Currently, preventing an Islamic State resurgence is an increasing challenge. Aside from the 10,000 Islamic State fighters held in SDF prisons and the 46,000 detainees linked to Islamic State in the Kurdish-administered Al Hol prison camp—both of which are under-resourced and tenuously secured[17]—Islamic State activity across Syria, particularly in the east, has been rising over the past year.[18]

If ongoing challenges to Syrian government control divert its forces away from the line of demarcation with the SDF in the northeast to address threats in the northwest and southwest—leaving the SDF largely on its own to prevent ISIS resurgence in Deir-ez-Zor governorate (currently the epicenter of Islamic State activity)—then an Islamic State resurgence would be highly likely without continued US military support of the SDF. This scenario would make a Trump-ordered US withdrawal less likely. However, if a deal were struck with Turkey to fill the gap left by a US exit and take sufficient control of the northeast, then a US exit could be conceivable. Achieving such a deal, however, without triggering widespread Turkish-SDF conflict in the northeast—a self-defeating outcome in terms of stabilizing the region against Islamic State—would be a very tall order.

Section 3: Turkey-Syria Rapprochement and the Syrian Kurds

What do the past week’s developments pose for the prospects of the nascent Turkey-Syria rapprochement process?

The Pre-November 27 Rapprochement Progress

After severing diplomatic ties with Syria in 2012, Turkey began signaling an interest in rebuilding relations in 2022.[19] This rapprochement process appeared nearly dead in 2023[20] but started gaining momentum throughout 2024. Turkey’s apparent desire for normalization seemed driven by efforts to ensure that the Assad would refrain from actions further destabilizing the border with Turkey, destabilization that would trigger additional Syrian refugee flows into Turkey—a serious concern given the long-struggling Turkish economy, which was seen as unable to absorb further inflows.

Syrian military actions in Idlib from late 2023 through 2024 were of particular concern to Turkey in this context. Additionally, increasing efforts by the AANES to push toward quasi-statehood throughout 2024 likely influenced Turkish moves toward rapprochement.[21] Ankara may have sought collaboration with Assad to prevent the realization of Kurdish statehood, which Turkey perceives as a significant security threat.[22]

Until the developments of the past week, 2024 had seen several significant advancements in the apparent rapprochement effort between Turkey and Syria. For instance, a first-of-its-kind meeting between Syrian and Turkish military delegations took place at Hmeimim air base in Syria in June, aiming to establish a level of mutual understanding regarding the volatile situation in Idlib. This meeting resulted in agreements for future discussions in Baghdad.[23] Around the same time, Iraq assumed a leadership role in a concerted mediation process between the two sides, achieving initial progress in softening their respective stances on how they were conceiving of the conditions for a prospective Turkish military withdrawal from northern Syria.[24]

Throughout the nascent rapprochement process over these months, Turkey has consistently expressed a willingness to work with Assad to develop a roadmap for reestablishing relations while nonetheless simultaneously publicly reassuring the SNA of continued Turkish support.[25] Turkey’s position has centered on a readiness to withdraw its military presence from the north if Assad genuinely engages in a political process with the opposition to ensure stability in the region. Assad, in turn, has maintained openness to talks but has emphasized that no bilateral normalization or engagement with the opposition, will be realized before Turkey withdraws from northern Syria and ends its support for Syrian opposition groups.

Implications of the Ongoing Offensive for the Rapprochement

The Turkish green-lighting of the SNA’s role in the ongoing offensive has upended any progress in the rapprochement process with Assad. Turkey’s support of the offensive appears to reflect one of two possibilities: either Ankara has lost hope in genuinely advancing normalization with Assad, or it was using the façade of rapprochement for domestic political purposes (presenting an image to the Turkish public that the Erdogan government was actively seeking a solution to the Syrian refugee problem). In either case, Turkey seized the far more attractive opportunity to favorably shift the balance of power in Syria when the chance arose this past week.

Any future Turkey-Syria normalization now faces a fundamentally altered reality. While the rapprochement had been at an apparent impasse until the past week, Turkey, by virtue of the SNA’s territorial gains, is poised to gain significantly greater leverage, regardless of whether the offensive advances as far as Damascus. Consequently, Assad’s previous intransigence regarding negotiations with the Turkish-backed opposition in the north may be forced to soften. Such a rapprochement would likely pose an existential challenge to Kurdish self-administration in the northeast, as Turkish-Syrian coordination vis-à-vis the Kurds would likely prove overwhelming.

The Future of Kurdish Designs for Statehood in the Northeast

Indeed, what do the past week’s developments more broadly mean for the Kurdish future in the northeast? Two key trends that have emerged over 2024 warrant particular focus: first, Kurdish moves toward holding elections in their self-administered territory, and second, emerging signs of nascent Turkish-Iraqi-Syrian coordination triangle aimed at subduing Kurdish strength in the northeast.

Regarding Kurdish elections, the AANES initially planned to hold first-of-its-kind municipal elections across its territory in June. However, these elections were postponed due to US pressure over the insufficiently democratic nature of the election conditions and Turkish warnings that such elections would provoke Turkish military intervention.[26] Despite the SDF-aligned High Electoral Commission in northeastern Syria authorizing elections to be held on a provincial basis in September—thus allowing each governorate to conduct elections on its own timeline, seemingly as an effort to bypass AANES acquiescence to US opposition—the elections have still not been held.[27]

The expansion of Turkey-backed SNA control over territory in northwest Syria during the past week—including the expulsion of Kurds from areas they controlled in Tal Rifaat and Aleppo, and clashes with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) along the pre-existing line of control west of Manbij, as shown in Figure 3 above[28]—is likely to further delay the AANES’ plans to hold elections and advance the institutionalization of emerging Kurdish statehood in the northeast. Given that Turkey’s normalization with Syria appears increasingly unlikely due to its support, tacit or otherwise, of the SNA’s seizure of government territory in the northwest, Turkey is now even less inclined to show restraint regarding military intervention in AANES territory. While such intervention would have further undermined the nascent rapprochement, that rapprochement is no longer a significant consideration (at least to a relevant extent).

The Kurdish Future in the Northeast vis-à-vis Previously Emerging Syrian-Iraqi-Turkish Cooperation

In terms of the emerging signs of a potential Syrian-Iraqi-Turkish cooperation triangle, the mediation of the Turkey-Syria rapprochement process by Iraqi Prime Minister Al-Sudani during the middle months of this year was accompanied by a concerted diplomatic effort by Iraq and Syria to regenerate security cooperation over their shared border region—a porous area plagued by cross-border smuggling and militant activity.[29] An implicit aim of this cooperation was likely to undermine Kurdish influence in the northeast.

Iraq’s interest in this aim stems largely from its ambitions to construct the vast Development Road project, an infrastructure and logistics corridor running from Al Faw on Iraq’s southern coast up to its northern border with Turkey—directly adjacent to Kurdish-controlled territory in northeast Syria. The cross-border movement of the PKK (the more extreme of the Kurdish militant factions) and their activities on both sides of the Iraq-Syria border are seen by Baghdad as threats to the Development Road’s success and to Iraqi security more broadly. This concern underpins Iraq’s interest in collaborating with Syria to increase security influence in northeast Syria.[30]

Turkey’s interests in the Development Road and in eliminating PKK presence from northeastern Syria and northern Iraq are similar. Turkey has pursued military operations and maintained a military occupation in northern Iraq for decades to achieve this goal. The concurrent timing of Iraqi mediation in the Syria-Turkey rapprochement effort and the push to deepen Syria-Iraq security coordination in eastern and northeastern Syria is, therefore, no coincidence.

The recent rebel advances in northwest Syria have cast significant doubt on the potential for such a Turkey-Iraq-Syria cooperation triangle however. With the Syrian military compelled to concentrate its resources on countering these insurgent movements to protect Damascus, it is unlikely to allocate sufficient forces to the east and northeast regions. This shift hampers the government’s ability to collaborate with Iraq in addressing issues such as border security and Kurdish influence. For the AANES, this development is advantageous, as the formation of some level of a Turkey-Iraq-Syria triangle would have posed a substantial threat to Kurdish authority in the northeast.

Section 4: Future of European Syria Policy

Pre-November 27 European Moves Towards Assad Cooperation

Over the past year, the Syria policy of many European states has reached an inflection point, as domestic economic and social pressures have seen them come to the conclusion that Syrian refugee flows are no longer tolerable, and that engaging with Assad has become a pragmatic necessity. This shift has been reflected in several key developments.

In May, after Lebanese officials threatened to stop intercepting boats carrying mostly Syrian refugees destined for Europe unless Beirut received more economic support from the EU, the EU announced a €1 billion aid package to Lebanon. This funding was intended to help prevent Syrian refugees from departing for Europe and to address the refugee crisis within Lebanon’s borders.[31] The EU made this deal knowing that Lebanon was increasingly cracking down on its Syrian refugee population, with forced deportations to Syria becoming more frequent—a trend that has persisted since this de facto green light from the EU.[32]

Later in May, an EU spokesperson remarked, “Syria is no longer among the priorities of the supporting (European) countries,” signaling that European efforts to push for a political solution to the Syrian crisis had waned significantly and the focus had shifted to reducing Europe’s exposure to the crisis.[33] Indeed, in July, a coalition of eight nations—Italy, Austria, Portugal, Slovenia, Greece, Croatia, the Czech Republic, and Cyprus—officially petitioned EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Josep Borrell to amend the EU’s sanctions-based approach against the Syrian government. The bloc advocated for establishing a level of engagement with Assad to facilitate refugee returns and shift the country from dependence on humanitarian aid to self-reliance.[34] That same month, Italy re-established its diplomatic presence in Syria by appointing a new ambassador to Damascus, raising the number of EU-member embassies in Syria to seven.[35] These efforts of the bloc culminated in September with the establishment of an EU working group tasked with revisiting EU policy towards Syria, particularly focusing on how to approach reducing sanctions and reopening more embassies in Damascus.[36]

Changes to This European Realpolitik?

What do the events of the past week mean for Europe’s trajectory? Much will depend on the emergent status quo once the dust settles. If the northwest of Syria is fundamentally reshaped with the SNA establishing control over a territory that stretches sufficiently deep into the country, and if the Syrian security apparatus emerges from this episode visibly unable to challenge this new territorial status quo, European sentiments regarding refugee returns may well be further heightened. In such a scenario, European countries may well argue that the newly shaped northwest represents a sufficiently safe territory for refugee returnees.

And what about European trends toward normalization with the Assad government? Up until the past week, Assad held the upper hand in terms of leverage vis-à-vis the international community (excluding Iran, Russia, and Turkey). Countries without a military presence in Syria (and even the US, despite its small military presence in the east and northeast) lacked the tools to compel Assad to the negotiating table for a political process. Over the past four years—since Rami Makhlouf’s challenge to Assad’s economic predominance in 2019—Assad has strategically restructured Syria’s economic networks by creating opaque business fronts directly under his control. These fronts have enabled him to centralize economic power, bypass sanctions, take over assets from potential rivals, and secure revenue streams directly into his personal coffers.[37] In other words, Assad has been able to withstand the insufficiently designed and ill-directed sanctions regime that has constituted the entirety of Western efforts to push him into accepting a political process.

However, now that the Syrian government could be facing an existential challenge, and given indications that Russia is using this challenge to push Assad to accept a political process—reports suggest that Russia is calibrating its support to ensure that, while Assad won’t fall, the territorial losses incurred will force him to the negotiating table with the opposition[38]—the tables may be turning. Depending on the new status quo that emerges following this offensive, European governments may feel inclined to slow the pace of their reengagement with Assad and the lifting of sanctions seeing as Assad may now be forced to compromise in ways he has been able to reject over the past decade.

Conclusion

The balance of power in Syria is shifting drastically. The ongoing HTS-SNA offensive has starkly exposed the structural weaknesses of the Syrian military, with systemic corruption, organizational mismanagement, and prolonged troop fatigue being compounded by the concurrent rise of HTS and its aligned partners. This coalition has demonstrated increasing operational effectiveness, further highlighting the fragility of the post-Sochi Agreement power structures. Developments in regions like Suweida, Daraa, and Quneitra could inspire local armed factions to escalate their own resistance efforts.

In terms of US Syria policy, the offensive’s impact has introduced new considerations. While reports indicated the US was exploring sanctions relief for the Syrian government prior to the outbreak of the offensive, the ongoing changes in territorial control that potentially undermine Iranian influence in Syria mean the US may find less need to revisit its sanctions policy. As for the possibility of a rumored US troop withdrawal from eastern and northeastern Syria, this will likely remain contingent on first ensuring that an Islamic State resurgence in the territory would not occur as a result of the exit.

The Turkish-backed SNA offensive has effectively torpedoed any nascent Syria-Turkey rapprochement while simultaneously expanding Turkey’s leverage. This development has significant implications for the AANES, whose electoral and territorial aspirations now face heightened uncertainty due to Turkey’s increased latitude to pursue its long-standing aim of taking decisive action against the SDF in the northeast. Conversely, the potential formation of an emerging Turkey-Iraq-Syria coordination triangle—what would’ve been a looming threat to Kurdish autonomy—now appears significantly diminished.

European approaches to Syria could also undergo notable changes. The potential establishment of a relatively (emphasis on relatively) stable rebel-controlled territory may increase European efforts to facilitate refugee return processes. Furthermore, the shifting balance of power as a result of the offensive may compel the Assad into political compromises it has long resisted, prompting European governments to reconsider their trajectory toward normalization and sanctions relief.

To underscore, Syria’s political landscape is now in significant flux: local armed factions, regional powers, and international stakeholders are recalibrating their strategies. The Syria of 2025 is set to be fundamentally different from the Syria of 2024.

[1] Al Jazeera Labs, “Mapping Who Controls What in Syria,” Al Jazeera, December 1, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/12/1/who-controls-what-in-syria-in-maps.

[2] Elijah Magnier, “Aleppo Is Reeling: Turkey’s Strategy and the Axis of Resistance Under Pressure,” EJMagnier.com, November 30, 2024, https://ejmagnier.com/2024/11/30/aleppo-is-reeling-turkeys-strategy-and-the-axis-of-resistance-under-pressure/.

[3] Al Arabiya, “Syrian Opposition Advances Close to Hama, Piling Pressure on al-Assad and His Allies,” Al Arabiya, December 3, 2024, https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2024/12/03/armed-opposition-forces-battle-syria-troops-near-key-city-of-hama-monitor; The New Arab, “Syria Rebels Approach Hama City Seizing 20 Towns and Villages, as Kurdish Forces Attack Regime in East,” The New Arab, December 3, 2024, https://www.newarab.com/news/syria-rebels-approach-hama-city-kurdish-forces-attack-regime; North Press Agency, “Government Warplanes Strike as SNA Factions Push Deeper Into Hama,” North Press Agency, December 1, 2024, https://npasyria.com/en/118885/.

[4] The New Arab, “Syria Rebels Approach Hama City Seizing 20 Towns and Villages, as Kurdish Forces Attack Regime in East,” The New Arab, December 3, 2024, https://www.newarab.com/news/syria-rebels-approach-hama-city-kurdish-forces-attack-regime.

[5] Suleiman Al-Khalidi and Maya Gebeily, “Iraqi Fighters Head to Syria to Battle Rebels but Lebanon’s Hezbollah Stays Out, Sources Say,” Reuters, December 3, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/iraqi-militias-enter-syria-reinforce-government-forces-military-sources-say-2024-12-02/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Philippe Droz-Vincent, “Syria: Coup Politics, Authoritarian Regimes, and Savage War,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, February 23, 2021, https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-1857.

Pierre Boussel, “The Stakes of Military Reform in Syria,” Manara Magazine, November 28, 2024, https://manaramagazine.org/2024/11/the-stakes-of-military-reform-in-syria/; Isaac Chotiner, “How the Syrian Opposition Shocked the Assad Regime,” The New Yorker, December 3, 2024, https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/how-the-syrian-opposition-shocked-the-assad-regime.

[8] Interview with a Syrian analyst who must remain anonymous due to the sensitive nature of his work providing security advice to NGOs on the ground in Syria.

[9] Ibid.

[10] The Syrian Observer, “Who Rules Southern Syria?,” The Syrian Observer, November 6, 2024, https://syrianobserver.com/foreign-actors/who-rules-southern-syria.html.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Interview with a Syrian analyst who must remain anonymous due to the sensitive nature of his work providing security advice to NGOs on the ground in Syria.

[13] Amberin Zaman, “Pentagon Floats Plan for Its Syrian Kurd Allies to Partner with Assad Against ISIS,” Al-Monitor, January 22, 2024, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2024/01/pentagon-floats-plan-its-syrian-kurd-allies-partner-assad-against-isis; Charles Lister, “America Is Planning to Withdraw From Syria—and Create a Disaster,” Foreign Policy, January 24, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/01/24/america-is-planning-to-withdraw-from-syria-and-create-a-disaster/.

[14] MENASource, “Trump Withdraws US Troops from Northern Syria,” Atlantic Council, October 7, 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/trump-withdraws-us-troops-from-northern-syria/.

[15] Hamidreza Azizi and Julien Barnes-Dacey, “Beyond Proxies: Iran’s Deeper Strategy in Syria and Lebanon,” European Council on Foreign Relations, June 5, 2024, https://ecfr.eu/publication/beyond-proxies-irans-deeper-strategy-in-syria-and-lebanon/.

[16] Maya Gebeily, Parisa Hafezi, and Alexander Cornwell, “Exclusive: US, UAE Discussed Lifting Assad Sanctions in Exchange for Break with Iran, Sources Say,” Reuters, December 2, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-uae-discussed-lifting-assad-sanctions-exchange-break-with-iran-sources-say-2024-12-02/.

[17] Maya Gebeily, Parisa Hafezi, and Alexander Cornwell, “Exclusive: US, UAE Discussed Lifting Assad Sanctions in Exchange for Break with Iran, Sources Say,” Reuters, December 2, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-uae-discussed-lifting-assad-sanctions-exchange-break-with-iran-sources-say-2024-12-02/.

[18] CENTCOM, “Defeat ISIS Mission in Iraq and Syria for January–June 2024,” CENTCOM, July 16, 2024, https://www.centcom.mil/MEDIA/PRESS-RELEASES/Press-Release-View/Article/3840981/defeat-isis-mission-in-iraq-and-syria-for-january-june-2024/#:~:text=%E2%80%93%20From%20January%20to%20June%202024,several%20years%20of%20decreased%20capability; Sirwan Kajjo, “Recent US Strikes Spotlight Growing Islamic State Threat in Syria,” VOA News, November 1, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/recent-us-strikes-spotlight-growing-islamic-state-threat-in-syria/7848255.html; Charles Lister, “CENTCOM Says ISIS Is Reconstituting in Syria and Iraq, but the Reality Is Even Worse,” Middle East Institute, July 17, 2024, https://www.mei.edu/publications/centcom-says-isis-reconstituting-syria-and-iraq-reality-even-worse.

[19] Reuters, “Assad Opponents in Syria Protest Turkish ‘Reconciliation’ Call,” Reuters, August 12, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/assad-opponents-syria-protest-turkish-reconciliation-call-2022-08-12/; Ece Toksabay and Ali Kucukgocmen, “Turkey Has No Preconditions for Dialogue with Syria – Foreign Minister,” Reuters, August 23, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkey-does-not-have-preconditions-dialogue-with-syria-foreign-minister-2022-08-23/.

[20] Al Arabiya, “Syrian Deputy Foreign Minister: Saudi-Iranian Reconciliation Will Put an End to Interference in the Region,” Al Arabiya, June 21, 2023, https://www.alarabiya.net/arab-and-world/syria/2023/06/21/%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%A6%D8%A8-%D9%88%D8%B2%D9%8A%D8%B1-%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A7-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B5%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B9%D9%88%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%8A%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%B3%D8%AA%D8%B6%D8%B9-%D8%AD%D8%AF%D8%A7-%D9%84%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%AF%D8%AE%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85.

[21] Hoshang Hasan, “Elections in Northeast Syria: A Step Towards Stabilization Amid Regional Turmoil,” Kurdish Peace Institute, June 4, 2024, https://www.kurdishpeace.org/research/government/elections-in-northeast-syria-a-step-towards-stabilization-amid-regional-turmoil/.

[22] Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, “Turkish-Syrian Rapprochement: A Path Studded with Conflicting Aims,” Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, August 20, 2024, https://studies.aljazeera.net/en/policy-briefs/turkish-syrian-rapprochement-path-studded-conflicting-aims.

[23] The Syrian Observer, “Hemeimeem Base: Turkish-Syrian Meeting under Russian Auspices,” Syrian Observer, June 19, 2024, https://syrianobserver.com/foreign-actors/hemeimeem-base-turkish-syrian-meeting-under-russian-auspices.html.

[24] Emirates Policy Center, “A Bumpy Road: The Future of Turkish-Syrian Normalization,” Emirates Policy Center, July 22, 2024, https://epc.ae/en/details/scenario/a-bumpy-road-the-future-of-turkish-syrian-normalization.

[25] Al Jazeera, “Syria’s al-Assad Says Turkey Rapprochement Efforts Unsuccessful,” Al Jazeera, August 25, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/8/25/syrias-al-assad-says-turkey-rapprochement-efforts-unsuccessful.

[26] Paul Iddon, “Is Turkey Gearing Up for a New Military Offensive Against Syria’s Kurds?,” The New Arab, June 5, 2024, https://www.newarab.com/analysis/turkey-gearing-new-offensive-against-syrias-kurds.

[27] The Syrian Observer, “Washington Expresses Position on Elections Planned by Autonomous Administration,” Syrian Observer, September 16, 2024, https://syrianobserver.com/foreign-actors/washington-expresses-position-on-elections-planned-by-autonomous-administration.html.

[28] Jared Szuba, “US Military in Syria Stands Down as HTS Drives Back Assad Regime, Kurdish Forces,” Al-Monitor, December 2, 2024, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2024/12/us-military-syria-stands-down-hts-drives-back-assad-regime-kurdish-forces.

[29] The Syrian Observer, “Syria and Iraq Enhance Security Ties with New Cooperation Agreement,” Syrian Observer, May 13, 2024, https://syrianobserver.com/foreign-actors/syria-and-iraq-enhance-security-ties-with-new-cooperation-agreement.html; The Syrian Observer, “Syria and Iraq Forge Stronger Ties: Focus on Security and Economic Cooperation,” Syrian Observer, June 6, 2024, https://syrianobserver.com/foreign-actors/syria-and-iraq-forge-stronger-ties-focus-on-security-and-economic-cooperation.html.

[30] Ezgi Akin, “Iraq’s PM Says Baghdad Mediating Potential Syria-Turkey Reconciliation,” Al-Monitor, June 1, 2024, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2024/05/iraqs-pm-says-baghdad-mediating-potential-syria-turkey-reconciliation.

[31] Hanna Davis, “EU-Lebanon Aid Deal Blows Back on Syrian Refugees,” Syria Direct, May 22, 2024, https://syriadirect.org/eu-lebanon-aid-deal-blows-back-on-syrian-refugees/.

[32] Mared Gwyn Jones, “Cyprus and EU-Funded Lebanese Forces Complicit in Forced Returns of Syrian Refugees, Report Claims,” EuroNews, September 4, 2024, https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2024/09/04/cyprus-and-eu-funded-lebanese-forces-complicit-in-forced-returns-of-syrian-refugees-report; Human Rights Watch, “Lebanon: Armed Forces Summarily Deporting Syrians,” Human Rights Watch, July 5, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/07/05/lebanon-armed-forces-summarily-deporting-syrians.

[33] The Syrian Observer, “Brussels VIII: Continuing the Cycle Without Progress in Syrian Aid Strategy,” The Syrian Observer, May 9, 2024, https://syrianobserver.com/foreign-actors/brussels-viii-continuing-the-cycle-without-progress-in-syrian-aid-strategy.html.

[34] Simone De La Feld, “Italy and 7 Other EU Countries Call on Brussels for a Change of Strategy on Syria,” EUNews, July 22, 2024, https://www.eunews.it/en/2024/07/22/italy-and-7-other-eu-countries-call-on-brussels-for-a-change-of-strategy-on-syria/; Ibrahim Hamidi, “Exclusive: European Push to End Long Isolation of Syria’s Regime,” Majalla, July 27, 2024, https://en.majalla.com/node/321644/documents-memoirs/exclusive-european-push-end-long-isolation-syria%E2%80%99s-regime.

[35] Ibrahim Hamidi, “Exclusive: European Push to End Long Isolation of Syria’s Regime,” Majalla, July 27, 2024, https://en.majalla.com/node/321644/documents-memoirs/exclusive-european-push-end-long-isolation-syria%E2%80%99s-regime.

[36] The Syrian Observer, “EU Moves Towards Reassessment of Syria Policy,” The Syrian Observer, September 18, 2024, https://syrianobserver.com/foreign-actors/eu-moves-towards-reassessment-of-syria-policy.html.

[37] Karam Shaar and Steven Heydemann, “Networked Authoritarianism and Economic Resilience in Syria,” Brookings, August 26, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/networked-authoritarianism-and-economic-resilience-in-syria/.

[38] Interview with a Syrian analyst who must remain anonymous due to the sensitive nature of his work providing security advice to NGOs on the ground in Syria.