In the Global South, energy-related issues are among the most urgent. The term Global South describes countries classified as underdeveloped, less developed, or generally developing.1 Though not always, these nations are mostly in the Southern Hemisphere; many of them are found in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. According to the International Energy Agency,2 over 750 million people worldwide lack access to electricity, most of them residing in developing countries. Inadequate energy access fuels social inequalities, slows down economic progress and aggravates poverty, and complicating these issues is the reliance on centralized grids, sometimes beset with restricted reach and inefficiencies. Political elements like corruption and monopolistic control compromise efforts toward energy equity; illegal financing and opaque methods often direct funds intended for public benefit.3 Dealing with these issues requires innovative initiatives that not only increase energy access but also encourage openness and responsibility for energy management systems. In this regard, blockchain technology acts as an alternative as it promotes equal distribution while decentralizing energy systems.

Blockchain, the technology that powers cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, has become internationally known and is emerging as a transforming tool across sectors, including energy.4 Using blockchain’s distributed ledger system helps energy distribution move from conventional, centralized approaches to more fair and effective ones. Blockchain allows communities to create, trade, and consume energy locally without depending on a centralized authority.5 Peer-to-peer (P2P), involving energy trade that allows prosumers to sell their surplus electricity directly to local consumers without the need for a retailer,6 and the building of microgrids, demonstrate how blockchain empowers communities to produce, trade, and consume energy domestically. The adoption of blockchain technology also facilitates supply chain management in energy production and distribution since its transparency and traceability reduce risks associated with corruption and inefficiency. Smart contracts inside blockchain networks enable automation in energy systems, therefore offering both operational dependability and cost savings.7 These developments also bring challenges involving the necessity of cybersecurity policies and legal systems to control the changing dynamics of energy trade.

Particularly crucial in areas where reliance on central authorities has maintained energy disparities is the decentralization enabled by blockchain. Blockchain technology can upend established monopolistic systems and reduce the impact of dishonest stakeholders by delegating power appropriately. In the Global South, where lack of transparency in energy governance has been a constraint to sustainable development,8 the potential of blockchain to improve responsibility is critical. Furthermore, the democratization of energy access made possible by technology complements world initiatives to close infrastructural gaps and empower underprivileged regions.

Blockchain technology has the potential to transform Global South energy systems by enabling decentralized, transparent, and fair energy delivery. Blockchain presents a practical route toward energy justice and sustainability by means of addressing important problems related to corruption, infrastructural shortcomings, and monopolistic control. This paper aims to highlight how blockchain adoption can empower local communities, change the governance of energy systems, and reinterpret conventional power dynamics in underdeveloped and developing nations. The implementation of blockchain can strengthen decentralized energy generation, storage, and distribution while addressing infrastructure challenges and empowering local populations.

Figure 1: Global North vs. Global South Map

Source: Author’s creation using mapchart.net

Bridging the Access Gap

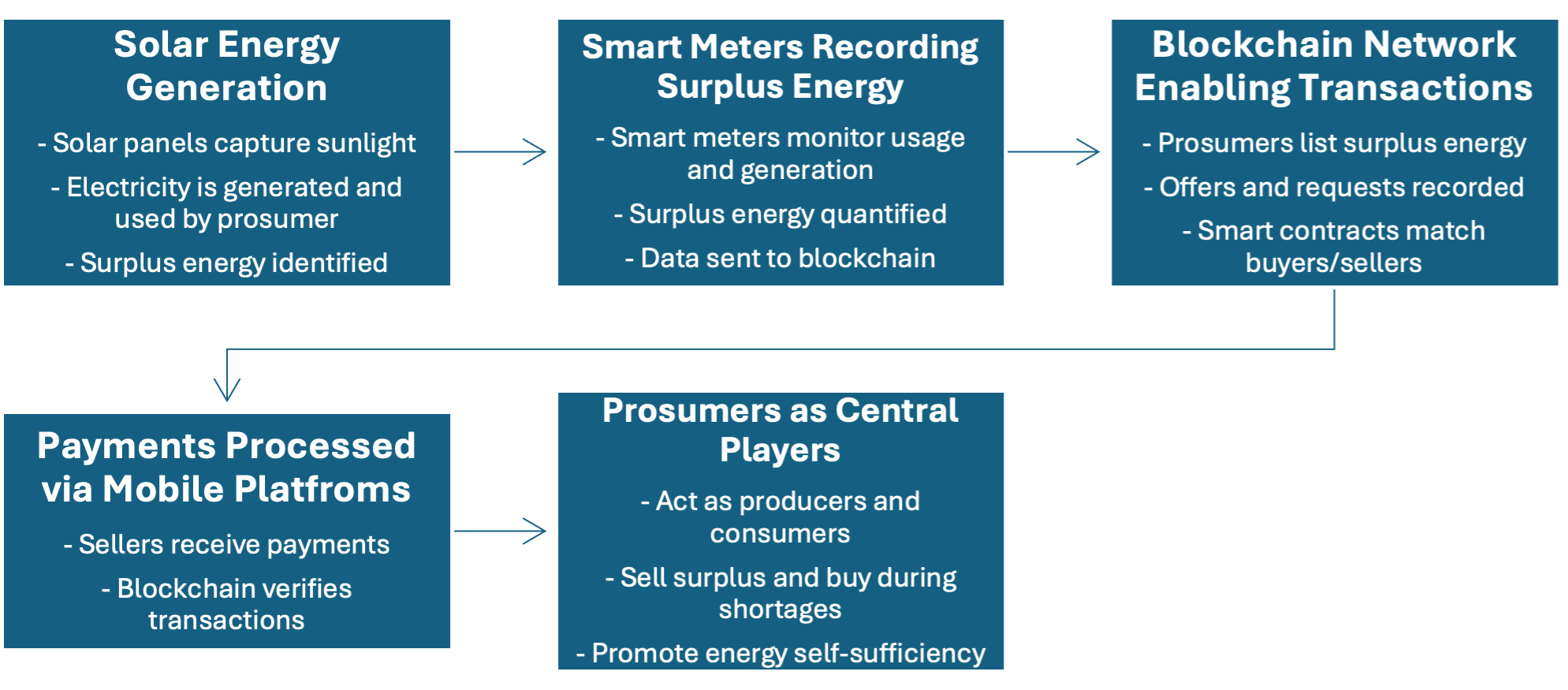

The foundation of blockchain’s potential in energy systems is decentralization. Blockchain enables decentralized energy generation and delivery,9 in contrast to centralized grids that rely on massive infrastructure and centralized control. Communities can produce and store power on their own by using Distributed Energy Resources (DERs), such as wind turbines and solar panels, as localized energy hubs. Using blockchain-enabled P2P energy trading platforms, homes with solar panels can generate electricity, store extra energy in batteries, and sell extra power to neighbors.10 This concept lessens dependency on centralized authorities while simultaneously democratizing energy access.

In Bangladesh, SOLshare made its debut as the country’s P2P electricity trading network, making it possible for rural homes to directly exchange excess solar energy with their neighbors. With the help of smart meters that enable real-time energy transactions, this system links solar home systems via a low-voltage direct current grid.11 SOLshare guarantees smooth payments by integrating mobile money systems, turning energy users into engaged “prosumers” who may profit from their supply of surplus electricity.12 In addition to improving energy access, this strategy encourages the effective use of regional renewable resources, supporting Bangladesh’s objective of boosting the integration of renewable energy.13

The efficiency of decentralized energy systems is further improved by blockchain’s integration with smart contracts. Blockchain-encoded self-executing agreements known as smart contracts allow for automated transactions based on preset criteria.14 By removing the need for middlemen, a smart contract can facilitate real-time buy-and-sell energy agreements between producers and consumers.15 Transparency is guaranteed, settlement times are shortened, and transaction costs are decreased because of this automation. Additionally, decentralized energy systems optimize energy utilization in communities by utilizing dispersed resources locally and reducing transmission losses.

The integration of DERs is further improved by decentralized smart grids driven by blockchain technology, which also addresses issues with traditional networks in managing intermittent renewable energy sources. These smart grids use the decentralized and secure platform of blockchain technology to control energy flow effectively. This allows for dynamic supply and demand balancing, which keeps the grid stable even during periods of high usage.16 Blockchain technology has been used by Renova Energy in Brazil to improve energy management17 and encourage the use of decentralized renewable energy in rural areas.18 P2P energy trading is made possible by this effort, which combines blockchain-based platforms with DERs like wind turbines and small-scale solar farms. Renova Energy enables direct transactions between energy providers and consumers without the use of middlemen by utilizing blockchain’s efficiency and transparency. Energy trade agreements are automated with smart contracts, which guarantee real-time settlements and lower transaction costs. In enabling local groups to independently produce, store, and exchange electricity, this concept lessens dependency on the centralized grid. This project tackles inequalities in energy availability in Brazil, especially in isolated areas with inadequate grid infrastructure.

The decentralized method also maximizes the use of locally accessible renewable resources and minimizes transmission losses. The achievement of Renova Energy demonstrates how blockchain technology could revolutionize energy systems throughout the Global South. The company’s emphasis on localized solutions not only improves energy accessibility but also advances Brazil’s larger objectives for sustainability and renewable energy.19 Additionally, blockchain-based energy trading platforms have been created to make P2P energy trades easier. By enabling prosumers, people who generate and consume energy, to exchange excess energy with other consumers directly, these systems encourage the production and consumption of energy locally. In addition to lowering dependency on centralized grids, this gives communities the ability to economically and sustainably meet their energy needs. Furthermore, the automation and efficiency of smart grids are improved when blockchain technology is combined with artificial intelligence (AI) in energy management systems. Blockchain guarantees the safe and transparent execution of energy transactions through smart contracts, while AI algorithms can forecast patterns in energy supply and demand.20 Real-time energy distribution adjustments are made possible by this combination, which maximizes DER utilization while preserving grid stability. Communities may successfully incorporate DERs and create a more effective and sustainable energy infrastructure by implementing blockchain-based decentralized smart grids. In addition to addressing the shortcomings of conventional grids, this paradigm shift is essential for closing the gap in energy access, especially in underserved areas.

The expense of extending centralized grid infrastructure to isolated and underserved communities is one of the biggest obstacles to energy availability in the Global South. This requires enabling decentralized energy solutions that avoid the need for significant grid expansions; however, blockchain technology offers an alternate route. Blockchain yields the potential to reduce reliance on massive infrastructure by utilizing DERs and localized energy networks, delivering energy solutions to the people who need them most.21

Blockchain technology is contributing to energy management through transparency and decentralized control. This change maximizes the usage of DERs, such as community wind turbines and small-scale solar farms, while empowering local communities. Blockchain-based microgrids have been deployed in South Africa by Cenfura in Johannesburg. This microgrid supplies a 216-unit condominium building with dependable electricity thanks to its 500 kW of rooftop solar photovoltaic capacity and 672 kWh of battery storage.22 The idea proposes lowering infrastructure costs and dependence on centralized grids by using blockchain for energy transactions. Adopting decentralized energy systems based on blockchain technology can result in significant cost reductions. Governments and local communities can reallocate funds to vital sectors like healthcare, education, and economic development by avoiding the exorbitant expenses of constructing and maintaining traditional grid infrastructure. The Indian company Tata Power Delhi Distribution Limited started a trial project that uses blockchain technology to enable the P2P trade of solar energy.23 This program encourages the effective use of renewable energy sources, lowers operating expenses, and simplifies energy transactions. Additionally, the openness of blockchain guarantees that all energy flows and transactions are documented and available, promoting participant trust.24 The localized character of decentralized systems and their transparency enables the efficient use of dispersed resources, thus limiting the demand for expensive infrastructure. Blockchain technology is a potential solution to close the energy access gap and advance equitable resource distribution by enabling communities to manage their energy demands in a sustainable and cost-effective manner.

Education and capacity-building initiatives are crucial to empower communities to harness the full potential of blockchain. Providing training on blockchain technology and decentralized energy systems can equip individuals with the skills needed to manage and maintain local energy networks. Additionally, partnerships between governments, private sector actors, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can mobilize resources and expertise to scale blockchain-based energy solutions. Blockchain’s potential to revolutionize energy access in the Global South is immense, but it is not without challenges. Issues such as regulatory uncertainty, cybersecurity risks, and the digital divide must be addressed to ensure the successful implementation of blockchain-based energy systems.25 Encouraging collaboration among stakeholders is key to addressing these challenges while realizing the potential of blockchain. The technology behind blockchain offers a pathway to bridge the energy access gap in the Global South by enabling decentralized, transparent, and efficient energy systems. This can overcome infrastructure challenges, empower local communities, and support sustainable energy practices.

Figure 2: P2P Energy Trading & Blockchain

Source: Author’s creation

A Tool for Inclusivity or Exclusion?

Blockchain technology has the potential to change in the Global South. In the context of inclusiveness and exclusion, where it can be a double-edged sword, its disruptive potential is most apparent. Blockchain technology can contribute to promoting equity and accountability, but if its implementation ignores significant infrastructural and accessibility issues, it could exacerbate pre-existing disparities.

The ability of blockchain to promote greater equity is one of its most alluring benefits for energy systems. Blockchain could reduce corruption, a recurring problem in many poor countries, by producing transparent and unchangeable records of energy transactions.26 The most vulnerable groups are disproportionately affected by corruption in energy distribution, which frequently results in exorbitant costs and resource misallocation. In ensuring that every transaction can be verified, blockchain’s decentralized ledger can lower the likelihood of tampering and promote trust in the energy markets.27

The accountability and transparency of blockchain technologies play a key role in empowering communities by mitigating problems associated with corruption and poor management. Blockchain guarantees equitable distribution and use of resources by documenting all transactions and energy transfers on a fixed ledger.28 Increased participation and cooperation within communities are encouraged by the trust that is developed among stakeholders. PowerGen Renewable Energy is a prime example of this strategy. Located in sub-Saharan Africa, the company operates in Kenya, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Tanzania.29 It has successfully established more than 100 mini-grids, providing approximately 120,000 people and more than 2,200 microbusinesses with electricity.30 Real-time data analytics and smart metering are key components of these systems that ensure transparent tracking of energy production, consumption, and revenue distribution. This openness improves operational effectiveness and ensures that everyone in the community benefits equally. Numerous rural areas now have access to dependable electricity thanks to the installation of solar-powered mini-grids. Radio and public announcement systems were employed in a gender-focused marketing campaign in the Bo district to highlight the advantages of electricity, such as the ability to do household tasks and allow children to study at night.31 This program promoted inclusivity and fair resource distribution by raising awareness and encouraging women’s involvement in energy management and usage.

A scalable, distributed renewable energy platform has also been established because of PowerGen’s cooperation with foreign investors and development groups, with the goal of deploying 120 MW of renewable power throughout Africa.32 In providing power to underserved areas and creating substantial economic activity and job possibilities, the platform seeks to assist around 70,000 households.33 The project’s accountability and transparency procedures guarantee that resources are distributed equitably, encouraging cooperation and confidence among participants. PowerGen aims to tackle corruption and poor management by incorporating blockchain technology into decentralized energy networks, guaranteeing that resources are used efficiently and fairly. In addition to empowering people, this strategy supports economic expansion and sustainable development throughout the continent.

Despite these advancements, blockchain technology poses several risks for exclusion, especially in areas with weak digital infrastructure and low levels of literacy. In addition to dependable internet access, blockchain-compatible hardware and software must be available to access blockchain-based energy systems. Such requirements provide significant obstacles in many Global South areas with poor digital infrastructure.

Moreover, digital literacy continues to be a primary constraint. Blockchain systems entail intricate technical procedures that people with little education to no experience with digital technologies may struggle with regarding accessibility. A situation where blockchain-enabled energy solutions specifically benefit an elite group while excluding large sectors of the populace who lack the resources or expertise to engage could result from this digital divide if left unaddressed. Another important consideration is affordability. Although blockchain can eventually reduce transaction costs, its initial deployment sometimes necessitates a large infrastructure and training expenditure.34 The cost of using blockchain technology in low-income communities, from buying suitable devices to paying transaction fees, may exceed its advantages, hence escalating rather than reducing already-existing disparities.

To overcome obstacles and guarantee that blockchain’s inclusivity potential is fully realized, furthering international collaborations is essential. Blockchain technology can be used by NGOs and development organizations to improve the effectiveness and transparency of aid initiatives pertaining to energy. Aid groups may guarantee that money is spent as intended by using blockchain for real-time monitoring and record-keeping.35 Increased participation and cooperation within communities are encouraged by the trust that is developed among stakeholders because of this transparency. According to the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, blockchain technology can greatly improve energy systems’ accountability and transparency, which is essential for the efficient use of aid funds.36 Furthermore, by offering an open platform for monitoring donations and results, blockchain can help local communities, governments, and foreign contributors work together. The United Nations Development Programme highlights the value of these cooperative approaches, pointing out that public-private partnerships, budget allocation, and capacity-building are critical to the success of digital projects.37

To overcome obstacles such as lack of digital literacy and inadequate infrastructure, international aid initiatives must also give priority to capacity-building. Communities can be prepared to engage in blockchain-based energy systems by investing in education and training initiatives. Capacity-building workshops on advancing the digital economy were held by the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, emphasizing the necessity of strong legislative and regulatory frameworks to encourage blockchain-based digital innovation.38 To ensure that everyone can benefit from blockchain, collaborations with local governments and private sector players are additionally crucial for building the required infrastructure involving internet access and renewable energy installations. To successfully address digital disparities in developing countries and overcome funding obstacles, the Internet Governance Forum 2024 emphasized the significance of stakeholder collaboration.39 Blockchain technology offers an alternative way to improve energy distribution’s efficiency, accountability, and transparency when used in international charity initiatives.

Blockchain technology enables microtransactions in underdeveloped rural areas, enhancing the equity and inclusivity of energy access. The financial limitations of rural families, where people might not have the funds to pay for high energy quotas, are frequently disregarded by traditional energy systems. Pay-as-you-go (PAYG) energy solutions are made possible by blockchain-based systems, which let customers buy just the energy they require and can afford at any given time.40 The use of PAYG solar systems has greatly expanded access to energy in Sub-Saharan Africa. To increase financial inclusion and offer rural communities reasonably priced energy solutions, companies such as M-KOPA Solar have integrated solar electricity, Internet of Things (IoT) security, mobile payments, and a driven sales and support network.41 In addition to addressing rural households’ financial constraints, these blockchain-enabled PAYG solutions encourage sustainable energy use. These systems lessen the pressure of high upfront prices and accommodate the erratic revenue streams typical of rural locations by enabling customers to pay for electricity in tiny, manageable chunks. This adaptability promotes the use of renewable energy sources, which has wider positive effects on the environment and the economy. Additionally, blockchain technology’s security and transparency promote user trust by guaranteeing that transactions are accurately recorded and impenetrable.42 In order to promote community acceptance and involvement in decentralized energy programs, this degree of responsibility is essential. One practical way to get around the financial obstacles rural households have in obtaining sustainable and dependable electricity is by integrating blockchain technology into PAYG energy systems. Blockchain improves energy justice and inclusivity by enabling microtransactions and guaranteeing transparent operations, enabling communities to efficiently satisfy their energy demands.

Blockchain could be a tool for inclusion or exclusion in energy systems, depending on how it is applied. Even if the technology provides innovative ways to improve accountability, enable fair pricing, and hinder corruption, these advantages cannot be achieved without removing the systemic and structural constraints that prevent access. Technology companies, development groups, and policymakers must cooperate to make sure blockchain is implemented in ways that advance inclusivity rather than exacerbate pre-existing disparities.

Through a strategy that integrates technological advancements with infrastructure development and capacity-building, the Global South can utilize blockchain technology to establish more sustainable and equitable energy systems. In addition to technical knowledge, this calls for a dedication to comprehending and resolving the difficulties underprivileged populations experience. Blockchain is neither always exclusive nor inclusive; its effects are contingent upon the goals and tactics used to implement it. Therefore, a vision of sustainability and fairness that leaves no actor unaccounted for must serve as the foundation for its role in the Global South.

Governance Implications

Blockchain technology is transforming governance structures in a variety of sectors, and its influence on energy systems in the Global South is no exception. Blockchain introduces both opportunities and challenges and challenges traditional governance paradigms. The implications for governance are varied, encompassing the necessity for new regulatory frameworks, shifts in geopolitical dynamics, and the transition of energy monopolies.

The potential to undermine entrenched energy monopolies is one of the most significant governance implications of blockchain in the energy sector. In the Global South, traditional energy markets are frequently monopolized by a small number of state-owned or private entities that regulate production, distribution, and pricing. Inefficiencies, corruption, and unequal access to energy resources are frequently the consequence of these monopolies. In challenging existing monopolies and promoting decentralized energy systems, blockchain technology has the potential to substantially reform the energy sector in the Global South. In numerous developing countries, traditional energy markets are frequently monopolized by a small number of state-owned or private entities that regulate production, distribution, and pricing. This results in inefficiencies and restricted access to energy resources. By facilitating P2P energy trading platforms, blockchain technology can disrupt these centralized systems, enabling individuals and small businesses to directly generate, trade, and sell surplus energy to others without intermediaries.43 A blockchain-based P2P energy trading platform was implemented by the T77 project in Bangkok, which was utilized by several significant energy consumers, such as shopping centers and schools.44 Participants had the opportunity to exchange surplus solar energy, which would improve energy efficiency and decrease their dependence on conventional energy providers. The transition to decentralized energy systems through blockchain technology is confronted with political opposition, despite the advantages. Monopolies that are deeply rooted in political power structures may advocate against the implementation of blockchain technology to preserve their authority.45

In the context of the Global South, the implementation of blockchain in energy governance also presents significant regulatory challenges. The development of new regulations that balance innovation with supervision is necessary, as traditional legal frameworks are ill-equipped to address the characteristics of blockchain-based systems. The transparent nature of blockchain technology, while beneficial for accountability, raises concerns regarding the protection of sensitive data, including financial transactions and consumer energy usage. The inclusivity and efficacy of blockchain-based energy markets may be undermined if individuals and businesses are hesitant to participate in the absence of privacy safeguards.46

An additional obstacle is the potential for energy fraud. Although blockchain’s immutability renders it impervious to manipulation, vulnerabilities may still develop because of inadequately designed smart contracts, cyberattacks, or collusion among participants.47 To mitigate these risks, regulatory frameworks must incorporate provisions for auditing blockchain systems, enforcing accountability, and resolving disputes. Technological supervision is equally essential. Governments in the Global South frequently lack the necessary resources and expertise to effectively monitor and regulate blockchain systems. It is imperative to implement capacity-building initiatives, such as partnerships with technology providers and training programs for regulators, to guarantee the transparent and equitable operation of blockchain systems. Additionally, to prevent fragmentation and guarantee integration into existing energy systems, governments must establish explicit standards for the interoperability of blockchain platforms.

Energy governance implementation in blockchain technology has extensive geopolitical implications for the Global South. The global energy alliances and power dynamics can be altered by blockchain, which can reduce dependency on fossil fuels by facilitating decentralized and renewable energy systems. The dependence on imported fossil fuels is a substantial economic and geopolitical vulnerability for numerous countries in the Global South. Energy security can be improved and exposure to volatile international oil and gas markets can be reduced by blockchain’s potential to facilitate the transition to renewable energy through mechanisms such as decentralized energy infrastructure and carbon credit trading.48 This change could also be in accordance with the global climate objectives, establishing the Global South as a leader in sustainable energy initiatives. Furthermore, the implementation of blockchain-based energy systems has the potential to attract foreign investments. International investors are increasingly emphasizing sustainable and transparent energy projects, and blockchain’s capacity to generate verifiable records of energy production and consumption can support investor confidence.49 Countries in the Global South can expedite the development of renewable energy infrastructure and stimulate economic growth by cultivating an investment-friendly environment.

Nevertheless, the geopolitical implications of blockchain are not without obstacles. The transition to blockchain-based energy systems may result in opposition from countries that export fossil fuels, as they may perceive the technology as a threat to their economic interests. Additionally, blockchain infrastructure and governance may be dominated by technologically sophisticated countries, which could result in the development of novel forms of digital dependency due to discrepancies in blockchain adoption across regions.50 To mitigate these risks, the Global South must engage in regional initiatives that prioritize equitable access to blockchain resources, capacity development, and technology transfer.

The potential of blockchain to revolutionize energy governance in the Global South is promising; however, its success is contingent upon the resolution of the governance challenges it introduces. To incorporate the distinctive attributes of blockchain, regulatory frameworks must be modified to prioritize technological oversight, fraud prevention, and privacy. The implementation of blockchain technology must be consistent with strategies that promote regional cooperation, attract investments, and improve energy security on a geopolitical level.

Conclusion

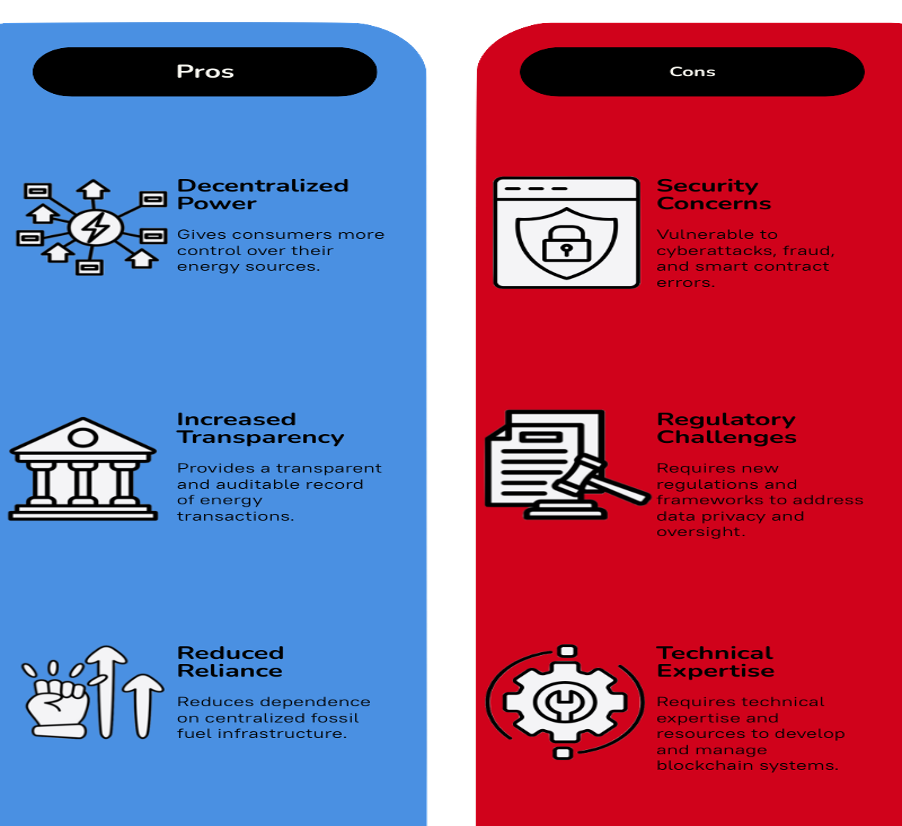

Blockchain technology leads the way in changing energy systems and offers opportunities to enhance access, equity, and governance, especially in the Global South. Blockchain is a main driver of sustainable development since it may decentralize energy markets, promote transparency, and empower communities by fair distribution of resources. Blockchain alone cannot sufficiently close the energy access gap in the Global South; a comprehensive strategy combining blockchain with other complementary technologies and policies is required. Blockchain combined with IoT devices can improve energy monitoring and management, therefore allowing exact control of energy flows. Policies supporting the acceptance of renewable energy sources and encouraging community-driven energy initiatives can similarly encourage change to distributed energy systems.

Blockchain holds the power to solve long-standing issues in energy access and governance by allowing P2P energy trading, reducing corruption, and drawing investments into renewable energy. Realizing this promise, nevertheless, calls for addressing technological, legal, and financial constraints. Many areas lack digital knowledge, and infrastructure runs the danger of excluding disadvantaged groups from the advantages of blockchain-based solutions. Likewise, the lack of thorough regulations begs questions around data protection, control, and fraud mitigation. In tackling long-standing problems like corruption and incompetence, the openness and responsibility in blockchain support can reach out to more communities. Blockchain guarantees equitable use of resources by tracking all transactions and energy flows on an unchangeable ledger. This openness helps stakeholders to build confidence, therefore promoting more community involvement and cooperation. Blockchain runs the danger of exacerbating rather than mending inequality without focused investments and inclusive policies.

Figure 3: Advantages and Disadvantages of Blockchain Technology in the Global South

Source: Author’s creation using piktochart.com & thenounproject.com

Coordinated effort is necessary to maximize blockchain potential and minimize these obstacles. Governments must lead by example by creating strong laws and legal systems guaranteeing fair access and responsibility in blockchain-enabled energy markets. Equally vital to equipping communities for a stronger foundation in energy are investments in digital infrastructure and education. The private sector is important in this regard for creating user-friendly blockchain systems catered to the requirements of underdeveloped nations. By means of financial resources, technical knowledge, and advocacy for inclusive blockchain use, partnerships with international organizations and development agencies can support future developments even further.

The path ahead should call for unanimous shared dedication to innovative and diverse strategies. The Global South may reorient its energy distribution by including blockchain as a tool for sustainable energy governance, therefore promoting resilience, equity, and wealth.

References

[1] Heine, Jorge, “The Global South Is on the Rise – but What Exactly Is the Global South?,” The Conversation, July 3, 2023, https://theconversation.com/the-global-south-is-on-the-rise-but-what-exactly-is-the-global-south-207959#:~:text=The%20Global%20South%20refers%20to,Africa%2C%20Asia%20and%20Latin%20America.

[2] International Energy Agency (IEA), “SDG7: Data and Projections: Access to Electricity,” 2023, https://www.iea.org/reports/sdg7-data-and-projections/access-to-electricity.

[3] Moghani, Amir Mohammad, and Reyhaneh Loni, “Review on Energy Governance and Demand Security in Oil-Rich Countries,” Energy Strategy Reviews 57 (January 2025): Article 101625, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2024.101625.

[4] Ahmed G. Gad, Diana T. Mosa, Laith Abualigah, and Amr A. Abohany, “Emerging Trends in Blockchain Technology and Applications: A Review and Outlook,” Journal of King Saud University – Computer and Information Sciences 34, no. 9 (2022): 6719–42, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2022.03.007.

[5] Claudia Antal Pop, Tudor Cioara, Marcel Antal, Vlad Mihailescu, Dan Mitrea, Ionut Anghel, Ioan Salomie, et al., “Blockchain-Based Decentralized Local Energy Flexibility Market,” Energy Reports 7 (2021): 5269–88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2021.08.118.

[6] Pornpit Wongthongtham, Daniel Marrable, Bilal Abu-Salih, Xin Liu, and Greg Morrison, “Blockchain-Enabled Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading,” Computers & Electrical Engineering 94 (2021): 107299, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2021.107299.

[7] Kirli, Desen, Benoit Couraud, Valentin Robu, Marcelo Salgado-Bravo, Sonam Norbu, Merlinda Andoni, Ioannis Antonopoulos, Matias Negrete-Pincetic, David Flynn, and Aristides Kiprakis, “Smart Contracts in Energy Systems: A Systematic Review of Fundamental Approaches and Implementations,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 158 (2022): 112013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.112013.

[8] Downes, Lauren, and Chris Reed, “Blockchain for Governance of Sustainability Transparency in the Global Energy Value Chain,” Queen Mary School of Law Legal Studies Research Paper No. 283/2018 (2018), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3236753.

[9] Gururaja H. S., Ananya Hebbar, Amisha S. Poojary, Asritam Aniruddh Bharadwaj, and Rakshitha B. R., “Decentralized Energy Trading for Grids Using Blockchain for Sustainable Smart Cities,” International Research Journal on Advanced Engineering and Humanity (IRJAEH) 2, no. 2 (2023): 1–10.

[10] Saeed, Nimrah, Fushuan Wen, and Muhammad Zeshan Afzal, “Decentralized Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading in Microgrids: Leveraging Blockchain Technology and Smart Contracts,” Energy Reports 12 (2024): 1753–64, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2024.07.053.

[11] Karim, Naimul, “Bangladeshi Solar-Sharing Start-up Aims to Cut Power Waste,” Reuters, July 2, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/bangladeshi-solar-sharing-start-up-aims-to-cut-power-waste-idUSKBN24332I.

[12] International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Innovation Landscape for a Renewable-Powered Future: Solutions to Integrate Variable Renewables, Abu Dhabi: IRENA, 2019, https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2019/Feb/IRENA_Innovation_Landscape_2019_report.pdf.

[13] Sajid, Eyamin, “Solshare Backs Businesses by Sharing Solar Energy,” The Business Standard, July 13, 2020, https://www.tbsnews.net/bangladesh/energy/solshare-backs-businesses-sharing-solar-energy-105445.

[14] “Smart Contract,” ScienceDirect, Accessed January 22, 2025, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/computer-science/smart-contract.

[15] Anna K, “How to Build a Decentralized Energy Brokerage Platform: Blockchain and Smart Contracts for Energy Trading,” Blaize Blog, October 28, 2024, https://blaize.tech/blog/building-a-decentralized-energy-brokerage-platform-blockchain-and-smart-contracts-for-energy-trading/.

[16] Ullah, Nazir, Waleed Mugahed Al-Rahmi, Fahad Alblehai, Yudi Fernando, Zahyah H. Alharbi, Rinat Zhanbayev, Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan, and Mohammed Habes, “Blockchain-Powered Grids: Paving the Way for a Sustainable and Efficient Future,” Heliyon 10, no. 10 (2024): e31592, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31592.

[17] Renova Energia, “Company Overview.” Renova Energia Institutional Website, Accessed January 22, 2025, https://ri.renovaenergia.com.br/en/company/.

[18] Taherdoost, Hamed, “Blockchain Integration and Its Impact on Renewable Energy,” Computers 13, no. 4 (2024): 107, https://doi.org/10.3390/computers13040107.

[19] RENOVA Inc, “Sustainability Initiatives,” RENOVA Sustainability Page, Accessed January 22, 2025, https://www.renovainc.com/en/sustainability/.

[20] Vionis, Panagiotis, and Theodore Kotsilieris, “The Potential of Blockchain Technology and Smart Contracts in the Energy Sector: A Review,” Applied Sciences 14, no. 1 (2024): 253, https://doi.org/10.3390/app14010253.

[21] Taherdoost, “Blockchain Integration and Its Impact on Renewable Energy,” 107.

[22] Jones, Jonathan Spencer, “Blockchain Renewable Energy Microgrids to Be Deployed in South Africa,” Smart Energy International, March 3, 2021, https://www.smart-energy.com/industry-sectors/distributed-generation/blockchain-renewable-energy-microgrids-to-be-deployed-in-south-africa/.

[23] Tata Power-DDL, “Tata Power-DDL Rolls out Live Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Solar Energy Trading, a First-of-Its-Kind Pilot Project in Delhi,” Press Release, March 9, 2021, https://www.tatapower-ddl.com/pr-details/199/1658486/tata-power-ddl-rolls-out-live-peer-to-peer-(p2p)-solar-energy-trading,-a-first-of-its-kind-pilot-project-in-delhi.

[24] Javaid, Mohd, Abid Haleem, Ravi Pratap Singh, Rajiv Suman, and Shahbaz Khan, “A Review of Blockchain Technology Applications for Financial Services,” BenchCouncil Transactions on Benchmarks, Standards and Evaluations 2, no. 3 (2022): 100073, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbench.2022.100073.

[25] Dai, Fangfang, Yue Shi, Nan Meng, and Zhiguo Ye, “From Bitcoin to Cybersecurity: A Comparative Study of Blockchain Application and Security Issues,” In 2017 4th International Conference on Systems and Informatics (ICSAI), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322326515_From_Bitcoin_to_cybersecurity_A_comparative_study_of_blockchain_application_and_security_issues.

[26] Raycraft, Rachel Davidson, and Ashley Lannquist, “Blockchain Alone Can’t Prevent Crime, but These 5 Use Cases Can Help Tackle Government Corruption,” World Economic Forum, July 13, 2020, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2020/07/5-ways-blockchain-could-help-tackle-government-corruption/.

[27] Hayes, Adam, “Blockchain Facts: What Is It, How It Works, and How It Can Be Used,” Investopedia, September 16, 2024, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/blockchain.asp.

[28] Daniel, Desiree and Chinwe Ifejika Speranza, “The Role of Blockchain in Documenting Land Users’ Rights: The Canonical Case of Farmers in the Vernacular Land Market,” Frontiers in Blockchain 3 (May 12, 2020), https://doi.org/10.3389/fbloc.2020.00019.

[29] African Development Bank, “African Development Bank, PowerGen, and Partners Launch Transformative Renewable Energy Platform to Scale Clean Energy Access Across the Continent,” African Development Bank Press Release, January 17, 2025, https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/african-development-bank-powergen-and-partners-launch-transformative-renewable-energy-platform-scale-clean-energy-access-across-continent-80107.

[30] Renewable Energy Performance Platform (REPP), “PowerGen: Success of Series B Funding Round in 2019,” Renewable Energy Performance Platform, December 31, 2023. https://repp.energy/project/powergen-series-b/.

[31] International Monetary Fund, “Sierra Leone: Poverty Reduction and Growth Strategy,” IMF Staff Country Reports, November 22, 2024, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2024/323/article-A001-en.xml.

[32] Energy Monitor, “PowerGen Establishes 120MW Renewable Energy Platform in Africa,” Energy Monitor, January 20, 2025, https://www.energymonitor.ai/news/powergen-120mw-renewable-energy-platform-africa/?cf-view.

[33] African Development Bank, “African Development Bank, PowerGen, and Partners Launch Transformative Renewable Energy Platform,” BusinessGhana, January 22, 2025, https://www.businessghana.com/site/news/Business/321444/African-Development-Bank,-PowerGen,-and-Partners-Launch-Transformative-Renewable-Energy-Platform.

[34] Javaid et al., “A Review of Blockchain Technology Applications for Financial Services,” 100073.

[35] FundsforNGOs, “How Can Blockchain Improve Transparency in Donor-Funded Projects?,” accessed January 2025, https://www.fundsforngos.org/all-questions-answered/how-can-blockchain-improve-transparency-in-donor-funded-projects/.

[36] Allessie, David, Maciej Sobolewski, and Lorenzino Vaccari, Blockchain for Digital Government: An Assessment of Pioneering Implementations in Public Services. Edited by Francesco Pignatelli, EUR 29677 EN. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019, https://interoperable-europe.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/document/2019-04/JRC115049%20blockchain%20for%20digital%20government.pdf.

[37] United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Digital Public Goods for the SDGs: Emerging Insights on Sustainability, Replicability, and Partnerships, New York: UNDP, 2023, https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2023-04/Digital%20Public%20Goods%20for%20the%20SDGs%20-%20Case%20Studies.pdf.

[38] Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), Final Report on Capacity Building for Digital Innovation Using Blockchain Technology. SOM Steering Committee on Economic and Technical Cooperation (SCE), Policy Partnership on Science, Technology, and Innovation (PPSTI), June 2022. https://www.apec.org/publications/2022/06/final-report-on-capacity-building-for-digital-innovation-using-blockchain-technology.

[39] Digital Watch Observatory, “Internet Governance Forum 2024,” Digital Watch, accessed January 2025, https://dig.watch/event/internet-governance-forum-2024.

[40] Masdar, “Pay-as-You-Go Model Brings Affordable Energy to Rural Areas,” March 6, 2019. https://masdar.ae/en/news/newsroom/pay-as-you-go-model-brings-affordable-energy-to-rural-areas.

[41] Efficiency for Access Coalition, Pay-As-You-Go Models: Unlocking a Financial Pathway for Underserved Individuals Through Energy Access, March 2019, https://efficiencyforaccess.org/wp-content/uploads/M-KOPA-pay-as-you-go-models.pdf.

[42] Javaid et al., “A Review of Blockchain Technology Applications for Financial Services,” 100073.

[43] Sahebi, Hadi, Mohammad Khodoomi, Marziye Seif, MirSaman Pishvaee, and Thomas Hanne, “The Benefits of Peer-to-Peer Renewable Energy Trading and Battery Storage Backup for Local Grid,” Journal of Energy Storage 63 (July 2023): 106970, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.106970.

[44] Powerledger, “T77 & O77 – BCPG, Thailand: Blockchain-Backed Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading,” Accessed January 2025, https://powerledger.io/clients/t77-bcpg-and-mea-thailand-thailand/.

[45] Atzori, Marcella, “Blockchain Technology and Decentralized Governance: Is the State Still Necessary?” Journal of Governance and Regulation 6, no. 1 (March 2017): 5–19. https://doi.org/10.22495/jgr_v6_i1_p5.

[46] Vionis and Kotsilieris, “The Potential of Blockchain Technology and Smart Contracts in the Energy Sector,” 253.

[47] Deepak, Preeti Gulia, Nasib Singh Gill, Mohammad Yahya, and others, “Exploring the Potential of Blockchain Technology in an IoT-Enabled Environment: A Review.” IEEE Access (January 2024): 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3366656.

[48] Sivaram, Tummalapenta and Saravanan B, “Recent Developments and Challenges Using Blockchain Techniques for Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading: A Review,” Results in Engineering 24 (December 2024): Article 103666, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103666.

[49] Rejeb, Abderahman, Karim Rejeb, Imen Zrelli, Edit Süle, and Mohammad Iranmanesh, “Blockchain Technology in the Renewable Energy Sector: A Co-Word Analysis of Academic Discourse,” Heliyon 10, no. 8 (April 2024): Article e29600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29600.

[50] Duan, Keru, Gu Pang, and Yong Lin, “Exploring the Current Status and Future Opportunities of Blockchain Technology Adoption and Application in Supply Chain Management,” Journal of Digital Economy 2 (December 2023): 244–288, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdec.2024.01.005.