Throughout human history, the Mediterranean has always maintained its geostrategic importance and has been referred to as the “cradle of civilizations”. Yet today it faces various challenges and crises. In the past decade, the Eastern Mediterranean has become an arena of competition in terms of geopolitics and maritime security, involving regional and global actors.

During hydrocarbon explorations conducted by Türkiye’s Oruç Reis seismic research vessel in 2020, geopolitical tensions between Türkiye and Greece brought the two countries to the brink of another hot conflict, following the Kardak Crisis in 1996. This event, which brought the issue of maritime jurisdiction areas and Türkiye’s “Blue Homeland” maritime doctrine to the forefront, marked a process in which the narratives of the two nations distinctly clashed.

Emerging as a case study in terms of diplomacy and strategic communication, this insight aims to analyze and discuss the approaches, policies, and narratives of Türkiye and Greece as well as some influential regional and global actors’ security policies concerning the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Geostrategic Importance of the Eastern Mediterranean

The Mediterranean is an ancient sea that links the continents of Africa, Asia and Europe, serving as a nexus for international maritime trade between the Atlantic and Indian oceans. Historically, the Romans claimed it as Mare Nostrum (Our Sea) in their imperial dominance.[1] While the terms “sea” and “ocean” are often used interchangeably, geographers recognize that the earth has 50 seas, one of which is the Mediterranean.[2] Despite constituting only 0.7% of the world’s seas, the Mediterranean spans 3,800 km from east to west, with a coastline of 37,000 km and a surface area of 2.5 million km2.[3] It outturns 20% of the world’s maritime trade, 20% of oil transportation, 10% of container shipment, and the transit of over 200 million passengers annually.[4] Today, there are 23 littoral states in the region, including the UK.[5] The population of Mediterranean countries, which stood at 466 million in 2010, is estimated to reach 529 million by the end of 2025.[6]

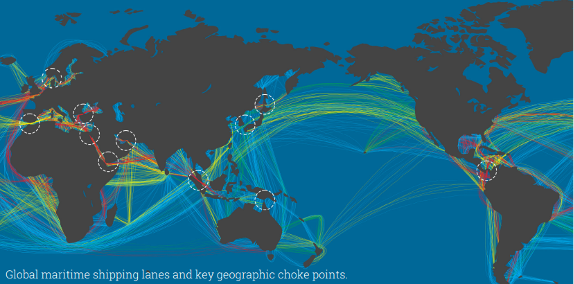

The Mediterranean is not a single sea; it is a “sum of seas” considered and interconnected together with the Alborán, Balearic, Ligurian, Tyrrhenian, Adriatic, Ionian and Aegean Seas. Italy serves as the central axis of it. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) formulated this structure in its 1953 publication “Limits of Oceans and Seas”, which confirms the historian Fernand Braudel’s conceptualization of the Mediterranean as divided into eastern and western basins.[7] The Eastern Mediterranean (East Med) is delineated as the area east of a line starting from Cape Lilibeo of Sicily in Italy to Cape Bon in Tunisia, encompassing the Tyrrhenian Sea, the Adriatic Sea, the Ionian Sea and the Aegean Sea, and extending to the coasts of Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Palestine.[8] In the Mediterranean, where key sea lines of communication from the Indo-Pacific to Europe transit, the Suez Canal, the Turkish Straits, and the Strait of Gibraltar are strategic choke points for the delivery of energy to markets, the throughput of maritime trade, and freedom of navigation.[9]

Figure 1: Global Maritime Shipping Lanes and Key Geographic Choke Points

Source: U.S. Navy CNO Navigation Plan (2022)

The Mediterranean has consistently maintained its geostrategic significance and is frequently described as the “cradle of civilizations”. However, today it encounters multiple challenges and crises. Since the early 21st century, the rapidly changing global security environment, unending turmoil and conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), civil wars in Libya and Syria, recurring political and economic crises in Lebanon, Israel’s never-ending expansionist policy against Palestine, unprecedented attacks in Gaza, and reverberations in the Red Sea, which drew keen reactions from all over the world, have made the East Med more unstable and insecure than ever.

Moreover, the rise of globalization increased maritime trade, growing energy dependencies, and the strategic importance of shipping lanes and choke points. As recent hydrocarbon discoveries have drawn the attention of global actors to the region, the East Med has become the arena of a new rivalry in terms of geopolitics and maritime security in the past ten years. There are numerous actors in the region with different weights, activities, and dimensions. Among these are the EU, NATO, the UN, China, Egypt, France, Germany, Greece, India, Iran, Israel, Italy, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Türkiye, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the UK, and the U.S., which are considered to have played active roles and pursued effective policies in the region.

The U.S., as a leading actor in the East Med geopolitics, has strengthened its military forces in the Middle East for a long time, with a policy based on three main pillars: Israel’s security, disrupting the rising influence of Russia and China, and controlling the energy resources in the region. Considering geopolitical developments since 2018, the U.S. patronage of Greece and the Greek part of Cyprus Island (GCA) can be added as a fourth pillar to this tripod. The U.S. has carried out a wide range of initiatives and investments in the region, particularly in Israel and Greece.

U.S. foreign policy includes a series of moves such as establishing a containment strategy against Russia in Eastern Europe, restricting Russia’s capability to use energy as a geopolitical tool to end Europe’s energy dependency on Russia, and disrupting China’s global economic influence within the scope of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Nevertheless, the U.S. unconditionally continues to protect and support Israel politically, militarily, and economically. Thereof, Israel’s unlawful military interventions in Syria and Lebanon alongside Gaza create deep concerns over the region.

Beijing’s influence in the Mediterranean region, which is generally shaped by its soft power approach—such as financing and investments in the fields of diplomacy, economic cooperation, infrastructure, ports and transportation—has shown an increasing trend. Many countries in MENA and Europe are involved in the BRI or have shown interest in joining. China is operating the Piraeus Port in Greece as a gateway to Europe within the BRI. On the other hand, China supports a two-state solution for Palestine and Israel and a lasting peace in the Middle East. Regarding Israel’s never-ending war in Gaza, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said, “Noting that failure to end the humanitarian disaster caused by the Palestinian-Israeli conflict today in the 21st century is a tragedy for humanity and a disgrace for civilization.”[10]

The UK’s “respectful silence” and cautious stance in the face of increasing competition for energy resources in the East Med, newly established initiatives, frictions between Türkiye and Greece, and other geopolitical issues draw attention. The UK, which has diverged in foreign policy from Europe after Brexit, has turned its attention to the Asia-Pacific and has become a staunch partner in the great power competition waged by the U.S. against China within the AUKUS alliance.

Claiming the leadership of the EU and trying to increase its influence in MENA, France put forward the “Union for the Mediterranean” initiative in 2008. The Middle East-focused initiative aims to contribute to peace, stability and security in the region. However, the footprint of France is getting smaller day by day, particularly in Africa. President Emmanuel Macron, in a recent address to the nation, stated that, as the world’s second-largest ocean power, France could reconstruct the economy through the development of its maritime strategy.

The Arabian Gulf has long been known as a sea of geopolitical competition between the Arab Gulf states led by Saudi Arabia and Iran. Analysts identify that Iran has an enduring cultural and political influence ranging from the Gulf to the East Med, particularly in Yemen, Syria, Lebanon, and so forth, and it is one of the leading actors in the Middle East.[11] Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Israel, and India also cooperate with Greece, particularly in defense and security, and they participate in various joint military exercises in the East Med. It is noteworthy that despite the historical and cultural ties with Türkiye, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE signed several cooperation agreements with Greece and the GCA in defense and energy sectors, which added complexity to the East Med geopolitics. The EU has been actively involved in the region, especially by supporting Greece and the GCA. Spain and Italy pursue a prudent soft power strategy in the East Med and take a more pragmatic approach toward Türkiye.

Based on classical and contemporary geopolitical theories, Türkiye has a rich historical background and is located at a geostrategic position in the East Med, serving as a bridge between Europe and Asia. Despite ongoing conflicts and turmoil in the surrounding geography, Türkiye stands out as a “stable platform in the midst of chaos,” as the strategist George Friedman put it, with its vision and weight beyond its borders.[12] By contrast, depicting itself as the “guarantee of Europe’s security”, Greece defines its north-east-south directions as the “arc of instability” within the framework of its defense policy and sees the region, including Türkiye, as a priority in its threat perception.[13] Türkiye and Greece have an array of deep-rooted political issues in the Aegean Sea and East Med, the most important of which are the Cyprus issue and the maritime jurisdiction disputes. While Greece does not recognize the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) as a sovereign state, Türkiye similarly does not recognize the GCA.

The Aegean Sea, due to its intricate geography encompassing nearly 3,200 islands and islets,[14] has seven chronic issues including maritime jurisdiction and sovereignty disputes, such as (1) The islands, islets and rocks, the sovereignty of which were not transferred to Greece by treaties, (2) Territorial Waters, (3) Continental Shelves, (4) Violation of the non-militarized status of the Eastern Aegean Islands, (5) Airspace Sovereignty, (6) Flight Information Region (FIR), and (7) Search and Rescue (SAR) region. Greece’s record may also include violations regarding the treatment of the Turkish minority—whose status was guaranteed under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne—as well as its draconian migration policies, including pushbacks of asylum seekers and migrants.

These complex issues, which are difficult to comprehend by those unfamiliar with the regional geopolitics, emanate from some historical events between the two NATO member countries, different interpretations of international law and, most importantly, the expansionist policy that Greece pursues relentlessly. Since gaining independence in 1830, Greece has gradually expanded its borders on several occasions, most recently by extending its territorial waters in the Ionian Sea from 6 to 12 nautical miles—moves that some observers view as reflecting elements of long-standing national aspirations such as the Megali Idea.[15] The main supporting evidence of this claim is that the physical geography of Greece by land increased from 47,517 km2 in 1832, when it was first established, to 131,957 km2 today, excluding maritime jurisdiction areas.[16]

In order to comprehend, negotiate, and resolve the disputes, Türkiye and Greece established bilateral political and military talks within their dialogue mechanisms, including (1) the meetings held between the Ministries of Defense on “Confidence Building Measures”, (2) the “Political Dialogue” meetings held between the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, (3) the “Exploratory Talks” aimed at preparing the ground for “fair, permanent, and comprehensive” solutions acceptable to both parties regarding the problems in the Aegean Sea, and (4) the “High Level Cooperation Council” meetings at the heads of state/government level.

Road to the Crisis in 2020

In 2010, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimated the presence of 1.7 billion barrels of oil, 122 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas, and 3 billion barrels of natural gas liquids in the Levant Basin,[17] as well as 1.8 billion barrels of oil, 223 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas, and 6 billion barrels of natural gas liquids in the Nile Delta Basin[18] in the East Med. The USGS updated its estimate in 2020 to 879 million barrels of oil, 286.2 trillion cubic feet of gas, and 2.2 billion barrels of gas liquids in the East Med.[19] Nevertheless, maritime jurisdiction areas in the East Med have not yet been determined by multilateral agreements of the coastal states due to a certain level of disagreement on border demarcations.

Unilateral actions by Greece—such as asserting far-reaching claims over the Turkish continental shelf and launching new initiatives in the Eastern Mediterranean—as well as steps taken by the GCA, including attempts to assert sovereignty through the signing of Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) agreements with Egypt, Lebanon, and Israel, energy cooperation deals, and licensing exploration and drilling activities in contested waters, have contributed to tensions and undermined efforts to maintain peace and stability in the region by overlooking the rights and interests of other coastal states. Türkiye and the TRNC regarded these unilateral efforts as invalid due to a lack of consent by the TRNC and violations of the Turkish continental shelf, particularly in its parcels of 1, 4, 5, 6, and 7. According to international law, the determination of maritime jurisdiction areas should be carried out with mutual or multilateral agreements.

In response to escalating tensions in the East Med, Türkiye has taken preventive steps and cooperated with the TRNC and Libya in the fields of energy, defense, and security. Türkiye signed a continental shelf delimitation agreement with the TRNC in 2011. The TRNC licensed some of its maritime fields for oil and natural gas exploration.[20] Ankara signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the UN-recognized Libyan National Accord Government on the “Delimitation of Maritime Jurisdiction Areas in the Mediterranean” in 2019. Notably, Türkiye established one of the world’s leading hydrocarbon exploration fleets with seismic research and drilling capabilities for exploiting offshore energy resources in the last decade. On the other hand, the Turkish Petroleum Company was granted a license in 2020 to conduct hydrocarbon exploration and drilling activities outside Turkish territorial waters but within the continental shelf that Türkiye had declared to the UN in 2020. Simultaneously, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that the nation would continue to exercise its sovereign rights in this area.

In accordance with international law, Türkiye has declared multiple times to the UN the boundaries of its continental shelf in the East Med since 2004. More recently, on 18 March 2019, Türkiye declared that, with the longest coastline in the East Med, it has ipso facto and ab initio legal and sovereign rights in the maritime areas and demarcated the external boundaries of the Turkish continental shelf.[21] Finally, on 18 March 2020, Türkiye declared the coordinates of the outer boundaries of its continental shelf in the East Med to the UN and officially put it on record.[22] This maritime jurisdiction area is an integral part of Türkiye’s “Blue Homeland” maritime doctrine, which corresponds to Türkiye’s rights, interests and benefits in its surrounding seas. “Blue Homeland” underscores the country’s maritime sovereignty with its geographical borders including all declared and prospective maritime jurisdiction areas in the Black Sea, Aegean Sea, and the East Med, encompassing a total area of approximately 463,000 km2.[23]

As a countermove, Greece signed an EEZ delimitation agreement with Egypt on 6 August 2020. Türkiye was excluded from the process of the negotiations conducted in a secret manner, however, and notably the Greece-Egypt EEZ delimitation agreement was made after the Türkiye-Libya agreement of 2019. Even if it could be considered that Türkiye’s sensitivities were taken into consideration with the EEZ agreement in question, especially concerning the effect of the Greek island of Kastellorizo (Meis), Libya’s maritime jurisdiction areas were clearly violated.

What Happened?

2020 was a year in which Türkiye was tested with many difficulties along with the devastating COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to the social psychology of curfews and other measures and the disruption of the global logistics chain caused by the pandemic on top of the global economic crisis, Türkiye had to struggle with natural disasters, including floods and earthquakes and carry out counter-terrorism operations in its south. Concurrently, Türkiye’s steadfast support prevented the downfall of the UN-recognized government in Tripoli, Libya. Besides, Türkiye, particularly with its advanced unmanned aerial vehicles, contributed to Azerbaijan’s struggle to reclaim its occupied territory of Karabakh at the end of a 44-day war against Armenia. Azerbaijan liberated 5 cities, 4 towns, and 286 villages after 30 years of occupation, achieving its territorial integrity.

At that time, Türkiye decided to conduct hydrocarbon exploration activities with the Oruç Reis seismic research vessel in the licensed areas of the East Med in its continental shelf that was previously declared to the UN. On 21 July 2020, a Notice to Mariners (NAVTEX) announcing that Oruç Reis would be operating in the East Med met with a reaction from Greece. The Greek government spokesperson Stelya Petsas announced that the country was “ready for negotiations within the framework of international law and good neighborly relations”, and Türkiye has subsequently suspended the activities of Oruç Reis.

Meanwhile, negotiations were ongoing between the diplomats of the two countries to resume “exploratory talks” that had been on hold since 2016, and an official announcement was planned for 7 August that the exploratory talks (currently known as the consultative talks on the Aegean) would resume at the end of the month. However, at a time when negotiations based on mutual dialogue with Türkiye were going on—and while Germany, the EU Council’s then leading state, was acting as a mediator—Greece proceeded with parallel, undisclosed talks with Egypt and ultimately signed an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) agreement with Cairo on 6 August 2020. This move was perceived by Türkiye as undermining the spirit of the dialogue process.[24] Thereupon, Türkiye announced a new NAVTEX on 10 August, stating that Oruç Reis would conduct surveys in the East Med until 23 August. After this, using its naval and air forces, Greece deployed hard power measures to prevent seismic research activities in the region, which it supposedly considered as part of its own continental shelf. Nevertheless, these attempts escalated tensions in the East Med even further and brought the two countries to the brink of a hot conflict, if not a war.

Figure 2: Oruç Reis Conducts Seismic Research in the East Med (2020)

Source: Turkish Naval Forces (2020)

Henceforth, Türkiye determinedly carried out hydrocarbon exploration activities with Oruç Reis in the East Med until the end of November 2020, during which the Turkish Navy conducted maritime security operations, including escort and protection tasks, on a 24/7 basis. Meanwhile, the maneuvers performed by the Turkish frigate TCG Kemalreis, which provided escort to Oruç Reis, prevented the Greek frigate HS Limnos from intervening and pushed it away from the area. The warships chased one another, clashed, and got damaged during the tit-for-tat maneuvers at the risk of a hot conflict. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan shared in a public statement that he appreciated the determined stance of TCG Kemalreis in the area and warned the Greek leadership to refrain from further provocations.

Türkiye continued its seismic research activities in the designated area in the East Med until the mission was completed on 29 November 2020. During the geopolitical crisis between the two countries, at a critical point, Turkish warships operating in the region were deployed at 6 nautical miles of the territorial waters of the Greek island of Kastellorizo (Meis), thus giving a signal to Greece. Within the scope of Oruç Reis’s mission, a good deal of warships and naval-air assets of the Turkish Navy as well as Air Force scramble wings were deployed and kept ready in the Aegean and East Med against possible escalatory scenarios. Since the Kardak Crisis of 1996, this was the first time Türkiye and Greece came close to an armed conflict. These crises highlighted Türkiye’s effective integration of soft and hard power elements, enabling it to assert its position successfully in the East Med geopolitics—surpassing Greece on two notable occasions over the past 25 years.

Figure 3: Turkish Navy’s Sea Wolf Exercise (2024)

Source: Turkish Naval Forces (2024)

Involving diplomatic interactions and reverberations in an international setting and lasting for roughly five months from August to December 2020, the crisis encompassed the EU, the U.S., NATO, Germany, France and other international actors. A later statement by Geoffrey R. Pyatt, the then-U.S. Ambassador to Athens, revealed that the U.S. worked with Germany and France to take diplomatic initiatives and played an important role in ending the crisis.[25] Also, thanks to the mediation efforts of the then-NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg between the two allies, a military de-escalation mechanism was established for possible conflicts at sea and in the air as a result of a series of meetings held at NATO HQ in Brussels. The establishment of the agreement under the NATO Military Committee was made possible largely due to Türkiye’s constructive and resolute approach, despite instances of limited engagement and absence from some meetings on the part of the Greek side. During this period, it was observed that Greece did not want to find a military solution to the problems in the East Med under the umbrella of NATO but sought a political and diplomatic solution within the EU, which also included a pressure and sanction policy toward Türkiye.

Analysis of Strategic Communication Exchanges of the Parties

The August-December 2020 geopolitical crisis between Türkiye and Greece highlighted the critical role that strategic communication plays in shaping regional perceptions and policy. The supreme executive leaders of each nation (the President of Türkiye, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the Prime Minister of Greece, Kyriakos Mitsotakis) employed a range of communicative tools, such as speeches, press releases, interviews, official statements, and articles, to articulate each country’s stance on the East Med dispute. These exchanges not only reflected divergent policy approaches but also revealed underlying security perceptions along with diplomatic efforts.

Both governments directed their strategic communications toward distinct audiences, including but not limited to domestic constituencies, allied nations, and international organizations. Notably, both put first their domestic constituency, utilizing rhetoric directed at consolidating national support and legitimizing their foreign policy positions. While Greece had reservations [26] about the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), its statements suggested potential recourse to the ICJ for disputes on maritime jurisdiction areas, demonstrating a strategic ambiguity likely intended to further its narrative.

During this period, Türkiye and Greece used overlapping strategic communication forms, which included “Crisis communication and management”, “Reputation management”, “Public diplomacy”, “Nation branding”, “Civil-Military cooperation”, and “Military public affairs”. In addition, both sides suggested that they perceived each other as a threat. Terms like “perception management”, “propaganda”, and “hybrid warfare”, which are related to pejorative aspects of strategic communication, have been expressed in their exchanges. However, significant differences emerged in their tactical implementations. Greece employed lobbying campaigns via U.S.-based organizations (e.g., AHI, HALC) targeting the U.S. government, Capitol Hill, the Congress, ministries and academic institutions, whereas Türkiye utilized public relations to counterbalance diplomatic interactions.

It was also observed that in public discourses Greece, in particular, systematically tried to portray Türkiye as a so-called disruptive actor in the East Med by employing some pseudo-labeling terms such as “destabilizing”, “aggressive”, “problem-producing”, “provocative”, “non-compliant with international law”, and “threatening the unity of NATO”, while Türkiye countered by reaffirming its significance, self-reliance, commitments, and regional indispensability for NATO and the Euro-Atlantic Region’s security. However, findings demonstrated that Greece’s threat perception is very high, with Türkiye at the center of it. Meanwhile, both states found their own discourses consistent on the East Med.

On the other hand, in turbulent times, Türkiye did not expect any support from other countries in the international arena. On the contrary, it produced discourses about how some countries expected and demanded support from Türkiye. The code “discourses containing expectations from other countries” indicated that Greece expected support from other actors, particularly from the EU, the U.S. and France. In fact, a quantitative analysis of diplomatic outreaches and high-level engagements throughout the crisis period revealed that Greece held at least 37 meetings at the prime ministerial level with the leaders of 13 different regional and global actors regarding the East Med. Türkiye held eight presidential-level meetings with five actors, reflecting the stark contrast compared to Greece. It was regarded as a matter of common sense and an autonomy-driven approach on Türkiye’s behalf.

Greece’s approach, marked by efforts to garner support and advocate for sanctions—particularly within the EU—stood in contrast to Türkiye’s responsive diplomacy, which focused on countering restrictive measures and promoting dialogue. Athens also accelerated defense modernization efforts, increasing defense expenditure by 44% for 2021 and purchasing sophisticated platforms and weapons (such as Belharra frigates, Rafale and (prospective) F-35 aircraft) from France and the U.S., intended partly to undertake deterrence. Despite Greece’s intensive lobbying, the EU declined to impose serious sanctions on Türkiye and opted for dialogue facilitation, which was a German-mediated choice. The conclusions of the EU Council summit held on 11-12 December 2020 emphasized that the EU-Türkiye interaction would be maintained, the “positive agenda” on cooperation on migration issues and economic relations would be focused on, and direct exploratory talks between Athens and Ankara would smoothly be continued.[27] This outcome highlighted the limited effectiveness of Greece’s strategic communication efforts within the EU. In response, Athens chose to rapidly finalize defense agreements with France and the U.S. in 2021, which represented a shift toward hard power security guarantees in the domain of diplomatic setbacks.[28]

This research revealed that Türkiye pursued a more independent East Med policy with confidence, with a faster decision-making process, while Greece relied on its partners, such as France, the EU, and the U.S., to pursue an external actor-dependent policy, such as attempting to persuade many states through shuttle diplomacy. It was observed that in the face of potential geopolitical tensions with Türkiye, Greece promptly adopted a contingency-driven approach, activating a series of responsive policy measures. In brief, Greece’s responses were as follows:

- Intensifying its diplomatic efforts to transpose bilateral issues between Türkiye and Greece onto the EU, alarming Brussels to pledge itself by taking sides with Greece in defense against a common adversary, ensuring that the EU exerts political pressure over Türkiye and takes an embargo decision within the Council consisting of various political, military and economic sanctions.

- Convincing the Greek parliament and people of the urgent need for armament and modernization of the armed forces with new warships, aircraft, armored vehicles, long-range and offensive weapons and missiles and other combat vehicles, material and supplies from abroad.

- Mobilizing the U.S. and France as its strategic partners and procuring cutting-edge technologies and weapons from these countries, granting them privileges including new bases and ports in return.

- Forcing its strategic partners to step into the field in the Aegean Sea and the Mediterranean to conduct joint exercises at sea, on land and in the air, and to take a stance in the region in favor of Greece to create a purported deterrence against Türkiye.

- Shaping national and international public opinion with the anti-Türkiye perception that might gain ground by intensifying propaganda and disinformation activities.

- Initiating a diplomatic campaign in the international arena, with target audiences including heads of state/government, foreign ministers, high-level officials, international media organizations, and opinion leaders of other states through bilateral or multilateral in-person and video conference meetings, employing public diplomacy, complaint diplomacy, disinformation, perception management and other methods to discredit Türkiye, thus leading the international community to take a position against Turkish moves and arguments and put political and diplomatic pressure on Türkiye.

- Drawing in players such as the EU, NATO or Germany, the role of an intermediary that can play a mediator role with Türkiye to lower tensions, keep Türkiye at the negotiating table, and mold the geopolitical environment in line with its own interest.

The fact that the policies and narratives of the parties on the Aegean Sea and East Med issues, especially the Cyprus issue, maritime jurisdiction areas, and illegal immigration, differ and are mostly contradictory to each other reinstates the present stalemate and deep-rooted disagreements. Notably, Greece has shown the capacity to utilize a range of strategic communication tools during periods of tension, including diplomatic outreach, perception management, lobbying efforts, and, at times, the dissemination of unverified claims.

Conclusion

This study examined the East Med geopolitics by analyzing the competing narratives of Türkiye and Greece, alongside the roles of key regional and global actors, geopolitical dynamics, and strategic communication exchanges in the region. Through a comprehensive discussion of geopolitics and the involved parties’ approaches, particularly concerning maritime boundaries, hydrocarbon resources, and claims of sovereignty, the research highlights the intricate interplay of national interests and power politics. The East Med remains a highly contested geopolitical space, with Türkiye and Greece at the center of it. The findings demonstrate how strategic communication plays an effective role in turbulent times and underscore the necessity of constructive policy approaches.

As a sui generis maritime space, the Mediterranean serves as a crucial fulcrum between Africa, Europe, and Asia, holding geostrategic significance for global trade, energy transit, and freedom of navigation. Strategic choke points, including the Turkish Straits, are vital for maritime security and international commerce. Recent discoveries of hydrocarbon reserves attracted the attention of global actors to the East Med, leading to increased geopolitical tensions, particularly over maritime boundaries and the sharing of energy resources.

The 21st century has introduced heightened instability due to regional conflicts, shifting security paradigms, and the reverberations of great-power competition. In the wake of today’s frozen issues, crises, and conflicts in MENA and the East Med, it is possible to assert that behind-the-scenes geopolitics stem from the interventionist and skewed policies that global powers adopt so that they can advance their influence in the region, control regional dynamics, and maximize their interests.

Despite being NATO allies, Türkiye and Greece have experienced fluctuating relations, with a graphic of ups and downs, due to historical grievances and conflicting strategic interests. A range of unresolved disputes—particularly concerning sovereignty and maritime jurisdiction in the East Med and the Aegean Sea—continues to spark periodic tensions between the two countries. As long as expansionist tendencies in Greece persist, reaching a comprehensive, fair, and lasting resolution to the complex issues between the two countries may remain challenging. As a regional power, Türkiye has shown the ability to effectively integrate hard and soft power while contributing meaningfully to regional and global peace and security.

Strategic communication focuses on creating effects and changes in the cognitive field. In essence, it can play a pivotal role in fostering mutual understanding, developing good relationships, and building an enduring trust in international relations. However, in geopolitical competition, discourse alone does not have the power to alter realities; success depends on a nation’s capability to leverage strategic communication alongside tangible power instruments. Both Türkiye and Greece employ robust military postures and substantial expenditures to reinforce deterrence and advance their strategic objectives. Nevertheless, lasting stability in the East Med can only be achieved through sustained diplomacy, adherence to international law, and a commitment to cooperative solutions. A shift from confrontation to collaboration could transform the Aegean into a “sea of peace”, fostering the entire region’s security and prosperity.[29]

As Atatürk once stated, “The supreme interests of Türkiye and Greece no longer conflict; both nations should recognize that security and strength lie in a sincere friendship.”[30] Under his visionary leadership as a milestone, Turkish Prime Minister İsmet İnönü and Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos signed the Ankara Friendship Agreement in 1930, which established a foundation for confidence and trust. More recently, the 2023 Athens Declaration on Friendly Relations and Good Neighborliness between Türkiye and Greece emerged as a promising development and marked the beginning of a new détente era. The peoples of both nations remain hopeful that dialogue and diplomacy will prevail, turning this historic opportunity into an ultimate resolution and lasting peace.

References

[1] Manuel Borutta, “Mediterraneum,” in European History Online, (Mainz: Leibniz Institute of European History, 2021), https://www.ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/crossroads/border-regions/manuel-borutta-mediterraneum. (Accessed March 11, 2025).

[2] National Maritime Historical Society, https://seahistory.org/sea-history-for-kids/to-sail-the-seven-seas/. (Accessed March 17, 2025).

[3] James Stavridis, Deniz Gücü: Okyanusların Tarihi ve Jeopolitik Önemi, (Çev. Nil Tuna, Varol Ataman), Epsilon Yayınevi, İstanbul, 2021 p. 165.

[4] UN Environment Programme, “Maritime transport,” https://www.medqsr.org/maritime-transport/. (Accessed March 11, 2025).

[5] The UK was included due to its overseas territory in the Mediterranean; Gibraltar, and its bases, Akrotiri and Dhekelia located at the south of the island of Cyprus.

[6] 5 GRID-Arendal (A non-profit environmental communications centre based in Norway), https://www.grida.no/resources/5900. (Accessed March 11, 2025).

[7] Fernand Braudel, Akdeniz ve Akdeniz Dünyası (La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen à l’époque de Philippe II), (Cilt-1) (Çev. Mehmet Ali Kılıçbay), Eren Yayıncılık, İstanbul, 1989, pp. 58, 59.

[8] International Hydrographic Organization, Limits of Oceans and Seas, (Special Publication N°.23), Imp. Monegasque, Monte Carlo, 1953, Feuille 2, p. 15, 44.

[9] U.S. Navy Chief of Naval Operations Navigation Plan 2022, p. 3.

[10] “Gaza War ‘Tragedy for Humanity’: China” The Daily Guardian, March 8, 2024, https://thedailyguardian.com/europe/gaza-war-tragedy-for-humanity-china/. (Accessed March 17, 2025).

[11] J. Stavridis, 2021, p. 128.

[12] George Friedman, “Making Sense of Turkey,” Geopolitical Futures, May 17, 2016, https://geopoliticalfutures.com/making-sense-of-turkey/. (Accessed March 21, 2025).

[13] “AHI President Attends Archons’ 4th Annual International Religious Freedom Conference; Sponsors Defense Policy Briefing,” American Hellenic Institute, June 7, 2024, https://americanhellenicinstitute.org/press-releases/defense-policy-briefing-athens-2024-archon. (Accessed June 17, 2024).

[14] Tullio Treves and Laura Pineschi, The Law of the Sea: The European Union and Its Member States (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1997), p. 226.

[15] Mustafa Balbay, “How did Greece grow seven times?” Cumhuriyet, September 3, 2020, https://www.cumhuriyet.com.tr/yazarlar/mustafa-balbay/yunanistan-yedi-kez-nasil-buyudu-1763028. (Accessed March 18, 2025).

[16] “Explore All Countries—Greece,” The World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/greece. (Accessed March 7, 2025).

[17] U.S. Geological Survey, Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of the Levant Basin Province, Eastern Mediterranean, 2010.

[18] U.S. Geological Survey, Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of the Nile Delta Basin Province, Eastern Mediterranean, 2010.

[19] U.S. Geological Survey, National and Global Petroleum Assessment, Assessment of Undiscovered Conventional Oil and Gas Resources in the Eastern Mediterranean Area, 2020.

[20] Emete Gözügüzelli, “Doğu Akdeniz’de Türkiye-GKRY Arasındaki İhtilafın Boyutları”, 7 Mayıs 7, 2018, Marine Deal News, https://www.marinedealnews.com/dogu-akdenizde-turkiye-gkry-arasindaki-ihtilafin-boyutlari/ (Accessed March 18, 2025).

[21] UN General Assembly A/73/804, Letter dated 18 March 2019 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General.

[22] U.N. General Assembly, A/74/757, Letter dated 18 March 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General.

[23] Serhat Süha Çubukçuoğlu, Turkey’s Naval Activism Maritime Geopolitics and the Blue Homeland Concept, (eBook) Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, Switzerland, 2023, p. 3.

[24] Republic of Türkiye MFA, Joint Press Conference, 25 August 2020, Ankara, https://www.mfa.gov.tr/disisleri-bakani-sayin-mevlut-cavusoglu-nun-almanya-db-ile-ortak-basin-toplantisi-25-agustos-2020.tr.mfa (Accessed March 13, 2025).

[25] U.S. Embassy in Greece, Speeches and Interviews by Former U.S. Ambassador to Greece Geoffrey R. Pyatt, https://gr.usembassy.gov/ambassador-pyatts-remarks-at-the-center-for-european-policy-analysis-panel-changing-tides-great-power-competition-in-the-eastern-mediterranean/ (Accessed April 29, 2024).

[26] International Court of Justice, Declarations recognizing the jurisdiction of the Court as compulsory, Greece, 14 January 2015, https://www.icj-cij.org/declarations/gr (Accessed April 11, 2025).

[27] European Council, “European Council conclusions, 10-11 December 2020,” https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/12/11/european-council-conclusions-10-11-december-2020/ (Accessed March 13, 2025).

[28] “Strategic Partnership for Defence and Security Cooperation Agreement” with France on 28 September 2021 and “Mutual Defence Cooperation Agreement (MDCA)” with the USA on 14 October 2021.

[29] Nazif Bozkurt, Doğu Akdeniz Jeopolitiğinde Türkiye ve Yunanistan, Ati Yayınevi, İstanbul, 2024, p. 388-391.

[30] Zafer Çakmak, “Venizelos’un Atatürk’ü Nobel Barış Ödülü’ne Aday Göstermesi”, Erdem: İnsan ve Toplum Bilimleri Dergisi, 2008, Sayı 52, pp. 91-110.