Industries go where states do not; thus, from procurement tools for military modernization to engineers transforming the defense community, public-private partnerships (PPPs) between institutions and industry drive internal innovations within the defense ecosystem. These innovations aim to strengthen the defense’s adaptability, capability and sustainability by revolutionizing its institutions, governance, and performance. This revolution, fueled by knowledge flows, provides defense strategists with solutions to uncertainty by shifting focus from one situation to another in favor of the most concerning one by multiplying the number of options available.

The debate over defense preparedness and resilience in Washington and Brussels highlights the interconnected geopolitical environment and security agendas that necessitate a transformation in defense [1]. The 2022 National Defense Strategy (NDS), the 2022 National Security Strategy (NSS), the 2023 National Defense Industrial Strategy (NDIS) [2], the 2024 Reports from Draghi and Niinistö (Sept 2024), and the 2025 EU White Paper for Defense [3] confirm that the future of defense transformation lies with public-private partnerships (PPPs), since the infrastructure they build enables the defense to achieve both its short- and long-term objectives. In light of this, to comprehend how PPPs enhance the strategic decision-making of defense institutions, it is essential to view them within the framework of a knowledge ecosystem, which guarantees both strategic and military advantage.

While much is known about PPPs as architects of technological innovations, there is a limited understanding of their role as drivers of defense transformations. The nature of these transformations has significant implications on a) how defense organizations learn and adopt innovation to subvert and avert complex challenges and b) what processes defense organizations go through to maintain the superiority they enjoy.

Between economic pragmatism and strategic pragmatism

In 2022, the aggregate value of public-private partnership transactions that reached financial close in the European market totaled €9.8 billion, a 17% increase from 2021 (€8.4 billion) [4]. Within this growth, defense is the second largest sector, with €1.5 billion. Three large transactions in Türkiye, France and Cyprus, were closed in the defense sector, aggregating the value of €4.25 billion, representing 44% of the total market value (compared to 45% in 2021) [5]. Besides usual engagements in defense such as transport and equipment, public-private collaborations supervise and govern a number of other areas. Whether it is the protection of critical energetic infrastructures in the East Mediterranean [6], the reinforcement of cyberspatialities through military training in operational energy [7], the conceptualization of a proactive operational framework for the undersea-space warfare dimension [8] or the establishment of corporate universities [9], PPPs enable defense organizations to learn how to change to ensure their superiority. Providing intelligence on the state’s capacity to sustain a conventional fight over an extended period, this superiority would serve as a deterrent to the state’s adversaries.

While the war in Ukraine is changing global alliances, the U.S.-China trade war is creating a new global order in which countries, according to the Amundi report [10], are positioning themselves to capitalize on the competition between global powers to amplify their strategic and commercial goals. Using a public-private partnership approach, countries like Australia and Singapore are increasingly gaining geopolitical influence, benefiting from resource and supply chain diversification, and new defense agreements by approaching the adoption of Revolution Military Affairs-style information to acquire a ‘knowledge edge’ in warfare [11]. Likewise, the EU applies its sui generis defense policy in military packages. These packages are conceptualized and executed through a PPP framework under the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PeSCo), with a two-fold purpose: to provide the EU with a clear roadmap on military ability and to reinforce the EU integration logic [12]. Furthermore, the NATO 2030 Agenda recognized the importance of training and mentoring platforms with industry actors to ensure the collective defense of its members and to maintain the Alliance’s strategic edge [13]. Its two major initiatives launched at the Madrid Summit in 2022, namely the Defense Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic (DIANA) and the NATO Innovation Fund (NIF), illustrate a clear refocusing on PPPs involving defense industry actors to increase awareness, adopt and assign new responsibilities, and creatively tap into experience and knowledge [14].

Overall, PPPs play a crucial role in addressing the economic and strategic needs of defense organizations. At the same time, driven by technological development and innovation, PPPs have reinvented the institutional culture and governance methods of defense policy [15]. By doing so, they help model the national defense innovation ecosystems, which can vary significantly between domestic and international contexts. However, successful transformation also hinges on understanding the values and concerns of all stakeholders involved. Ultimately, it’s about connecting investments in national security to enhanced competitiveness and smarter technology investments [16].

Public-Private Ecosystems

The term “ecosystem,” coined by the British botanist Arthur Tansley in the 1930s, was first applied to the business world by James Moore, a strategist, in the early 1990s, considering its ability to quickly adapt to new challenges and exploit new opportunities by leveraging a wide range of capabilities [17]. Yet, adaptation, exploitation and management of capabilities leverage the knowledge of the human capital. Ideas in an ecosystem are curated, disseminated, and standardized through knowledge management activities. It implies a transformation of the ways of working about innovation in all industrial sectors, for private and public actors. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), as a successful example of a Public-Private Ecosystem (PPE) in defense [18], is responsible for creating breakthrough technologies and capabilities for national security.

Since its founding in 1958, DARPA has supported multidisciplinary expertise, creating an ecosystem of innovators from the public and the private sectors that both compete and cooperate with each other [19]. This public-private ecosystem’s ability to anticipate and respond to critical situations through projects such as the DARPA Challenge (self-driving cars) and In the Moment (AI-PPPs) is explained by the transformation of information into knowledge as a necessity of the U.S. Defense to learn anticipatorily about the strategic surprises that surrounded the U.S. and its Allies from 1958 until today [20]. Besides, the DARPA’s successful model of bottom-up governance lies with its knowledge workers—the program managers—who are given complete autonomy to identify and perform projects of relevance to the military needs. These knowledge workers must learn about the present and potential risks, identify technologies and processes to mitigate them and cultivate the next generation of knowledge workers [21]., such as in the case of Axon Ventures Capital in Israel. Founded by alumni of Talpiot, the elite IDF military training program, the company supports start-ups from Talpiot graduates [22]. Here, the consciousness element steers the venture capital activity. This way, Axon VC ensures that talent does not drain and that the best technologies remain in the country and at the service of defense.

At the same time, leveraging learning through an organization, Axon VC shows that visionary leadership inspires innovative behavior. The advent of Web 2.0 in the early 2000s was the big innovation that drove many changes in the character of warfare. Integrating IT technologies and then AI systems into existing conventional weapons and systems gave rise to important questions that discuss the survival of the Western strategic edge in the face of China or Iran, which are driving their own Revolution in Military Affairs ( RMA )[23]. Moreover, with the inclination toward dual-use technologies, advanced military-industrial sectors seem no longer the primary drivers of technological innovation. Accordingly, the main question is how will the diffusion of disruptive technologies impact defense superiority and its governance? Answers will most probably be shaped by the PPE’s diversity of stakeholders, supportive infrastructure [24], funding, regulatory frameworks and a culture of innovation [25].

Creating Value through Knowledge

PPEs create value for defense’s competitiveness through knowledge management in four ways. First, as system integrators placed within the defense ecosystem, the partnerships are responsible for bringing together borderless expertise for identifying intersections between civilian and military needs, which adds to the policy’s competitiveness. Second, they induce institutional proliferation within defense institutions to make them more resilient. Third, PPEs are guiding defense toward future-oriented thinking and, as a result, toward anticipatory governance—equipping decisional structures to learn, prepare, recognize and manage future challenges. Fourth, they define the model of the defense innovation ecosystem.

As system integrators, PPEs are increasingly engaging in activities outside their perimeter. Their core business is integrating components, skills, and knowledge from experts, end-users, institutions, competitors, and academia to produce more complex products and services [26]. Through harnessing specialized knowledge processes, PPP brings together people with varied skills to work effectively on the transformation for the strategic edge of the defense establishment through cross-project learning. The Leonardo Cyber Academy is a case in point, which provides defense institutions and various other stakeholders with a comprehensive strategy and solutions addressing organizational and technological challenges. The Academy benefits from Leonardo’s extensive knowledge in the physical and cyber protection of critical infrastructure across more than 150 countries worldwide, including services for 75 sites in 29 NATO countries [27].

The growth of institutional agencies and policies stems from the systematic operations within the PPE framework in the defense sector. In difficult times for community-focused initiatives, the EU proliferates new agencies. At the time when PeSCo was created, in 2007, no extreme security exigencies would lead Europeans to consider security independence: NATO was still the obvious choice no matter the ups and downs of the transatlantic relationship. The clock was ticking for Europe in 2016 when the EU Global Strategy called for upgraded cooperation in security and defense from a ‘shared vision to common action’. PeSCo signifies an innovative multinational defense strategy, carefully designed and implemented through a cooperative alliance between government and industry [28]. The management of PeSCo functions on two separate levels, specifically at the Council level and within the context of public-private projects at EDA’s level [29]. The initial strategy focuses on utilizing EU and member state resources to promote gradual multinational technological advancements that improve current capabilities, similar to the ‘reinforce’ aspect described in the Joint Communication. The next step focuses on leveraging private investment to propel innovation in EU defense while assisting member states in maximizing resources and enhancing capabilities [30].

The future of defense decision-making lies with anticipatory governance, considering the insecurity agenda’s expansion with less predictable challenges and less well-understood actors. Thus, national and transnational defense establishments are investing in anticipatory capabilities for self-defense and military effectiveness. One emerging investment is Artificial Intelligence (AI) with military applications, which aims at integrating AI into the collaborative platforms between public sectors and defense industries. AI complements human decision-making by providing, thus, an early warning and holistic approach to future crises [31]. That’s precisely in the context of the Memorandum of Understanding between the European Commission and the stakeholder associations in 2021 representing AI, data, and robotics [32]. The memorandum manifests Brussels’ institutional intentions to bring together trusted human and AI decision-makers to align decisions and generate problem-solving tools in a crisis scenario.

Since war is a human venture, human capital is decisive to existing and innovative operational frameworks in the battlefield. To build that human capital, state and industry are increasingly leveraging networks and assets within the PPE to support individual and organizational learning through unlimited opportunities to build foresight skills through mentorship, innovative technology, and first-class learning resources [33]. This logic drives the scenarios in The future conflicts 2030-2060 [34], a publication commissioned in 2022 by the French Ministry of Armament, which engaged this special unit within the Innovation Agency, Ministry of Defense, to design those war scenarios that would potentially threaten France in 2060. This publication suggests that with the new methodologies and approaches to strategic thinking, both the private and public sectors have pragmatic and ethical concerns toward the establishment and efficiency of anticipatory governance in defense [35].

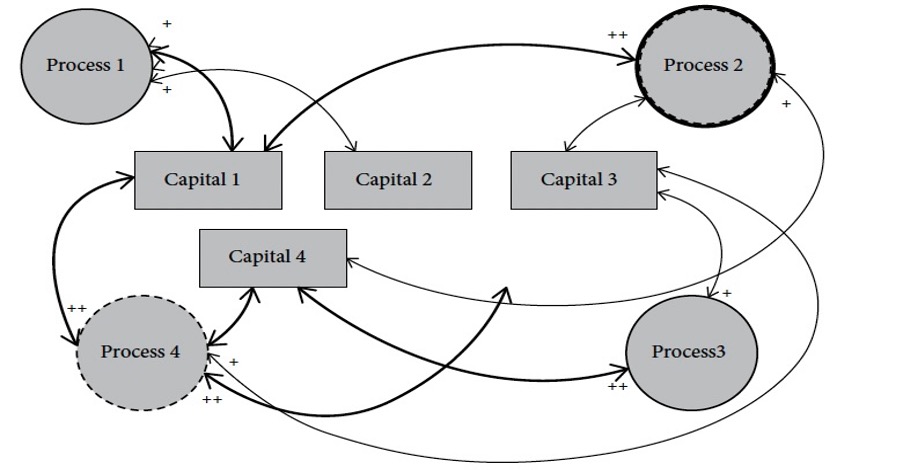

PPPs, by pooling their resources and capabilities, shape the national defense innovation ecosystems. To understand how and through which processes PPEs do this, a potential approach would be to gather empirical data about the biggest defense innovators or spenders on innovation performance, innovation ratio, innovation readiness, performance of defense industries, strategic contexts, culture of innovation and institutional environment. The information gathered from these indicators helps to understand the knowledge capital and knowledge processes that map the defense innovation ecosystem, as illustrated in Figure 1. While knowledge capital refers to knowledge stock or fixed assets, knowledge processes are the information flows that feed into the stocks. Knowledge capital would be anything starting from networks, governance infrastructure, entrepreneurial culture—among many other factors. The knowledge processes would be any field-oriented activity such as innovation diplomacy, civil-military cooperation, and corporate universities.

Figure 1: Example of defense innovation ecosystem mapped by PPEs

Source: Author 2024

Part of the solution or part of the problem?

The full immersion of the industry into the life of the defense establishments has generated innovation hubs, agencies, centers of excellence, accelerators and test centers with a threefold purpose: a) to help bridge the technology innovation gap between industry and the military b) to create a collaborative governance of interdependent actors able to address complex problems, and c) integrate national markets and incentivize common procurement among states with the same strategic interests. PPEs seek to understand how to help the defense ecosystem build its own strategic edge through policymaking and defense planning.

In terms of policy planning, public-private partnerships are introducing a ‘responsible defense governance’ [36]. While this concept establishes standards and develops best practices on how defense institutions can be responsibly governed, this analysis’s understanding goes beyond that, focusing on the authority aspects and how they are viewed in the national defense strategy. National defense strategies devote attention to the importance of the relationship between the industry, the political and the military. While entering the underwater-airspace warfare, policymakers see partnerships as the right tool to make ends and means meet. The industry might not always be interested in designing a project that matches the institutional budget. Rather one that is able to address complex issues. Related to this, besides the various ‘grammars’ used to identify PPPs such as projects, contracts, tools, and system integrators, the last one assigned to partnerships, is ‘the innovators’ because of their knowledge potential. Institutional attention, therefore, seems ultimately directed toward innovators, which ultimately leads to a transformation in national defense strategies from one authority to multiple authorities. The situation also becomes serious when these multiple authorities are required to decide upon the strategic direction of defense policy. PPPs are required to maintain and promote a high degree of coordination in that regard. There might be cases when the industry’s proposals are not in line with the strategic concept, yet the industry urges the institutions to consider an alternative opportunity that benefits them in the future. This raises the question of which agencies and structures the institutions should plan to manage that project.

Defense planning, either at the tactical, operational or strategic level, should be able to deliver the promised capabilities. It should also be able to adjust to unexpected situations/crises. While it is common knowledge that there is overt capability support from NATO allies to Ukraine, it is less known whether this support was planned in advance or not [37]. Effective defense planning requires institutionalization of PPE’s role and its functioning procedures, which might be negatively impacted by the rising cost of military innovation and budgetary pressures at the national level [38].

Conclusions

Defense policy communicates its vision frequently, aligning it with the process of transformation. This paper, reflecting on the PPP’s contribution to the strategic advantage in defense, observes how defense governance has reached a point where PPPs are both opportunistic entrepreneurs and decision-makers. The nature/context of the defense industry is critical to the corresponding defense organization in several ways. First, pooling and sharing expertise among decision-makers and industry actors contributes to the epistemic capital of the specific defense organization. This guides decisions about what solutions should be adopted to mitigate current and future threats. Second, partnering with specific institutions allows different sectors of the industry to contribute to the political sphere of defense because of the institution’s need for technology and expertise from the industry, as discussed in the study. Third, cooperation between different leaderships helps both sides of the partnership to bolster their competencies by engaging in continuous learning and interpretation.

Fourth, as mentioned in our discussion, PPPs have been upgraded to a knowledge management ecosystem in which expertise is applied to strengthen defense capabilities in identifying threats early on and crafting adequate responses through the integration of new technologies. Determining what such responses could be involved in this regard is therefore essential to the defense organization’s vision. The empirical account showed how public-private partnerships broaden our understanding of the process of organizational innovation in defense and why it matters for defense organizations to keep their strategic and thus technological edge.

By driving innovation through expert knowledge, PPPs not only have assumed a new role as governance entrepreneurs, but studying their activity is important to understand major changes in strategies, technologies, organizational structures, and doctrines and their impacts on both the domestic defense community and the international environment. In conclusion, much more research is needed on organizational innovation in defense, especially in light of AI’s development and its integration into the RMA. The topic of PPE and Organizational Innovation (OI) is especially relevant as we develop and strengthen the state defense strategies of the future. Defense organizations will not stop innovating as they seek to ensure their competitiveness, resilience, and sustainability. New policies, actors, resources, and interests will emerge to pursue these objectives urgently, always relying on knowledge as the key tool, as this research has shown. Meanwhile, PPEs connect power dynamics, information, structures, and resources to achieve organizational change. Therefore, future research needs to focus more on how PPE’s interest in developing innovative capabilities is influenced by PPE’s ability to shape the defense organization itself.

Endnotes

[1] Emanuele Bonini, “White Paper on Defense identifies Russia and China as possible EU enemies,” EUNews, March 14, 2025, https://www.eunews.it/en/2025/03/14/white-paper-on-defense-identifies-russia-and-china-as-possible-eu-enemies/.

[2] US Department of Defense, 2022 National Defense Strategy, Washington, October 27, 2022,

https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.pdf.;

The Whitehouse, National Security Strategy, Washington, October 2022.

[3] Sauli Niinistö, “Safer Together Strengthening Europe’s Civilian and Military Preparedness and Readiness,” European Commission, 2024.; Mario Draghi, “The future of European competitiveness,” 2024, Part A | A competitiveness strategy for Europe. Brussels: European Commission; And European Commission March 24, 2025.; Joint White Paper for European Defence Readiness 2030, https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/document/download/30b50d2c-49aa-4250-9ca6-27a0347cf009_en?filename=White%20Paper.pdf., Retrieved March 27, 2025.

[4] European Investment Bank, “Market update Review of the European public-private partnership market in 2022,” European PPP Expertise Centre, March 2023.

[5] Ibid. 4

[6] Erwan Lannon, “EU Cybersecurity Capacity Building in the Mediterranean and the Middle East,” IE Med., 2019, https://www.iemed.org/publication/eu-cybersecurity-capacity-building-in-the-mediterranean-and-the-middle-east/.

[7] “The critical role of operational energy in military readiness and resilience,” The Atlantic Council, February 27, 2025,

[8] Joe Saballa, “Fincantieri Begins Production of Italy’s Next-Gen Submarine,” The Defense Post, January 14, 2022, https://thedefensepost.com/2022/01/14/fincantieri-italy-submarine/.

[9] Mark Allen, “Expanding the Value of Corporate Universities: The Stakeholder Approach,” In Aldo Romano and Giustina Secundo (Eds.), Dynamic Learning Networks: Models and Cases in Action (London: Springer, 2009): pp.121-136.

[10] “Geopolitics,” Amundi Institute, June 2023, https://research-center.amundi.com/files/nuxeo/dl/3df6c9a7-9e25-4968-b38c-66907f8cd40c?inline=.

[11] Low Hong Kuan, “Public-Private Partnerships In Defense Acquisition Programs—Defensible?,” Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California, December 2009.

[12] “A Strategic Compass For The EU,” EEAS, Retrieved April 30, 2023, from https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/strategic-compass-security-and-defence-1_en#:~:text=The%20Strategic%20Compass%20was%20adopted,security%20and%20defence%20into%20reality.

[13] “NATO 2030: United for a New Era,” NATO, November 25, 2020, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2020/12/pdf/201201-Reflection-Group-Final-Report-Uni.pdf., Retrieved January 16, 2021.

[14] Daniel Fiott, “The EU, NATO and the European defence market: do institutional responses to defence globalisation matter?” European Security 26, no. 3 (2017): pp. 398-414. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2017.1352582.

[15] Phil Budden and Fiona Murray, Defense Innovation Report: Applying MIT’s Innovation Ecosystem & Stakeholder Approach to Innovation in Defense on a Country-by-Country Basis, Massachutes Institute of Technology (MIT), May 2019,; Susan Grajek and D. Christopher Brooks, “A Grand Strategy for Grand Challenges: A New Approach through Digital Transformation.,” Educause Review, August 10, 2020, https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/8/a-grand-strategy-for-grand-challenges–a-new-approach-through-digital-transformation.

[16] William B. Rose, Transforming Public-Private Ecosystems: Understanding and Enabling Innovation in Complex Systems (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022): see p. 19.

[17] François Candelon, Herald Rubner, Hans-Paul Bürkner, Ulrich Pidun, Balázs Zoletnik, and Anna Schwarz, “How Public-Private Ecosystems Can Help Solve Societal Problems,” BCG, February 4, 2022, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2022/how-can-public-private-ecosystems-help-societal-problems.

[18] Hayley Channer, “Improving Public-Private Partnerships on Undersea Cables: Lessons from Australia and Its Partners in the Indo-Pacific,” Indo-Pacific Outlook 1, no. 2 (January 17, 2024), https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/10f6cf7f-1982-4c26-8acb-7cf7f08b352c/content.

[19] William B. Bonvillian, Richard Van Atta, and Patrick Windham (Eds), The DARPA Model for Transformative Technologies: Perspectives on the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, Open Book Publishers, 2019, p. 20

[20] Patrick Windham and Richard Van Atta, “Introduction,” In William B. Bonvillian, Richard Van Atta, and Patrick Windham, The DARPA Model for Transformative Technologies, Open Book Publishers, 2019, pp. 1-26.

[21] Erica R.H. Fuchs, “Cloning DARPA Successfully,” Issues in Science and Technology 26, no. 1 (2009): pp. 65-70, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43315003.

[22] “About us,” Axon VC, 2019, https://www.axon.vc., Retrieved December 7, 2022.

[23] Michael Raska, “The sixth RMA wave: Disruption in Military Affairs?,” In Defence Innovation and the 4th Industrial Revolution (Routledge, 2022).

[24] “Japan unveils record defence budget amid regional security fears,” Al Jazeera, December 23, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/12/23/japan-unveils-record-defence-budget-amid-regional-security-fears.

[25] Andrew Hill, “Military Innovation and Military Culture,” The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters 45, no. 1 (2015): 85-98. doi:10.55540/0031-1723.2809; Christian Guetl and Vanessa Chang, “Ecosystem-based Theoretical Models for Learning in Environments of the 21st Century,” International Journal of Emerging Technologies in learning 3 (2008): pp. 50-60, https://online-journals.org/index.php/i-jet/article/view/742; Jason C. Moyer, Henri Winberg, “Sweden’s Contributions to NATO: Bolstering the Alliance’s Defense Industry and Air Capabilities,” Wilson Center, January 23, 2024, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/swedens-contributions-nato-bolstering-alliances-defense-industry-and-air-capabilities., Retrieved May 16, 2024.

[26] Valérie Merindol and David W. Versailles, The (R)evolution of Defence Innovation Models: Rationales and Consequences. IRIS Nr.60 (2020): pp. 1-27.

[27] Cyber Academy, Leonardo, 2022, https://cyberacademy.leonardo.com/en/home., Retrieved December 5, 2022.

[28] “Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe,” EEAS, 2016, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eugs_review_web_0.pdf.; European Commission, “Action Plan on military mobility: EU takes steps towards a Defence Union,” March 28, 2018.

[29] Council of the European Union, “Decision 2018/909 establishing a common set of governance rules for PESCO projects,” Official Journal of the European Union, June 26, 2018, pp. 37–41.

[30] Simon Sweeny and Neil Winn, N. (2022). “Understanding the ambition in the EU’s Strategic Compass: a case for optimism at last?,” Defence Studies 22, no. 2 (2022): pp. 192-210, https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2022.2036608.

[31] M. Pengili and T. Santos, Overcoming challenges to defence decision-making in times of crisis: the AI-Public Private Partnership and the Anticipatory Governance, Solna: ICES Conference 2023.

[32] “The New Public Private Partnership: AI, Data, and Robotics,” EUnited, May 2021, https://www.eu-nited.net/eunited+aisbl/robotics/news/the-new-public-private-partnership-ai-data-and-robotics.html., Retrieved February 12, 2023; “Developing Algorithms that Make Decisions Aligned with Human Experts,” DARPA, March 3, 2022, https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2022-03-03., Retrieved February 12, 2023.

[33] Spark your curiosity: Our information technology teams are global innovators,” BAE Systems (n.d.), https://www.baesystems.com/en/careers/careers-in-the-uk/experienced-professionals/information-technology.

[34] Red Team Défense, Ces Guerres Qui Nous Attendent, 2030-2060 (1st edn ed.), Paris: PSL Équateurs, 2022.

[35] (2023, March 21). Les Futures Possibles du Management Public -Edition 2024, Panthéon-Assas Université, March 21, 2023, symposium-managementpublic.com, https://www.symposium-managementpublic.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Appel-a-communication_Symposium-ADIMAP_doc-complet-2023.pdf.

[36] “Responsible Defence Governance,” Transparency International (nd)., https://ti-defence.org/what-we-do/responsible-defence-governance/., Retrieved June 25, 2023.

[37] “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept,” NATO, 2022, https://www.nato.int/strategic-concept/., Retrieved January 25, 2024.

[38] Marina Favaro, Ulrich Kühn, and Neil C. Renic, “Will DIANA—NATO’s DARPA-style innovation hub—improve or degrade global stability?,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March 23, 2023, https://thebulletin.org/2023/03/will-diana-natos-darpa-style-innovation-hub-improve-or-degrade-global-stability/., Retrieved April 12, 2024.