1. Introduction

Cryptocurrencies are widely used worldwide, and at the end of 2024, there were more than 560 million crypto users, which represents around 6.9% of the overall world population. Among the countries, there were significant differences in the usage of cryptocurrencies, and the list of the ten top countries for crypto usage is quite interesting (see Table 1).

Table 1: Top 10 countries for Cryptocurrency usage

| Country | Population (mln) | No. of users of cryptocurrencies (mln) | Percentage of population using cryptocurrencies |

| United Arab Emirates | 11.0 | 2.8 | 25.3% |

| Singapore | 5.8 | 1.4 | 24.4% |

| Turkey | 87.4 | 16.9 | 19.3% |

| Argentina | 45.6 | 8.6 | 18.9% |

| Thailand | 71.7 | 12.6 | 17.6% |

| Brazil | 212.0 | 37.1 | 17.5% |

| Vietnam | 101.0 | 17.6 | 17.4% |

| United States | 345.4 | 53.5 | 15.5% |

| Saudi Arabia | 34.0 | 5.1 | 15.0% |

| Malaysia | 35.6 | 5.1 | 14.3% |

Source: Triple A and United Nations Population Division data processed by the author

The new payment methods based on blockchain technology are widely used in both developed and developing economies, and the income or the size of the country is not the only driver that matters for using the new type of money. Central Banks and governments have a strong interest in creating their own cryptocurrency to avoid the risk of losing control of the money supply due to the strong supply of new payment solutions based on crypto-assets offered by private marketplaces.

Central Bank Digital Currencies (hereinafter CBDC) are cryptocurrencies that must be accepted if offered in payment within a jurisdiction, while other electronic payment solutions may be refused. The system may be developed with or without financial institutions involved (respectively, indirect and direct model) or as a hybrid solution with financial institutions involved only for a specific target market (European Data Protection Supervisor, 2023).

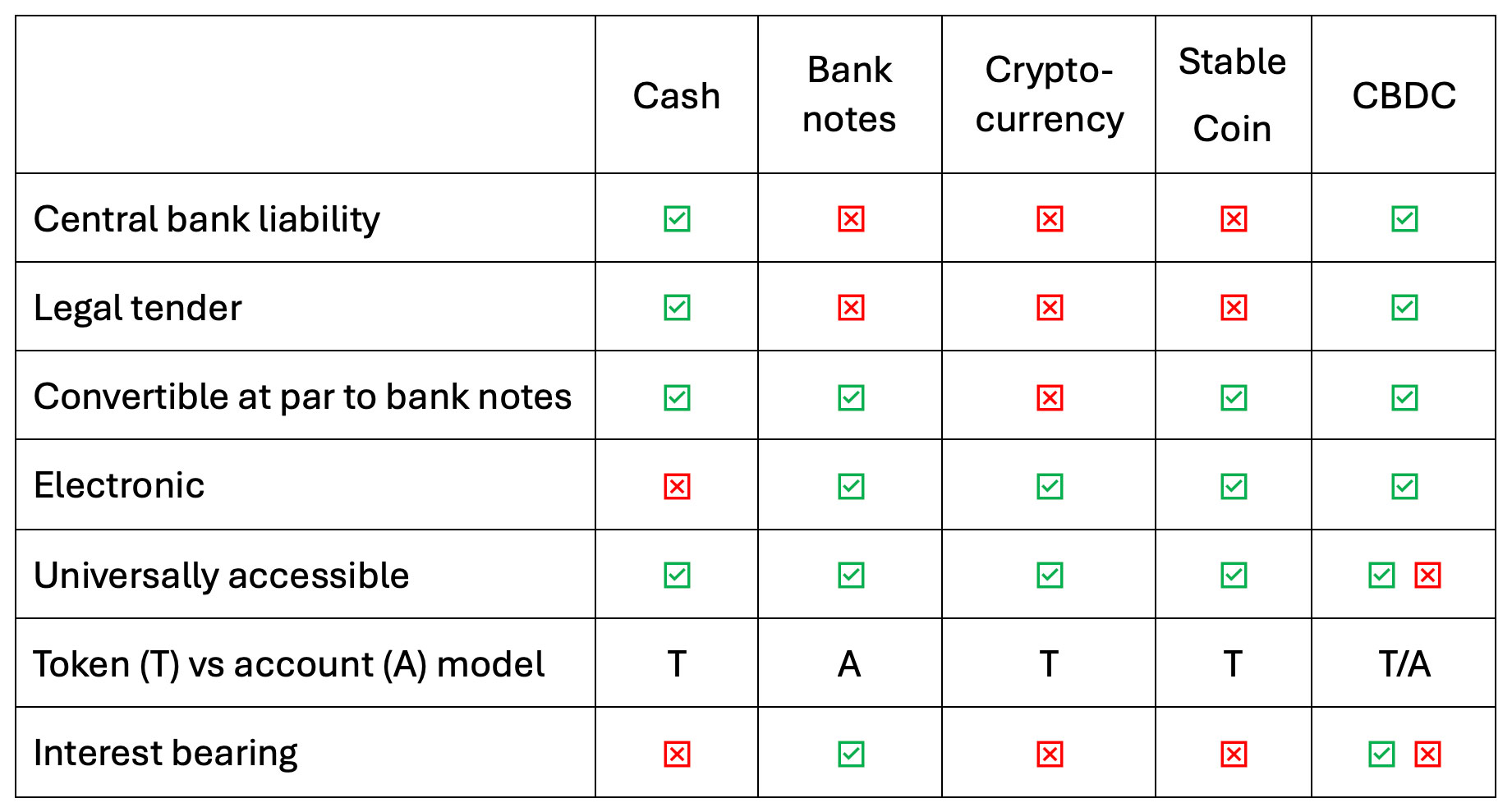

The main differences between the new cryptocurrency and other payment solutions can be explained in the following table, which compares rights related to different instruments already available in the main financial markets of developed and developing economies (see Table 2).

Table 2: CBDC and other payment solutions

Source: Author’s elaboration

CBDCs are the only alternative to cash that represents a central bank liability and has a legal tender. Unlike other cryptocurrencies, CBDC can be converted at par to banknotes like stablecoins and all the other more traditional payment solutions. The new payment solution is electronic, and it can be universally or locally recognized on the basis of the protocol adopted by the supervisory authority. Based on the Central Bank’s choices, the CBDC can be constructed with an account model that offers interest on deposits or as a token model that works like cash, cryptocurrencies, and stablecoins (UK Finance and EY, 2021).

This article describes the development of CBDC worldwide by considering the projects already implemented by different countries worldwide to underline the differences in the solutions adopted and the benefits and risks related to implementing the digitalization of the legal currency through the Digital Ledger Technology solution. A preliminary analysis describes the different projects currently being developed by leading countries worldwide by considering the various stages of development and the target customers (Section 2). A detailed analysis of the primary motivation for using CBDC is presented, starting from the BIS survey results by distinguishing the retail and wholesale sectors and the developed and developing economies (Section 3). The last section summarizes the main results and discusses the open issues for developing the central currency created on the Digital Ledger Technology and blockchain solutions.

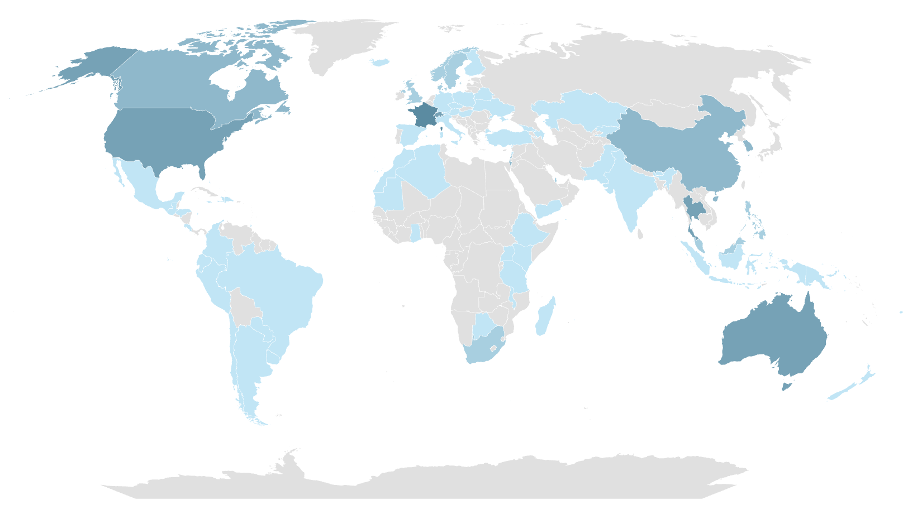

2. The state of the art of Central Bank Digital CurrenciesMany countries around the world started their CBCD projects in the last decades, mainly in Asia (42), America (23), Africa (21), and Europe (21) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Projects on Central Banks Digital Currencies by country

Source: CBDC tracker data processed by the author

Active CBDC projects are concentrated not only in the more developed or the more populated areas but also in Africa and Asia. There are a lot of countries that do not have a project that is already ongoing. On the opposite, there are countries more active in developing their own CBDC where more than one project is running in parallel, like Hong Kong (8), France (5), Singapore (5), Australia (4), Saudi Arabia (4), Switzerland (4), Thailand (4) and the United States (4). Surprisingly, the countries that have more projects on CBDC are not those in which cryptocurrency usage is higher (Table 1), so the motivation for developing the new money is not only driven by the demand for crypto-based assets or services.

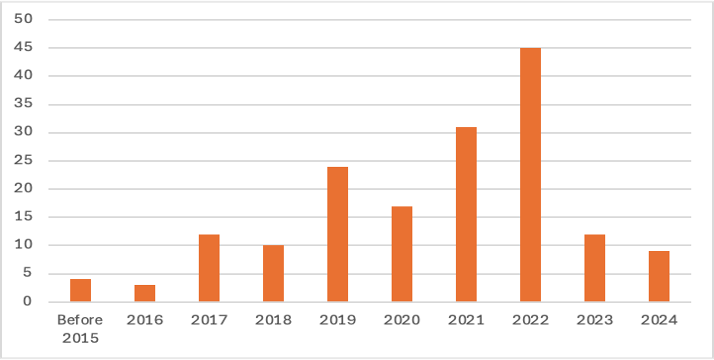

The first prototype of CBDC was launched in 1992 by the Central Bank of Finland and the aim was to develop a single national electronic system, and it is one of the few that was launched and operating for a few years. Only in three years (2019, 2021, and 2022) more than 100 new projects were launched (around 60% of the existing projects). (see Figure 2)

Figure 2: Launching date of Central Banks Digital Currencies projects

Source: CBDC tracker data processed by the author

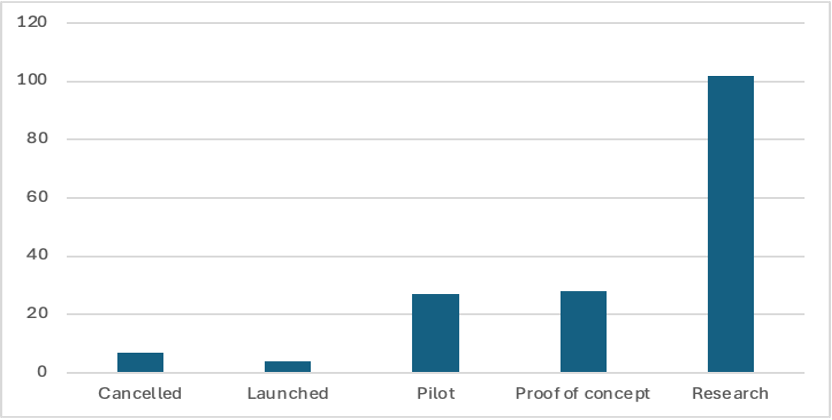

Most CBDC projects are still in the research stage (102), and only seven organized by the Philippines, Kenya, Denmark, Curacao, Singapore, Ecuador, and Finland have been canceled up to today. The more successful experiences were related to Jamaica, Bahamas, Zimbabwe, and Nigeria after 2020, which completed the development and pilot stage of the new digital currency. Hence, digital currency started to be used in the country in addition to the standard FIAT currency (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Stage of development of CBDC projects

Source: CBDC tracker data processed by the author

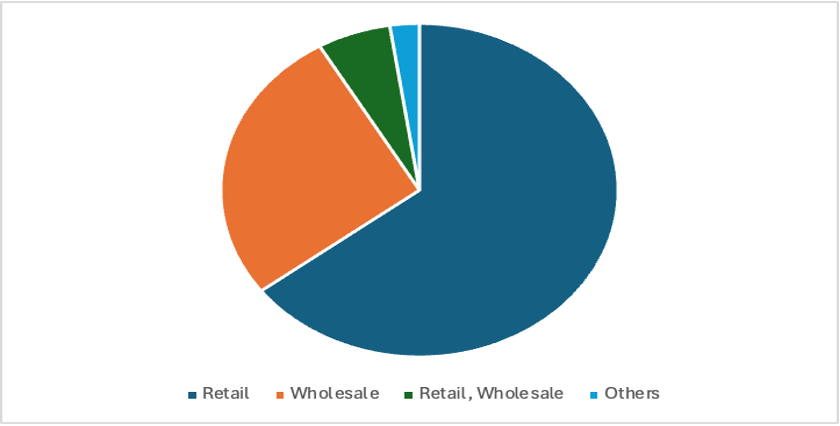

One key issue in defining the CBDC project is the target usage of the new currency that could be focused on retail payments and/or wholesale negotiations among financial institutions (BIS, 2023a). In the first case, the new currency will substitute partially the traditional currency while in the second case, the usage of the new payment solution is limited to trades among large investment banks and companies. There are several differences in the choices adopted for developing CBDCs (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Target sector for CBDC projects

Source: CBDC tracker data processed by the author

Most of the projects (64.7%) are addressed to retail payments management, and only 27% are for wholesale trade. As expected, the interest in retail solutions is mainly in developing economies, while wholesale trading matters only when very large transactions occur, and it happens primarily in developed economies (Deloitte, 2022).

In only 6% of cases, the project aims to develop a CBDC that could be used for retail and wholesale payments. Among these solutions, we have the exceptional and unique case of the Stella project, jointly organized by two Central banks (the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank) and the two other projects (Palau stablecoin and ZiG), which ensure the value of the digital currency through reserves (respectively USD$ and gold).

3. Main motivations for CBDC issuingCryptocurrencies raised interest from governments and monetary authorities due to the opportunities offered by the new technology for developing a new and different payment system. The main motivations for issuing CBDC are:

- Financial stability;

- Financial inclusion;

- Payment efficiency;

- Safety and robustness.

Cryptocurrencies offered by private institutions started to be accepted as payment solutions mainly in developing countries (like El Salvador), and there are already prepaid cards offered by large crypto exchanges that allow them to make purchases and pay bills through crypto-assets (BIS, 2023b). Monetary authorities are exposed to the risk of losing control of the money supply due to the increasing demand for alternative payment solutions not offered by regulated financial institutions. CBDC can compete with cryptocurrencies and represent the main instrument for reducing the development of payment solutions not controlled by a supervisory authority.

Worldwide, a lot of people are unbanked, do not have a bank account, or they are underbanked. They have a bank account and do not have access to financial services, and CBDC could be a solution for improving financial inclusion (Congressional Research Service, 2022). Cryptocurrencies may be readily offered to unbanked or underbanked citizens with lower costs for standard financial services.

Infrastructure costs related to CBDC are different with respect to traditional payment systems and the main issue for the research and development of the new infrastructure. Once the CBDC is in execution, the cost savings may be significantly more relevant than those of traditional payment systems (World Economic Forum, 2023). Differences may be primarily relevant for cross-border operations, particularly within the same area or to countries with which they share significant trade and financial linkages for which the efficiency of the payments system may be significantly improved thanks to the new technology adopted (IMF, 2023).

Cryptocurrencies are based on the Distributed Ledger Technology and allow to increase safety of the payment concerning cash payments and payment solutions offered by traditional financial institutions. CBDCs are regulated crypto-assets in which a supervisory authority may avoid currency volatility risk and protect its purchasing power over time (World Bank, 2021). The decentralized finance solutions that could be developed through the CBDC are also characterized by a higher resilience concerning traditional online payments because events that may affect one financial institution (like extreme climate events, operational and resolution risk) do not affect the overall system (IMF, 2022a).

The role of different motivations for developing CBDC is different for advanced and developing economies, and a BIS survey among Central Bankers and Governments highlights some interesting distinctions among them (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Survey on Motivation for CBDC issuing

Note: The figure presents the average value of the survey score by year with respondents’ scores that vary from 1 to 4.

Source: BIS data processed by the author

Financial stability is an issue that is relevant for both advanced and developing economies worldwide because individuals and companies are worried that a lack of market confidence may impact the currency’s value. In advanced economies, the main issue is related to volatility in the value of cryptocurrencies that, especially for individuals, may expose a risk of losses, and in extremely risky scenarios, a bank run may also happen in the crypto-lending market. In areas where a traditional financial institution serves less, cryptocurrencies are also used as an instrument for offering loans and, especially if the value of the crypto-asset is not linked to a real currency (stablecoins), the risk of bankruptcy of the alternative lending system may be higher than traditional lending supervised by national central banks (Gorton and Zhang, 2023). The development of CBDC may reduce the risk related to failures of private financial institutions and cryptocurrency marketplaces and increase the financial stability of the overall financial system even in economic crisis scenarios.

Monetary policy may be affected by the development of cryptocurrency markets because crypto payments may settle some of the trades. Empirical evidence shows that the role of transactions regulated by crypto-assets is growing, even if it is still minimal and concentrated in niche groups (BIS, 2021). In advanced economies, the main issue is to control the behavior of individuals who may already use other cryptocurrencies, so the CBDC is a solution to increase the control of the money supply and avoid alternative payment solutions. In less developed countries, the main advantage is developing a settlement system for large transactions among institutional investors. CBDC may represent a more effective solution concerning other more traditional solutions (like current rate pegging or foreign currency settlement). The interest in using the CBDC for monetary purposes is much higher in developing economies than in developed ones, even if the gap changes year-by-year (BIS, 2023c).

Financial inclusion is a relevant matter for developed and developing economies, but it matters the most in less developed countries where the percentage of the population without a traditional bank account is higher (Alliance for Financial Inclusion, 2022). CBDC represents an effective solution for areas where the technology infrastructure is limited and financial institutions are not interested in offering advanced financial services. Also, in the wholesale settlement, when there is no IT infrastructure already in place, the advantages of the CBDC could matter more concerning developed countries where alternative solutions are already available (BIS, 2020).

Cryptocurrencies may be used to regulate national payments by using cards or wallets that allow to make payments using crypto-assets. In this scenario, the cost of the service could be significant for the retail and the wholesale sector, and less expensive solutions based on CBDC are welcome from both enterprises and individuals. The demand for the service was stronger for developing economies in the past, but nowadays, there are no significant differences based on the degree of development of the country. The main driver of success is the availability of an infrastructure that allows one to monitor consumers’ transactions in real time and full online capabilities (Noll, 2023).

Cross-border settlements are usually exposed to currency risk and regulation risk, and especially for the wholesale sector, a CBDC solution may reduce the time necessary for completing the transaction and reduce the overall risk of the transaction. The main advantages are avoiding the limited operating hours and reducing the length of the transaction chains (BIS, 2022b). More developed economies are more active in cross-border payments, so the interest in developing a CBDC solution is higher in these countries than in developing ones.

The development of new technology decreased the demand for cash in both developing and developed economies. Some central banks started to promote the development of national digital retail payment systems that can compete with global platforms (Bofinger and Haas, 2023). Especially for the retail sector and the less developed economies, the interest in developing a CBDC is also driven by the demand for safe and secure payment solutions for citizens that are not offered by private financial institutions.

One of the key issues offered by CBDC is to construct a system that may also work offline and without power for people who live in remote places or where natural disasters frequently occur (IMF, 2022b). The development of offline solutions is mostly requested by developing countries or underdeveloped areas in developed countries.

4. Conclusion and further perspectivesDuring the last decades, several countries have been interested in studying and developing CBDC for the retail or wholesale market. Nowadays, only four countries have already implemented the new technology for payment services, while the majority of the projects are still in progress.

The main motivations for developing the CBDC are related to system stability, the inclusion issue, payment efficiency and safety. There are differences based on the target customers and the degree of development of the country that are relevant to the construction of the optimal strategy for implementing the new technology in the payment system.

CBDCs are not expected to replace fiat currency since the beginning, and Central Banks have to set a target for the supply of new digital currency and identify thresholds of ownership that could be applied to individuals or corporations. Currently, countries like the European Union are evaluating the holding restrictions that have to be used for citizens, companies, and foreigners for the implementation of the new digital currency (European Central Bank, 2024).

The issue of competition between CBDC and services offered by traditional financial institutions and an opportunity could be related to focusing mainly on the wholesale market to develop IT infrastructure in cooperation with commercial banks on a global scale. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates created a joint project with commercial banks for wholesale national and international payment and were able to develop and test a new blockchain-based model in only one year (BIS, 2022a).

CBDC may represent a disruptive innovation for the current financial system. Many financial institutions may be affected by the development of the new currency and lose their primary source of income (fees and services related to payment solutions). In order to avoid adverse effects on the stability of the financial system, regulation has to adopt a fine-tuning strategy for increasing the amount of new money available in the market smoothly and give time to the financial institution to adapt to the new competitive environment (Avgouleas and Blair, 2024).

One issue related to creating a CBDC is the risk of money laundering and financing terrorism and criminal activities related to user anonymity offered by DLT technology. Differently concerning other cryptocurrencies that a Central Bank does not manage, user anonymity could be an issue, and some countries (like the European Union) are evaluating new options in which payments do not disclose information about the payer and the receiver only if it is below a maximum threshold (European Central Bank, 2019). The threshold for the information disclosure rule may impact tax evasion issues, and a lower limit for user anonymity may improve tax collection and increase the fiscal base for the countries (United Nations, 2022).

References

Alliance for Financial Inclusion (2022), Central bank digital currency – an opportunity for financial inclusion in developing and emerging economies?. Special report. Available at www.afi-global.org (accessed December 24, 2024).

Avgouleas E., Blair W. (2024), “A critical evaluation of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs): Payments’ final frontier?,” Capital Markets Law Journal, 19 (2): 103-112. https://doi.org/10.1093/cmlj/kmae002

BIS (2020), “Proceeding with caution – a survey on central bank digital currency,” BIS paper 101. Available at www.bis.org (accessed December 24, 2024).

BIS (2021), “Impending arrival – a sequel to the survey on central bank digital currency,” BIS paper 107. Available at www.bis.org (accessed December 24, 2024).

BIS (2022a), “CBDC and its associated motivations and challenges – Saudi Central Bank,” BIS working paper 123. Available at www.bis.org (accessed December 24, 2024).

BIS (2022b), “Gaining momentum – Results of the 2021 BIS survey on central bank digital currencies,” BIS working paper 125. Available at www.bis.org (accessed December 24, 2024).

BIS (2023a), Lessons learnt on CBDCs. Report submitted to the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Banks Governors. Available at www.bis.org (accessed December 24, 2024).

BIS (2023b), “Financial stability risks from cryptoassets in emerging market economies,” BIS paper 138. Available at www.bis.org (accessed December 24, 2024).

BIS (2023c), “Making headway – Results of the 2022 BIS survey on central bank digital currencies and crypto,” BIS paper 136. Available at www.bis.org (accessed December 24, 2024).

Bofinger P. and Haas T. (2023), “The Digital Euro (CBDC) as a monetary anchor of the financial system,” SUERF policy Note n. 309. Available at https://www.suerf.org/ (accessed December 24, 2024).

Congressional Research Service (2022), “Central bank digital currencies: policy issues,” Available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/ (accessed December 24, 2024).

Deloitte (2022), “Central bank digital currencies: Building block of the future of value transfer,” Available at www2.deloitte.com (accessed December 24, 2024).

European Central Bank (2019), “Exploring anonymity in central bank digital currencies,” Available at www.ecb.europa.eu (accessed December 24, 2024).

European Central Bank (2024), “Macroeconomic modelling of CBDC: a critical review,” Available at www.ecb.europa.eu (accessed December 24, 2024).

European Data Protection Supervisor (2023), “Central bank digital currency,” Available at https://www.edps.europa.eu/ (accessed December 24, 2024).

Gorton G.B., and Zhang J.Y. (2023), “Bank Runs During Crypto Winter,” Harvard Business Law Review 14: 297-338. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4447703

IMF (2022a), “Behind the scenes of central bank digital currency emerging trends, insights, and policy lessons,” Available at www.imf.org (accessed December 24, 2024).

IMF (2022b), “Taking central bank digital currencies offline,” Available at www.imf.org (accessed December 24, 2024).

IMF (2023), “How should central banks explore central bank digital currency? A dynamic decision-making framework,” Available at www.imf.org (accessed December 24, 2024).

Noll F. (2023), “What consumer surveys say about the design of a U.S. CBDC for retail payments,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Available at https://www.kansascityfed.org/ (accessed December 24, 2024).

UK Finance and EY (2021), “Retail CBDC. A threat or opportunity for the payments industry?,” Available at https://www.ukfinance.org.uk/ (accessed December 24, 2024).

United Nations (2022), “Prospects and challenges of introducing a central bank digital currency,” Economic Analysis no. 163. Available at https://www.un.org/ (accessed December 24, 2024).

World Bank (2021), “Central Bank Digital Currency. Background technical note,” Available at https://documents1.worldbank.org (accessed December 24, 2024).

World Economic Forum (2023), “Central Bank Digital Currency Global Interoperability Principles,” Available at https://www.weforum.org/ (accessed December 24, 2024).