For many years, national wealth was marked by the control and possession of natural and physical resources. Human labor, agricultural output, minerals, and land were the foundations of any country’s economy. In the ancient systems of the 16th and 17th centuries, silver and gold were viewed as the direct indicators of a nation’s prosperity. Consequently, colonial expansion was validated by the acquisition of raw materials. In “The Wealth of Nations,” Adam Smith asserted that capital accumulation and productive labor replaced mercantilism as the leading driver of any country’s economic growth. The Industrial Revolution, which occurred between the late 18th and 19th centuries, shifted wealth creation to increased technological innovation and manufacturing capacity.[1] Britain’s economic supremacy was founded on mechanized production, steam power, and coal. It was closely followed by the emergence of Germany and the U.S. as global powers. During this period, wealth was defined using a resource-based lens.

However, it was increasingly mediated through the industrial output and productivity of nations. The oil boom of the 20th century exemplified this dependency, as countries with adequate fossil fuels, such as Russia and Saudi Arabia, gained significant economic and political advantages. Nevertheless, elements of transformation were evident during the oil-led period. The late 20th century was characterized by the emergence of finance, technology, and services, illustrating a slow wealth of detachment from tangible assets.[2] Innovation, education, and knowledge started to constitute an integral component of GDP, providing an opportunity for the rise of the digital economy that would influence the 21st century.

The Shift from Resource-Based to Data-Based Economies

The shift from resource-based to data-driven economies is a massive economic evolution of the contemporary era. Significantly, in the mid-20th century, knowledge, services, and information were integral components of the post-industrial economy. This transition materialized with the rise of the Internet, telecommunications, and computing from the 1980s to the late years. By the 2000s, data had become a vital production factor, whose significance could only be compared to that of capital, labor, and land.[3] Notably, the success of organizations, such as Alibaba, Facebook, Amazon, and Google, shows how value creation is correlated with the capacity to gather, monetize, and analyze information.[4] These companies have dominated the world’s economy through enormous data systems that underpin AI, logistics, and advertising.

The phrase, “data is the new oil,” which Clive Humby coined in 2006, explains this paradigm shift. Humby used this phrase to opine that data has similar attributes to oil since it can only generate value if it is extracted, improved, and distributed. However, data differs from oil since it is non-rivalrous. The international economy’s digitization implies that national wealth increasingly relies on innovation ecosystems, cyber capabilities, and data infrastructure instead of physical products. The transition further influences social and geopolitical dynamics. Countries, such as China and the U.S., which are global leaders in AI, cloud computing, and data production, have new types of power that surpass conventional industrial metrics. Nations endowed with natural resources but lacking efficient digital infrastructure may be at an increased risk of economic marginalization since competitiveness’ determinants transition from minerals and land to information systems and algorithms.

Measuring Wealth in the 21st Century

GDP is the most widely utilized indicator for measuring a country’s economic performance. However, many economists view GDP as an inadequate indicator for capturing the whole picture of a nation’s economic performance.[5] They claim that GDP cannot provide insights into whether a country is developing sustainably. Whereas GNI (“gross national income”) and GDP give an overview of a nation’s economic output, they fail to measure the multidimensional characteristics of modern prosperity, particularly in a world influenced by digital connectivity, knowledge, and data. The global economy has transitioned from tangible goods’ production to information monetization, management, and creation. Subsequently, new mechanisms for measuring wealth should consider intangible assets, including data resources, digital infrastructure, innovation capacity, and intellectual property.

One primary transition is the recognition that data and intellectual property are the leading factors that influence modern wealth. In the current knowledge-based economies, value generation depends on information flows, education, digital infrastructure, and innovation. For instance, Amazon, Apple, Google, and other technology firms accumulate most of their wealth from brand equity, data analytics, and algorithms (intangible assets) instead of physical assets. The shift from resource-focused to knowledge-oriented economies requires upgraded accounting systems that consider these intangible products. Moreover, social well-being and sustainability are modern determinants of wealth measurement. Countries should measure stocks of their social, human, and natural capital. The comprehensive portfolio, which encompasses social, human, natural, financial, and produced capital, can guide countries in measuring their wealth.[6] Models, such as the IWI (“Inclusive Wealth Index”), GPI (“Genuine Progress Indicator”), and HDI (“Human Development Index”), seek to integrate social equity, environmental quality, and human capital into national prosperity assessments. These multidimensional strategies emphasize that long-term wealth creation depends on promoting equitable opportunities, strengthening education, and sustaining natural ecosystems.

Digital transformation has promoted initiatives that focus on quantifying data wealth. Notably, data wealth refers to the value of digital infrastructure, cybersecurity, and assets. Countries leading in digital governance, cloud computing, and AI tend to view data as a vital resource that can be compared to 20th-century oil. Indicators, such as the “OECD’s Digital Economy Outlook” and DESI (European Union’s “Digital Economy and Society Index”), attempt to measure data use, innovation capacity, and digital readiness. They stipulate that a country’s wealth currently depends on its capacity to govern, analyze, store, and gather data. Competition based on technological development and innovation has intensified the geopolitical tensions between China and the United States.[7] Moreover, localization and sovereignty are new economic terms that depict the growing recognition that data is a strategic resource and asset. Therefore, nations have started to treat data as a component of their national wealth, implementing legal models that control its cross-border flow and ownership.

Data as a New Economic Asset

Data’s economic power arises from its scalability and versatility. It supports the Fourth Industrial Revolution’s foundational technologies, including automation, predictive analytics, machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI). Governments and organizations use data to provide personalized products, forecast trends, and optimize operations. Processing makes data more valuable through ML feedback loops and network effects. Unlike tangible products, data can be reutilized without depletion (United Nations 2019). It has a nearly zero marginal reproduction cost, transforming it into an unmatched engine of countries’ economic growth. Nonetheless, data’s economic value relies on its alignment with digital ecosystems, accessibility, and quality. Unprocessed and raw data have minimal utility. Consequently, its refinement through analytics, software processing, and algorithms turns it into economic capital.

From a macroeconomic viewpoint, data facilitates efficiency gains across diverse economic sectors. For instance, in the agricultural industry, sensors and satellites can strengthen yield forecasting. Big data improves healthcare delivery, disease surveillance, and decision-making in the healthcare sector.[8] Therefore, data’s new economic role is evident through its correlation with productivity. However, data-driven economies are also exposed to multiple challenges. Critical issues, such as algorithmic bias, digital monopolies, cyber threats, and data privacy, are today’s leading economic concerns. Data concentration within a few MNOs (“multinational organizations”) raises concerns related to countries’ sovereignty and market competition. It has led to surveillance capitalism, which occurs when data extraction becomes a mechanism for accumulating wealth. Thus, these asymmetries can be managed through global collaboration and regulatory innovation.

Impacts on Economic Growth and Development

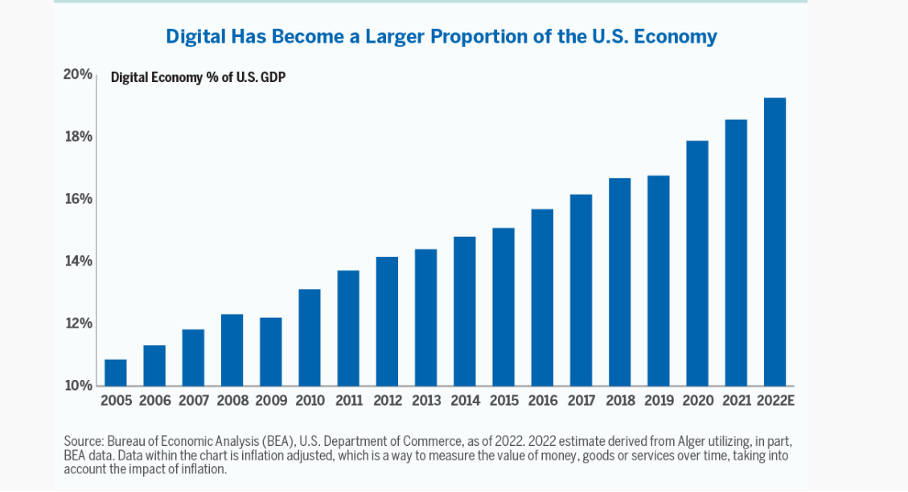

Data factors are the digital resources and information that are fundamental to business and social activities. These resources and details provide economic benefits to users and owners. In contemporary economies, data is recognized as a modern production factor alongside land, capital, and labor. As a production factor, data has a considerable effect on national core competitiveness. Its strategic significance as an economic factor is recognized worldwide, prompting major economies to integrate its growth into their national initiatives. The U.S. created the “Federal Data Strategy Action Plan” in 2020 to use data as a leading strategic resource.[9] Similarly, the European Union developed the “Data Strategy and AI White Paper” to explore how data can be incorporated into key sectors, such as healthcare and industry. The bar graph below shows that the digital economy is a major driver of the U.S. GDP growth due to innovations within e-commerce, cloud computing, and software sectors. It highlights that the digital economy’s contributions to the U.S. GDP have been rising since 2005.

Figure 1: The impact of the digital economy on the U.S. GDP

Retrieved from https://www.alger.com/Pages/OnTheMoney.aspx?pageLabel=AOM321

Data serves as a multiplier and catalyst for countries’ economic growth. It improves efficiency by promoting targeted innovation, predictive modeling, and real-time decision-making. Manufacturing, logistics, healthcare, finance, and other industries that use data effectively tend to attain massive productivity gains. In supply chain management, utilizing big data analytics can reduce waste and operational expenses. Similarly, utilizing big data in the healthcare sector reduces treatment costs and enhances patient outcomes. These improvements’ cumulative impacts translate into increased economic resilience and output. Further, empirical evidence highlights that nations with open-data ecosystems and strong digital infrastructure experience increased job creation, competitiveness, and accelerated GDP growth.[10] Conversely, it suggests that countries that lag in digitization risk missing growth opportunities and widening development gaps.

The emergence of the digital economy has widened the explanation of value creation. Intangible assets, including digital platforms, algorithms, patents, and software, constitute a large percentage of global capital. The large share symbolizes a transition to innovative economic frameworks. Countries, such as Singapore, South Korea, and the U.S., demonstrate this pattern since their economic competitiveness relies on data analytics abilities, research, and innovation. This shift has also triggered the emergence of new industries, notably cloud computing, cybersecurity, and AI. These industries have promoted technological advancement and diversification. Despite these economic benefits, data creates new forms of dependency and inequality.[11] The digital gap between developed and developing countries reflects past industrialization disparities. Wealthy countries own major digital platforms, cloud networks, and data centers, dominating the digital economy infrastructure. Conversely, developing nations provide raw data to advanced economies without reaping the same benefits. Subsequently, they risk depending on other countries’ technology providers, generating a digital type of neocolonialism.

Digitization’s environmental footprint poses immense challenges. For instance, data centers consume enormous amounts of water and energy, resulting in carbon emissions.[12] The rise of data processing and storage requires sustainable technologies to address environmental costs. Governments have a critical role in ensuring that data leads to equitable development. They can invest in effective governance, infrastructure, and digital literacy to perform this role. Moreover, governments should formulate policies that foster digital entrepreneurship, cybersecurity, and data access to promote inclusive economic growth. Further, they should collaborate with international institutions, private firms, and public organizations to democratize data advantages.

[1] Mengchen Jiang, “A Review of the Impacts of the Industrial Revolution in World History,” Communications in Humanities Research 39, no. 1 (2024): 234-239. https://doi.org/10.54254/2753-7064/39/20242245.

[2] World Bank Group, “Fintech and the Digital Transformation of Financial Services: Implications for Market Structure and Public Policy: Fintech and the Future of Finance Flagship Technical Note,” 2022, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099735304212236910/pdf/P17300608cded602c0a6190f4b8caaa97a1.pdf.

[3] Ping Huang and Xiaohui Chen, “The impact of data factor-driven industry on the green total factor productivity: evidence from China,” Scientific Reports 14, no. 25377 (2024): 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77189-w.

[4] Kean Birch, DT Cochrane, and Callum Ward, “Data or asset? The measurement, governance, and valuation of digital personal data by Big Tech,” Big Data & Society (2021): 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211017308.

[5] Yale School of the Environment, “Going Beyond GDP to Measure the Changing Wealth of Nations,” 2025, https://environment.yale.edu/news/article/going-beyond-gdp-measure-changing-wealth-nations.

[6] Livia Bizikova, Rob Smith, and Zakaria Zoundi, Measuring the Wealth of Nations: A review, 2021, International Institute for Sustainable Development, https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/measuring-wealth-nations-review.pdf.

[7] Melody Musoni, Poorva Karkare, Chloe Teevan, and Ennatu Domingo, Global approaches to digital sovereignty: Competing definitions and contrasting policies, ECDPM, The Center for Africa-Europe relations, 2023.

[8] Fiona Walsh, Anna Zhenchuk, Corey Luthringer, Christoph Kratz, and Florian Schweigert, “How big data analytics can strengthen large-scale food fortification and biofortification decision-making: A scoping review,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1552, no. 1 (2025): 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.70028.

[9] Zhaopeng Chu, Xin Chen, and Jun Yang, “Impact of data factor and data integration on economic development: Empirical insights from China,” Telecommunications Policy 49, no. 8 (2025): 103004, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2025.103004.

[10] Roman Chinoracky, Natalia Stalmasekova, Radovan Madlenak, and Lucia Madlenakova, “Are Nations Ready for Digital Transformation? A Macroeconomic Perspective Through the Lens of Education Quality,” Economies 13, no. 6 (2025): 152, https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13060152.

[11] Thi Lam Ho, Le Hong Ngoc, Thu Hoai Ho, “Digital exclusion or inclusion: Exploring the moderating role of governance in digitalization’s impact on income inequality in developing countries,” Research in Globalization 10 (2025): 100283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2025.100283.

[12] Marie-Hélène Hubert and Thomas Le Texier, Environmental Impact of Digitalization, Asian Development Bank, 2025.