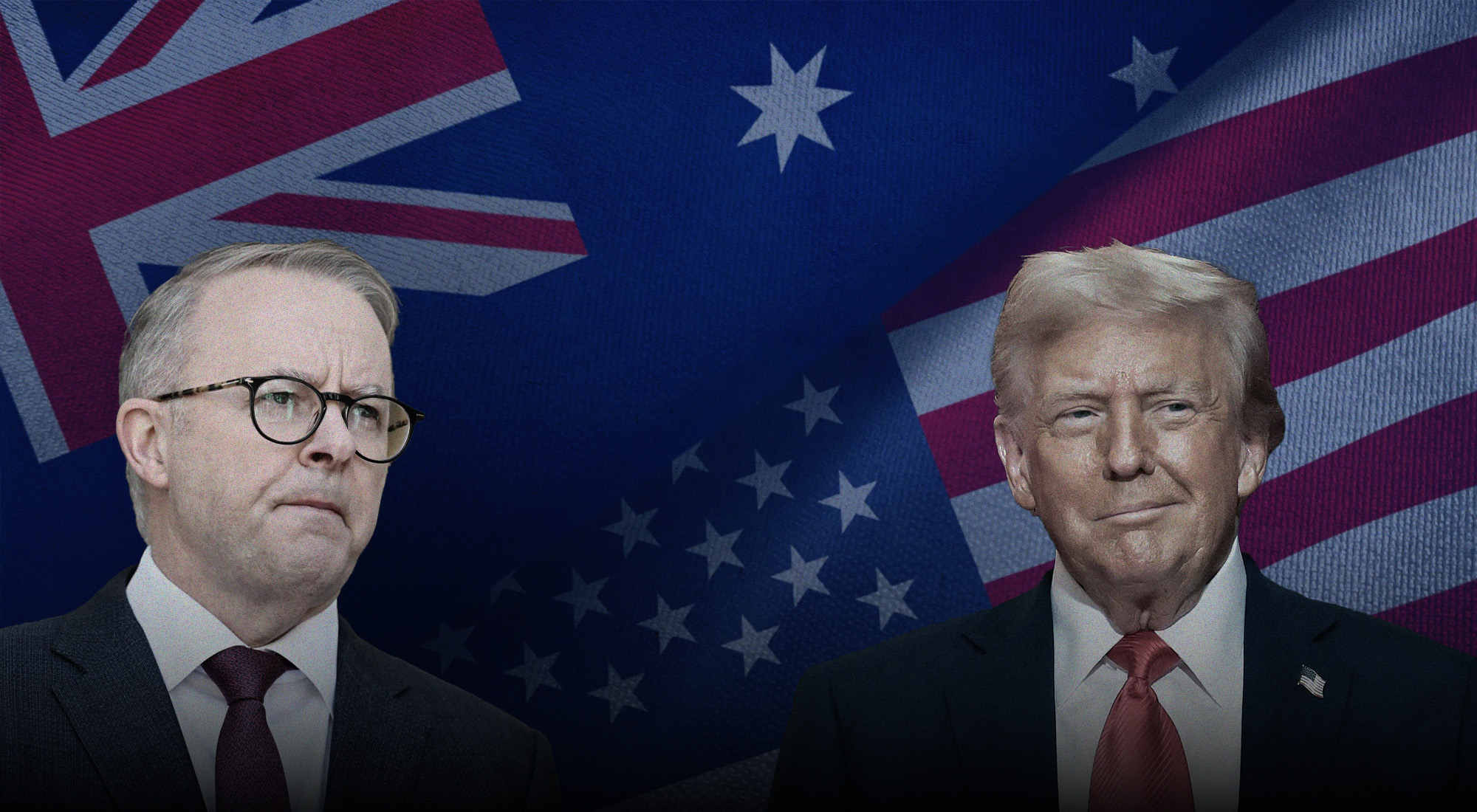

Ever since the advent of the Trump administration, the Anthony Albanese leadership in Australia has underscored headwinds in the United States (U.S.)-Australia defense and economic partnership. Australia has resisted U.S. pressure to ramp up its defense spending target to 3.5 percent, akin to the type of pressure applied by the United States on allies within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), signaling a search for strategic autonomy within Canberra as tensions in the Indo-Pacific intensify.[1] At the same time, Canberra’s purchase of supersonic missiles from Washington, expansion of its offensive strike capabilities, and Australia’s quest for a leaders’ meeting—with an eye on China—suggest an element of convergence with Washington, despite the defense spending reservations.[2]

On the economic front, Australia’s medium-term economic strategy for Southeast Asia points to a deepening recognition of Australia-Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) regional integration. This could mark a point of friction with the Trump administration, given ASEAN and Australia’s largely united position against U.S. tariffs, and Washington’s limited desire to bring the levies to a “zero” baseline, signaling greater space for Canberra to hedge against U.S. trade policies.[3]

With Canberra slated to walk a tightrope on defense and economic ties with the United States, what strategies can it employ to break future ground with Washington? And do the benefits of convergence outweigh the costs?

Defense and Economic Realities

Australia’s involvement in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD), a 2007 security grouping that involves India, China and the United States, could become a point of strain with Washington. There is very limited enthusiasm in Canberra for a militarized QUAD, given the need to prioritize Australia’s economic partnership with ASEAN. Look no further than the country’s 2040 Southeast Asia Economic Strategy: it puts a premium on forging trade and economic links that benefit from Southeast Asia’s four-percent growth rate, well beyond the next decade.[4] Part of these stakes could require Australia to be more receptive to ASEAN’s non-interventionist diplomatic approach to the South China Sea, where the Trump administration has been planning to court Asian allies and challenge perceived Chinese “aggression.”[5]

Canberra’s overt support for U.S.-led pacts, including the nuclear submarine “AUKUS” deal, could also validate fears in ASEAN that Australia is approaching a zero-sum military approach against China, the bloc’s top trading partner. This zero-sum redline is grounded in ASEAN’s “Outlook on the Indo-Pacific”, a strategy that is officially endorsed by Australia.[6] Thus, the Trump administration’s concerted push to isolate China and ramp up targeted alliances, such as the U.S.-Philippines defense alliance, could complicate Australian Premier Anthony Albanese’s push to present Canberra as a long-term peacebuilder in the region.

Australia’s strategies to maneuver between a defense-focused Trump administration, an increasingly neutral ASEAN, and its top trading partner—China—may require some bold decisions this year. This includes the need to set certain guardrails that help protect its multi-billion-dollar economic relationship with ASEAN.[7] But from where things stand, ground realities suggest Australia has very limited bargaining power with the Trump administration. A proof point is the ongoing Pentagon review of AUKUS, the three-party pact on U.S. nuclear submarine supplies to Australia, as domestic concerns over Washington’s supply volume loom large.[8]

Counterproductive trade agreements with the Trump administration and rising uncertainty over the future of tariff concessions also provide valuable lessons that Washington is willing to revisit some of the long-standing constants in this all-important Australia-U.S. strategic relationship.[9] Given that the AUKUS review is being conducted in the Pentagon, and its future could emerge largely on the Trump administration’s own terms, Canberra lacks an ironclad guarantee to give to ASEAN states who have balked at the nuclear submarine pact and could see its continuity as a measure of Australia’s less credible “neutrality” posture.

The stakes to court ASEAN at the expense of the Trump administration are considerable this year. Australia is in the process of shifting from a supply chain procurement to a supply chain advancement sphere in Southeast Asia and is branding its investment, export, and human capital potential as existing capacities that favor ASEAN’s middle class—valued at about 190 million people.[10] Australia’s past shortcomings in economic diversification, headlined by the 2019 COVID-19 pandemic, have also made clear that the country cannot overly depend on a few markets to achieve long-term economic self-sufficiency. ASEAN, with its astounding growth potential, multi-vector foreign policy, and multiple tiers of commercial investment hubs, fits the bill as a dependable Australian market.

Washington’s desire to do away with a “charity”-focused model of U.S. overseas assistance and willingness to favor those nations with “the ability and willingness to help themselves”, creates space for more contingency planning on Australia’s part.[11] This policy shift demonstrates the limits of overly relying on the Trump model of “America First” to inform Australia’s own choices on ASEAN, where work on green energy, critical minerals, and the digital economy requires sustained goodwill and consistency. These two elements of policy planning appear largely absent from the current Trump approach to negotiations with the Anthony Albanese leadership.

Australia’s Challenge of Dual Messaging: Deterrence and Diplomacy

While Canberra’s approach to regional security in the Asia-Pacific is focused on offsetting some Chinese influence, the absence of a coherent U.S. strategy underlines the gulf between collective deterrence and unilateral diplomacy. For instance, Australia has been bolstering security arrangements with Pacific Island Countries (PICs) such as Papua New Guinea (PNG) and the Solomon Islands, amid concerns that China was looking to position itself as a key security partner.[12] But from Australia’s viewpoint, deterring Chinese security influence—including policing arrangements and suspected patrols of the South Pacific—is a challenge in itself, given the lack of enduring consensus on China’s perceived and actual role with PICs. Consider climate change—Beijing’s increased traction with PICs, evidenced at the 2025 China-Pacific Island Countries Foreign Ministers’ Meeting, is informed by the view that advanced economies need to fill the climate mitigation leadership gap to inform breakthroughs on top regional priorities.[13] These include rising sea levels, fossil fuel spillovers, and the threat of climate-induced migration. PIC’s endorsement of such priorities as a key security imperative makes it critical for Australia and the United States to close ranks behind these interests in a bid to secure buy-in for their regional stability role.

Prospects for such an outcome appear bleak in 2025. First, there is very limited appetite for climate-friendly policy advocacy in Washington, and the Trump administration’s decision to greenlight U.S. deep-sea mining in the Pacific risks a trust deficit with the PICs.[14] Australia, which is on course to bolster its climate commitments domestically and can position itself as a renewable energy superpower, is largely at odds with Washington’s climate skepticism, making an enduring partnership on shared PIC-Australia climate commitments untenable. For Canberra, navigating climate commitment constraints with Washington would prove to be a tough challenge, given Australia’s push to significantly step up financial assistance to key Pacific Island countries in its vicinity, and its recognition that international cooperation on climate change is critical to address its adverse impacts.[15] Until recently, Washington has been a key part of that climate advancement effort, with millions committed for modernizing early warning systems, smart agriculture, disaster preparedness, and coastal adaptation. The Trump administration’s climate retreat and a drastic roll-back of past USAID assistance suggest Australia may have to resort to unilateral climate diplomacy in the region.

Strategies for Advancing Shared Interests

Australia has several opportunities to advance shared interests with the Trump administration. On defense, there is growing concern in Washington that the AUKUS agreement could prove counterproductive to America’s own submarine industrial base, and Australia’s prior memory of committing billions to advance the U.S. industrial base should allay some of those concerns.[16] The very trilateral nature of the agreement—involving Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom—based on shared threat perceptions of future aggression in the region, shows that providing competitive, Virginia-class nuclear-powered submarines to Australia is ultimately in Washington’s own interests.

These considerations should form the backbone of Australia’s high-level defense talks with Washington this year, where there is still insufficient emphasis on value addition for the U.S. submarine industrial base. It is a fact that Canberra made US$500 million in AUKUS payment ahead of a key U.S. defense secretary meeting in February, but the scale and depth of nuclear submarine production warrant a grip on industrial sentiment in the U.S., prospects for long-term cost-sharing with Australia, and ways to expand the ambit of the original AUKUS framework.[17] The nuclear submarine pact is already estimated to cost Canberra US$368 billion over the course of thirty years, and the Pentagon review suggests that changing industrial considerations could have a bearing on the AUKUS pact’s long-term continuity.[18] To synthesize these competing expectations, there is a stake in both Canberra and Washington to further evolve the contours of the original AUKUS agreement to make it more in sync with ground realities.

The Anthony Albanese leadership can also invite long-term support from the Trump administration by framing the AUKUS deal’s emerging technology component in the interests of Washington’s indigenization push. There is evidence to suggest that the United States is ramping up efforts to bolster the innovation of emerging technologies at home. It is reflected in the Trump administration’s “Big, Beautiful Bill”, which has raised anticipation for tax credits that U.S.-focused semiconductor firms could use to expand advanced manufacturing in the country.[19] By framing the AUKUS deal’s advanced technologies component as an endorsement of the “America First” doctrine—a key consideration in the Pentagon’s ongoing review—Australia can emerge better positioned to allay fears that U.S. support would undermine its own supply chain localization. After all, Australia is on course to ramp up its domestic production capacity of components that are critical to defense and cutting-edge technology systems, supporting the view that U.S. manufacturers would not have to disproportionately shoulder the burden of defense technology production on their own. Direct communication of these efforts can serve as a win-win proposition for both sides, allaying Australia’s fears of astronomical costs of missile production while advancing U.S. confidence that domestic manufacturers would benefit from Australia’s indigenous production support.[20]

On economics, Albanese may have to set up some guardrails in managing the Australia-China economic partnership. This is critical to ensure that the relationship does not undermine Canberra’s own strategic ties with Washington. Developments over the years have shown that the United States can easily leverage its concerns over China’s alleged “economic coercion”, trade engagement, and other threat perceptions over the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to demand that Australia endorse U.S. concerns.[21] That approach could demand a fundamental rethink under Albanese, who has succeeded in establishing a cooperative strategy to deal with Beijing: cooperate on interests that serve both leaderships, while compartmentalizing differences.

Areas of Australia-China cooperation include climate security, multi-sector export and manufacturing support, long-term market access, and a multiyear effort to ensure that political tensions, evidenced during the COVID-19 pandemic, do not alter hard-won goodwill in Australia’s mega trade partnership with Beijing. China remains Australia’s largest trading partner, accounting for over US$213 billion in exports and a total trade volume of over US$321 billion in 2024.[22] As Australia’s mining and energy export earnings risk a slump from the Trump administration’s trade barriers, the resulting pressure from domestic businesses in the next two years could prompt Albanese to further pivot toward China to offset these external economic pressures.[23] That could demand greater heft and craftsmanship in navigating existing tariff and defense spending tensions with Washington, where the appetite to favor Chinese market access over U.S. strategic interests is minimal.

The domestic sentiment on Albanese’s U.S. and China foreign policies could also shape the trajectory of acceptable diplomatic balancing options. For instance, there is greater domestic confidence in Australia’s ability to lead influence in the Pacific, with 39 percent of Australian citizens now viewing their country as the dominant player in a region previously held by China.[24] Those perceptions come at a time when U.S. influence in the Pacific also wanes, a factor true for some 81 percent of Australians who express sharp disagreement with the Trump administration’s tariff policies.[25] Those policies, with considerable potential to upend Australian manufacturing and strain critical supply chains that are central to Australian consumers, could prompt the Albanese administration to pivot more closely toward China.

The stakes for such a pivot are clear. Australian manufacturers, including wine and barley, were key players in pressing Canberra to take a more reconciliatory foreign policy position toward China in the past years, when Australian support for a U.S.-backed “COVID-19” inquiry drew China’s ire and pushed relations to new lows. Beijing’s success in sustaining Australia’s business growth, inviting unrivaled market access in key export sectors, and the potential to broaden it further through their Free Trade Agreement (FTA), are viable incentives. Limited prospects of respite from President Trump, evident in his decision to open up tariff talks with select allies and forego tangible negotiations with others, could prompt Australian policymakers to prioritize consistency over unpredictability. China’s success in serving as Australia’s top trading partner since 2009 provides a track record of trade and economic consistency that is unlikely to be matched by an increasingly volatile trade and investment climate under Trump.[26] Together, these contrasting offerings could raise the stakes for Albanese to promote more high-level dialogue engagements with Beijing and further detether the Australia-China trade relationship from any U.S.-led trade war pressure.

There are early signs that a more autonomous Australian trade policy could take shape. Look no further than the remarks of Australian Trade Minister Don Farrell, who issued a rare critical clarification to Washington that Canberra will not side with the United States to bring Australia’s own trade relationship with China under pressure.[27] Given the fact that China is a considerably high-scale purchaser of Australian exports in comparison to the United States, Canberra’s position on maintaining its strategic autonomy with China could strengthen further this year. Beijing’s policy of opening up and the potential for increased imports of Australian commodities serve as important merits. Anthony Albanese’s highly anticipated visit to China this year, despite limited breakthroughs in securing a similar arrangement with Washington, also makes it certain that Australia is exercising alternative options to ease trade and economic challenges—a central consideration for domestic stability at home.[28]

Conclusion

Ultimately, Australia is looking at a complex web of defense understandings with Washington, which will entail deft workarounds and a more assertive foreign policy. Washington’s mixed signals on AUKUS may prompt a rethink of Australia’s costs and benefits of engaging in a pact that the United States, based on its own industrial considerations, may not necessarily commit to in the long term. However, Australia and the United States’ defense partnership is still likely to weather differences on defense spending, given the centrality of QUAD to Australia’s alliance projection in the Pacific.

But as competition in the Pacific increases, the Anthony Albanese leadership could make it its mission to strike a delicate balance between strategic alignment with Washington on defense and regional threats while protecting its economic interdependencies with Beijing. The fact that Australia cannot confidently rely on the Trump administration suggests Canberra’s tightrope diplomacy is set for a tough test this year.

[1] Bruce Xin Tao, “Australia Rejects US Push for Increased Defense Spending,” The Diplomat, June 6, 2025, https://thediplomat.com/2025/06/australia-rejects-us-push-for-increased-defense-spending/.

[2] “Australia says US missile purchase shows commitment to defence spending,” Reuters, July 3, 2025, www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/australia-says-us-missile-purchase-shows-commitment-defence-spending-2025-07-03/.

[3] “US tariffs on Australia ‘should be zero’, Albanese says as leaders prepare for end of Trump’s 90-day pause,” The Guardian, June 30, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2025/jun/30/anthony-albanese-us-trump-tariffs-australia.

[4] Nicholas Moore AO, “Invested: Australia’s Southeast Asia Economic Strategy to 2040,” Australian Government, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, September 1, 2023, https://www.dfat.gov.au/southeastasiaeconomicstrategy.

[5] Simone McCarthy, “US defense chief Hegseth vows to counter ‘China’s aggression’ on first Asia visit,” CNN, March 28, 2025, https://edition.cnn.com/2025/03/27/asia/pete-hegseth-asia-tour-philippines-marcos-intl-hnk

[6] See “ASEAN and Australia,” Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australia, https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/southeast-asia/asean-and-australia

[7] Nicholas Moore AO, “Invested: Australia’s Southeast Asia Economic Strategy to 2040.”

[8] Sam Roggeveen, “Clock ticks towards Pentagon AUKUS review deadline,” The Lowy Institute, July 7, 2025, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/clock-ticks-towards-pentagon-aukus-review-deadline.

[9] “Australia navigates uncertainty of U.S. agreements in the Trump era,” The Washington Post, July 4, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/07/04/australia-us-military-rubio-aukus/

[10] CY Park and B Yeung, “An Integrated and Smart ASEAN: Overcoming Adversities and Achieving Sustainable and Inclusive Growth,” Asian Development Banking Institute Working Paper No. 1267, May 2021, p. 4.

[11] “Trump to host five African leaders next week to discuss ‘commercial opportunities’,” Reuters, July 3, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/first-trump-africa-summit-be-held-next-week-semafor-reports-2025-07-02/.

[12] “Pacific Islands delay security plan that could open door to China,” Reuters, June 26, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/pacific-islands-delay-security-plan-that-could-open-door-china-2025-06-26/.

[13] Kathryn Paik and John Augé, “China Courts the Pacific: Key Takeaways from the 2025 China–Pacific Island Countries Foreign Ministers’ Meeting,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 3, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/china-courts-pacific-key-takeaways-2025-china-pacific-island-countries-foreign-ministers.

[14] Dan Ackerman, “Trump administration considers a new way of extracting minerals in the Pacific Ocean,” NPR, June 26, 2025, https://www.npr.org/2025/06/26/nx-s1-5432636/trump-administration-considers-a-new-way-of-extracting-minerals-in-the-pacific-ocean.

[15] “Australia commits US$200 million to support climate action in Asia and the Pacific,” Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, November 18, 2024, https://www.dcceew.gov.au/about/news/aus-commits-support-climate-action-asia-pacific.

[16] Daniel Hurst and Julian Borger, “Aukus: nuclear submarines deal will cost Australia up to $368bn,” The Guardian, March 13, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/mar/14/aukus-nuclear-submarines-australia-commits-substantial-funds-into-expanding-us-shipbuilding-capacity.

[17] “Australia makes $500 mln AUKUS payment ahead of US defence secretary meeting,” Reuters, February 7, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/australia-makes-500-mln-aukus-payment-ahead-us-defence-secretary-meeting-2025-02-07/.

[18] Jonathan Barrett and Patrick Commins, “Aukus will cost Australia $368bn. What if there was a better, cheaper defence strategy?,” The Guardian, June 14, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/15/aukus-will-cost-australia-368bn-what-if-there-was-a-better-cheaper-defence-strategy.

[19] Alicia Diaz and Mackenzie Hawkins, “Chipmakers Win Bigger Tax Credit Under Bill Passed by Senate,” Bloomberg, July 2, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-07-01/chipmakers-win-bigger-tax-credit-under-bill-passed-by-senate.

[20] “Australia navigates uncertainty of U.S. agreements in the Trump era,” The Washington Post, July 4, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/07/04/australia-us-military-rubio-aukus/.

[21] “Mike Pompeo blasts China’s ‘coercion’ of Australia as cyber-attack likened to Parliament House hack,” Australian Associated Press, June 20, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/20/mike-pompeo-blasts-chinas-coercion-of-australia-as-cyber-attack-likened-to-parliament-house-hack.

[22] Cameron England, “Exports to China Slumped 9 Per Cent Despite Warmer Ties,” The Australian, January 29, 2025, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/politics/australias-exports-to-china-show-signs-of-passing-peak-after-exports-fell-9-per-cent-in-2024/news-story/d6a4177b394fb08106a59ff473445990.

[23] Nick Toscano, “Australian exports to tumble as Trump’s tariff war hits home,” The Sydney Morning Herald, June 30, 2025, https://www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/australian-exports-to-tumble-30b-as-trump-s-tariff-war-hits-home-20250627-p5mavn.html?js-chunk-not-found-refresh=true.

[24] “Australia overtakes China in the Pacific as America vacates the lane,” The Lowy Institute, June 17, 2025, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/australia-overtakes-china-pacific-america-vacates-lane.

[25] “Australia-United States: How to disagree with a superpower,” The Lowy Institute, July 2, 2025, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/australia-united-states-how-disagree-superpower.

[26] Kandy Wong, “Australia eyes lands of opportunity amid trade diversification despite warming China ties,” South China Morning Post, October 5, 2024, https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3281092/australia-eyes-lands-opportunity-amid-trade-diversification-despite-warming-china-ties.

[27] “Australia won’t join Trump trade war on China,” Australian Financial Review, May 15, 2025, https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/australia-won-t-join-trump-trade-war-on-china-20250515-p5lzhg.

[28] “Australia’s Albanese to address Darwin Port sale on China visit,” South China Morning Post, July 7, 2025, https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3317184/australias-albanese-address-darwin-port-sale-china-visit.