The 11 dashes drawn on the map during the Chinese Civil War (1945-1949), which were later changed to 9 and then 10 dashes, may have contributed to the creation of the world’s “most dangerous conflict no one is talking about.”[1] That line claimed China’s sovereignty over more than 90% of the South China Sea (SCS).[2]

This insight aims to expand on China’s stance on the South China Sea dispute, an angle many researchers bypass when investigating the dynamics of the dispute. In other words, the study seeks to clarify China’s policy toward the South China Sea. Accordingly, this paper is organized into 3 sections. The first section will analyze China’s position on the dispute, the second will investigate China’s behavior and actions to support its position, and the third will further examine China’s justifications of its policy toward the dispute vis-a-vis the other riparian countries, including the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia. But before elaborating on these sections, the paper sheds some light on the historical background of the South China Sea conflict.

Historical Background

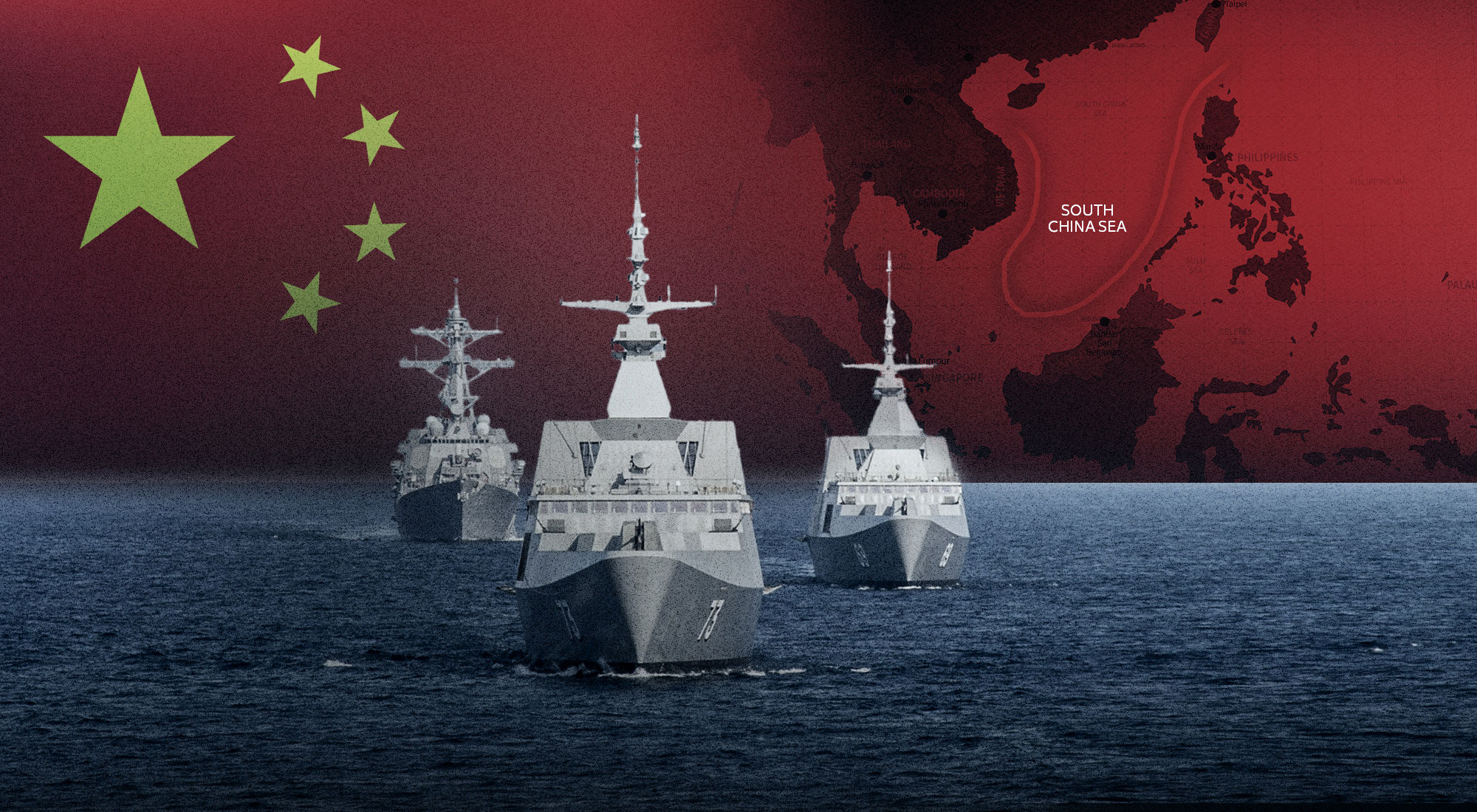

The dispute in the South China Sea stemmed from the Chinese Civil War, specifically during 1947, when the Nationalist party introduced its “11-dash” line, claiming sovereignty over the majority of the area. Upon the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Communist Party of China, led by Mao Zedong, considered itself the rightful successor to the South China Sea by changing the “11-dash” line to a “9-dash line”. The claims by the new government in Beijing have led to military confrontations between China and the other countries that had controlled several islands and reefs in the South China Sea. China started the process of reclaiming the Paracel Islands from South Vietnam in 1974 after oil and gas reserves were discovered in the area.[3] This has been the starting point of regional disputes with other riparian countries in the region. As Map 1 shows, China’s 9-dash line claims overlap with the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of four different countries (Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei).

Map 1: South China Sea Dispute

Source: Rachael Bale, “The South China Sea Dispute Is Decimating Fish Stocks,” National Geographic, August 29, 2016, https://shorturl.at/0CDOb

China’s Position

China’s position in the South China Sea can be categorized into five main pillars, as follows:

- China has historical rights and sovereignty over the waters and islands in the South China Sea.

- The 9/10-dash line represents the focal catalyst for China’s policy toward the South China Sea.

- China completely rejects any external intervention in the South China Sea.

- China encourages developing a Code of Conduct of Parties (COC) in the South China Sea, negotiated between China and ASEAN.

- China’s policies are based on the rules of international law.

Being the first country to discover and name the islands in the South China Sea, and while governing the islands, China has established its sovereignty over the territories for a millennium.[4] In efforts to solidify its sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China released a statement in 2016. China coined a new term, “Nanhai Zhudao”, to refer to the islands in the South China Sea and to affirm its sovereign rights on the islands. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has introduced Nanhai Zhudao as Chinese sovereign territories one day after the International Court of Arbitration’s (ICA) rejection of the 9-dash line. Nanhai Zhudao consists of four main islands: Dongsha Qundao (Dongsha Islands/Pratas Islands), Xisha Qundao (Xisha Islands/Paracel Islands), Zhongsha Qundao (Zhongsha Islands/Macclesfield Bank), and Nansha Qundao (Nansha Islands/Spratly Islands).[5] China further claims that there have been 2000 years of Chinese activities in the named islands and internal waters, in addition to holding the exclusive economic zones to the lands and waters based on Nanhai Zhudao.[6] The Chinese government has put forward concepts with the aim of strengthening its claim of sovereignty and historical rights over the islands and waters of the South China Sea.

Seeking to solidify its historical claim to the South China Sea, upon the founding of the People’s Republic of China on 1 October 1949, the 9-dash line represents China’s sovereignty and historical rights only over the islands and waters. However, the 9-dash line is drawn in dashes rather than a single line to represent that this is merely the area where China has exclusive sovereignty over its islands and waters without blocking the navigation of neighboring countries in the area.[7] A 9-dash line transformed in 2023; following joint naval drills of the Philippines and the United States, a new map containing a 10th dash included a larger part of the sea and encompassed the island of Taiwan and the majority of the Spratly Islands as Chinese territory.[8] Regardless of the most relevant countries’ rejection of the 9/10-dash line presented by China, it undoubtedly remains the focal catalyst in its policies.

Correspondingly, China’s policy is to reject any foreign interference in the South China Sea since it would undermine the regional peace. In an attempt to demonstrate its hegemony, the United States has been sending spy planes over the South China Sea on a regular basis. Beijing responded by making it clear that it will not submit to Washington’s intimidation and that it will proceed with its reclamation and construction work on the islands that are part of its territory.[9] Furthermore, China believes that in order to achieve peace and cooperation in the South China Sea, relevant countries should strengthen communication and coordinate to solve maritime disputes without the inclusion of any external forces.[10]

By emphasizing coordination between China and the countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), China promotes developing a Code of Conduct (COC) regarding the South China Sea. In March 2025, the Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, Chen Xiaodong, delivered a speech at the Asia Annual Conference and highlighted some key points toward China’s stance on the South China Sea. He stressed that the discovery of oil and gas resources in the 1970s in the area has led other countries to illegally invade Chinese territories and claim them as their own. He added that China will always prioritize peace and stability in its approach toward the South China Sea dispute while emphasizing that Beijing has shown great restraint in addressing the issues. Moving ahead, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s vision will be followed as he believes that China should be the anchor for stability and growth of the South China Sea, while protecting its territories simultaneously.[11] This aspect has shown that China is fully willing to work with ASEAN to develop the Code of Conduct, which both parties agreed to finalize in the fall of 2026.[12]

Developing the Code of Conduct would benefit the countries in the region by encouraging them to cooperate with China and guiding all states to settle their disputes. However, China and the countries of ASEAN disagree on two main provisions when it comes to developing a COC. First and foremost, China’s refusal of external powers’ influence in the region has led to proposing the development of a notification mechanism that would inform all relevant countries of any military activities between ASEAN countries and countries outside the region; these military activities would only resume when the parties are notified and hold no objection. Subsequently, another suggestion by China is that the cooperation in the exploration of natural resources is strictly with the countries in the region.[13] ASEAN members reject the provisions that were presented by China, hindering the process of developing a COC. This slow process of developing the COC does not alter the initiatives that China is taking in order to finalize it.

Furthermore, China has always declared that its policies are in accordance with international law. The Cairo Declaration and the Potsdam Proclamation have always been the cornerstones for China as they are fortifying its standpoint. According to the Cairo Declaration in 1943, after the surrender of Japan in World War II, it was pledged that Manchuria, Taiwan, and the Pescadores Islands would be returned to China.[14] On the other hand, the Potsdam Proclamation (1945) stated that Japanese sovereignty would be limited to 4 islands, and any other islands that were occupied would be reclaimed in accordance with the Cairo Declaration.[15]

The two documents are of great importance when it comes to China setting its policies toward the South China Sea dispute, as they are serving as a legal basis for China’s demands of historical claims regarding sovereignty over the Sea. China considers that its policy has always been to defend the international order by safeguarding its territorial sovereignty and its maritime interests. According to Xiaodong, China continued to practice sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea in accordance with Chinese national law, international law, and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).[16] That pillar of China’s position may raise a question of why China refused to accept the ruling of the ICA in 2016. To elaborate, China has deemed that the Philippines’ unilateral initiation of the arbitration is a violation of both the UNCLOS and their mutual agreement with China on solving the dispute by negotiation, as well as that this arbitration opposes the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea signed by China and all ASEAN countries, including the Philippines, in 2002.[17] China has maintained its stance on upholding international law and UNCLOS and would refuse any endeavor that would undermine them.

China’s Behavior

By examining China’s behavior toward the ASEAN countries, we are delving into the real dynamics of the most dangerous dispute in the world, as it may lead to a confrontation between China and the U.S. China has taken various initiatives to deal with the claimant countries in the South China Sea. Vietnam and the Philippines face more assertiveness from China, while countries like Brunei and Malaysia have different approaches. By 1974, after the discovery of oil and gas reserves in the islands, China started asserting dominance by first seizing the Paracel Islands from South Vietnam, and later gaining control over parts of the Spratly Islands in the following years.[18] This has ignited the clashes between claimants in the South China Sea, as China is looking to assert its sovereignty over the islands according to the 9-dash line introduced in 1947.

To illustrate, China’s presence in the South China Sea has become more evident by starting the land reclamation process of the islands since the start of the 21st century, in addition to building naval bases on the reclaimed land.[19]

States have followed different approaches to tackle the issue of Chinese assertiveness. The Philippines’ approach is the so-called “transparency initiative”, where Manila is aiming to strengthen its alliances with other countries, increase military presence in the South China Sea, as well as strategically utilize international law. The Philippines has doubled down on its transparency initiative since President Ferdinand Marcos assumed office in 2022. He expanded the relationship with the U.S., which will build four new military bases in the Philippines.[20] The aim of the Philippine government with this strategy is to challenge what it describes as China’s “grey-zone” tactics. However, having U.S. military bases in the Philippines may lead to confrontations between two of the world’s greatest powers. In response to the transparency approach that the Philippines is taking, Beijing has positioned more military vessels in the Philippines’ waters. This has led to several clashes between China and the Philippines; most recently, in September 2025, a Philippine fishing vessel was confronted by the Chinese Coast Guard, in addition to collisions taking place near Scarborough Shoal.[21] This specific clash led to the Principal Deputy Spokesperson for the U.S. Department of State, Tommy Pigott, condemning China and describing the actions as a disruption in regional stability.[22]

The clashes have a high risk of escalation if any casualties happen, as the Philippines may resort to the Mutual Defence Treaty with the U.S. Dragging external forces into the SCS may increase the chance of confrontation. Moreover, China has been conducting underwater survey operations very close to Vietnam’s EEZ, specifically Vietnam’s oil and gas reserves. However, Hanoi took another route to tackle the situation. Similar to China’s reclamation process, Vietnam started its own procedure by building its own artificial lands and military bases in the South China Sea. This has helped Vietnam solidify its claim, along with strengthening its security cooperation with other countries in the region.[23] This shows China’s resolve when it comes to holding onto the territories in the South China Sea.

Furthermore, Malaysia is a claimant country that is no different from the previously mentioned. China’s largest coast guard ship moved into Malaysia’s EEZ in 2023.[24] Apart from this, Brunei, also being a claimant country, faced alleged incursions into its EEZ. Rather than following an aggressive policy, Brunei chooses to have a “Silent Claim” in its EEZ disputes and would not follow the Chinese vessels in its EEZ.[25] Although it has the status of a non-claimant, Indonesia has claimed to be neutral on the South China Sea dispute, although it has repelled Chinese vessels from its EEZ.[26] China’s usage of military vessels is its primary way to fortify its claims according to the “9-dash” line. It considers this as safeguarding its territories in the South China Sea.

On the same note, China still takes the initiative to settle matters peacefully. It has made agreements and cooperated with claimant countries in the South China Sea. China describes its policy as “Choosing olive branch over sword”, and in this regard, it has moved forward with the peaceful actions it is taking.[27] For example, it had an agreement with Vietnam and the Philippines in 2005 to have a Joint Marine Seismic Undertaking on an agreed area.[28] With the same objective, China has reached a consensus with Indonesia on cooperative development in their overlapping territories in 2024, as well as other cooperation initiatives to prove that it will always prioritize peace and stability over forcefully protecting its territories.

China’s Justifications

Historical rights and binding international law are the two main anchors to China’s justification at any point in the South China Sea dispute. First, China will always justify its actions by highlighting its historical rights to the islands by presenting maps or recalling proof from other countries’ statements or declarations. As an example, China has used a memorandum released by the United Kingdom government in 1974 stating that it was apparent that the islands were under Chinese care by the start of the 20th century.[29] This and many other statements released by other governments act as a backbone to emphasize its historical rights to the islands. Second, China has constantly referred to international law declarations as a basis for its actions, namely the Cairo Declaration and the Potsdam Proclamation, as discussed earlier.

Furthermore, the Chinese government has always maintained its sovereignty over the islands in the SCS despite attempts to intervene in their sovereign territories. The efforts to meddle in the SCS islands that were started by other states in the 1970s deteriorated from the terms of the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties (DOC).[30] The Declaration of Conduct of Parties (2002) demonstrates a set of rules signed by ASEAN and China on the South China Sea dispute in efforts to improve cooperation between riparian countries.[31] Nevertheless, the claimant countries refuse to acknowledge China’s incursion into their EEZ set by the UNCLOS based on “national” maps, in addition to the strict refusal of the “9/10-dash line” set by the Chinese government dating back to 1947.

Conclusion and Future Insight

In examining China’s viewpoint on the SCS dispute, a stance that many countries around the world differ with, further gives a clearer analysis of the dispute and its dynamics. The Chinese government is a firm believer that the islands and waters are its sovereign territories, despite the EEZs that were introduced by UNCLOS. This does not change the fact that all countries in the region, including China, have increased their presence in the SCS after the discovery of oil and gas reserves. The dispute has stretched since the introduction of the “9/10-dash line”, which has made external factors intervene in the region. Being one of the most important trade zones globally, all claimant countries would want to benefit from their EEZ and would not accept China’s claim to the islands in the SCS.

The daily disputes over this strategically significant sea have turned it into the “world’s most dangerous conflict no one is talking about” because no one is paying enough attention to it. China’s stance on the sea is just as important as that of other riparian countries in the dispute. Many would disregard the position of the Chinese government and its justification and focus closely on the ASEAN countries and the external forces acting in the sea. In summary, this strategically important trade route needs to be examined from all sides, as it is pivotal for the global economy.

[1] Timothy McLaughlin, “The Most Dangerous Conflict No One Is Talking About,” The Atlantic, December 2, 2023, https://shorturl.at/xa8HZ.

[2] Miles Kenny, “Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea,” Encyclopædia Britannica, April 11, 2024, https://shorturl.at/31oF8.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ding Duo, “China Safeguarding Sovereignty and Peace in South China Sea,” CGTN, September 4, 2025, https://shorturl.at/28wS7.

[5] Nguyen Luong Hai Khoi, “China’s Recent Invention of ‘Nanhai Zhudao’ in the South China Sea (Part 1: The Birth of ‘Nanhai Zhudao’),” US-Vietnam Research Center, University of Oregon, February 18, 2020, https://shorturl.at/2imuX.

[6] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, Statement of the Government of the People’s Republic of China on China’s Territorial Sovereignty and Maritime Rights and Interests in the South China Sea, July 12, 2016, https://shorturl.at/lZtQ8.

[7] Hannah Beech, “South China Sea: Where Did China Get Its Nine-Dash Line?” TIME, July 19, 2016, https://shorturl.at/PNLRM.

[8] Kenny, “Territorial Disputes”.

[9] Wang Hui, “US Should Keep Away from South China Sea,” China Daily, May 27, 2015, https://shorturl.at/OsGaA.

[10] “Xinhua Commentary: Joint Efforts Needed for Stability, Prosperity in South China Sea,” Xinhua, August 22, 2025, https://shorturl.at/SqAim.

[11] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “China: An Anchor for Peace and Development in the South China Sea,” March 27, 2025, https://shorturl.at/1u9L3.

[12] Beech, “South China Sea”

[13] Rajaram Panda, “Why a Code of Conduct on South China Sea Remains Elusive?” Vivekananda International Foundation, March 26, 2024, https://shorturl.at/OGN6O.

[14] Encyclopaedia Britannica, s.v. “China — U.S. Aid to China,” updated October 20, 2025, https://shorturl.at/0xflq.

[15] United States, Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, The Conference of Berlin (the Potsdam Conference), 1945, Volume II, Document No. 1382 (Proclamation by the Heads of Government, United States, China and the United Kingdom, July 26, 1945), accessed October 21, 2025, https://shorturl.at/kVw13.

[16] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “China: An Anchor for Peace”

[17] CGTN. “Explainer: Why China Rejects the South China Sea Arbitration Award.” CGTN, July 12, 2025, https://shorturl.at/QNAv7.

[18] Kenny, “Territorial Disputes”.

[19] Kenny, “Territorial Disputes”.

[20] Daniela Braun and Florian C. Feyerabend, “Flash Point in the South China Sea,” International Reports, April 14, 2025, https://shorturl.at/Cr5ba.

[21] Nathan Strout, “China, Philippines Continue to Clash over Fishing Rights in South China Sea.” SeafoodSource, October 3, 2025. https://shorturl.at/sI99o.

[22] Sebastian Strangio, “US Backs Philippine Ally After Latest Maritime Clash With China,” The Diplomat, October 14, 2025. https://shorturl.at/b0DlO.

[23] Braun and Feyerabend, “Flash Point”.

[24] RFA Staff. “Report: China Coast Guard ‘More Robust Than Ever’—Ships Conduct Almost Daily Patrols in the South China Sea, a Study Found,” Radio Free Asia, January 31, 2023. https://shorturl.at/AC9wF.

[25] Bama Andika Putra, “Brunei’s Silent Claims in the South China Sea: A Case for the Theory of Trade Expectations,” Cogent Social Sciences 10, no. 1 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2024.2317533

[26] “Indonesia’s New Leader Calls for Collaboration With China Before Heading to the US,” NBC News, November 10 2024, https://shorturl.at/gSGEh.

[27] Duo, “China Safeguarding Sovereignty”.

[28] “Security and Stability in the South China Sea,” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of the Philippines, March 15, 2005, https://shorturl.at/8DXYL.

[29] “GT Investigates: Records from US, UK Provide Solid Proof of China’s Sovereignty over South China Sea Islands,” Global Times, September 22, 2025, https://shorturl.at/oHzQj.

[30] “China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea: Defending history, upholding international order,” China Institute of South China Sea Studies, July 13, 2025. https://shorturl.at/jvPlV.

[31] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “China: An Anchor for Peace”