The climate crisis in 2025 continues to worsen, posing significant and widespread threats to both public health and the environment. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO), in its “State of the Global Climate 2024” report, emphasizes that anthropogenic climate change has reached unprecedented levels, with 2024 being the warmest year within the 175-year observational record. Global temperatures have surpassed the pre-industrial period by more than 1.5°C, averaging 1.55 ± 0.13°C, surpassing the previous warmest year, 2023, at 1.45°C ± 0.12°C above the 1850-1900 baseline.[1] Within Africa, ongoing warming trends correspond with the worldwide rise in average temperatures, with the continent experiencing the warmest decade on record in 2024. The WMO report highlights that these temperature anomalies have amplified existing challenges, such as water scarcity, food insecurity, and energy systems, which require new opportunities and tools to meet these challenges.[2]

The Energy-Water-Food (EWF) nexus is considered the conceptual framework that sheds light on the interconnectivity and interdependence between water, energy, and food systems. These core systems form the pillars of human well-being, economic development, and environmental sustainability.[3] They do not function in isolation; instead, they impact and depend on one another in multifaceted ways. For example, water is a requisite for both energy production and agricultural irrigation. Conversely, energy is required for water extraction, purification, distribution and for powering farming equipment and food processing. Similarly, food production patterns shape both energy and water demand. Demographic pressure further intensifies these challenges.

While the threat of climate change constitutes a global crisis transcending national borders, this insight centers on East Africa, where climate change intensifies systemic vulnerabilities across the nexus. East Africa refers to a region comprising states such as Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Burundi, among others, that have faced severe interlinked challenges related to resource scarcity. The region is categorized by rapid population growth, climate variability, and urban expansion, all of which strain the water, energy, and food systems. Utilizing the EWF nexus framework, this article seeks to bridge the divide between theoretical understanding and practical policy implementation, offering insights into both the core opportunities and the risks associated with persistent disjointed development.

Water Security Under a Changing Climate

In East Africa, water stress and scarcity persist as significant challenges influencing the EWF nexus. Throughout Africa, it is estimated that approximately 250 million people are affected by high water stress, with projections indicating that this situation may displace up to 700 million people by the year 2030.[4] Extreme weather phenomena pose escalating threats to the region, as heavy rainfall leads to flooding and prolonged droughts result in water shortages. According to the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), through its Climate Prediction and Applications Centre (ICPAC), it was stated at a press conference in the Kenyan capital of Nairobi in 2022 that the East African region experienced higher temperatures and below-normal rainfall that year.[5] According to IGAD, between 15.5 and 16 million people in East Africa require urgent food aid due to the ongoing drought. Specifically, it is reported that approximately 6 to 6.5 million people in Ethiopia, 3.5 million in Kenya, and 6 million in Somalia are experiencing severe water and pasture shortages. These shortages are resulting in reduced food production, substantial losses of livestock and wildlife, and an increase in resource-related conflicts.[6]

Among the East African nations, Kenya is classified as one of the water-scarce countries globally, with an annual per capita water availability of less than 1000 m³. It is important to note that a country is considered water-stressed if its per capita water availability falls below 1,700 cubic meters (m³) annually.[7] The water scarcity situation has deteriorated in most developing countries due to rapid population growth, economic development, and urbanization, making it challenging to address the issue and provide adequate sanitation services. Tanzania, by comparison, is considered water-abundant; however, its diverse climate and geological conditions lead to substantial seasonal, interannual, and spatial fluctuations in water availability, as well as challenges related to water quality. Water stress in Tanzania is deemed moderate, according to the Falkenmark Water Stress Index, as the total annual renewable water per capita amounts to 1,680 cubic meters.[8] Across the region, weak infrastructure remains a critical factor, limiting the ability to store, distribute, and manage available resources effectively.

According to the World Bank, irrigation accounts for 70% of global freshwater withdrawals, despite covering only 20% of agricultural land.[9] Nonetheless, it is responsible for 40% of global food and fodder production and 55% of the total value of agricultural output. Irrigation pumping also accounts for 6% of global electricity consumption and significantly contributes to methane emissions, especially from irrigated rice.[10] These figures underscore the severity of sustainable resource management and the considerable pressure exerted on water and energy systems by agricultural demands.

Energy Systems Under Climate Stress

Transitioning over to energy, the International Energy Agency (IEA) reports that in Sub-Saharan Africa, 35 million people gained access to electricity in 2023. However, population growth during the same period added nearly 30 million people, resulting in a net gain of only about 5 million people with access. Despite such progress, the region now accounts for 85% of the global population without electricity, up from 50% in 2010.[11] According to 2023 data, 18 of the 20 countries with the largest electricity access deficits are located in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nigeria (86.6 million), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (79.6 million), and Ethiopia (56.4 million) together represent more than one-third of the world’s population without access to electricity.[12] In rural areas, electricity access rates are 35% in Ethiopia, 19% in Tanzania, 13% in Uganda, and 69% in Kenya, indicating a significant gap between urban and rural areas regarding electricity access.[13]

However, this has not halted efforts toward renewable energy projects in East Africa. For example, the hydropower potential of Ethiopia is estimated to reach upwards of 4500 MW, considered the highest in Africa.[14] In terms of geothermal energy, Kenya holds the title of leader in the region, as it produces over 863 MW of geothermal energy.[15] However, the full potential of hydropower and geothermal energy is not utilized to the fullest by the two countries, respectively. While hydropower is becoming a reliable source of electricity in Ethiopia, climate variability poses a significant risk to its sustainability. The region has faced severe droughts in past decades, which reduced water flow in the reservoir and brought a heavy impact on power generation. Due to low reservoir levels, Kenya was compelled to cut hydroelectric generation and depended largely on costly diesel generators and imports. It highlights water-energy interdependence in the region.

Agriculture, Food Security, and Climate Challenges

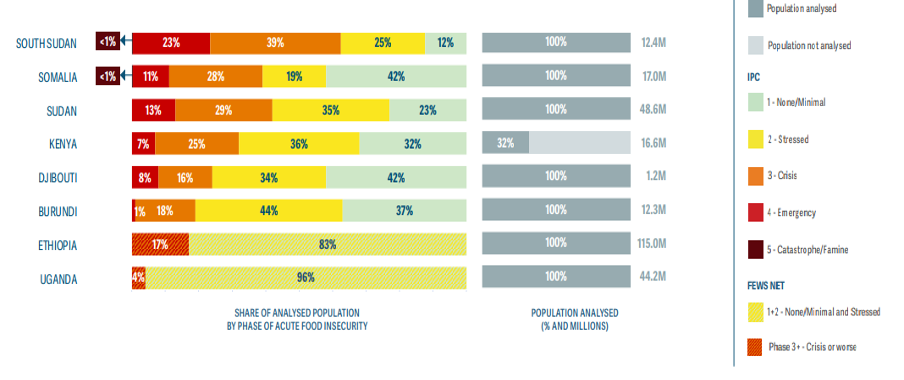

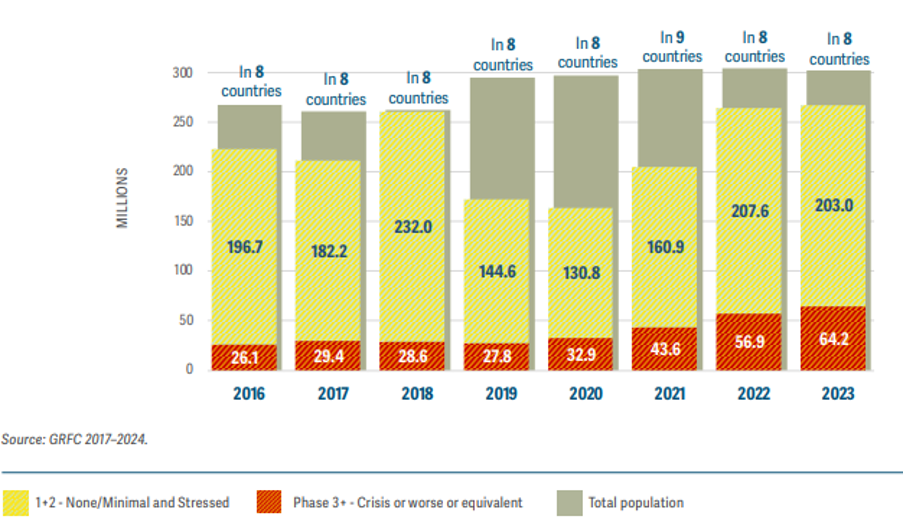

Within East Africa, food systems remain highly vulnerable to climate variability, land degradation, socio-economic pressures, and inadequate infrastructure. According to the United Nations, 685 million individuals, with over 80% residing in Sub-Saharan Africa, continue to lack access to electricity.[16] Simultaneously, over 400 million Africans lack access to basic drinking water, and more than 250 million suffer from food insecurity.[17] These statistics underscore the imperative to formulate nexus-informed strategies that concurrently address multiple resource systems. Food insecurity remains a persistent challenge across the region, with millions of people facing recurring shortages of nutritious food and disruptions to agricultural production. According to the “Global Report on Food Crises for East Africa 2024” by ICPAC, 64.2 million people, or 24% of the analyzed population, faced high levels of acute food insecurity in 2023 across eight East African countries.[18] Similarly, according to the 2025 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report, between 638 and 720 million people experienced hunger in 2024, reflecting a reduction of 15 million people compared to 2023 and a decrease of 22 million compared to 2022.[19] However, this trend contrasts with the reality in Africa, where hunger has steadily risen across the region; the proportion of the population facing hunger in Africa surpassed 20% in 2024, affecting 307 million people. It is projected that 512 million people could be chronically undernourished by 2030.[20] Nearly 60% of these individuals will reside in Africa.

Figure 1: Analyzed population according to the phase of acute food insecurity in East Africa in 2023

Figure 2: Number of people suffering from acute food insecurity in East Africa up to 2023

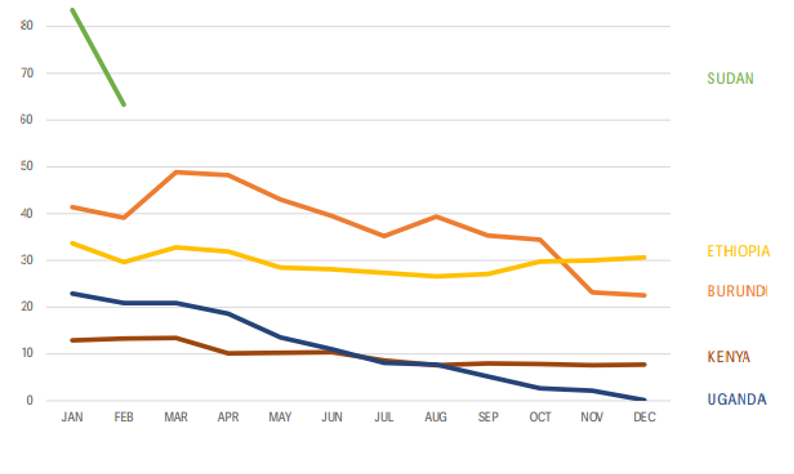

Figure 3: The highest food inflation in East Africa in 2023

Source: https://www.icpac.net/documents/867/GRFC2024-regional-east-af.pdf.

The persistence of this food consumption gap is linked to extreme weather patterns affecting countries such as Kenya, Uganda, Somalia, Ethiopia, Burundi, and others. Below-average rainfall from 2020 to 2023 led to the most severe drought in the Horn of Africa in nearly four decades, significantly impacting livestock production and crop yields. Additionally, this period saw sudden increases in food prices, thereby straining household purchasing power. Soil becomes incapable of absorbing heavy rainfall, leading to livestock losses. In Ethiopia, over 40% of agricultural land suffers from nutrient depletion and soil erosion, which reduces productivity and creates significant shocks and vulnerabilities within the food system.[21] Underdeveloped infrastructure impedes food access in East Africa, thereby impacting food import and export activities. The African continent heavily depends on cereal imports, a reliance significantly influenced by infrastructural deficiencies. For instance, Kenya relies on importing 80% of its wheat requirements, all of which are affected by inadequate road infrastructure in the region.[22] This necessitates inclusive, climate-resilient, and integrated policies to develop sustainable agriculture. Despite ongoing national initiatives, policymaking in East Africa often remains trapped in isolated sectoral silos. For example, water ministries typically operate independently of energy or agriculture departments, leading to fragmented investments and inefficiencies. In this context, integrated planning emerges not only as a technical requirement but also as a critical socio-political imperative for addressing the nexus of water, energy, and food.

Urbanization and Population Pressure

On the Energy-Water-Food nexus, rapid population growth and urbanization are posing significant pressure. According to the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, as of 2024, population growth in East Africa remains the highest, with Kenya’s population surpassing 55 million, Ethiopia’s exceeding 130 million, and Uganda’s population exceeding 48 million.[23] At the same time, many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, including some in East Africa, report among the lowest life expectancy rates globally, though they are predicted to see significant improvements over the course of the century.[24] Excessive urbanization is exerting substantial pressure on infrastructure, residential accommodation, and public services. The demand for essential resources such as clean water, electricity, food, and sanitation is projected to rise significantly, thereby impeding their supply. Overloading of electrical grids may lead to frequent power outages. Vulnerabilities in the supply chain, along with demand-supply fluctuations, place considerable strain on the urban food system. The pressure brought about by urbanization threatens the loss of peri-urban agricultural land and exacerbates concerns related to food and water security. According to the UN, by 2050, Africa’s population is expected to reach 2.5 billion.[25] Generally, population growth has been identified as the primary factor hindering the achievement of sustainable goals in energy, water, and food systems that can support an entire nation without compromise. Adding to the ever-growing population of the African continent, the increasing trendlines of climate change, with hotter weather expected every year, will surely exacerbate challenges for this region, one characterized by water scarcity, dry seasons, and infrastructural challenges in predicting unexpected climate hazards (e.g., downpours that cause floods).

Nexus Interdependencies and Systemic Pressures

The EWF nexus in East Africa involves profound intersectoral dependencies, leading to critical trade-offs, particularly between agriculture and hydropower, as well as between domestic water requirements and irrigation. Both opportunities and challenges stem from these interconnections, which have enduring implications for the region’s sustainable development. For the EWF nexus, climate change poses a significant threat and shakes the stability of the nexus. It creates cascading shocks for all three sectors simultaneously. Extreme weather events are posing a continuous threat to East Africa. Erratic rainfall, droughts, floods, and spikes in the temperature are posing significant threats to the nexus. It has simultaneously disrupted water availability, food production, and energy generation. The overall issue is amplifying social and economic vulnerabilities.

The EWF nexus not only faces environmental and technical challenges but also deeply embedded issues related to social structures. Rural populations, pastoralists, women, and other marginalized populations are excluded from decision-making processes that affect their vital access to critical resources. It further perpetuates social exclusion and embeds inequalities in the social structure. Continuation of such discrimination can undermine long-term equity and the effectiveness of the EWF nexus. In the nexus, a major social dimension is gender disparities. In food preparation, water collection, small-scale agriculture, and energy generation, the women’s labor force plays a significant role. Still, they face systemic barriers in accessing credit, land, and energy technologies, among others. Women laborers spend a significant number of hours collecting water and firewood, but their opportunities for income and education are lacking. In biomass use, they are disproportionately affected and exposed to indoor air pollution. It highlights the physical impact of fuel collection. Participatory governance frameworks are required to address these social dimensions.

Incorporate Nexus Thinking into National Development Plans

Adequate identification and addressing of the multifaceted challenges of the Energy-Water-Food Nexus in East Africa requires coordinated, inclusive, and forward-thinking policy actions. The interdependence character of such industries mandates that decision-makers move beyond siloed planning and adopt a well-rounded, nexus-oriented governance model. This study provides some actionable recommendations, centered on strategic directions to national and regional actors, to improve sustainability, socio-economic development, and resilience throughout East Africa.

The governments in East Africa should place nexus thinking at the center of national development strategies. Conventional planning methods tend to segregate resource sectors, which leads to inefficiency, redundancy of efforts, and lost synergies. Through an approach based on nexus, the governments will be able to give preference to projects that create benefits within the water, energy, and food systems. The integration of nexus frameworks can also support countries in achieving multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) simultaneously, including SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), and SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy).

While national development plans are crucial, the integration of the EWF nexus should encompass the entire continent, with the African Union (AU) serving as the central entity in this implementation framework. As previously noted, population growth, climate change, and economic shifts are occurring within the region, with infrastructural development remaining a primary objective of governments, regional development organizations, and continental institutions. At the continental level, the African Union’s Agenda 2063 strategy framework outlines the continent’s socioeconomic development goals for the next 50 years. Agenda 2063 aims to create a “continent with free movement of people, goods, capital, and services and infrastructure connections.”[26] Under Agenda 2063, improved water, energy, and food security are at the core of Africa’s development agenda and serve as prerequisites to unlocking economic development on the continent, ensuring a brighter future for member states.[27]

Conclusion

As climate stress intensifies and regional populations increase, the interdependence of these crucial sectors becomes increasingly apparent. In this broader context, it is noteworthy to state that isolated growth in one field, whether it be water access, agriculture, or energy supply, can be destabilized if not associated with the others.

The development of the East African Energy-Water-Food (EWF) nexus is also a daunting but exceptional prospect. For the economic transformation, rapid population growth and urbanization, climate change, and the interlinkages of water, energy, and food in East Africa, it is becoming increasingly inescapable that these systems are tightly linked to one another. A classic method for treating these sectors in isolation is no longer tenable in an era of climate-induced water scarcity that prevents agricultural productivity, blocks the flow of energy to drive irrigation and food processing, and hinders hydropower potential due to agricultural pollution of water.

East African countries that integrate their governance to acknowledge the circular nature of water, energy, and food systems will not only enable the efficient utilization of resources but also increase resilience and promote equitable development. Such a strategy involves transitioning from sectoral silos to inter-sectoral coordination through integrated policies and investments in agriculture, energy, and water management that link toward a common target of sustainability.

[1] World Meteorological Organization (WMO), “State of the Global Climate 2024,” WMO-No. 1368, World Meteorological Organization, 2025a, https://library.wmo.int/records/item/69455-state-of-the-global-climate-2024.

[2] World Meteorological Organization (WMO), “State of the Climate in Africa 2024,” WMO-No. 1370, World Meteorological Organization, 2025b, https://library.wmo.int/records/item/69495-state-of-the-climate-in-africa-2024.

[3] Maryam Haji, Sarah Namany, and Tareq Al-Ansari, “Strengthening Resilience: Decentralized Decision-making and Multi-criteria Analysis in the Energy-water-food Nexus Systems,” Frontiers in Sustainability 5 (May 2024), https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2024.1367931.

[4] World Meteorological Organization (WMO), “State of Climate in Africa Highlights Water Stress and Hazards,” September 8, 2022, https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/state-of-climate-africa-highlights-water-stress-and-hazards.

[5] Anadolu Agency, “Eastern Africa Suffers Worst Drought in 40 Years: IGAD,” Daily Sabah, April 12, 2022, https://www.dailysabah.com/life/environment/eastern-africa-suffers-worst-drought-in-40-years-igad.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Faith Mulwa, Zhuo Li, and Fangnon Firmin Fangninou, “Water Scarcity in Kenya: Current Status, Challenges and Future Solutions,” OALib 8, no. 1 (2021): 1–15, https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1107096.

[8] “SWP Water Resources Profile Series Launch,” Winrock International, July 21, 2021, https://winrock.org/swp-water-resources-profile-series-launch/.

[9] “Water in Agriculture : Towards Sustainable Agriculture (English),” World Bank Group, October 20, 2021, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/875921614166983369.

[10] Ibid.

[11] IEA, IRENA, UNSD, World Bank, and WHO, “Tracking SDG 7: The Energy Progress Report 2025,” World Bank, 2025, https://trackingsdg7.esmap.org/.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Munsu Kang, “Energy Accessibility and Green Energy Cooperation in East Africa,” SSRN Electronic Journal, March 2024, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4749679.

[14] “Hydropower Development in Ethiopia to Attain Sustainable Growth,” Hydropower, May 24, 2018, https://www.hydropower.org/blog/blog-hydropower-development-in-ethiopia-to-attain-sustainable-growth.

[15] Mohammed Takase, Rogers Kipkoech, and Paul Kwame Essandoh, “A Comprehensive Review of Energy Scenario and Sustainable Energy in Kenya,” Fuel Communications 7 (June 2021): 100015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfueco.2021.100015.

[16] United Nations, “International Day of Clean Energy (26 January),” 2025, https://www.un.org/en/observances/clean-energy-day.

[17] Hüseyin Çiloğlu, “Empowering Africa Through the Water-energy-food Nexus: A Path to Sustainability,” Energy Connects. July 10, 2024, https://www.energyconnects.com/opinion/thought-leadership/2024/july/empowering-africa-through-the-water-energy-food-nexus-a-path-to-sustainability/.

[18] “Global Report on Food Crises for East Africa 2024 Snapshot,” ICPAC, April 24, 2024, https://www.icpac.net/publications/global-report-on-food-crises-for-east-africa-2024-snapshot/.

[19] FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO, “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2025,” https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/the-state-of-food-security-and-nutrition-in-the-world-2025.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Katherine Snyder, Pauline Muindi, Colleta Khaemba, Pieter Rutsaert, Judy Mutegi, Francis Omondi, and Jason Donovan, “Wheat in Kenya: Toward Self-sufficiency or Toward Broader Development Goals,” Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 9 (February 2025), https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2025.1532337.

[23] United Nations, World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results. Statistical Papers – United Nations. Series A, Population and Vital Statistics Report, https://doi.org/10.18356/9789211065138.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Andrew Stanley, “African Century: A Demographic Transformation in Africa Has the Potential to Alter the World Order,” International Monetary Fund, September 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2023/09/PT-african-century.

[26] Gareth B. Simpson, Graham P. W. Jewitt, Tafadzwanashe Mabhaudhi, Cuthbert Taguta, and Jessica Badenhorst, “An African Perspective on the Water-Energy-Food Nexus,” Scientific Reports 13, no. 1 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43606-9.

[27] Ibid.