In May 2025, TRENDS Research & Advisory, through its office in Canada, convened a global conference in Montreal examining the role of advanced technology in the contemporary geopolitical landscape. The conference was organized within the framework of the annual forum of the Francophone Association for Knowledge. Drawing on the key insights and outcomes of this conference, as well as on a carefully selected body of academic and scientific literature, this study explores the most significant dynamics likely to shape the world in the coming years.

The period beyond 2026 represents a structural inflection point in the evolution of the international system, not as the result of a single political or military event, but as the cumulative effect of deep and accelerating technological transformations. These transformations have fundamentally altered the nature of power, sovereignty, and global competition. Technology is no longer a neutral instrument used by states to enhance pre-existing capabilities; it has become a governing structure that organizes economic production, political authority, security practices, and social relations while exerting a direct influence on the global balance of power.

Within this emerging context, technological systems, most notably artificial intelligence, advanced data infrastructures, smart manufacturing, biotechnology, space technologies, and hyperconnectivity, no longer operate in isolation. Instead, they form an integrated technological ecosystem that reshapes how power is accumulated, exercised, and contested at both national and transnational levels. As a result, contemporary geopolitical analysis can no longer rely exclusively on traditional categories such as territory, natural resources, or military balance. While these factors remain relevant, they are increasingly insufficient to explain patterns of dominance, dependency, and strategic influence in the post-2026 world.

This transformation calls for a renewed analytical framework, here described as technogeopolitics. Unlike conventional approaches that treat technology as a sectoral or auxiliary variable, technogeopolitics conceptualizes advanced technology as a structural determinant of geopolitical change. Adopting this framework, the present study examines how advanced technologies are reshaping global competition, redefining sovereignty, and reconfiguring the geopolitical map beyond 2026.

This study adopts a cumulative analytical approach aimed at unpacking contemporary geopolitical transformations through their underlying structural layers. It begins by redefining power, moving beyond traditional material foundations toward algorithmic and knowledge-based forms of influence, and conceptualizes technology as a sovereign infrastructure reshaping state authority. The analysis then examines technological convergence and accelerated innovation, with particular emphasis on artificial intelligence as the cognitive core of the emerging international order. It further extends to smart manufacturing, biotechnology, and the cyber and space domains before addressing digital sovereignty and competing governance models, offering an integrated framework for understanding the reconfiguration of the international system beyond 2026.

1. Structural Transformation of Geopolitical Power

a. From Material Power to Algorithmic Power

Historically, geopolitical power has been anchored in material foundations: territorial control, population size, access to natural resources, and military capability. While these elements continue to matter, they no longer fully account for the growing disparities in influence among states. In the post-2026 world, algorithmic and knowledge-based power has emerged as a decisive factor in determining strategic advantage.

The ability to collect, process, and operationalize vast amounts of data through advanced artificial intelligence systems has become a central condition of geopolitical effectiveness. Power is increasingly measured not by the sheer size of armed forces but by the speed of information processing, predictive capacity, and the ability to control informational environments. Algorithms now function as instruments of authority, shaping decision-making processes, strategic foresight, and behavioral outcomes across societies.

b. Technology as a New Sovereign Infrastructure

Technology has ceased to be external to politics. It now constitutes a sovereign infrastructure that directly affects a state’s capacity to perform its core functions, including security provision, economic governance, public administration, and legal regulation. States that rely heavily on foreign digital platforms, cloud infrastructures, or externally controlled AI systems face structural vulnerabilities that undermine strategic autonomy, even if formal sovereignty remains intact.

This reality raises fundamental questions about sovereignty in the digital age. Control over data flows, computational infrastructure, and algorithmic architectures has become as critical as control over borders and airspace in earlier eras.

2. Technological Convergence and Accelerated Innovation as Geopolitical Drivers

a. From Isolated Sectors to Integrated Technological Systems

One of the defining features of the contemporary technological landscape is the accelerating convergence between previously distinct domains: artificial intelligence, high-speed telecommunications, materials science, biotechnology, and behavioral sciences. This convergence generates integrated technological systems whose collective impact far exceeds the sum of their individual components.

Such systems lower barriers to entry for new actors while simultaneously rewarding those capable of coordinating multiple technological domains within a coherent national or corporate strategy. As a result, geopolitical advantage increasingly depends on systemic integration rather than isolated technological breakthroughs.

b. Shrinking Innovation Cycles and Strategic Pressure

Innovation cycles that once unfolded over decades are now compressed into a few years. This acceleration imposes unprecedented strategic pressure on policymakers, as technological lag increasingly translates into geopolitical vulnerability. In this context, competition over global technical standards, intellectual property regimes, and data governance frameworks has become a central arena of indirect geopolitical rivalry.

3. Artificial Intelligence as the Core of the New Geopolitical Order

a. AI as a General-Purpose Infrastructure

Artificial intelligence has emerged as the cognitive infrastructure of the post-2026 world. As a general-purpose technology, AI penetrates all strategic sectors, including defense, intelligence, healthcare, education, finance, and diplomacy. The ability to develop sovereign AI models, control training data, and manage computational resources has become a defining criterion of national power.

b. Unequal Distribution and the Expansion of Geopolitical Asymmetry

Advanced AI capabilities are concentrated in a small number of states and large technology corporations. This concentration deepens geopolitical asymmetries and produces new forms of dependency, particularly for states lacking large datasets, advanced computing infrastructure, or skilled human capital. Technological inequality thus becomes a structural feature of the international system.

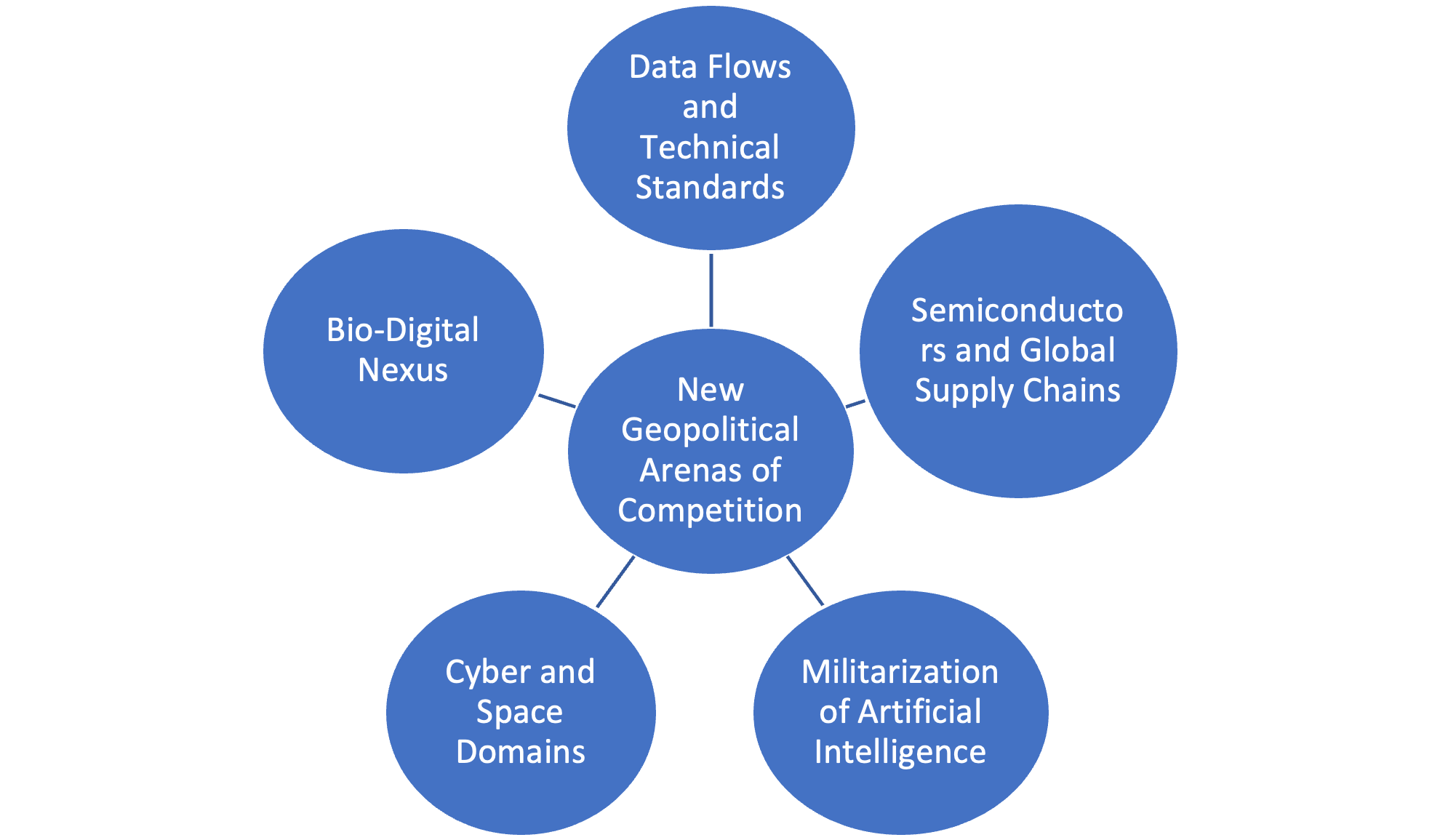

c. Militarization of AI and Escalation Risks

The integration of AI into military systems, ranging from autonomous weapons to decision-support platforms, has transformed the strategic landscape. While these systems promise operational efficiency, they also increase the risks of unintended escalation, algorithmic error, and loss of human control. Ethical and regulatory frameworks remain fragmented, reinforcing global technological fragmentation.

4. Smart Manufacturing and Supply Chains as Hidden Geographies of Power

Advanced manufacturing technologies, including additive manufacturing (3D Printing) and AI-enabled factories, are reshaping global value chains. Traditional comparative advantages based on labor costs or geographic proximity are increasingly being replaced by innovation capacity and control over technical knowledge.

Semiconductors, in particular, have become a strategic geopolitical resource. Control over their production and supply chains is now directly linked to national security, economic resilience, and technological sovereignty. Moreover, the expansion of AI has intensified pressure on energy systems, creating a new interdependence between technological security and energy security.

5. Biotechnology and the Bio-Digital Nexus

Biotechnology has evolved into a major geopolitical variable, influencing public health security, food systems, and demographic resilience. Advances in gene editing, synthetic biology, and AI-assisted drug discovery extend geopolitical competition into the biological domain.

The convergence of digital and biological systems—the bio-digital nexus—raises profound ethical and security challenges. Dual-use research, biosecurity risks, and unequal access to advanced therapies complicate governance and exceed the regulatory capacity of individual states, highlighting the need for new international frameworks.

6. Space and Cyberspace as New Geopolitical Arenas

a. Outer Space as Strategic Extension

Outer space has become a critical domain of geopolitical competition. Satellite systems underpin military operations, global communications, navigation, and economic activity. The integration of AI into space operations further amplifies strategic dependence on orbital infrastructure.

b. Cyberspace as the Fifth Battlespace

Alongside land, sea, air, and space, cyberspace has emerged as a fully operational domain of conflict. Cyberattacks, information warfare, and cognitive manipulation increasingly target critical infrastructure, political institutions, and social cohesion, making cybersecurity an essential component of national sovereignty.

7. Digital Platforms and Non-State Geopolitical Actors

Large technology corporations have evolved into quasi-geopolitical actors, exercising influence over data flows, information ecosystems, and public discourse. Their power often rivals that of states, complicating traditional notions of sovereignty and regulation.

Simultaneously, digital environments enable non-state ideological actors to conduct transnational narrative warfare, leveraging AI-driven disinformation and algorithmic amplification to shape perceptions and destabilize political systems.

8. Digital Sovereignty, Governance, and Strategic Fragmentation

Sovereignty in the post-2026 world extends beyond territory to encompass data, digital infrastructure, and knowledge systems. States face a structural dilemma: how to regulate digital space and protect sovereignty without stifling innovation. Divergent governance models, particularly those of the United States, China, and the European Union, reflect competing visions of technological order and political authority.

Conclusion

What is unfolding beyond 2026 is not a marginal adjustment in the instruments of power but a structural transformation in the logic of the international system. Advanced technology has moved from the periphery of politics, economics, and security to their very core, becoming the framework through which sovereignty, strategic autonomy, and political agency are redefined. The convergence of artificial intelligence, biotechnology, advanced manufacturing, space technologies, and cyberspace is reshaping geopolitical interaction by blurring established distinctions between civilian and military domains, national and transnational spaces, and human and algorithmic decision-making. This trend is observable across diverse state contexts, including the incorporation of AI into military planning and intelligence analysis in the United States and Israel, as well as broader civil-military innovation integration strategies pursued by China and South Korea.

In this evolving environment, geopolitical competition is increasingly structured around control over data, computing capacity, technological standards, and innovation ecosystems rather than territorial expansion or conventional force projection. The strategic rivalry between the United States and China over semiconductors, cloud infrastructure, and AI governance illustrates how technological infrastructures have become central arenas of power competition. At the same time, the European Union represents a distinct model of influence, seeking to translate regulatory capacity and normative frameworks in data protection and artificial intelligence into geopolitical leverage. These differentiated strategies highlight that power disparities among states are now shaped less by geography or military scale than by the ability to produce, govern, and strategically mobilize technological knowledge.

Technological inequality has consequently emerged as a structural feature of the international system. While advanced economies consolidate their positions through innovation and standard-setting, many states in the Global South remain structurally dependent on external technologies, platforms, and infrastructures. This asymmetry generates new forms of dependency that are economic, political, and strategic in nature, with long-term implications for global stability.

The post-2026 context thus confronts states with a shared dilemma: how to reconcile technological sovereignty and security with openness, innovation, and economic integration. Divergent national responses illustrate competing governance paradigms. The United States continues to emphasize market-driven innovation and private-sector leadership, China advances a state-centered approach linking technological sovereignty to political control, and the European Union promotes a regulatory model grounded in ethics, rights, and accountability. These approaches reflect fundamentally different conceptions of authority and social order, contributing to a progressively fragmented international environment organized around competing technological blocs.

The reconfiguration of the geopolitical map beyond 2026 will therefore depend on the capacity of states to develop coherent technological strategies that move beyond passive adoption toward sovereign innovation and institutional integration. Emerging examples include national AI strategies in Canada, France, and the United Arab Emirates, which seek to balance competitiveness with ethical governance, as well as industrial policies in Japan aimed at securing strategic positions within global semiconductor value chains. Beyond national efforts, effective international coordination will be essential to manage risks linked to AI militarization, bio-digital convergence, and cyber escalation.

| State / Model | Core Approach | Key Characteristics | Geopolitical Function |

| United States | Market-driven technological model | Corporate leadership, private-sector innovation, dominance in AI and cloud infrastructure | Projection of power through innovation ecosystems and global platform control |

| China | State-centered technological sovereignty | Civil–military fusion, centralized planning, political control of technology | Consolidation of strategic autonomy and alignment of technology with state power |

| European Union | Regulatory and normative governance | Ethics-based regulation, protection of rights, standard-setting authority | Transformation of regulatory capacity into geopolitical influence |

Absent such a coordinated strategic vision, advanced technology risks amplifying fragmentation and systemic volatility rather than fostering shared prosperity. If, however, technological transformation is embedded within political and institutional frameworks that prioritize human agency, accountability, and ethical restraint, it may still serve as the basis for a more resilient, balanced, and adaptive international order in the decades ahead.

References

Graham Allison, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017).

Benjamin H. Bratton, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016).

2026: The Tech Tipping Point (Connected World, 2025), https://connectedworld.com/2026-the-tech-tipping-point/.

Dubai Future Foundation, The Global 50: Future Opportunities 2025 (Dubai: Dubai Future Foundation, 2025), https://www.dubaifuture.ae/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/The-Global-50-2025-Eng.pdf.

European Commission, Proposal for a Regulation Laying Down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) (Brussels, 2021), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/.

Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman, “Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion,” International Security 44, no. 1 (2019): 42–79.

Gartner, “Gartner Identifies the Top Strategic Technology Trends for 2026,” Gartner Newsroom, October 20, 2025, https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2025-10-20-gartner-identifies-the-top-strategic-technology-trends-for-2026.

Heptagon Capital, Key Themes for 2026 and Beyond (London: Heptagon Capital, 2025), https://heptagon-capital.com/key-themes-for-2026-and-beyond.

Henry A. Kissinger, Eric Schmidt, and Daniel Huttenlocher, The Age of AI and Our Human Future (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2021).

Joseph S. Nye Jr., Do Morals Matter? Presidents and Foreign Policy from FDR to Trump (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021).

UNESCO, Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence (Paris: UNESCO, 2021), https://www.unesco.org/.

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (New York: PublicAffairs, 2019).

Technogéopolitique : quelle place les technologies occupent-elles dans les relations internationales? 92e Congrès de l’Acfas, https://www.acfas.ca/archives/evenements/congres/activites/88639.

Wael Saleh, “Technogéopolitique: le nouvel échiquier des puissances,” Le Devoir, August 23, 2025, https://www.ledevoir.com/opinion/idees/911496/technogeopolitique-nouvel-echiquier-puissances.