Welcome to the inaugural edition of the TRENDS Med-MENA Nexus Report, a monthly analytical platform from TRENDS Research & Advisory dedicated to unpacking how Italy and Southern Europe are reshaping their strategic engagement with the Mediterranean, the Gulf, and the broader Indo-Mediterranean arena.

At a moment of profound geopolitical flux—marked by shifting trade corridors, accelerating defense industrialization, and the mounting pressures of the global energy transition—Southern Europe has moved from the periphery to the center of several emerging strategic dynamics. Italy, in particular, is deepening its role as a connector between Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, leveraging its geography, industrial base, and diplomatic outreach to shape new patterns of cooperation.

This inaugural report highlights three domains where this transformation is most visible: the reconfiguration of connectivity through the India–Middle East–Europe Corridor (IMEC); the evolution of Euro–Gulf defense partnerships from traditional procurement to joint industrial ecosystems; and the emergence of a new Mediterranean energy architecture connecting European climate ambitions with MENA and Gulf capabilities.

Taken together, these trends reveal a rapidly changing landscape—one in which Southern Europe is not merely reacting to global shifts but helping define the contours of a new, interconnected strategic era.

Chapter 1. IMEC and Europe’s New Connectivity Axis

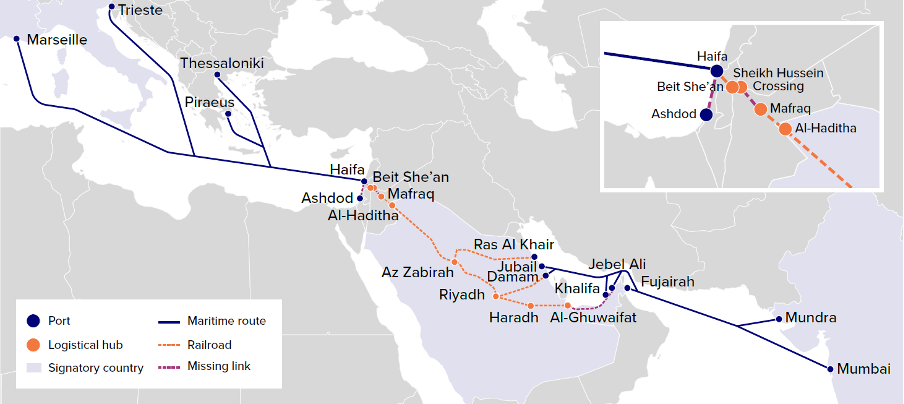

The India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) is emerging as one of the most strategically significant connectivity initiatives of the current global cycle, linking South Asia, the Gulf, and Southern Europe, as shown in Map 1. The IMEC is conceived as a multimodal system of maritime routes, energy infrastructure, digital corridors, and—eventually—transcontinental rail. Rather than a single “shovel-ready” project, IMEC is designed as a phased, modular framework under which different but interoperable components are developed over time. Its implementation is advancing at asymmetric speeds, yet the overall trajectory is clear: the Indo-Mediterranean space is consolidating as a new axis of global connectivity, and Southern Europe is positioning itself as its natural European anchor.

Map 1: India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) Proposed Routes

Source: The White House 2023, Fact Sheet: India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, The White House, 9 September, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/09/09/fact-sheet-india-middle-east-europe-economic-corridor/

Since the official announcement of the initiative at the G20 Summit in New Delhi in September 2023, the three segments of the corridor have progressed unevenly. The eastern section—connecting India with Gulf ports—has advanced rapidly, benefiting from New Delhi’s Look West Policy and substantial port investments supported by Emirati actors such as DP World, as highlighted by CESI’s recent analysis of IMEC’s implementation dynamics.[1] By contrast, the central rail segment linking the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel remains stalled amid regional tensions and uncertainty over post-war Gaza, the future of Riyadh–Tel Aviv normalization, and broader US–Iran diplomacy. While political conditions are not yet conducive to realizing the land bridge, the maritime dimension of IMEC offers an immediately workable alternative. Reliance on traditional sea routes also underscores the non-confrontational nature of the project, which aims to diversify rather than replace existing trade channels and enhance the resilience of global supply chains.

It is in this evolving context that Southern Europe—Italy, Greece, and France in particular—is asserting itself as IMEC’s prospective European terminal. Trieste, Thessaloniki, and Marseille each offer distinct logistical, regulatory, and industrial advantages as entry points into the EU market. Trieste stands out for its unique combination of port depth, rail intermodality, and proximity to Central and Eastern Europe. Its integration into the Baltic–Adriatic Corridor—a core north–south axis of the EU’s TEN-T network linking Baltic ports with the Adriatic—and emerging synergies with the Three Seas Initiative—a regional platform connecting 12 EU member states between the Baltic, Adriatic, and Black Seas through infrastructure, energy, and digital projects—reinforces its potential role as the continental extension of the Indo-Mediterranean corridor.[2] Thessaloniki offers immediate access to the Balkans and the Danube basin, while Marseille provides critical energy and digital infrastructure, including LNG terminals and major subsea cable landing points. The presence of European-backed initiatives such as Global Gateway—the EU’s flagship connectivity strategy to finance sustainable infrastructure with trusted partners—further strengthens the potential of these ports to serve as IMEC’s western anchor.[3]

Italy has moved with particular determination to position itself at the forefront of IMEC’s European dimension. Throughout 2024–2025, Rome invested heavily in revitalizing its partnership with India and deepening ties with Gulf states, recognizing that the corridor offers a rare opportunity to bind together its Mediterranean, African, and Indo-Pacific policies.[4] Italy’s appointment of Ambassador Francesco Maria Talò as Special Envoy for IMEC, alongside the creation of the first parliamentary intergroup dedicated to the corridor, signals sustained political commitment across institutions.[5] The Foreign Ministry has framed IMEC as one of the main vectors of Italy’s external projection, situating it within a broader strategy of economic diplomacy, energy diversification, and support for Europe’s “connectivity sovereignty.”[6] In early December 2025, Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani’s visit to New Delhi further reinforced this trajectory, with IMEC featuring prominently in discussions on maritime connectivity, digital infrastructure, and the future of Euro–Indo-Pacific cooperation.[7]

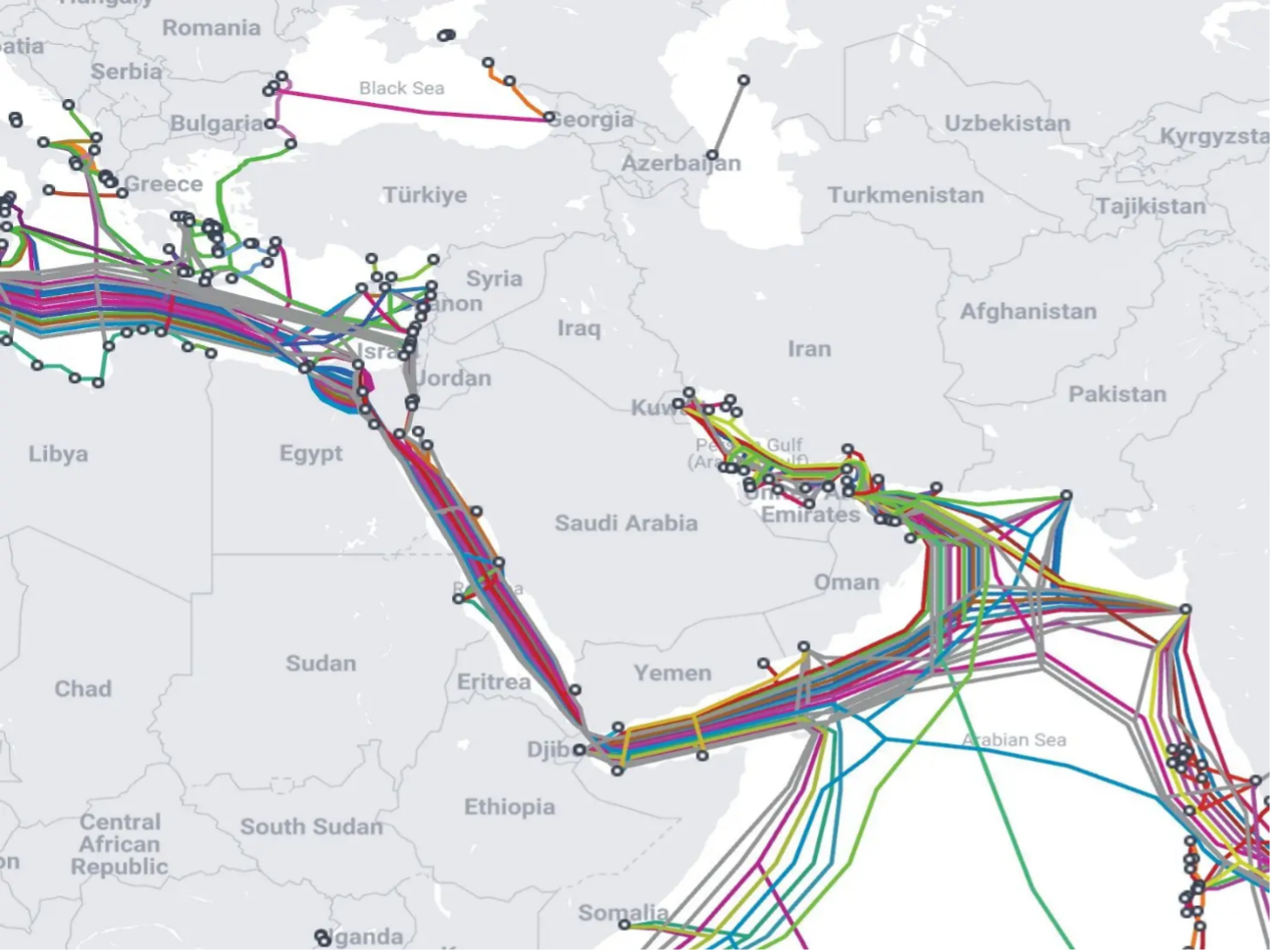

Rome’s maritime diplomacy has also intensified. During the India Maritime Week in Mumbai (October 2025), Deputy Minister Edoardo Rixi and Indian Minister Sarbananda Sonowal established a bilateral working group to coordinate maritime and logistical cooperation along IMEC, complemented by a forthcoming memorandum of understanding between Italian and Indian port authorities.[8] The initiative aligns with Italy’s Piano Italia 2032, which mobilizes over €200 billion to modernize national infrastructure—including major upgrades to Genoa and Trieste and cross-border projects such as the Brenner Base Tunnel and the Turin–Lyon high-speed link.[9] In parallel, Italy’s outreach to Qatar and the UAE links IMEC’s Indo-Mediterranean axis to Gulf investment in strategic sectors such as mobility, logistics, energy, and data connectivity. In keeping with the themes of connectivity and resilience, new subsea cable routes (Map 2) are planned in order to reroute traffic around the Red Sea and mitigate the impact of regional disruptions.[10]

Map 2: Middle East – Eastern Mediterranean Submarine Cable Map

Source: TeleGeography 2023, Submarine Cable Map, TeleGeography, https://www.submarinecablemap.com/

Furthermore, Italy is embedding IMEC within a wider set of regional strategies. The corridor dovetails with the Mattei Plan for Africa, which prioritizes energy transition, digital infrastructure, and long-term development partnerships—areas that significantly overlap with IMEC’s planned clean-hydrogen pipelines and subsea data cables.[11] The European Union has explicitly recognized this synergy, linking IMEC and the Mattei Plan to Global Gateway and to the broader European Economic Security Strategy. In parallel, the EU–India Free Trade Agreement (FTA) negotiations have entered a decisive phase, with both sides seeking to anchor their economic relationship in rules-based trade, supply-chain security, and industrial resilience—an outcome that would provide an enabling framework for IMEC’s full operationalization.[12]

As regional diplomacy intensifies around Gaza, the Gulf, and the Red Sea, Italy’s role as a Mediterranean connector has become more visible. Rome’s participation in the 46th GCC Summit held in Bahrain in December 2025—the first invitation extended to a non-GCC leader since 2016—has been widely interpreted as a recognition of Italy’s capacity to act as a bridging actor between Europe and the Arabian Peninsula.[13] In Manama, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni explicitly highlighted IMEC as a transformational connectivity spine linking India, Gulf ports, Europe, and eventually the United States; Meloni proposed a GCC–Med Summit in Rome to institutionalize dialogue on connectivity, energy, and regional stability.[14] Italy is simultaneously pushing a new energy diplomacy that connects Europe, Africa, and the Gulf under the Mattei Plan, guided by a principle of technological neutrality that seeks to mobilize “all available and emerging technologies” in support of the energy transition.[15]

Chapter 2 – Localization and Co-Production: A New Era in Euro–Gulf Defense

Europe’s defense relationships with GCC states are entering a new strategic phase. While the United States remains the region’s primary security guarantor—responsible for forward deployment, integrated air and missile defense, and large-scale sustainment—European countries are steadily carving out a complementary role rooted in industrial cooperation, technology transfer, and defense localization. What was once a predominantly supplier-driven relationship is evolving into a balanced, multi-directional partnership in which European firms help Gulf states develop indigenous capabilities while Gulf investments, in turn, reinforce Europe’s own defense-industrial base.

This shift is measurable, with Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimates for 2020–24 showing that although the United States still accounted for half of all arms imports to MENA, European suppliers collectively represented a substantial share: Italy ranked second overall with 12%, followed by France with 9.7%, Germany with 7.6%, and Spain with 3.9%. Country-by-country patterns confirm Europe’s embedded role: Saudi Arabia sourced 10% of its imports from Spain and 6.2% from France; Qatar relied on Italy for 20% and France for 14%; Kuwait acquired 29% of its systems from Italy.[16] Arms import relationships of GCC countries between 2020 and 2024 (Chart 1 below) show similar patterns, with US exports leading the arms supply relationship for almost all GCC countries, generally followed by exports from Italy, France, and the UK.

Chart 1: Top Selected Arms Suppliers to GCC States (2020–24)

Source: TRENDS processing of Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) 2024, SIPRI Arms Transfers Database: Top Selected Arms Suppliers to GCC States (2020–24), https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers

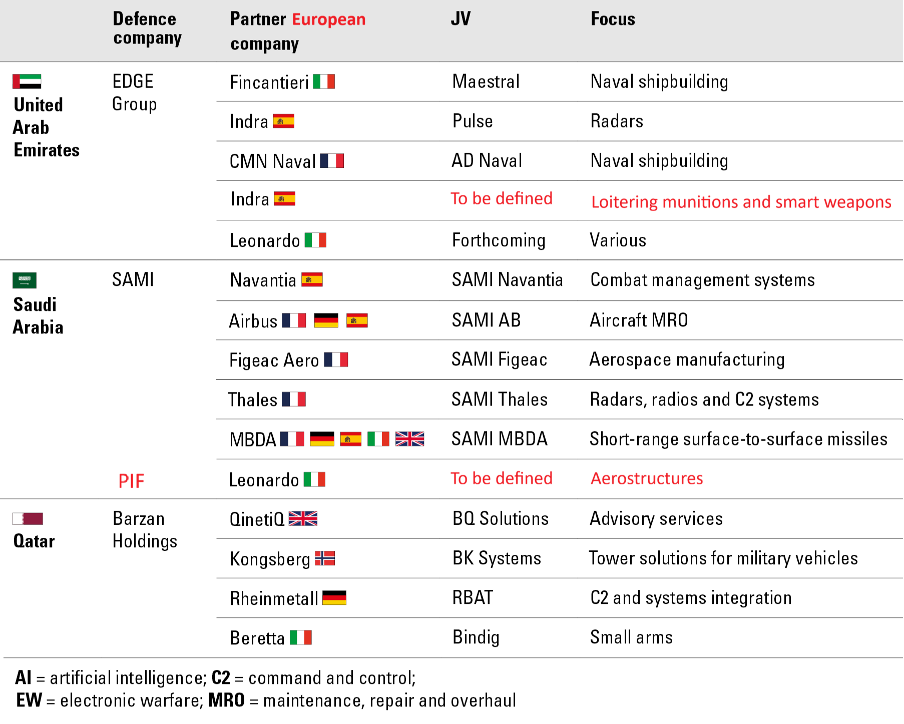

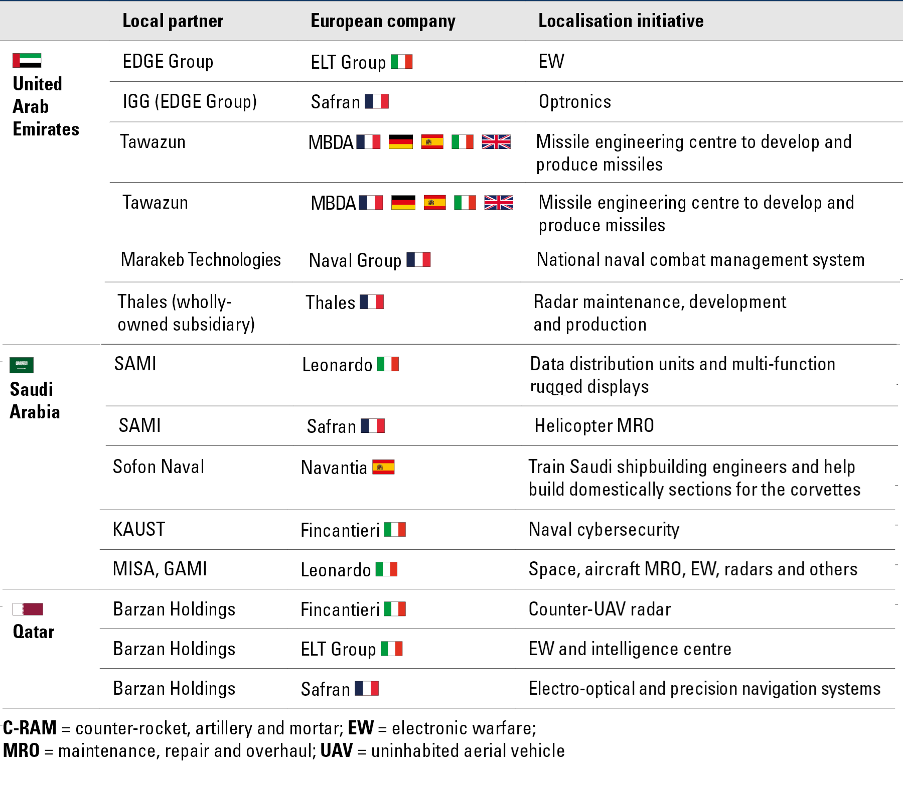

Yet statistics alone cannot fully capture how profoundly the relationship is changing. Since around 2018, and more sharply over the last three years, defense industrialization leveraging joint ventures has become a pillar of Gulf national strategies (Table 1). In the UAE, institutions such as Tawazun Council, EDGE Group, and Calidus have emerged as central actors coordinating defense procurement, workforce development, and joint ventures with international firms. In Saudi Arabia, this role is assumed by the General Authority for Military Industries (GAMI) and Saudi Arabian Military Industries (SAMI)—the two pillars through which Vision 2030 aims to localize at least 50% of defense expenditure by the end of the decade. European companies, particularly in Italy, France, and Spain, have adapted to these rapidly evolving priorities by shifting from export-driven engagements to long-term partnerships centered on co-development, skills transfer, and embedded production.[17]

Table 1: GCC Joint Ventures with Selected European Partners

Source: International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) Data: GCC defense joint ventures with selected European partners, 2018–2025, in The Military Balance, IISS, https://www.iiss.org/publications/the-military-balance

Italy’s trajectory exemplifies this transformation. As Italian Ambassador Carlo Baldocci recently underscored, Rome is “fully prepared to support the defense sector goals laid out in Vision 2030,” with Italian firms increasingly active in naval shipbuilding, helicopter manufacturing, cyber defense, and advanced surveillance technologies.[18] The strategic partnership signed in Al-Ula between Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni accelerated this dynamic, generating over €10 billion in agreements and prompting a surge of interest from Italian private industry. Meloni’s broader Gulf strategy—built on personal diplomacy, industrial deals, and a new regional architecture—has positioned Italy as a pivotal Southern European partner.[19]

These developments coincide with Italy’s expanding industrial footprint across the region. Fincantieri’s €5 billion naval program in Qatar—including the Al Zubarah-class corvettes, Musherib-class OPVs, and the Al Fulk LPD—combines high-end platforms with training and lifecycle support, reflecting a more holistic approach to defense cooperation. Defense company Leonardo’s role is even more emblematic of the shift toward localization.[20] Following a comprehensive cooperation framework signed in mid-2025, Leonardo and EDGE announced, at the Dubai Airshow, a major step toward launching a joint venture in Abu Dhabi in 2026, focused on multi-domain technologies spanning sensors, system integration, avionics, and electro-optics.[21] This regional presence was further reinforced during Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s participation in the 46th GCC Summit in Bahrain, where Fincantieri and ASRY (Arab Shipbuilding & Repair Yard) signed an industrial cooperation agreement aimed at co-designing and co-producing surface naval vessels of up to 80 meters for the Bahraini Navy and Coast Guard, as well as similarly sized offshore units.[22]

Spain has likewise emerged as a rising actor in Euro–Gulf defense cooperation. The establishment of PULSE NOVA, a joint venture between EDGE and Indra, has made Abu Dhabi a new hub for next-generation radar engineering and production.[23] In November 2025, Indra and EDGE expanded this cooperation through a Spain-based joint venture for loitering munitions and smart weapons—combining Indra’s European industrial base with EDGE’s rapid development model and operational experience.[24] This two-way flow of capital and technology illustrates how Southern Europe is becoming structurally integrated into Emirati-led innovation networks.

France, traditionally the leading European player in Gulf air and naval procurement, is similarly embedding its presence more deeply within local industrial frameworks. Beyond its landmark Rafale F4 deal with the UAE and longstanding ties with Qatar and Saudi Arabia,[25] a significant new step came with the creation of MBDA UAE, the multinational MBDA defense company’s first wholly-owned subsidiary outside Europe. The subsidiary will focus on missiles and loitering munitions and will absorb MBDA’s existing Missile Engineering Center in the UAE while expanding cooperation with EDGE, Calidus, and Tawazun Industrial Park. MBDA is simultaneously partnering with France’s ASB Group to establish local thermal-battery production, localizing a critical missile component “from A to Z.”[26] Other localization initiatives involving partnerships between European and GCC countries are illustrated below in Table 2.

Table 2: Selected Defense Localization Initiatives in GCC States 2018-2025

Source: International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) Data: Defense Localization Initiatives in GCC States 2018–2025, in The Military Balance, IISS, https://www.iiss.org/publications/the-military-balance

Finally, the evolving geography of the Eurofighter Typhoon illustrates the emergence of a truly interconnected Euro–Gulf defense ecosystem. The October 2025 agreement between the United Kingdom and Turkey for 20 new Typhoons—valued at $10.66 billion—was widely described as the largest British fighter export deal in a generation.[27] The Eurofighter—Europe’s most advanced combat aircraft—is coordinated through a consortium of Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK, which centralizes production and export decisions. Parallel negotiations with Qatar and Oman for the re-export of up to 24 in-service aircraft to Ankara reveal how Gulf operators now function as active enablers of regional industrial integration. London reportedly supports the Turkey–Qatar/Oman transfer, confident that Doha will offset any reduction in fleet numbers by ordering new aircraft—an outcome that would reinforce the entire Eurofighter production chain across the consortium.[28]

Altogether, these developments mark a decisive transition in Euro–Gulf defense ties. Europe is no longer merely supplying systems; it is co-designing them, producing them locally, and integrating Gulf partners into European R&D and export architectures. Southern Europe—in particular, Italy, France, and Spain—has become the industrial hinge of this new partnership, linking European innovation with Gulf localization ambitions and laying the foundations of a more interdependent and strategically resilient Euro–Gulf security order.

Chapter 3 – Energy Interdependence in the Mediterranean’s Green Transition

Europe’s ambition to build a greener and more ethically governed economy increasingly intersects with its structural dependence on energy imports from the Middle East and North Africa. The ongoing review of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD)[29] has become a test case for the EU’s ability to reconcile regulatory harmonization with the operational parameters of international energy supply chains. The directive aims to introduce mandatory due diligence procedures across environmental and human rights domains, potentially affecting upstream and midstream segments of cross-border energy trade. As trilogue discussions resumed in late October 2025[30] several energy-exporting partners underscored the importance of ensuring that emerging compliance obligations remain compatible with long-term contractual frameworks, capital-intensive project cycles, and the risk-allocation mechanisms underpinning LNG and pipeline agreements.

In its 5 December 2025 statement,[31] the Gulf Cooperation Council underlined the value of maintaining smooth trade and energy cooperation with the European Union, encouraging further dialogue to ensure that new requirements remain proportionate and compatible with shared economic objectives (GCC Secretariat). Rather than a point of friction, this evolving discussion highlights a broader structural task: integrating ESG-driven regulation into Europe’s diversification and energy security policies in a way that preserves the reliability of strategic supply chains while advancing sustainability goals.

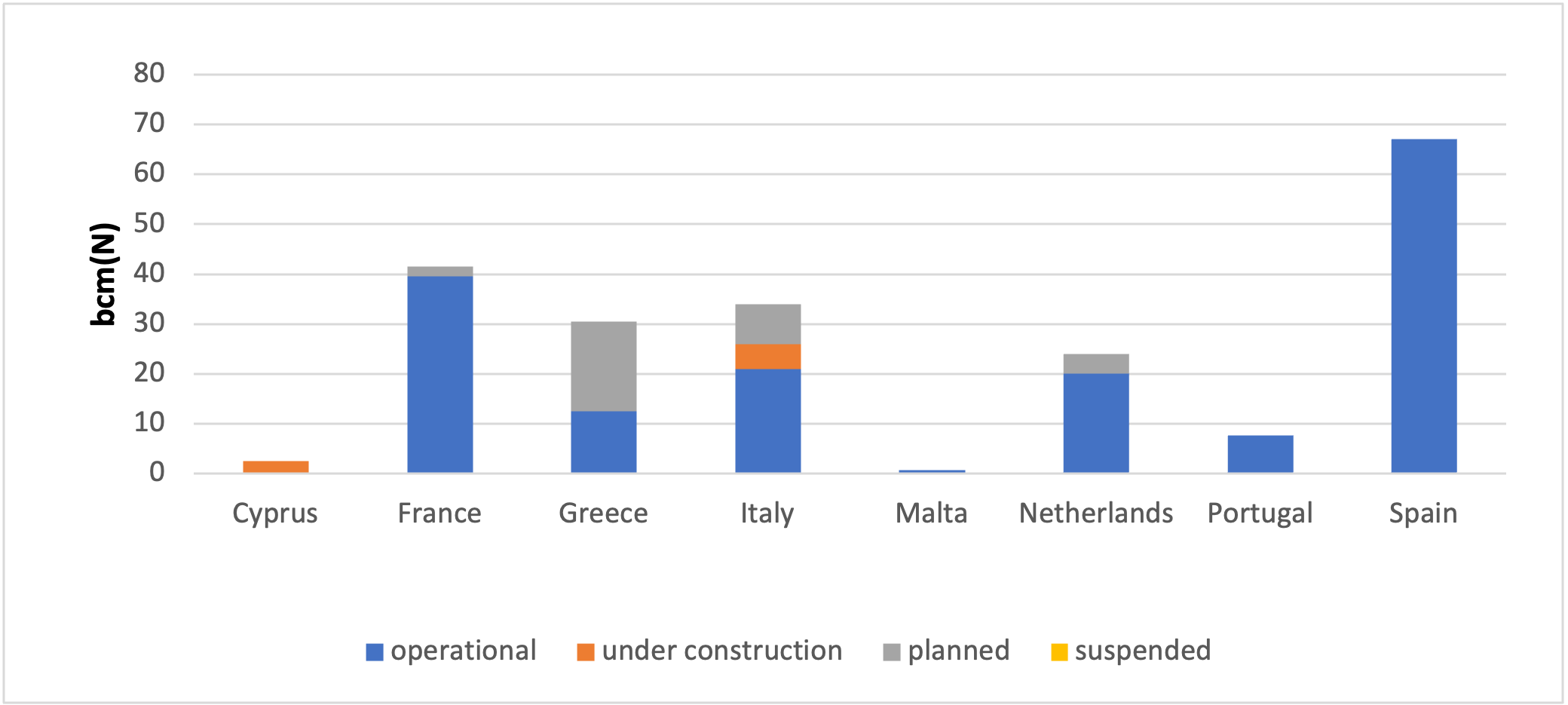

Southern Europe occupies a central position within this evolving regulatory and energy integration landscape. As Italy, Greece, Spain, and other Southern European countries become the primary gateways for LNG imports into the continent (Chart 2 below), they face the dual responsibility of ensuring compliance with EU sustainability frameworks while maintaining the stability, affordability, and operational continuity of energy supply. This balancing act is reshaping the geopolitical and infrastructural geography of the Mediterranean. On the one hand, Southern Europe must uphold the EU’s climate narrative; on the other, it must recognize that its decarbonization depends on continued energy integration with the MENA region. This duality is driving a new phase of strategic cooperation, grounded not only in import flows but in shared energy transition infrastructures, joint investment frameworks, and long-term industrial alliances.

Chart 2: Annual LNG Regasification Capacity of Selected Import Terminals

Source: Gas Infrastructure Europe (GIE) 2024, LNG terminals by status in Europe, GIE LNG Database, https://www.gie.eu/

In January 2025, Italy and Saudi Arabia signed a landmark partnership covering green hydrogen, low-carbon fuels, methane emissions reduction, grid modernization, and carbon capture technologies—an agreement framed as a pillar of Europe’s future energy resilience.[32] In parallel, QatarEnergy and Italy’s ENI sealed a 27-year LNG agreement ensuring stable deliveries well into the 2050s—a period in which Europe’s decarbonization plans will require both renewable expansion and transitional system stability.[33] Far from signaling a contradiction, these deals underscore a reality often under-acknowledged in Europe’s climate discourse: the green transition requires long-term stability in conventional energy supplies, even as new sources and technologies emerge.

At the infrastructural level, a series of new Mediterranean-centered projects is reinforcing this trend. The Italy–Greece subsea interconnector[34] and the Italy–Albania–UAE renewable energy corridor[35] are accelerating the formation of a Mediterranean supergrid capable of balancing renewable flows across continents. Meanwhile, Italy’s energy network operator Snam secured EU backing in December 2025 for two flagship initiatives: the SoutH2 Corridor, a transcontinental hydrogen route connecting Algeria, Italy, Austria, and Germany, and the Callisto CO₂ Storage Project, which will establish offshore carbon storage capacity in the Adriatic.[36] Their inclusion in the EU’s Projects of Common Interest and Mutual Interest lists will accelerate financing and permitting—crucial steps in transforming Southern Europe into a central artery of Europe’s decarbonization strategy.

Alongside large-scale infrastructure, more agile industrial partnerships are emerging. In October 2025, the Italian Trade Agency (ITA) signed a memorandum of understanding with the World Future Energy Summit in Abu Dhabi to strengthen cooperation between Italian renewable technology firms and MENA clean energy projects.[37] This agreement points to a structural evolution: Southern Europe is no longer merely a consumer of MENA energy but a co-developer of technologies, value chains, and industrial capacity. These partnerships reflect the growing complementarity between European innovation ecosystems and Gulf capital, particularly in solar, green hydrogen, and grid modernization technologies.

Italy’s Mattei Plan for Africa reinforces this multidirectional strategy. By prioritizing energy transition, digital infrastructure, and scalable industrial development, the Plan aligns closely with the EU’s Global Gateway and with Gulf investment strategies in North Africa. The synergy between IMEC-related initiatives, African energy corridors, and Mediterranean interconnectivity is gradually turning Southern Europe into an operational interface between European policy goals, African production capacity, and Gulf financial and technological resources. Yet this architecture faces a major obstacle: a persistent “climate spending deadlock,” whereby Europe’s climate ambitions are not matched by the necessary public or private capital allocations. In this context, Gulf investors—particularly from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE—have emerged as pivotal partners capable of bridging Europe’s climate-financing gap and accelerating the deployment of new energy infrastructures.[38]

The broader geopolitical context remains complex. At the 2025 United Nations Climate Change Conference COP30 in Belém, leaders failed to agree on a roadmap to phase out fossil fuels, and global emissions are projected to peak at new record levels in 2025.[39] This outcome has sharpened the tension between climate ambition and geopolitical realism. For Europe—and for Southern Europe in particular—the challenge is to maintain credibility as a climate leader while navigating a world in which energy security, supply-chain resilience, and industrial competitiveness increasingly dictate policy choices.

Within this landscape, partnerships with MENA countries are becoming a pragmatic and technically grounded component of Europe’s green transition. The Mediterranean is evolving from a peripheral buffer zone into the core of an interdependent energy and industrial ecosystem spanning Europe, Africa, and the Gulf. If managed strategically, this emerging network could enable Europe to reconcile its ethical aspirations with the hard constraints of energy security—transforming Southern Europe into the pivotal hinge of the continent’s decarbonization efforts.

[1] Tiziano Marino and Alexandru Fordea, “Building IMEC: The Path towards the Implementation of the Indo-Mediterranean Corridor,” report, CeSI, September 2025, 4, https://www.cesi-italia.org/en/articles/building-imec-the-path-towards-the-implementation-of-the-indo-mediterranean-corridor.

[2] Emanuele Rossi, “Italy Eyes the Three Seas—With IMEC as Its Strategic Compass,” Decode39, December 2025, 3, https://decode39.com/12662/italy-eyes-the-three-seas-with-imec-as-its-strategic-compass/.

[3] Julien Barnes-Dacey and Cinzia Bianco, “Intersections of Influence: IMEC and Europe’s Role in a Multipolar Middle East,” commentary, European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), September 2023, 15, https://ecfr.eu/article/intersections-of-influence-imec-and-europes-role-in-a-multipolar-middle-east/.

[4] Giulia Giordano and Lorena Stella Martini, “Prospects for Peace in the Middle East via the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor,” commentary, ECCO Think Tank, April 2025, 4, https://eccoclimate.org/prospects-for-peace-in-the-middle-east-via-the-india-middle-east-europe-economic-corridor/.

[5] Francesco Maria Talò, “L’Italia deve guidare la crescita nell’era dell’incertezza globale,” Forbes Italia, October 28, 2025, https://forbes.it/2025/10/28/francesco-maria-talo-litalia-deve-guidare-la-crescita-nellera-dellincertezza-globale.

[6] Emanuele Rossi, “Italy’s Parliament Moves on IMEC (Bipartisan),” commentary, Decode39, November 25, 2025, https://decode39.com/12539/italys-parliament-moves-on-imec-bipartisan/.

[7] Marco Masciaga, “Tajani in India to Strengthen Economic, Cultural and Political Ties: Meetings with Modi and Jaishankar,” Il Sole 24 Ore, December 10, 2025, https://en.ilsole24ore.com/art/tajani-india-strengthen-economic-cultural-and-political-ties-meetings-modi-and-jaishankar-AIWM3BK.

[8] “Italia–India, Rixi e un Working Group per la Cooperazione Marittima e Logistica nel Corridoio IMEC,” AdnKronos, October 29, 2025, https://www.adnkronos.com/Archivio/economia/italia-india-rixi-e-il-un-working-group-per-la-cooperazione-marittima-e-logistica-nel-corridoio-imec_7BhcTXP9iJXVqWfzdPQZDN.

[9] Stefano Graziosi, “L’Italia nella Nuova Via India–Medio Oriente–Europa: Roma Cerca il Ruolo da Protagonista,” Panorama, November 27, 2025, https://www.panorama.it/attualita/politica/litalia-nella-nuova-via-economica-india-medio-oriente-europa-roma-cerca-il-ruolo-da-protagonista.

[10] Jaidaa Taha, “Qatar’s Ooredoo Plans $500 Million Investment in Cable Projects,” Reuters/Zawya, November 26, 2025, https://www.zawya.com/en/business/technology-and-telecom/qatars-ooredoo-plans-500mln-investment-on-cable-projects-lfd4ht4r.

[11] Barnes-Dacey and Bianco, “Intersections of Influence,” ECFR, September 2023.

[12] Emanuele Rossi, “India–EU: FTA Enters the Decisive Phase,” commentary, Decode39, December 2, 2025, https://decode39.com/12629/india-eu-fta-enters-the-decisive-phase/.

[13] Rosaleen Carroll, “Meloni to Attend GCC Summit in Bahrain as Italy Deepens Gulf Ties,” commentary, Al-Monitor, December 2, 2025, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2025/12/meloni-attend-gcc-summit-bahrain-italy-deepens-gulf-ties.

[14] “Meloni Confirms New Aid to Kyiv and Proposes a Gulf–Mediterranean Cooperation Council in Rome,” Agenzia Nova, December 3, 2025, https://www.agenzianova.com/en/news/meloni-italia-pronta-a-ospitare-un-vertice-consiglio-di-cooperazione-del-golfo-mediterraneo/.

[15] “Meloni Doubles Down on Italy–Gulf Strategy: Personal Diplomacy, Industrial Deals and a New Regional Architecture,” Decode39, December 3, 2025, https://decode39.com/12665/meloni-doubles-down-on-italy-gulf-strategy-personal-diplomacy-industrial-deals-and-a-new-regional-architecture/.

[16] Zain Hussain and Alaa Tartir, “Recent Trends in International Arms Transfers in the Middle East and North Africa,” commentary, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), April 2025, 10, https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2025/recent-trends-international-arms-transfers-middle-east-and-north-africa.

[17] Albert Vidal Ribé, “From Suppliers to Partners: Europe’s Growing Role in Gulf Security,” commentary, International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), October 28, 2025, https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/military-balance/2025/10/from-suppliers-to-partners-europes-growing-role-in-gulf-security/.

[18] Abdulhadi Habtor, “Italy Says It Is Ready to Deepen Defense Cooperation with Saudi Arabia,” interview, Asharq Al-Awsat, November 23, 2025, https://english.aawsat.com/gulf/5211832-italy-says-it-ready-deepen-defense-cooperation-saudi-arabia.

[19] Bilal Khan, “Qatar Inks $5.9 Billion U.S. Naval Warship Deal with Italy’s Fincantieri,” Quwa, August 2017, https://quwa.org/daily-news/qatar-inks-5-9-billion-u-s-naval-warship-deal-italys-fincantieri/.

[20] “EDGE Group and Leonardo Announce Key Milestone toward Landmark Joint Venture in the UAE,” press release, EDGE Group, November 19, 2025, https://www.etimad.ae/news/edge-group-and-leonardo-announce-key-milestone-toward-landmark-joint-venture-uae.

[21] “Fincantieri e ASRY Siglano un Accordo di Cooperazione Industriale in Bahrein,” press release, Fincantieri, December 3, 2025, https://www.fincantieri.com/it/media/comunicati-stampa-e-news/2025/fincantieri-e-asry-siglano-un-accordo-di-cooperazione-industriale-in-bahrein/.

[22] “Indra Group and EDGE Explore New Opportunities for PULSE NOVA in Electronic Warfare,” press release, Indra Group, November 17, 2025, https://www.indracompany.com/en/noticia/indra-group-edge-explore-new-opportunities-pulse-electronic-warefare.

[23] Ricardo Rubio, “Indra Creará una ‘Joint Venture’ en España para Fabricar Drones ‘Kamikaze’ con la Emiratí EDGE,” Europa Press, November 17, 2025, https://www.europapress.es/economia/noticia-indra-creara-joint-venture-espana-fabricar-drones-kamikaze-emirati-edge-20251117121345.html.

[24] Francesco Schiavi, “France’s Burgeoning Gulf Military Influence: Rafale Jets, Naval Systems and Integration,” commentary, Al-Monitor, February 15, 2025, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2025/02/frances-burgeoning-gulf-military-influence-rafale-jets-naval-systems-and.

[25] Francesco Schiavi, “Why France Is Quietly Becoming Saudi Arabia’s Go-To Internal Security Partner,” commentary, Al-Monitor, August 2025, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2025/07/why-france-quietly-becoming-saudi-arabias-go-internal-security-partner.

[26] Agnes Helou, “MBDA’s Planned Emirati Subsidiary Will Focus on Missiles and Loitering Munitions, Exec Says,” Breaking Defense, November 19, 2025, https://breakingdefense.com/2025/11/mbdas-planned-emirati-subsidiary-will-focus-on-missiles-loitering-munitions-exec/.

[27] Barın Kayaoglu, “Are Eurofighter Typhoons ‘Cost Prohibitive’ for Türkiye?” Türkiye Today, November 14, 2025, https://www.turkiyetoday.com/opinion/are-eurofighter-typhoons-cost-prohibitive-for-turkiye-3209907.

[28] Francesco Schiavi, “How Gulf States Are Powering Turkey’s Eurofighter Ambitions,” commentary, Al-Monitor, November 2, 2025, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2025/10/how-gulf-states-are-powering-turkeys-eurofighter-ambitions.

[29] European Commission, Directive (EU) 2024/1760 on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence, July 2024, https://commission.europa.eu/business-economy-euro/doing-business-eu/sustainability-due-diligence-responsible-business/corporate-sustainability-due-diligence_en.

[30] Bachar Halabi, “US, Qatar Warn EU Climate Rules Risk LNG Supplies,” Argus, October 22, 2025, https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news-and-insights/latest-market-news/2744835-us-qatar-warn-eu-climate-rules-risk-lng-supplies.

[31] Gulf Cooperation Council General Secretariat, “GCC States Warn of the Implications of the EU’s Proposed Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Legislation,” Riyadh, December 5, 2025, https://www.gcc-sg.org/en/MediaCenter/News/Pages/news2025-12-5-1.aspx.

[32] “Italy and Saudi Arabia Sign Energy Cooperation Agreement,” Reuters, January 14, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/italy-saudi-arabia-sign-energy-cooperation-agreement-2025-01-14/.

[33] Ajsa Habibic, “Eni Clinches Long-Term LNG Deal with QatarEnergy to Strengthen Italy’s Energy Security,” Offshore Energy, October 23, 2023, https://www.offshore-energy.biz/eni-clinches-long-term-lng-deal-with-qatarenergy-to-strengthen-italys-energy-security/.

[34] “New Italy–Greece Interconnection (GR.ITA 2),” Terna Driving Energy, accessed [add access date if required], https://www.terna.it/en/projects/public-engagement/italy-greece-grita-2.

[35] “Italy, Albania and the United Arab Emirates Sign €1 Billion Agreement for Adriatic Renewable Energy Link,” ESG News, January 17, 2025, https://esgnews.com/it/italy-albania-and-uae-sign-e1-billion-deal-for-adriatic-renewable-energy-link/.

[36] “Italy’s Snam Wins EU Backing for Hydrogen Pipeline and CO₂ Storage,” Reuters, December 1, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/italys-snam-wins-eu-backing-hydrogen-pipeline-co2-storage-2025-12-01/.

[37] “World Future Energy Summit Signs MoU with Italian Trade Agency to Increase Collaboration and Investment Opportunities,” World Future Energy Summit, 2025, https://www.worldfutureenergysummit.com/en-gb/news/wfes-signs-mou-with-italian-trade-agency.html.

[38] Lia Quartapelle, “Beyond the Mattei Plan: Italy’s Search for an Africa Policy,” commentary, European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), January 22, 2024, https://ecfr.eu/article/beyond-the-mattei-plan-italys-search-for-an-africa-policy/.

[39] Francesca Canto, “Accordo Debole alla COP30: Tanti (Ancora) i Nodi da Sciogliere,” TgCom24, November 23, 2025, https://www.tgcom24.mediaset.it/2025/video/accordo-debole-alla-cop30-tanti-ancora-i-nodi-da-sciogliere_106346463-02k.shtml.