1. Türkiye’s Energy Policy

Türkiye is a regional power located at the crossroads of important energy transit corridors, trade routes, and seaways. In a neighborhood characterized by deep-rooted rivalries, it is surrounded by failed states, autocracies, and civil wars, where political instability and prolonged conflicts are the norm. Having achieved domestic political and security consolidation over the last century, Türkiye is pursuing, first, protection from neighbors/external powers, and second, the expansion of its regional/global influence and the countering of potential challengers.

Although the country suffers from structural bottlenecks, weak institutions, and social cleavages that hinder foreign investment, it has ambitious plans for economic growth closely linked to access to energy resources. It is an OECD country and a NATO member in the league of G20, which places it in a unique position in the Middle East. To tackle unfolding geopolitical challenges on multiple fronts, Türkiye finds itself in a constant uphill struggle to adapt to emerging realities, redefine the rules of the game, and outpace its rivals in a rapidly evolving threat landscape, such as in Syria, Iraq, and the Caucasus.

In this context, the central question of this article is: “What factors have shaped Türkiye’s quest for energy security recently? Why has access to natural gas heightened in importance?”

During the AKP government’s term over the last 22 years, Türkiye’s foreign policy has shifted from focusing on EU membership (2003–2009) to political upheavals in the Middle East (2010–2016), then to rising nationalism (2016–2020), along with strategic balancing between the United States (U.S.)/European Union (EU) and Russia (2020–2024). In 2020, the COVID-19-induced economic recession quickly turned into a global fallout of unprecedented scale, laying bare the fragility of the U.S.-led post-World War II neoliberal world order and putting further strain on Türkiye’s brittle economy.

The Russia-Ukraine War that started in 2022 has heightened Türkiye’s geopolitical significance and increased its maneuverability and ability to engage in issue-based, transactional deal-making between multiple power centers. Compounded by Donald Trump’s second term in the U.S. White House, the new norm of this era is characterized by a multi-layered, multi-centered order of international relations involving many local actors with overlapping economic, social, and political interests, driving a longer-term shift toward greater self-sufficiency, economic nationalism, and strategic autonomy.

Facing these challenges, Türkiye embarked on an aggressive economic roadmap for 2027 to achieve a 5% GDP growth rate per annum, a 7% inflation rate, and a per capita income of US$20,420. [1] The country’s soft underbelly is economic fragility, with energy accounting for 20% of Türkiye’s total imports—a significant liability given its chronic current account deficit, which was US$45 billion in 2023.[2] To support the economic program and minimize exposure to external shocks in energy prices, the government pledged to achieve carbon neutrality by 2053 and took initiatives to adopt clean energy by transitioning from fossil fuel combustion to environmentally friendly policies and green investments.

In this context, energy security for Türkiye means access to affordable, sustainable, and reliable resources to maintain its annual economic growth targets. Especially after Russia’s annexation of parts of Ukraine, first in 2014 and then in 2022, and the monopolization of land routes for energy supply to Europe, Türkiye has attempted to diversify its energy sources and reduce import dependency. Part of this policy shift is evident in Türkiye’s assertiveness and intervention in the near abroad, as well as its quest to tap into offshore energy fields for potential windfall profits from natural gas exploitation.

Although Türkiye has invested as a priority in local fields that are accessible, non-disputed, and feasible, such as renewable energy, nuclear power, and coal mines, it still depends on natural gas consumption for the foreseeable future to sustain its economy. However, as Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Russian President Vladimir Putin take their close relationship to new heights, the war in Ukraine carries the risk of making Türkiye once again excessively dependent on Russia for energy—coal, natural gas, and nuclear.

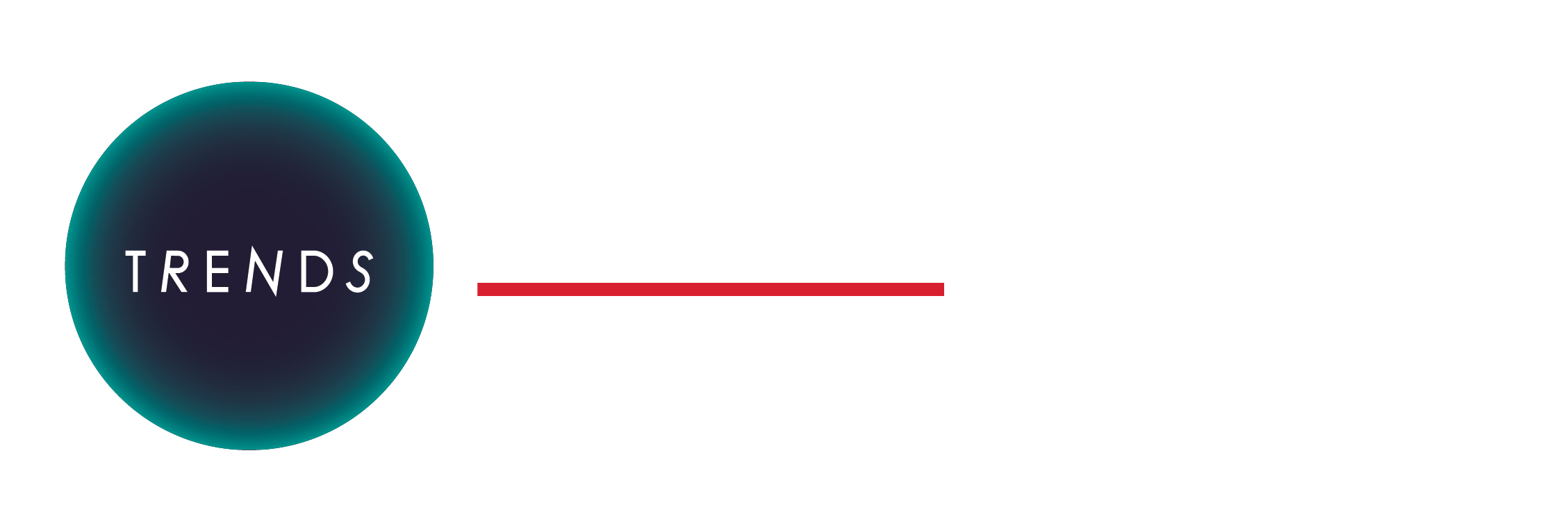

Figure 1: Share of Fossil Fuels in Türkiye’s Energy Consumption

Source: Enerdata, https://eneroutlook.enerdata.net/turkey-energy-forecast.html.

While on the supply side Türkiye looks at the Black Sea as a key step toward energy independence and considers creating a gas hub in Eastern Thrace with Russia, it also tries to improve demand-side factors by increasing energy efficiency. Keeping in sight the fact that global energy markets are in flux, Türkiye should further diversify sources of natural gas inflows and bring together multiple sources, including the Black Sea, Eastern Mediterranean, Azerbaijan, possibly Turkmenistan, and Northern Iraq; optimize its energy mix on better commercial terms; and reduce wasteful energy consumption from 35% to 10%. Removing subsidies for consumers of more than 5,000 KWh (kilowatt-hours) per year of electricity, about 3% of subscribers, is a positive step in that direction.[3] This would not only support energy transition but also reduce geopolitical risks by avoiding overreliance on a few dominant suppliers and enable a more sustainable energy ecosystem in the long term.

2. The Challenge: Availability of Affordable, Sustainable, and Reliable Natural Gas

Türkiye meets 75% of its total energy demand through imports; in its energy mix, natural gas has a roughly 26% share, almost on an equal level with oil and coal,[4] with Russia as the primary source in all three categories. Gas is an important commodity not just for the economy but also as a transition fuel to tackle long-term climate change. Türkiye currently has 7 gas pipelines, 5 LNG terminals, 3 floating storage units (FSRUs), and 2 underground storage facilities.

Although Türkiye’s footprint in global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is just over 1%, the negative effects of global warming and climate change on its land and nature are conspicuous and intense. To address these pressing issues, the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources formulates energy policy and oversees resource management, although ultimate decision-making power rests with the presidential office, which sets the agenda in line with the priorities of the treasury, foreign, and defense ministries.

The Ministry of Energy drives the agenda and executes long-term plans to expand available resources for the country, which, in theory, should align with the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change, but in practice, they might diverge substantially. For instance, to accelerate mitigation of GHG emissions and adopt an inclusive, resilient, and sustainable growth strategy, Türkiye ratified the Paris Climate Agreement (2015) in 2021 and committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2053.[5] There is also an emissions trading system to align Turkish carbon legislation with the European market, which started in several pilot cities with plans for full roll-out in 2026. These are important pledges for decarbonizing power generation and transport, the two most important pillars of climate mitigation.

In the Ministry of Energy’s plan, low-quality coal-powered plants still play an important part in the electricity supply network, meeting 36% of domestic demand. Türkiye has become Europe’s largest coal importer and coal-fired electricity producer, outpacing Germany and Poland, in parallel with its higher average GDP growth rate of 4.5%.[6] To elaborate on the impact, the spread of electric vehicles (EVs) in the Turkish market through Chinese investments such as BYD might reduce oil demand, but they contribute only a tiny amount to reducing emissions—and hence meeting 2053 targets—if their batteries are charged from a coal-heavy grid.

These contradictory objectives obscure the fact that Türkiye’s carbon footprint will peak in 2038 and only then start to decline, leaving a very short timeframe of just fifteen years to meet the stated target.[7] This roadmap has practical challenges, not to mention regulatory, strategic, and economic repercussions. At present, the country depends on imports to meet 98% of domestic natural gas consumption. It has also not pledged to close its currently active 67 coal-fired power plants, which account for 42% of total CO2 emissions from fossil fuels. On the contrary, it plans to expand them by a further 10% by 2035;[8] mainly because, according to Turkish Minister of Energy and Natural Resources Alparslan Bayraktar, “gas and electricity demand rose by three-fold in the past decade.”[9]

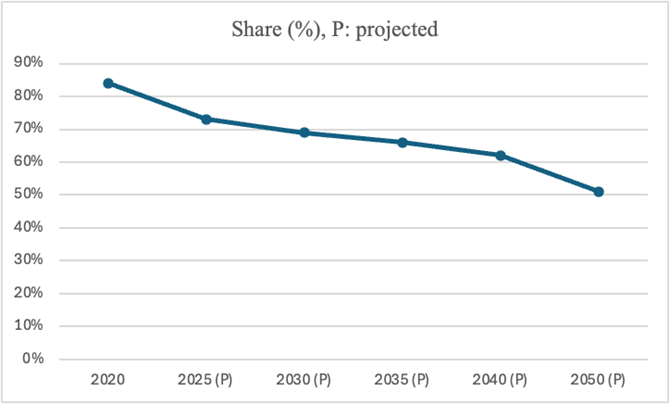

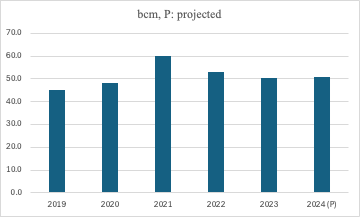

Figures indicate, however, that contrary to expectations, gas demand has decreased, if not remained largely unchanged, over the last three years. According to figures from the Energy Ministry, of Türkiye’s 80–85 bcm/year total import capacity, pipelines can supply 60–65 bcm/year and LNG 20–25 bcm/year. Both routes remain underutilized. By the end of 2021, out of the US$50.7 billion paid for energy imports, about US$30 billion was spent on 58.7 billion cubic meters (bcm) of imported gas. In 2022, overall demand for gas fell to 54 bcm due to high prices and the economic crisis in the country, although the total energy import bill jumped to US$80 billion.[10] Gas imports declined further in 2023 to 50.8 bcm due to a drop in domestic consumption.

Figure 2: Türkiye’s Natural Gas Consumption, 2019-2024

Source: The author, EPDK, https://www.epdk.gov.tr/Detay/Icerik/1-1275/natural-gasreports.

Imported gas is sourced from a variety of countries in the region and beyond.[11] Pipeline gas from Azerbaijan, Iran, and Russia still accounts for the largest portion of the imported volume, although their share decreased from a peak of 87% in 2013 to 71% in 2023.[12] Türkiye’s mid-to-long-term contracts provide 47.8 bcm/year, of which 27 bcm is sourced via pipelines from Russia.[13] Despite LNG imports nearly tripling in volume in recent years to 10 bcm, dependence on long-term, take-or-pay pipeline contracts with destination clauses, minimum purchase commitments, and oil-indexed high prices continues to create geopolitical risks for Türkiye.

With GDP growth projected to slow down to 2.6% in 2025 and 3.8% in 2026,[14] Türkiye will require a smaller share of pipeline gas for domestic consumption.

Normally, pipeline gas is more reliable and affordable than LNG, but geopolitical factors make it extremely risky to rely entirely on a single monopoly supplier with strict conditionalities. If pipeline gas falls short, spot-LNG imports often become the fallback option, inflating the already high gas import bill. In 2023, the share of spot-LNG in the gas mix reached 19.6% of total imports, half of which came from the U.S.[15]

Figure 3: Türkiye’s Oil and Gas Network

Source: BOTAŞ, https://www.botas.gov.tr/pages/natural-gas-and-crude-oil-pipeline-map/416.

Against this backdrop, perhaps the most positive aspect of Türkiye’s diversification strategy is the initial phase of Black Sea gas delivery from the Sakarya field to the pipeline network in April 2023. With estimated reserves of 710 bcm, worth roughly US$1 trillion at market prices,[16] the field is expected to meet 7% of domestic demand initially,[17] rising to 15%—or 7.5 bcm/year—by 2026 and up to 30%—or 15 bcm/year—during the plateau production period in 2027–2028. However, uncertainties remain about the accuracy and feasibility of these estimates.

The quickest way for Türkiye to reduce gas dependence would be to increase the share of renewables and nuclear in its energy mix, but there are challenges. According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) World Energy Outlook 2024 report, global natural gas consumption will plateau by the end of the decade, although hydrocarbons are still expected to meet 60% of global energy demand by 2050.[18] The war in Ukraine accelerated growth in renewables such as wind and solar,[19] but the intermittency of these resources requires backup systems to remain in place for the foreseeable future. Progress in Türkiye’s civilian nuclear program has been slow due to various roadblocks—technical, financial, and political—such as Germany’s ban on the sale of equipment to the Russian-built Akkuyu power plant.

Figure 4: Türkiye’s Natural Gas Imports, 2019-2024

Source: The author, EPDK, https://www.epdk.gov.tr/Detay/Icerik/1-1275/natural-gasreports.

The IEA had previously estimated that gas would fare better than other fossil fuels, projecting “a 30% rise in global demand by 2040,”[20] but this assumption is now outdated. Due to regulatory ambiguity and global underinvestment, gas markets will remain tight until at least 2025 and likely into the 2030s. Global long-term LNG contracts are sold out until 2026, and prices are expected to remain high.[21] However, global LNG export capacity is projected to grow by 50% in the next six years, driven primarily by the U.S. and Qatar, with up to 270 bcm anticipated to enter the markets by 2030.As a bridge solution, Türkiye has signed long-term LNG import contracts with ExxonMobil (U.S.), Shell (UK), TotalEnergies (France), and Sonatrach (Algeria) to help manage its gas bill and reduce reliance on pipeline imports. With increased storage capacity, FSRUs, and the flexibility to re-export, Türkiye’s LNG infrastructure has become the backbone of its diversification efforts. Consequently, the share of LNG in gas imports has doubled over the past decade.

In parallel, the share of renewables in Türkiye is rising—“it ranks fifth in Europe and twelfth in the world”[22]—and the Ministry of Energy has set a target to meet 30% of total energy demand from renewable resources by 2030. The plan is to increase the share of renewables in power generation to 47.8% by 2025 by boosting output from solar, wind, hydroelectric, and geothermal energy. The share of natural gas in electricity generation is expected to fall from 21.2% to 18.9%. However, these efforts alone are insufficient to ensure reliable and affordable energy supplies. More attention must be devoted to energy efficiency and climate mitigation. For instance, in solar energy, Türkiye is the “world’s fourth-largest solar panel producer”[23] and home to the largest solar farm in Europe. It has a gross solar energy potential of 116 GW (equivalent to 110 days of sunlight per year),[24] with an installed capacity of 16 GW and plans to increase this to 51 GW by 2035.[25] However, hot weather and droughts due to climate change reduce the utility of wind and hydropower in many regions, leading to under-capacity production. A 2022 study shows that seasonal output from onshore wind power plants in the country’s best wind corridor, on the Aegean coast, provides only 100 days of availability,[26] which requires per year, requiring support from baseload fuels such as natural gas and coal to sustain electricity generation. Similarly, hydropower’s share in the renewable mix dropped from 31% to 20% in 2023 due to droughts,[27] adding more impetus to fill the gap through increasing reliance on coal-fired power plants to fill the gap.

Although renewable energy constitutes more than half (67 GW) of Türkiye’s installed capacity (114 GW),[28] the total share of renewables in electricity generation remains modest at 42%.[29] In a business-as-usual scenario, according to Istanbul-Sabancı University’s International Center for Energy and Climate (IICEC), renewables will account for only 60% of installed power capacity by 2030.[30] The Ministry of Energy’s national energy plan, however, has a more ambitious target to quadruple renewable capacity from 30 GW to 120 GW—65% of the projected total of 190 GW—by 2035 through an investment of US$108 billion.[31]

Demand-side factors are also important contributors to the country’s energy roadmap and the place of gas in it. The bulk of imported gas is used in household consumption (32%), industrial production (27%), and electricity generation (21%).[32] Although the war in Ukraine dampened unabated gas consumption, induced gas-to-coal switching, and accelerated the adoption of renewables, more LNG production capacity coming online in the second half of this decade means gas supply shortages will be temporary. By contrast, the share of renewables in industry, residential, and transport sectors is much lower and remains prone to foreign exchange rate fluctuations and government incentives or subsidies.

Under the stated policies scenario, gas remains an ideal option during the energy transition for emerging countries of the Global South, such as Türkiye. Accordingly, it would not be wrong to infer that the ambitious mid-term economic plan laid out by the Turkish government prioritizes short-to-mid-term energy security and affordability over long-term emissions reduction and climate mitigation. Energy Minister Bayraktar confirmed during his speech at the St. Petersburg International Gas Forum that Ankara’s “gas import strategy has two main aims – supply security and affordability.”[33] This is a case of economic necessity, where reliability, sustainability, and affordability of energy risk becoming an “impossible trilemma” in which a country cannot achieve all three simultaneously.[34]

3. Regional Energy Geopolitics and Implications for Türkiye’s Gas Sector

Just as the world began recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine sent shock waves across energy markets within weeks, plunging them into turmoil. Europe was the hardest hit, with gas prices soaring twenty times above pre-war levels, reaching the equivalent of $650 per barrel of oil at their peak in summer 2022. In 2021, Europe imported 155 bcm of gas from Russia, meeting 40% of its total demand. Due to sanctions, energy conservation, and efficiency measures, gas demand in Europe fell by 25% in 2022 compared to the prior five-year average.[35] Since Europe has an energy-intensive industrial backbone, leading consumers such as Germany and France relied on coal, nuclear power, and renewables to replace the 50% drop in Russian pipeline supply, equivalent to almost 80 bcm/year. On the positive side, the next five years will see 2,400 GW of additional renewable capacity globally, equivalent to the rise over the past twenty years. This is promising for climate activists and technology providers supporting the European Green Deal, which aims to set the EU on the path to a green transition and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.However, this upside must be viewed in light of harsh geopolitical realities. As one-third of the world heads for a recession,[36] Europe faces the challenge of quickly re-aligning its energy security, industrial policy, and climate mitigation targets. Although Europe filled its gas storage facilities in 2022–23 due to reduced demand in China and India, when demand rebounded in 2024, it pulled most of the LNG, putting further strain on the market.

Global gas demand grew by 2.5% this year to a record high of 4,200 bcm, driven mostly by growth in the Asia-Pacific region.[37] The EU ministers agreed on a €180/MWh (megawatt-hour) natural gas price cap, but the deal failed to achieve its stated objective—inducing a policy change in Russia—let alone resolving persistent price challenges or the increased reliance on LNG.[38] This is compounded by Europe’s perennial struggle to balance sensitive issues such as national defense, security, and stronger unity with collective autonomy.

By comparison, the U.S. economy is in better form to weather the crisis amid weakening demand and a decline in global growth. Major financial institutions forecast the U.S. dollar to remain strong through 2025 as the U.S. Federal Reserve (FED) may slow down interest rate hikes to tame inflation in the wake of potential tax cuts, tariff increases, and fiscal spending. Washington has more maneuverability than Europe, as energy constitutes a smaller portion of its supply-side inflation.

Furthermore, the Trump administration may see an advantage in keeping the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which includes a green energy subsidy package to empower American local industry and accelerate energy transition. However, this has been a major issue of criticism in Europe on grounds of unfair competition and barriers to trade, prompting calls for a complaint to the World Trade Organization (WTO).[39] Brussels is not free of guilt either, as it has introduced its own strict European Carbon Border Tax initiative, which effectively acts as a tariff barrier toward third parties like Türkiye.[40]

Before the war in Ukraine, Russia sold 55% of its oil and 65% of its gas to Europe from West Siberia. Pipeline attacks on Nord Stream 1 and 2 rolled back the European-Russian energy integration project and, at least in theory, freed gas flows to go elsewhere. Yet, despite Moscow’s intention to quickly find substitutes, the IEA estimates it will take at least ten years to redirect gas to new customers.[41] The primary reason is that Russia’s gas fields are in geographically challenging locations and require sophisticated technology that is now unavailable due to Western sanctions on exports and the blacklisting of individuals on Russian executive boards.

Türkiye pursues its energy diplomacy within a broader strategy of bolstering its status as a regional power, leveraging its geographic position and connections.[42] In this context, Türkiye offered to pay for some Russian gas in rubles,[43] asked for a 25% discount on the contracted price, and requested to delay payments of about US$20 billion until 2024 to ease pressure on the lira (TL).

This move was not unjustified, as during an economic crisis, Türkiye’s state-owned pipeline operator, BOTAŞ, paid US$228 per 1,000 m³ of Russian gas, even when spot prices in Europe had fallen below US$100 per unit in 2020.[44] Conversely, Türkiye paid an exorbitant European hub-indexed price of US$340 at its peak in 2022 after a last-minute renewal of the contract with Russia just before the war in Ukraine.[45] However, the current supply glut in Russia, overcapacity, and discounted prices for Asian markets make prior contracts with rigid clauses seem obsolete.

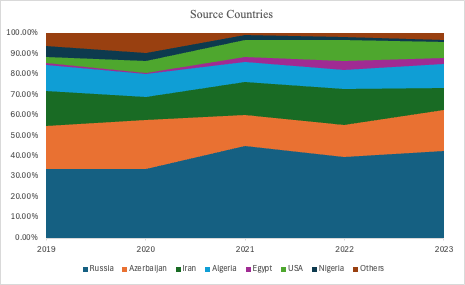

Figure 5: Türkiye’s Source of Natural Gas Imports, 2019-2023

Source: EPDK, https://www.epdk.gov.tr/Detay/Icerik/1-1275/natural-gasreports.

The strategic impact of dependence on inflexible pipeline contracts is most acutely felt in Türkiye’s bilateral relations with Russia and Iran, its first and fourth largest gas suppliers, respectively. The volume of Türkiye’s gas imports from Russia remained steady in 2023 at 21 bcm, but its share increased from 39.4% to 42.3%, while export contracts between Gazprom and BOTAŞ are set to expire in late 2025.[46] Iran and Türkiye have a 10 bcm/year gas import contract until 2026, although the two countries have reached a preliminary agreement to expand “gas transmission capacity, technical and engineering services.”[47]

Iran likely abandoned hopes of reviving the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), also known as the nuclear deal, and becoming a major gas supplier to Europe after President-elect Trump’s second-term victory. Türkiye’s plan to transport gas from Turkmenistan and the Iraqi Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) to Europe has further added to anxieties in Tehran, shelving its earlier aspirations of becoming a mega supplier. Such geopolitical factors and Türkiye’s efforts to extend control over conflict hotspots in the region—from Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq to Karabagh and Central Asia—have placed Türkiye in a delicate position with Iran and heightened the importance of energy corridors connecting producers in the East with demand centers in the West.

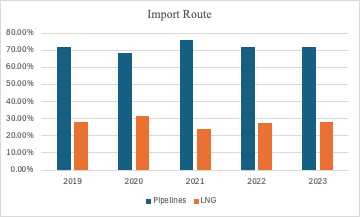

Figure 6: Türkiye’s Natural Gas Import Routes

Source: EPDK, https://www.epdk.gov.tr/Detay/Icerik/1-1275/natural-gasreports.

Before the war in Ukraine, the Turk-Stream and Blue-Stream routes, with a total capacity of 32 bcm/year to bring Russian gas to Türkiye’s largest cities, Ankara and Istanbul, gave Moscow latitude to dictate its terms through coercive tactics. Similarly, the Tabriz-Ankara gas pipeline provided economic leverage to Iran in regional gambits that Türkiye worked hard to counter.[48] In the aftermath of the war, the isolation of Russia and Iran by the West means Türkiye is no longer as asymmetrically exposed to pressure from these incumbent suppliers seeking to control gas flows.

The Black Sea Grain Initiative, under Türkiye’s mediation, established a humanitarian maritime corridor to and from Ukraine to allow the export of grain and fertilizers, alleviating global shortages of agricultural products.[49] When Turkish President Erdoğan convinced his Russian counterpart, President Putin, to extend the deal beyond the initial 120 days, it signaled an important shift in Ankara’s role as a broker and its leverage over the Kremlin. Although Russia withdrew from the deal on 17 July 2023, Türkiye remains Russia’s only significant gateway to the Western world and holds more influence over Moscow than before.

Ankara is cautious about picking a side in the Ukraine war, knowing that a political fallout with Russia could cause severe economic disruptions and security risks. Also, aware of Türkiye’s sensitivity toward U.S. plans to turn Western Thrace in Greece into a new LNG hub for Eastern Europe, Moscow has proposed establishing a reciprocal gas hub in Eastern Thrace, Türkiye, for selling LNG to Europe. Bulgaria and Hungary became the first European customers of Türkiye’s supply grid, receiving cargoes from various international producers and bypassing Russian pipelines.[50] The Trans-Anatolian Gas Pipeline (TANAP) and Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) serve as critical routes for exporting gas to Europe from different sources. At some point, Türkiye aims to create its own blend and establish itself as a price-maker, not a price-taker, in the regional gas market. However, time is not on its side, as gas demand in Europe is falling rapidly.

Figure 7: Türkiye’s Natural Gas Production

Source: EPDK, AA, https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/ekonomi/turkiyenin-dogal-gaz-uretimi-karadeniz-kesfiyle-bir-yilda-yuzde-113-artti/3251330

Since Türkiye’s desire to join the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF)[51] and export Cypriot and Israeli gas to Europe will not materialize in the foreseeable future, it is crucial to consider the Russian-led gas hub project in Thrace without further delay. Türkiye has the financial backbone for a gas trading market in Istanbul (EPİAŞ), but careful planning is necessary. A true energy hub requires investment in at least 100 bcm of storage—posing a geological challenge—as well as multiple suppliers, buyers, and robust price-setting mechanisms. Türkiye has significant excess import capacity that could be used for the trading hub, but finding a critical mass of suppliers and financiers remains essential.

The first Russian-built nuclear plant in Mersin-Akkuyu could free up more gas for industrial production instead of heating and electricity in Türkiye, or even for export, within the next five years. However, as Europe reduces its dependence on Russia, Türkiye’s value as a transit country for Russian gas is lower than it was before the war. Since Türkiye does not participate in Western sanctions on Russia, there is an opportunity to renegotiate pipeline gas contracts on competitive terms, offering flexibility in an increasingly buyer’s market.

When a pipeline is built, “the balance of power shifts from supplier to buyer,”[52] and Türkiye has growing influence to secure deep discounts instead of being locked into wasteful contracts signed 20–30 years ago under outdated supply security logic in illiquid market conditions. For example, in 2013, Türkiye sued Iran at an international court and secured a 13.3% reduction in gas prices, setting a precedent for renegotiating pipeline contracts with unfair terms.

It would be wiser for Türkiye to use its advantage in an oversupplied regional market to avoid long-term dependence on Russia and Iran—not just for gas and coal but also for nuclear energy. Azerbaijan, Türkiye’s second-largest gas supplier, plans to increase its export capacity to 32 bcm/year through upstream projects and infrastructure expansion by 2027, potentially providing additional gas volumes well before 2030.

Still, due to limited storage capacity, the strategic importance of gas for industrial output, and reciprocity in regional trade partnerships, Türkiye should not eliminate pipeline inputs altogether but focus on short-term contracts based on gas-indexed prices without minimum-volume commitments. Ankara should also continue to prioritize developing offshore gas reserves not only in the Black Sea but also in the Eastern Mediterranean and reducing wasteful energy consumption in the domestic market to balance supply and demand.

4. Policy Recommendations

COVID-19 and subsequent wars in Ukraine, Israel-Gaza, and the Red Sea tempered the pace of globalization. Countries have prioritized regionalization to access domestic energy sources and increase resilience. The main dynamic driving Türkiye’s energy transition in the near term is supply security and affordability rather than sustainability. The government’s goal is to keep energy prices down, reduce inflation, and promote economic growth over the next four years. For Türkiye, natural gas is a cleaner, more critical fuel compared to oil and coal, sitting at the core of its long-term strategy to liberalize the energy market, establish a trading hub, and enhance its geopolitical importance. Clean energy transition, aligned with climate goals and net-zero emissions, supports Türkiye’s gradual shift toward using a higher share of local and renewable resources in power generation, with gas serving as an ideal transition fuel.

Pipeline gas remains important for Türkiye as part of its trade partnerships in the region, but it should be renegotiated on better terms in 2025–26. The regional supply glut in pipeline gas requires a strategic realignment in Türkiye’s energy policy with a long-term vision. This should aim to mitigate over-reliance on pipeline imports by replacing rigid, long-term contracts with short-term, flexible contracts, particularly with LNG.

The government’s overarching goal in energy geopolitics should continue to be denying monopoly power to any single supplier and maintaining a diverse set of partnerships through a “balance of threat” strategy. In parallel, it should enhance market liberalization, increase private sector competitiveness, and improve energy efficiency to better manage supply-demand dynamics in the local market.

[1] “’Orta Vadeli Programlar,’ T.C. Cumhurbaşkanlığı Strateji ve Bütçe Başkanlığı – SBB (Medium Term Programs.” Republic of Türkiye Presidency Strategy and Budget Directorate), September 2024, https://www.sbb.gov.tr/orta-vadeli-programlar/.

[2] “The World Bank in Türkiye: Economics,” World Bank, 2024, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/turkey/overview.

[3] “Elektrikte yüksek tüketime sübvansiyon kaldırıldı,” (Subsidy for High Electricity Consumption Scrapped) BloombergHT, November 16, 2024, https://www.bloomberght.com/elektrik-tuketiminde-subvansiyon-karari-resmi-gazetede-3734751.

[4] “IEA: Türkiye – Countries & Regions,” International Energy Agency (IEA), 2024, https://www.iea.org/countries/turkiye/natural-gas.

[5] “Türkiye: NDC Status,” UNDP Climate Promise (UNDP, 2022), https://climatepromise.undp.org/what-we-do/where-we-work/turkiye.

[6] G Gavin Maguire, “Turkey Becomes Europe’s Largest Coal-Fired Electricity Producer,” Reuters, May 21, 2024, Energy, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/turkey-becomes-europes-largest-coal-fired-electricity-producer-maguire-2024-05-21/.

[7] Asya Robins, “COP 27: Türkiye’nin yeni iklim hedefini uzmanlar nasıl yorumluyor?” (COP 27: Experts Analyze Turkey’s New Climate Target) BBC News Türkçe, November 16, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/turkce/articles/ceq20288wglo.

[8] Franceso Siccardi, “Understanding the Energy Drivers of Turkey’s Foreign Policy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (blog), February 28, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/02/understanding-the-energy-drivers-of-turkeys-foreign-policy?lang=en.

[9] Alparslan Bayraktar, “Keynote Remarks: Deputy Minister of Energy and Natural Resources, Republic of Turkey” (Atlantic Council: 2022 Regional Clean Energy Outlook Conference, Istanbul, Turkey, October 11, 2022).

[10] Adam Samson, “Turkey to Make Inaugural Deliveries from Big Black Sea Gas Discovery,” Financial Times, April 17, 2023, Turkey, https://www.ft.com/content/959b6f1d-8aaf-472f-9f61-7fdca4b1685e; “Russia Faces Challenges Over Turkey Hub,” Energy Intelligence (blog), February 8, 2023, https://www.energyintel.com/00000186-30b2-dc7f-a9bf-78be64000000.

[11] “Turkey Natural Gas: Imports, 1975–2022 | CEIC Data,” CEIC Turkey: Natural Gas Imports, 2022, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/turkey/natural-gas-imports.

[12] “EPDK | Enerji Piyasası Düzenleme Kurumu,”(Energy Market Regulatory Authority) EPDK: Natural Gas Report (2023), 2024, 20, https://www.epdk.gov.tr/Detay/DownloadDocument?id=3v67noeSz8o=.

[13] “Türkiye’nin arz güvenliği, uzun vadeli gaz kontratları ve Karadeniz keşfiyle garantide,” (Türkiye’s Energy Security Ensured through Long-Term Gas Contracts and Black Sea Exploration) AA (blog), January 5, 2023, https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/ekonomi/turkiyenin-arz-guvenligi-uzun-vadeli-gaz-kontratlari-ve-karadeniz-kesfiyle-garantide/2780119.

[14] “The World Bank in Türkiye: Economics.”

[15]“Türkiye’nin arz güvenliği, uzun vadeli gaz kontratları ve Karadeniz keşfiyle garantide.” Op. cit.

[16] “Erdoğan, Karadeniz’de keşfedilen gaz rezervinin 710 milyar metreküpe ulaştığını açıkladı: ‘Piyasa değeri 1 trilyon dolar,’” (Erdogan Announces Black Sea Gas Reserves Reach 710 Billion Cubic Meters with a Market Value of $1 Trillion) BBC News Türkçe, December 26, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/turkce/articles/clkx07prld4o.

[17] Adam Samson, op. cit.

[18] “World Energy Outlook 2024 – Analysis,” IEA, October 16, 2024, https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024.

[19] Rachel Pannett, “Renewables to Overtake Coal as World’s Top Energy Source by 2025, IEA Says,” Washington Post, December 12, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/12/12/renewables-coal-energy-crisis-iea-2022/.

[20] “World Energy Outlook 2020 – Analysis,” IEA, October 2020, https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2020.

[21] Tsevetana Paraskova, “Global Long-Term LNG Contracts Are Sold Out Until 2026,” OilPrice.Com (blog), November 21, 2022, https://oilprice.com/Latest-Energy-News/World-News/Global-Long-Term-LNG-Contracts-Are-Sold-Out-Until-2026.html.

[22] “Türkiye Ranks among Top 11 Countries in World in Renewable Energy Capacity,” AA: Energy Terminal (blog), May 29, 2024, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/energy/solar/turkiye-ranks-among-top-11-countries-in-world-in-renewable-energy-capacity/41813.

[23] Alparslan Bayraktar, op. cit.

[24] “Türkiye Güneş Enerjisi Potansiyeli Haritası Bölge (Türkiye Solar Energy Potential Map by Province) İl Güneşlenme Süreleri | ** POWER ENERJİ **,” Enerji (blog), November 8, 2022, https://www.powerenerji.com/turkiye-gunes-enerjisi-potansiyel-haritasi-bolge-il-guneslenme-sureleri.html.

[25] Zeynep Beyza Kılıç, “Türkiye Ulusal Enerji Planı yayımlandı,” (Türkiye’s National Energy Plan Published) AA (blog), December 31, 2022, https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/ekonomi/turkiye-ulusal-enerji-plani-yayimlandi/2776895; “Installed Solar Capacity Exceeds 16,000 MW – Latest News,” Hürriyet Daily News, August 11, 2024, https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/installed-solar-capacity-exceeds-16-000-mw-199387.

[26] “24 TV: Gündem Dışı,” Gündem Dışı (Istanbul, Turkey: 24 TV, November 17, 2022), https://www.yirmidort.tv/gundem-programlari/gundem-disi-kahraman-poyrazoglu/#1.

[27] “HES’lerin üretimdeki payı bu yıl yüzde 15’e gerileyebilir – Nasıl Bir Ekonomi,” (The Share of Hydroelectric Power Plants in Production May Drop to 15% This Year) Ekonomim.com (blog), April 4, 2023, https://www.ekonomim.com/ekonomi/heslerin-uretimdeki-payi-bu-yil-yuzde-15e-gerileyebilir-haberi-689307; Bloomberght, “Türkiye’de elektrik üretiminde yenilenebilirin payı yüzde 42’ye ulaştı,” (Renewable Energy’s Share in Türkiye’s Electricity Production Reaches 42%) Bloomberght (blog), May 8, 2024, https://www.bloomberght.com/turkiye-de-elektrik-uretiminde-yenilenebilirin-payi-yuzde-42-ye-ulasti-2352347.

[28] Igor Todorović, “Turkey Plans 89 GW of New Solar, Wind Power by 2035,” Balkan Green Energy News, October 25, 2024, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/turkey-plans-89-gw-of-new-solar-wind-power-by-2035/.

[29] Daily Sabah with AA, “Türkiye Aims for 47.8% Renewable Share in Electricity Production in 2025,” Daily Sabah, October 20, 2024, Energy, https://www.dailysabah.com/business/energy/turkiye-aims-for-478-renewable-share-in-electricity-production-in-2025; “IEA: Türkiye – Countries & Regions.”

[30] Bora Şekip Güray, “Türkiye Renewable Energy Outlook,” Turkey Energy Outlook (Istanbul, Turkey: Sabanci University Istanbul International Center for Energy and Climate| IICEC, December 2022), https://iicec.sabanciuniv.edu/treo.

[31] Zeynep Beyza Kılıç, op. cit.

[32] “Turkish Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources,” 2022, https://enerji.gov.tr/info-bankenergynatural-gas.

[33] David O’Byrne, “Turkey Nearing ‘Critical’ Phase in Gas Supply Arrangements: Minister,” October 11, 2024, https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-gas/101124-turkey-nearing-critical-phase-in-gas-supply-arrangements-minister.

[34] Christina Majaski and Michael J Boyle, “What Is a Trilemma and How Is It Used in Economics? With Example,” Investopedia, November 21, 2020, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/trilemma.asp.

[35] Shotaro Tani, “Europe Cuts Gas Demand by a Quarter to Shed Reliance on Russia,” Financial Times, December 5, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/0ab21afc-d034-4279-8ce1-4469d0ce8489?emailId=f83ce56c-b582-4f9f-9bd3-1789fa135baf&segmentId=22011ee7-896a-8c4c-22a0-7603348b7f22.

[36] “Third of World in Recession This Year, IMF Head Warns,” BBC News, January 2, 2023, Business, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-64142662.

[37] Stuart Elliott, “Global Gas Balance Still ‘fragile’ on Limited LNG Output Growth: IEA,” S&P Global, October 3, 2024, https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-gas/100324-global-gas-balance-still-fragile-on-limited-lng-output-growth-iea.

[38] Corrado Botta, “Is the EU Natural Gas Price Cap Effective? | IEP@BU,” Institute for European Policy Making, Bocconi University, 2024, https://iep.unibocconi.eu/publications/eu-natural-gas-price-cap-effective.

[39] Leigh Thomas, “Explainer: Why the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act Has Europe up in Arms,” Reuters, December 5, 2022, Markets, https://www.reuters.com/markets/why-us-inflation-reduction-act-has-europe-up-arms-2022-12-05/.

[40] Jan-Willem van de Ven, “Turkey and Europe’s Planned Carbon Border Tax,” European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), April 21, 2021, https://www.ebrd.com/news/2021/turkey-and-europes-planned-carbon-border-tax-.html.

[41] Fatih Birol, “World Energy Crisis and Renewable Energy Outlook | IICEC Sabancı University Istanbul International Center for Energy and Climate” (World Energy Crisis and Renewable Energy Outlook, Istanbul, Turkey, December 23, 2022).

[42]Siccardi, “Understanding the Energy Drivers of Turkey’s Foreign Policy.”

[43] Patricia Cohen, “Turkey Is Strengthening Its Energy Ties With Russia,” The New York Times, December 9, 2022, Business, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/09/business/turkey-erdogan-energy-russia.html.

[44] Therese Robinson, “Russia’s Plans for Natural Gas Hub in Turkey Facing Obstacles,” Natural Gas Intelligence (blog), December 21, 2022, https://www.naturalgasintel.com/russias-plans-for-natural-gas-hub-in-turkey-facing-obstacles/.

[45] “Gazprom Losing Once-Promising Turkish Market, Report Says,” Daily Sabah, September 4, 2020, https://www.dailysabah.com/business/energy/gazprom-losing-once-promising-turkish-market-report-says.

[46] “Russia’s Gazprom Export Signs New 4-Year Gas Supply Deal with Turkey’s BOTAŞ,” Caspian News, January 10, 2022, https://caspiannews.com/news-detail/russias-gazprom-export-signs-new-4-year-gas-supply-deal-with-turkeys-botas-2022-1-9-0/; Adam Michalski, “Turkey: Opportunities and Challenges on the Domestic Gas Market in 2024,” OSW Centre for Eastern Studies, June 3, 2024, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2024-06-03/turkey-opportunities-and-challenges-domestic-gas-market-2024.

[47] Newsroom, “Iran, Turkey Reach New Agreements over Gas Exports,” Modern Diplomacy (blog), October 24, 2022, https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2022/10/24/iran-turkey-reach-new-agreements-over-gas-exports/.

[48]Ebrahim Fallahi, “Iran’s Share in Turkey’s Future Gas Market,” Tehran Times, September 28, 2020, https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/452972/Iran-s-share-in-Turkey-s-future-gas-market.

[49] United Nations, “Black Sea Grain Initiative | Background,” United Nations: Joint Coordination Centre for the Black Sea Grain Initiative (United Nations, 2022), https://www.un.org/en/black-sea-grain-initiative/background.

[50] “Bulgaria Signs Deal for Gas Supplies via Turkey – DW – 01/03/2023,” Dw.Com (blog), January 3, 2023, https://www.dw.com/en/bulgaria-to-replace-russia-gas-supplies-with-turkeys-lng-terminal/a-64276016.

[51] Dina Ezzat, “Egypt-Turkey: Creative Detente – Egypt – Al-Ahram Weekly,” Ahram Online, December 1, 2022, https://english.ahram.org.eg/News/480771.aspx.

[52] Stefan Andreasson, “Stefan Andreasson on Twitter, Reader on Comparative Politics,” Twitter, September 21, 2020, https://twitter.com/StAndreasson/status/1308015056404316162.