The Aegean Sea, a body of water that lies between the eastern coast of Greece and the western coast of Türkiye, has long been a region of rich historical, cultural, and ecological significance. However, it has also been a focal point of territorial disputes and geopolitical tensions between the two nations. Amidst these ongoing disputes, there lies a compelling opportunity for cooperation that could not only mitigate tensions but also promote environmental conservation and sustainable development: the establishment of a joint sea park. This initiative would not only serve as a symbol of peace and cooperation but also as a crucial step toward preserving the biodiversity and natural beauty of the Aegean Sea.

A joint sea park in the Aegean Sea could redefine the nature of interactions between Türkiye and Greece, transforming a history of rivalry into a future of collaboration. It can be proposed that through joint environmental endeavors, both countries can forge a new path that benefits their people, the environment, and the broader region. Such cooperation can be called environment diplomacy or water diplomacy and could also pave the way for enhanced economic opportunities in areas such as tourism, fishing, and research, providing a mutual benefit that is too substantial to overlook.

Historical Context

The historical context of Türkiye-Greece relations concerning the Aegean Sea is complex and deeply intertwined with issues of national sovereignty, territorial rights, and cultural identity. These relations have been characterized by a series of disputes over sea boundaries, airspace, and the rights to drill for resources in the Aegean Sea.

The Aegean dispute essentially involves a series of interrelated conflicts between Türkiye and Greece over sovereignty and related rights in the Aegean Sea. This conflict has its roots in the early 20th century, with significant developments occurring after the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which set the boundaries of modern Türkiye. The treaty left several issues unresolved, particularly regarding the Aegean islands, many of which were placed very close to the Turkish coast but remained under Greek sovereignty.

During the 1970s, the discovery of potential undersea oil and gas deposits further complicated the disputes. Türkiye and Greece have differing views on how the continental shelf should be delimited and each conducted seismic surveys in the area to assert their claims. The Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which Greece supports and Türkiye has not signed, complicates the matter by allowing countries to claim extensive maritime zones, including territorial waters and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), which extend the sovereign rights of coastal states beyond their mere mainlands.

Another point of contention has been the military presence on the islands. Treaties such as the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne and the 1947 Treaty of Paris, which ceded the Dodecanese islands from Italy to Greece, restrict military fortifications and troops on these islands. However, Greece has militarized some of these islands, citing Türkiye’s significant military presence on its western coast, leading to Türkiye’s objections based on the terms of the treaties. The airspace over the Aegean Sea also remains a contentious issue, with frequent intercepts and dogfights occurring between Turkish and Greek military aircraft. Türkiye disputes Greece’s ten-mile air space, which does not coincide with the 6-mile-wide maritime boundary of territorial waters, asserting a right to freely use the airspace over what it considers to be international waters. There are also what are termed “gray zones” of islands/islets/rocks whose sovereignty is disputed and each side claims its own. Greece’s position is that the only negotiable issue with Türkiye is the extent of continental shelves/EEZs, not the status of islands, limits of territorial waters, or airspace rights.

Overall, the historical and ongoing disputes over the Aegean Sea between Türkiye and Greece are emblematic of the broader complexities and sensitivities in their bilateral relations. These disputes not only involve tangible issues like territory and natural resources but are also symbolic of national pride and sovereignty, which makes resolution challenging yet crucial for regional stability and cooperation.

How to transform the conflict zone into a field of cooperation

However, there are ways to transform this conflict zone into a cooperation field as both Greece and Türkiye owe their considerable amount of national revenues based on Aegean waters through tourism. This potential transformation has its legal base relying on the Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution, known as the Barcelona Convention, which aims to protect the Mediterranean by preventing and reducing pollution caused by ships, aircraft, and land vehicles in the Mediterranean within the scope of the “Regional Seas Program” established by the United Nations Environment Program in 1974.

The Barcelona Agreement, adopted at the Euro-Mediterranean Conference in 1995 on a larger scale, provides a framework for regional cooperation among Mediterranean countries, including Türkiye and Greece. The agreement established the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (Euromed), which aims to enhance economic and political stability through strengthened regional cooperation and dialogue.

Regarding the ongoing disputes between Türkiye and Greece in the Aegean Sea, the principles of the Barcelona Agreement could be instrumental in transforming these into cooperative efforts. The agreement emphasizes mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty, non-interference in the internal affairs of other states, and peaceful settlement of disputes—all fundamental principles that can guide the resolution of conflicts in the Aegean Sea. The agreement encourages continuous dialogue and diplomacy, which can be applied to ongoing negotiations over territorial and maritime disputes in the Aegean Sea. Setting up regular diplomatic meetings under the Euromed framework could help both sides articulate their concerns and expectations more clearly and constructively.

Also, one of the key components of the Barcelona Agreement is economic integration. By focusing on joint economic opportunities, such as tourism, fisheries, and energy exploration in the Aegean Sea, Türkiye and Greece could create a shared interest that helps mitigate broader geopolitical tensions. Developing joint projects that benefit both countries economically might encourage a more collaborative approach to disputed issues. Environmental protection is another significant aspect of the Barcelona Agreement. Türkiye and Greece could collaborate on marine conservation projects, such as establishing a transboundary marine protected area in the Aegean Sea, which could serve as a neutral ground for cooperation and help protect biodiversity and sustainable exploitation of marine resources. The agreement also lays a foundation for cooperation in enhancing security and stability in the Mediterranean region. Türkiye and Greece can work together under this framework to address non-traditional security threats such as illegal fishing, human trafficking, and smuggling, which are prevalent issues in maritime regions.

By recommitting to the Barcelona Agreement’s principles and objectives, Türkiye and Greece can utilize this existing framework to transform their disputes into collaborative initiatives. This would not only enhance bilateral relations but also contribute to the broader goals of peace, stability, and cooperation in the Mediterranean region. Such efforts would demonstrate how diplomatic frameworks can be effectively utilized to address and resolve longstanding regional disputes through constructive engagement and mutual interest.

From Barcelona Agreement to Athens Declaration

Building on the spirit of cooperation exemplified by the Barcelona Agreement, the proposed joint initiative in the Aegean Sea also aligns with the principles of the Athens Declaration, which was signed by Turkish and Greek leaders in Athens in December 2023 and marked a significant commitment to enhancing cooperation and resolving longstanding issues amicably. The declaration emphasizes the importance of dialogue, mutual respect, and peaceful resolution of disputes, underscoring the commitment of both nations to enhance their bilateral relations. By channeling the collaborative ethos of the Athens Declaration, the effort to establish joint economic, environmental, and cultural projects in the Aegean Sea not only reflects the specific agreements made but also embodies a broader commitment to regional stability and cooperation. This declaration could serve as a cornerstone for initiatives like the joint development of a sea park in the Aegean Sea.

Yet, the positive rapprochement between the two countries is shadowed by the Greek side’s step claiming to unilaterally declare a sea park in conflicted waters without due consultation with Türkiye. The Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that it will declare two new marine parks, one in the Aegean Sea and the other in the Ionian Sea, during the “Our Ocean” conference held in Athens on 16-17 April 2024. This initiative received a negative reaction from the Turkish Foreign Ministry. Denouncing exploitation of environmental issues for sovereign gains, Türkiye recommended Greece “not to involve the outstanding Aegean issues, and the issues regarding the status of some islands, islets and rocks whose sovereignty has not been ceded to Greece by the international treaties, within the frame of its own agenda.” [1] Greece nonetheless affirmed its intent to go ahead with the marine park project despite Türkiye’s objection.

Which marine zones in the Aegean Sea should be protected primarily?

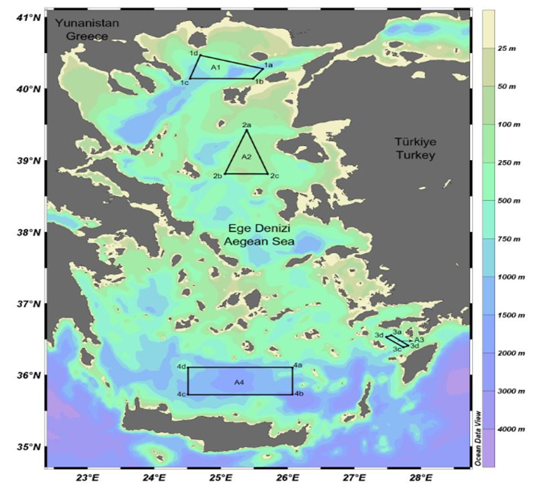

Right at this point, the Turkish Marine Research Foundation (TUDAV) which has been working on water and environment issues for twenty-seven years released maps of specific zones that should be protected in the Aegean Sea. According to Prof. Bayram Öztürk, the founder and president of TUDAV, the sea parks that Greece expressed its intention to declare within the scope of Natura 2000 are not so significant for marine species according to the outcomes of a scientific study. Prof. Öztürk proposes that, as shown in the map below, the zone in the Northern Aegean between Thassos, Gökçeada and Lemnos islands (a critical zone for fishing and marine life), the area to the west of Lesbos in the Central Aegean (coralliferous areas), the zone from Datça peninsula to Symi island, and the zone to the north of Crete are much more critical to protect biodiversity.

Map 1: Proposed marine protected areas in the Aegean Sea

Source: Turkish Marine Research Foundation[2]

TUDAV scientists state that cooperation is needed to protect these four conservation or marine park areas proposed in the Aegean Sea, emphasizing that the Aegean’s biodiversity has been under threat recently due to factors such as pollution, overfishing, alien species, and climate change. Nonetheless, it is not easy to resolve decades-long political disputes by simply announcing cooperation for water and the environment. Then, how can this policy recommendation by bioscientists be implemented?

How and why should Türkiye and Greece cooperate in the Aegean Sea?

First, it is crucial to establish a bilateral agreement that clearly outlines the governance and management of the joint sea park, ensuring that both nations have equal say and benefits. Such an agreement could be modeled on the principles of the Athens Declaration and further detailed within frameworks like the Barcelona Agreement, promoting dialogue and cooperation.

Secondly, involving international mediators or organizations might help provide a neutral perspective and facilitate trust-building measures. These entities can oversee the scientific and environmental assessments necessary to designate areas for conservation, ensuring that decisions are based on ecological importance rather than political considerations. A good mediator can be the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which introduced Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) number 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17 referring to life below water; climate action; life on land; peace, justice and strong institutions and partnerships for the goals. SDG 13 says that by preserving critical marine habitats, the sea park would contribute to climate regulation. Marine ecosystems like seagrasses, salt marshes, and mangroves are known to sequester carbon dioxide, thus playing a role in combating climate change. Joint management of these ecosystems can enhance resilience to climate-related impacts and natural disasters, which is a central aim of SDG 13.

The primary objective of the joint sea park aligns directly with SDG 14, which is to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources. The establishment of a marine protected area would help in preserving biodiversity, reducing pollution, and promoting sustainable fishing practices, thereby protecting marine life and ecosystems. While primarily focused on aquatic environments, the conservation efforts in the sea park also relate to SDG 15, which emphasizes the sustainable management of biodiversity and terrestrial ecosystems. Protecting the marine environment ensures the health of coastal areas that support terrestrial biodiversity and local communities. The initiative can promote peaceful co-existence through shared management and dispute resolution strategies, in line with SDG 16. This goal advocates for responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making at all levels.

By working together on this environmental project, Türkiye and Greece can foster a stable and peaceful relationship, establishing mechanisms for dialogue and cooperation that enhance governance and potentially reduce conflicts. SDG 17 can be referred to as the collaboration between Türkiye and Greece to establish a sea park and serve as an exemplar of international cooperation. This partnership could pave the way for further collaborative efforts in the region, leveraging resources, knowledge, and technologies for sustainable development. The proposed joint sea park in the Aegean Sea embodies the spirit of the SDGs by fostering an integrated approach to environmental conservation and sustainable development. It not only addresses specific ecological and climate objectives but also promotes peace and partnership between Türkiye and Greece, showcasing how collaborative environmental initiatives can serve broader socio-economic and political purposes.

Thirdly, initiating smaller, less contentious projects within the proposed joint sea park could demonstrate the benefits of cooperation and help build confidence between the two sides. Projects focusing on scientific research, joint monitoring of marine health, and combating pollution and overfishing can serve as foundational steps towards more significant cooperation. For Greece, the Aegean islands are a cornerstone of its tourism sector. Islands like Santorini, Mykonos, and Rhodes are global icons, drawing visitors from around the world who contribute to the local and national economy through expenditures on accommodation, food, entertainment, and transportation. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, tourism contributes approximately 20% to Greece’s GDP, with a substantial portion of this income generated from the Aegean islands. The region’s appeal not only boosts direct revenues from tourism but also creates thousands of jobs, supporting ancillary services such as local crafts, boat services, and the hospitality industry.

And the same goes for Türkiye. Similarly, the Aegean coast of Türkiye is vital to its tourism industry, featuring prominent destinations such as Marmaris, Bodrum, and Çeşme. These areas are famed for their beaches, historical sites, and resorts, making them popular with both domestic and international tourists. Türkiye’s tourism sector, significantly powered by its Aegean destinations, contributes around 11% to GDP. The unique cultural offerings, combined with extensive coastal activities, ensure a continuous influx of tourists, which not only bolsters the economy but also enhances the cultural exchange between the visitors and the locals. Globally, Greece and Türkiye rank among the top 15 destinations for sea tourism. The Aegean Sea is not just a body of water separating two nations; it is a bridge that connects them through the bustling activity of sea tourism. This mutual resource, if managed cooperatively, could further enhance the economic, social, and environmental well-being of both Greece and Türkiye, proving that their shared heritage in the Aegean Sea can bring about mutual benefits beyond the competitive spirit, fostering a relationship built on collaboration and shared prosperity.

A proposed roadmap

Describing the Aegean Sea’s magnitude of contribution to the national revenues of both Türkiye and Greece, Prof. Öztürk said: “They are selling clean waters, blue waters. If they do not protect the sea, after decades they will not have clean blue waters to sell.” By prioritizing transparency, mutual respect, and shared ecological and economic interests, Türkiye and Greece can overcome the existing barriers. The idea of a joint sea park not only has the potential to safeguard the rich biodiversity of the Aegean Sea but also to act as a beacon of peace and cooperation in a region that has seen too much discord. This endeavor, if successfully realized, could become a seminal model of how environmental diplomacy can bridge even the most turbulent waters. The joint sea park protection initiative of France, Italy and Monaco in the Mediterranean, which is also an exemplary model of transnational cooperation aimed at conserving marine biodiversity and promoting sustainable use of marine resources with a collaborative effort focusing on the establishment and management of a marine protected area (MPA) that spans portions of the waters of all three countries, sets a successful precedent. Why not, then, Türkiye and Greece?

[1] Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “No: 58, Regarding the Marine Park to be Announced by Greece in the Aegean Sea,” April 9, 2024, https://www.mfa.gov.tr/no_-58_-yunanistan-in-ege-denizi-nde-ilan-edecegini-duyurdugu-deniz-parki-hk.en.mfa.

[2] “TUDAV’s recommendations for offshore protected areas in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean,” TUDAV, https://tudav.org/calismalar/deniz-alanlari/ege-denizi/tudavin-ege-ve-dogu-akdenizde-acik-deniz-koruma-alanlari-onerileri/.