Viewers of China’s recent military parade watched an array of the latest AI-powered vehicles, laser weapons, and missiles roll through Beijing in an arresting display of technological and military confidence. At the reviewing stand were Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, and Kim Jong Un, a trio widely seen as posing the most obvious challenge to the Western-created and progressively unraveling “global order”. For many, the spectacle seemed to confirm an increasingly global narrative: the East is rising, and the West is falling (东升西降). The less remarked upon, yet equally notable, attendance of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and several of the “middle power countries” at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit in Tianjin in the same week further underscores the shifting dynamics at play.

Yet the reality is far more nuanced. The story of the 21st century is not a simple narrative of “decline” and “rise,” it is rather a complex rebalancing. It is premature to assert that this is a Cold War-style ideological showdown or a linear transfer of geopolitical power. The once-tidy “democracy vs. authoritarianism” dichotomy no longer holds in the era of U.S. President Donald Trump, as domestic polarization and a more transactional approach to alliances blur ideological lines. We are witnessing a messy, uneven rebalancing, where the “rise” of the East is not primarily synonymous with China’s ascent, and the “decline” of the West is partially self-inflicted. To understand this complexity, we must grasp five critical truths about what “East Rising, West Falling” really means—and what it doesn’t.

The West’s Decline Narrative: A Bipartisan Consensus, but Built on Half-Truths

In Washington, declinism has noticeably become a rare bipartisan language. On the right, President Trump’s MAGA project is premised on “American carnage”, a story of a country hollowed out by unfair trade agreements, taken advantage of by allies, and bled by endless wars. In this worldview, the roots of decline are largely domestic: porous borders, deindustrialization and offshoring, a complacent “globalist” elite, and cultural institutions seen as captured by “woke” orthodoxy, rather than the inevitable by-product of global change. In May, Vice-President JD Vance stated bluntly that “The era of uncontested U.S. dominance is over”, casting America as overextended and misled by elites, with a diminished industrial base and unsustainable global commitments that demand a sharp recalibration.[1]

On the left, Democrats warn that if the United States pulls back from the liberal order, a power vacuum will be filled by assertive autocracies. They argue that President Trump’s challenges to democratic norms at home, alongside his willingness to upend long-standing alliances, are eroding U.S. democratic resilience and diminishing American soft power and credibility abroad. Following the election of President Trump to his second term, both sides of the aisle increasingly reinforce a narrative of Western decline as fait accompli.

While the rhetoric is American, the empirical referent extends to Europe. In terms of the war in Ukraine, Europe has been unable to generate military effects commensurate with its stated aims, hobbled by depleted stockpiles, fragmented procurement, and a slow industrial ramp-up.[2] Washington signals diminishing willingness to resupply and underwrite Kyiv, and Russia’s influence continues to grow in the Global South.[3] Across the continent, populist and nationalist parties have translated migration pressures, cost-of-living shocks, and institutional mistrust into high-level governing roles. Economically, Europe’s expansion has lagged the United States, with weak productivity growth, fragile manufacturing competitiveness after the energy shock, and chronically low private investment weighing on potential output.[4]

Claims of declinism are surely not baseless, but rather they tend to overlook the complexities of geopolitical trends and the uncertain nature of historic transformation, often conflating relative decline with systemic collapse and undervaluing enduring advantages in military, technology, and finance in the United States. Declinism motivates, but it also distorts, substituting a simplistic fall story for a more accurate picture of messy rebalancing. Taken too far, it breeds threat inflation, overstating the “East’s” capabilities and ideological cohesion. Like the triumphalism it replaces, this binary mindset can become self-fulfilling and dangerous, encouraging overreaction abroad and corrosive fatalism at home.

Five Key Clarifications to Decode “East Rising, West Falling”

1: Not a Cold War Binary

Unlike the ideologically premised confrontation of the 20th century, today’s contest unfolds alongside dense interdependence and a more multipolar system, with issue-specific coalitions, hedging by “middle powers”, and selective technological controls rather than bloc-wide isolation. The “East” is a heterogeneous set of states with varied regimes, priorities, and partners. Countries often share no common ideology and align tactically where interests overlap while diverging elsewhere. Longstanding disputes and mistrust persist, including ongoing border tensions and competing maritime claims.

Additionally, the Soviet Union (USSR) was largely a hard‑power rival kept at arm’s length from Western markets; 21st‑century China competes across every front: diplomatic, economic, technological, political, and military, even as it remains embedded in global commerce and institutions. Unlike the USSR, China is deeply integrated into global supply chains—by 2023, China accounted for nearly 15% of global exports[5] and was the largest trading partner for over 120 countries, compared to the Soviet Union’s limited economic engagement with the West.[6] Even after nearly a decade of decoupling and derisking and recent escalations under President Donald Trump, the world remains tightly enmeshed.

2: Correlation Does Not Imply Causation

Attributing Western polarization, inequality, and institutional strain to the rise of Eastern powers overlooks the domestic side of these issues. Political attacks on research universities, such as President Trump’s feud with Harvard, or overzealous restrictions on student visas, are a case of the West injuring its own competitive advantages. In contrast, countries in the East, particularly China, are investing heavily in building new research universities and actively seeking to attract global talent, positioning themselves to benefit from the very opportunities that some Western countries are now restricting.

Similarly, although the “China shock” (China’s entrance into the WTO) did cause concentrated job and income losses in manufacturing, attributing the decline of the U.S. middle class solely to China ignores additional domestic factors such as automation, economic structural changes, declining union density, rising health-care costs, and policy decisions.[7] Today, concerns about a possible “China Shock 2.0”, driven by new waves of Chinese exports in sectors like electric vehicles, batteries, and green technologies,[8] reflect not only China’s industrial strength but also the fact that many Western countries have not similarly prioritized these sectors. Competitive pressures from the East may shape context and perception, but they are not the proximate causes of Western outcomes.

3: The East is Not Just China

Kishore Mahbubani, former Singaporean Ambassador to the United Nations, often uses the term “C.I.A countries,”[9] not referring to the Central Intelligence Agency, but China, India and ASEAN, to describe today’s “East”. This economic and strategic complexity finds concrete expression in wealth distribution trends: Mahbubani’s “C.I.A” bloc now anchors a seismic shift in global prosperity.

Over the past two decades, the global wealth middle class[10] has undergone a profound transformation (see Figure 1). Over the past two decades, its ranks surged by 78%, reaching 850 million people, with emerging economies driving this expansion. Today, China alone constitutes one-third of this class, while the rest of Asia (excluding Japan) contributes another quarter. This is a stark shift from the early 2000s, when the two regions combined represented just over a third. Though absolute membership in the middle wealth class grew across all regions, the dominance of Asia has sharply reduced the relative share of other parts of the world, underscoring the tectonic rebalancing of global prosperity. [11]

Figure 1: Global Middle Class Wealth Percentage by Region, 2003-2023

Source: Data from Allianz Research.

Additionally, while China is a dominant player in global trade and technology, India and ASEAN’s rapid industrialization and integration into global supply chains are increasingly shaping the world economy. ASEAN’s total trade value surged from US$871.8 billion in 2003 to US$3.56 trillion in 2023, nearly tripling to US$2.53 trillion within the first decade alone and expanding by over 40% in the subsequent ten years.[12] In 2022, 15 Asian-Pacific countries, including ASEAN nations, Australia, China, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand, launched the world’s largest free trade agreement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP), opening doors for collaborative intra-regional trade.[13]

India is also poised to harness an unprecedented demographic dividend, with its working-age cohort projected to constitute 68.9% of the national population by 2030. Over the coming decade, the country is expected to supply nearly a quarter (24.3%) of all new entrants to the global labor pool, a critical advantage as advanced economies grapple with workforce declines due to rapidly aging societies.[14] With a median age of 28.8 years (nearly a generation younger than China (40.1),[15] the EU (44.7)[16] or the United States (39.1)[17]), India gains dual strategic leverage: a cost-competitive labor reservoir for global industries and a burgeoning consumer base primed to drive domestic economic expansion.

Additionally, the rising presence of the Global South further complicates the concept of the “East” and the “West” as countries build new partnerships and assert their influence in global affairs. China has increasingly framed itself as part of this bloc. This strategic repositioning is marked by the recent emergence of quanqiu nanfang (全球南方) (a literal Chinese translation of “Global South”) in government communications. The phrase debuted in a speech by Foreign Minister Wang Yi in July 2023 when he declared, “As the largest developing country in the world, China is naturally a member of the ‘Global South’”. The phrase began to appear in state media a few months later. Furthermore, March 2025 saw the launch of the “China Development Research Council’s Global South Research Centre”, designed to serve as a platform for collaborative research and policy coordination with emerging economies.[18]

India has concurrently amplified its own vision of Global South leadership. In January 2023, India convened the inaugural “Voice of Global South Summit”, attracting 125 nations—including Latin American, African, and Asian states—to deliberate on shared priorities like climate equity and debt relief. Notably absent was China, reflecting the competitive undercurrents within the “East.”[19] Such dynamics reveal the Global South not as a cohesive counterweight to the West, but as a contested space where emerging powers like China and India vie for influence, further complicating simplistic East-West narratives.

4: Decline is a Relative Term

The apparent “decline” reflects a diminishing share of global power as large emerging economies grow more rapidly, rather than an absolute contraction in U.S. capabilities. The United States continues to be the dominant global power in military, technology, and finance. U.S. defense spending surpasses that of China and Russia combined, and is complemented by an unparalleled alliance network, global bases, and power‑projection capabilities.

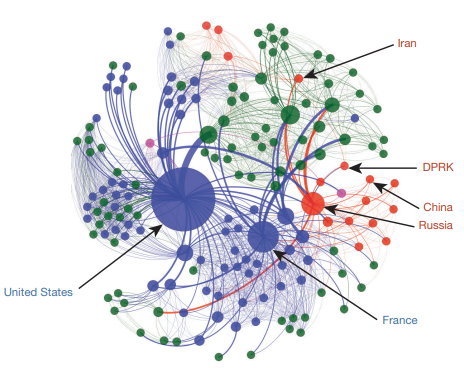

A 2024 RAND study examining U.S. global engagement from 1989 to 2017 found that while American allies dominated trade networks in only half the world, they maintained military superiority across all six regions. As shown in Figure 2, the U.S. alliance network functions as a global connective framework, integrating diverse security partnerships. This system includes both multilateral clusters and numerous bilateral agreements where the U.S. serves as a nation’s sole defense partner. In 2017, the U.S. network of 65 military allies accounted for 55% of global alliance system centrality, with each partner averaging 26 connections.[20] Although there has been significant disruption to economic alliances since President Trump returned to office in January 2025, these disruptions have not yet formally and significantly spilled over into the military or diplomatic spheres.

Figure 2: The Global Military Alliance in 2017

Source: Reproduced from the RAND Corporation’s 2024 report, “U.S. Alliance and Partner Networks: A Network Analysis of Their Health and Strength”

On the economic side, the dollar remains the preeminent reserve and invoicing currency, supported by deep and liquid treasury and equity markets and by its dominance in foreign‑exchange transactions. Although growing policy uncertainties, concerns over fiscal sustainability, and rising trade barriers have raised questions about economic stability, the dollar’s global usage has remained steady over the past five years, far surpassing the U.S. share of global GDP and trade. It continues to dominate financial innovation, serving as the primary anchor for stablecoins, and accounts for 58% of global foreign reserves in 2024, albeit down from a 2001 peak of 72%. The dollar also leads in banking, with roughly 55% of cross-border loans and 60% of deposits denominated in USD.[21]

In technology, the United States leads in advanced semiconductors, cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI), biotechnology, and venture capital, with firms and universities setting global benchmarks. A July 2025 report by the Belfer Center at Harvard Kennedy School shows that the U.S. retains its lead in critical technologies, as measured by the Global Tech Power Index, a data-driven model tracking advancements in AI, biotechnology, semiconductors, space, and quantum technologies. China, despite rapid progress, remains hindered by reliance on foreign semiconductor equipment, weaker private research ecosystems, and shallow capital markets.[22]

Suggestions of a rapid ebb in U.S. soft power and growing concerns about “de-risking” from U.S.-centric supply chains and finance do not acknowledge that such shifts remain limited in scope; the United States continues to wield outsized cultural appeal and agenda‑setting leverage across global media, education, standards, and capital flows. The global order may be increasingly multipolar, but its balance is still heavily asymmetrical.

5: Timeframes are Fluid

Historical experience shows that national trajectories are rarely linear and often punctuated by reversals. For example, Japan moved from an era of seemingly unstoppable growth in the late 1980s to decades of economic stagnation and demographic decline.[23] Similarly, India’s rapid acceleration after its 1991 liberalization[24] and the euro area’s recovery following the sovereign debt crisis highlight how sudden shifts can redefine national fortunes.[25] Today, the Chinese economy faces its own vulnerabilities, including mounting debt, a property market downturn, and persistent youth unemployment. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, public confidence in China’s long-term trajectory has also been challenged, with slower growth and greater uncertainty weighing on households and businesses.

Additionally, exogenous shocks can compress or elongate cycles. Pandemics rewire supply chains and labor markets. Wars, sanctions, natural disasters, and energy disruptions reprice risk and redirect capital. Technological breakthroughs or safety failures shift comparative advantage across sectors and regions. The accelerating pace of technological change, including the convergence of AI and nuclear capabilities, adds new layers of complexity and risk. Demographic changes, environmental crises, and other shared global challenges further complicate forecasts for all major economies. Relying on straightforward projections from recent trends risks overlooking the inherent fragility and unpredictability of both national and global trajectories.

Why This Nuance Matters

The five clarifications above are not semantics; they are a map for avoiding costly mistakes. They puncture reassuring but misleading binaries: East vs. West, China vs. the United States, democracy vs. autocracy, rise vs. fall.

Recasting this moment as a time for rebalancing keeps strategy grounded. It favors bounded competition over open-ended confrontation, targeted risk management over indiscriminate decoupling, and relationship stewardship over theatrical rupture. It also preserves space for practical cooperation where interests overlap, without denying enduring competition.

Binaries obscure what is, in reality, a dialectic; rival systems co-evolve, borrow from, and constrain each other, yielding Gestalt hybrids and partial syntheses rather than winner‑take‑all endgames. The task is not to predict a clean transfer of power from the “West” to the “East”, but to manage a new and dynamic global order and search for a “rebalancing” during a challenging and unpredictable era.

[1] Andrew Stanton, “J.D. Vance Warns Era of Uncontested U.S. Dominance Over,” Newsweek, May 25, 2025, https://www.newsweek.com/jd-vance-warns-era-uncontested-us-dominance-over-2076628.

[2] Bart van Eijden, “Europe’s Defence Dilemma: Ramping Up in a Fragmented Market,” Argon & Co, August 22, 2025, https://www.argonandco.com/en/news-insights/articles/europes-defence-dilemma-ramping-up-in-a-fragmented-market/.

[3] Kazushige Kobayashi and Kiyomi Osborn, “Is Russia Winning the Global South? Unpacking the Struggle for Survival in a Multi-Aligned World,” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, June 2025.

[4] António Dias da Silva et al., “Labour productivity growth in the euro area and the United States: short and long-term developments,” Economic Bulletin, Issue 6, 2024.

[5] Jeongmin Seong, “The global economy is resetting, China is repositioning itself to export innovative technologies, and its trading partners are more diverse,” Hong Kong Economic Times, April 22, 2024, https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/media-center/the-global-economy-is-resetting-china-is-repositioning-itself-to-export-innovative-technologies-and-its-trading-partners-are-more-diverse.

[6] Mark A. Green, “China Is the Top Trading Partner to More Than 120 Countries,” Wilson Center, January 17, 2023, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/china-top-trading-partner-more-120-countries.

[7] Scott Winship, “You Autor Know: Did the China Shock Reduce American Manufacturing Employment?” First World Problems, April 29, 2025, https://scottwinship.substack.com/p/you-autor-know.

[8] David Autor and Gordon Hanson, “We Warned About the First China Shock. The Next One Will Be Worse,” The New York Times, July 14, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/14/opinion/china-shock-economy-manufacturing.html.

[9] Kishore Mahbubani, BEYOND Expo 2023, Keynote Address, May 11, 2023, https://www.beyondexpo.com/2023/05/11/beyond-expo-2023-kishore-mahbubani-sees-challenges-in-a-rising-asia/.

[10] Defined by Allianz Research as individuals holding net financial assets between 30% and 180% of the worldwide average (€9,700 to €57,900 in 2023).

[11] Arne Holzhausen et al. “Allianz Global Wealth Report 2024: Surprising relief,” Allianz Research, September 24, 2024, https://www.allianz.com/en/economic_research/insights/publications/allianz-global-wealth-report-2024/distribution-progress.html.

[12] ASEANStats, “ASEAN Statistical Brief Volume VIII,” ASEAN Economic Community Department of the ASEAN Secretariat, May 2024, https://www.aseanstats.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/ASB-202405-03.pdf.

[13] The ASEAN Secretariat, “Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP),” The ASEAN Secretariat, updated 2025, https://asean.org/our-communities/economic-community/integration-with-global-economy/regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership-rcep/.

[14] “Reaping the demographic dividend,” EY India, April 11, 2023, https://www.ey.com/en_in/insights/india-at-100/reaping-the-demographic-dividend.

[15] “China’s Median Age,” World Economics, 2025, https://www.worldeconomics.com/Demographics/Median-Age/China.aspx.

[16] “Median age in the EU increased by 2.2 years since 2014,” EuroStat, February 21, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20250221-2

[17] Census.gov, “An Aging Nation: U.S. Median Age Surpassed 39 in 2024,” U.S. Census Department, June 26, 2025, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2025/06/metro-areas-median-age.html.

[18] Zha Daojiong, “China’s global south dilemma: Ally, leader or outsider?,” ThinkChina, August 13, 2025, https://www.thinkchina.sg/politics/chinas-global-south-dilemma-ally-leader-or-outsider.

[19] Ministry of External Affairs, “1st Voice of Global South Summit 2023,” Government of India, January 13, 2023, https://www.mea.gov.in/voice-of-global-summit.htm.

[20] King Mallory et al., “U.S. Alliance and Partner Networks: A Network Analysis of Their Health and Strength,” RAND Corporation, 2024, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA1000/RRA1066-1/RAND_RRA1066-1.pdf.

[21] Carol Bertaut et al., “The International Role of the U.S. Dollar – 2025 Edition,” U.S. Federal Reserve, July 18, 2025, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/the-international-role-of-the-u-s-dollar-2025-edition-20250718.html.

[22] Eric Rosenbuam et al., “Critical and Emerging Technologies Index,” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, June 2025, https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/2025-06/Belfer_CET_2.4.pdf.

[23] Masaaki Yoshimori and Russell Green, “What Happened to “Japan as Number One”?,” International Economics, August 26, 2016, https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/what-happened-japan-1.

[24] Harald Finger and Nujin Suphaphiphat, “India’s Path To Becoming One of the World’s Largest Economies,” International Monetary Fund, July 14, 2025, https://econofact.org/indias-path-to-becoming-one-of-the-worlds-largest-economies.

[25] European Central Bank, “Economic growth in the euro area is broadening,” ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 1, 2017, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/eb201701_focus01.en.pdf.