In 2025, federal workforce reductions disrupted several core agencies under the Department of Energy (DOE), igniting renewed concerns over the resilience of the United States’ energy systems and the integrity of national security protocols. These cuts, enacted under the broader reorganization agenda of the newly established Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), were promoted as necessary cost-saving measures within Donald Trump’s fiscal reform campaign.1 However, the nature and scope of the reductions have raised questions about the federal government’s ability to maintain stable energy governance, respond to emerging threats, and support the nation’s long-term transition toward a more secure and sustainable energy future.

As a central pillar of U.S. energy and security policy, the DOE is tasked with safeguarding nuclear materials, guiding clean energy innovation, and ensuring the reliability of the national power grid. The sudden contraction of its workforce has disrupted these functions, exposing serious vulnerabilities in operational capacity, regulatory oversight, and interagency coordination.2 Agencies deemed essential to national interest have also faced institutional uncertainty, prompting concerns about how strategic energy functions can continue under diminished staffing. While the administration’s rationale emphasizes efficiency, the uneven application of these cuts, particularly their concentration in departments linked to climate and energy policy, suggests a deeper politicization of bureaucratic restructuring. These developments highlight a growing disconnect between fiscal ideology and functional governance, demanding closer scrutiny of how workforce decisions shape the future of U.S. energy security.

This paper evaluates the impact of the 2025 federal workforce reductions, measuring the extent of weakened U.S. energy infrastructure. In analyzing the potential for nuclear oversight, regional grid instability, and the undermining of long-term clean energy initiatives, these developments could present a disconnect between the pursuit of administrative efficiency and the functional imperatives of national energy security. From a stability standpoint, the reductions in workforce affect institutional coherence while leaving essential agencies unprepared for emerging challenges. Addressing these vulnerabilities is crucial for the federal government’s role in energy governance and policy frameworks to safeguard public safety, energy sovereignty, and long-term environmental resilience.

Undermining of Nuclear Security

To streamline federal operations, the U.S. has restructured key oversight mechanisms in its energy sector, most notably in governing nuclear infrastructure. The 2025 wave of federal workforce reductions, introduced under the pretext of administrative efficiency and fiscal responsibility, has impacted the oversight mechanisms for safeguarding nuclear energy systems, suggesting a misalignment between governance efficiency and the federal responsibility to uphold energy sovereignty and public safety.3 Of particular concern are the cuts to the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), a semi-autonomous agency under the DOE tasked with ensuring the safety, security, and effectiveness of the nation’s civilian nuclear energy systems and nuclear materials management.4 The loss of personnel within this agency, particularly at high-level energy research institutions including Los Alamos and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories, signals not merely administrative downsizing but a substantive degradation of national energy security capacity and institutional operational readiness.5

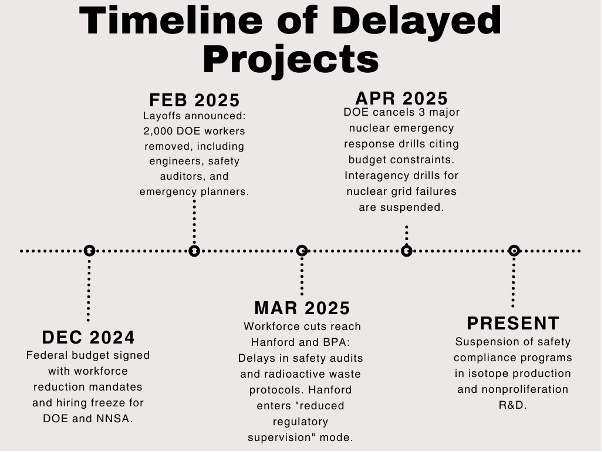

The layoffs have affected both long-term federal employees and probationary staff, including nuclear safety engineers, emergency energy response planners, and compliance auditors whose roles were central to protecting nuclear materials, enforcing regulatory standards, and managing energy-related emergencies. Their abrupt removal has disrupted essential regulatory timelines and left critical facilities without adequate personnel to ensure compliance, monitoring, and emergency response. Furthermore, around 2,000 DOE employees, with some working for the NNSA, were removed from their positions.6 Although Trump reversed the layoffs, the agency was unable to contact former employees who needed to be rehired.7

Figure 1: Delayed Infrastructure Projects Timeline

Source: Author’s creation using Canva

The impact is already visible in the Pacific Northwest region, where layoffs at the Hanford nuclear site and the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) have delayed critical infrastructure projects, safety audits, and radioactive waste management protocols. Hanford now operates under reduced regulatory supervision, exacerbating risks tied to unresolved nuclear waste storage issues.8 Meanwhile, Bonneville’s role in stabilizing the grid and integrating nuclear generation sources has been undercut by personnel losses, increasing the likelihood of operational disruptions during periods of peak electricity demand or cyber intrusions targeting nuclear-grid interdependencies.9 Given the challenges surrounding nuclear systems, ensuring safety requires skilled personnel and real-time judgment, factors that automation alone cannot substitute. As demonstrated by the 2012 Y-12 breach, over-reliance on automated systems can compromise even the most secure energy sites.10 This dynamic parallels key lessons from the 2011 Fukushima disaster, where institutional paralysis and delayed decision-making were more consequential than the physical damage itself in escalating the crisis.11 According to DOE-affiliated workforce data, the reductions have interrupted energy costs while impacting energy security.12 Emergency preparedness has also been affected, with workforce reductions impacting interagency energy response drills, including simulations of large-scale nuclear grid failures or targeted attacks on power plants.13 Budget constraints and staffing shortages led to the cancellation of vital contingency exercises in 2025, leaving the nation exposed in the event of a real crisis.14 Analysts warn that this lack of coordinated practice risks a dangerous false sense of readiness.

Institutionally, layoffs have disrupted oversight and research programs central to nuclear energy innovation, including nonproliferation, medical isotope production, and safety training. The suspension of contracts at the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations highlights the breakdown of linkages between energy innovation and oversight.15 These offices not only advanced clean nuclear technologies but also ensured compliance with projects funded under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The U.S. Government Accountability Office highlights a broader constitutional dilemma, arguing that the executive branch’s impoundment of appropriated clean energy funds may constitute a violation of the Impoundment Control Act of 1974.16 If deemed unlawful, the policy decisions driving workforce reductions could be challenged for undermining statutory energy objectives.

From a national security perspective, the strategic cost of dismantling federal nuclear energy capacity outweighs any short-term fiscal gains. Energy securitization theory underscores that energy systems, especially those tied to nuclear governance, are not just technical infrastructures but existential assets requiring state protection.17 In this light, the erosion of staffing and oversight at critical agencies compromises the state’s ability to treat energy as a matter of national survival, diminishing both resilience and global credibility in the energy domain.

While appeals to bureaucratic efficiency may satisfy short-term budgetary priorities, the resultant degradation of nuclear oversight institutions has exposed critical vulnerabilities in national energy governance. The resulting institutional thinning at the NNSA and affiliated DOE bodies has not only delayed key regulatory functions but also fractured long-term policy frameworks, eroding the federal government’s capacity to uphold its obligations under clean energy legislation and nuclear safety mandates.18 At a time of intensifying geopolitical threats and growing energy demand, the attrition of nuclear oversight capacity signals not only bureaucratic miscalculation but also a structural failure to integrate resilience, continuity, and security into national energy governance.

Threats to Power Grid Reliability and Regional Infrastructure

The U.S. energy transition, while strategically essential, now faces mounting operational risks as federal workforce reductions undermine the centralized institutions historically responsible for grid oversight and national energy coherence. Recent large-scale reductions in the federal workforce, executed under the Trump administration’s DOGE, have imposed a shift on the institutions historically tasked with sustaining and modernizing America’s energy infrastructure.19 This disruption has weakened BPA’s ability to manage the Pacific Northwest grid, particularly in high-voltage transmission and outage response.20

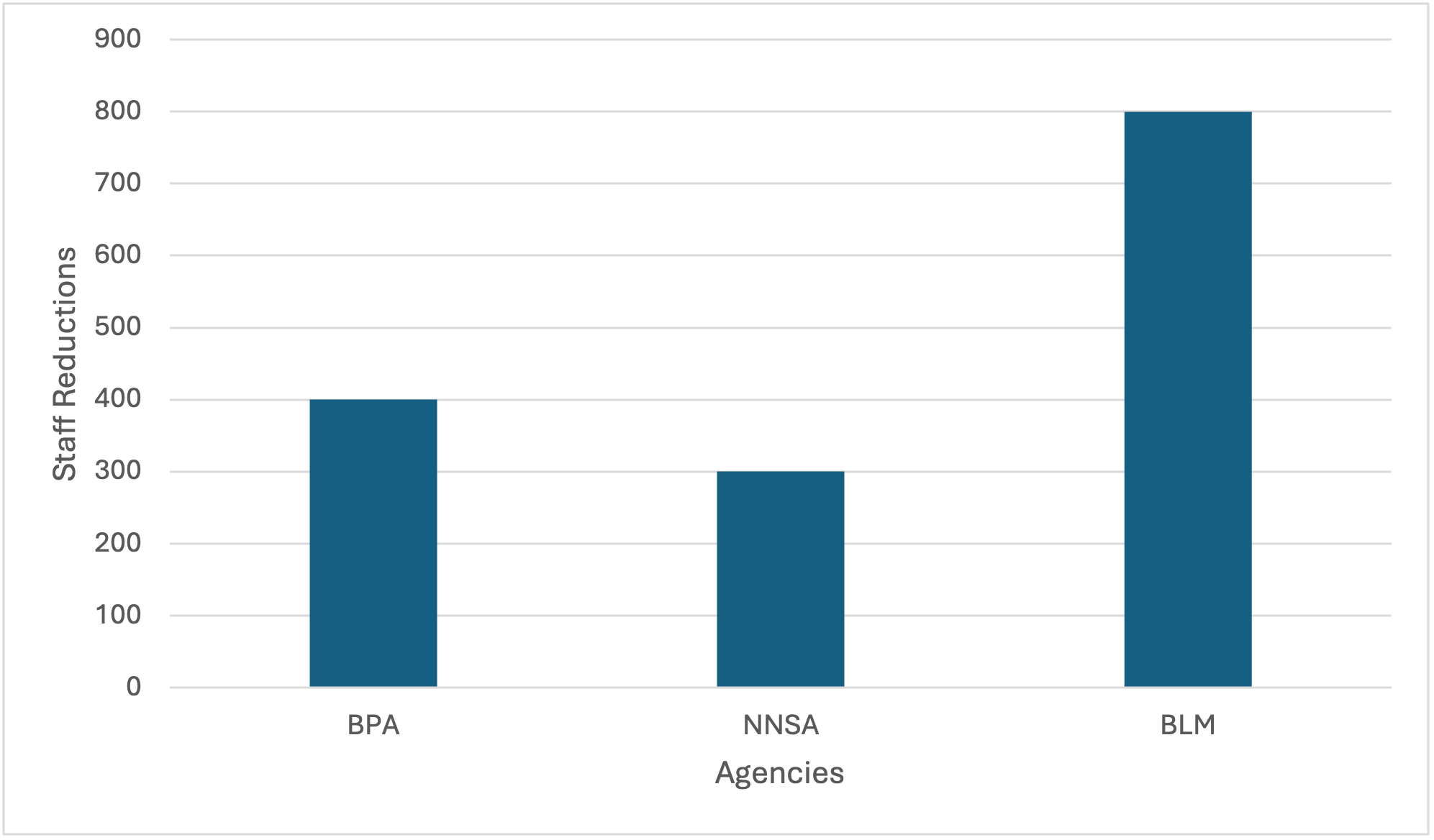

Figure 2: Federal Workforce Reductions

Source: Author’s creation using Microsoft SmartArt

Roughly 420 workers were terminated from BPA alone, accounting for 13% of 3,100 managing the Pacific Northwest’s electricity supply.21 Such reductions are not limited to BPA; over 2,000 employees in the Department of the Interior, including those in the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, both of which are instrumental in issuing permits and maintaining power generation infrastructure, have also been dismissed.22 Nationwide, more than 60,000 federal workers have been laid off since February 2025, with an additional 75,000 taking buyouts.23 This unprecedented downsizing threatens the federal government’s ability to uphold energy security mandates, maintain infrastructure continuity, and coordinate the integration of clean energy technologies. While advocates of a leaner government argue that states and private firms can compensate for federal pullback, the consequences suggest delayed energy integration, increased cyber vulnerabilities, and administrative bottlenecks across critical grid infrastructure.24 Particularly at risk are regionally integrated energy systems that rely on interjurisdictional coordination, which only the federal government is positioned to provide, highlighting a growing disconnect between administrative retrenchment and the functional imperatives of energy governance.

The operational challenges facing the BPA exemplify these broader systemic vulnerabilities. Operating over 15,000 miles of high-voltage transmission lines, BPA’s efficient performance depends on skilled staff capable of real-time grid monitoring, outage response, and long-term infrastructure planning.25 With a drastically reduced workforce, routine maintenance is being delayed, grid modernization initiatives are stalling, and project backlogs are swelling. These challenges reduce grid stability today and compromise future upgrades needed for a decarbonized economy.

Federal workforce reductions have also hindered progress in renewable energy integration, a cornerstone of the nation’s decarbonization strategy. The pause in disbursements under the IRA and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), mandated by Section 7 of Trump’s “Unleashing American Energy” executive order, has paralyzed projects designed to expand grid capacity through the integration of utility-scale solar arrays.26 These federal investments were foundational to many state and local efforts, especially in areas that lack the capital or regulatory capacity to deploy such technologies independently.27 As a result, energy transition timelines are slipping, and states that once stood at the forefront of clean energy leadership are now scrambling to reconfigure their development plans.

Moreover, the BPA and other regional transmission organizations are facing a compounding crisis in cybersecurity. The attrition of federal cybersecurity personnel and reduced funding for grid resilience initiatives have resulted in delayed software patching, limited breach response capacity, and increased exposure to SCADA system vulnerabilities across smart grid platforms.28 These cybersecurity vulnerabilities are emerging amid escalating geopolitical tensions and documented cyber intrusions by state-linked actors, including those affiliated with Russia, Iran, and China. A diminished federal presence hampers not just detection and mitigation, but also the ability to coordinate across jurisdictions in response to a breach. Without cohesive governance from agencies like the DOE and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, America’s grid grows more fragmented and less prepared for coordinated attacks or natural disasters.

Critics of the federal workforce model have argued that state governments and private actors can fill the operational vacuum. However, this perspective neglects the integrative function federal agencies perform in coordinating across state boundaries and ensuring standardization in disaster response. For instance, interstate electricity transmission projects, particularly high-voltage direct current lines, require unified oversight to align environmental reviews, synchronize technical standards, and allocate costs.29 Additionally, many states simply lack the technical workforce, regulatory infrastructure, or financial resources to absorb the sudden departure of thousands of experienced federal workers. This is particularly evident in rural and tribal communities, such as those in Alaska and New Mexico, where energy permitting and mineral extraction are not just economic drivers but essential to public service delivery.30 New Mexico’s federal land offices, which oversee drilling on federal land, contributing over one-third of the state’s general fund, are experiencing permitting delays.31 More than 22 tribes and nonprofits from Alaska to the Midwest, having around $350 million in federal funding, were impacted by frozen infrastructure projects.32 Furthermore, the BLM office in Utah has lost over 55 employees, including engineers, park rangers, and geologists since early 2025 due to mass resignations, firings, and rescinded job offers under federal workforce reductions.33 This bureaucratic inertia jeopardizes everything from clean energy projects and transmission upgrades to environmental safeguards and Indigenous land rights.

From a macroeconomic lens, the federal government’s role in sustaining local energy economies cannot be overstated. According to recent findings published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, approximately 86% of U.S. jobs are in sectors vulnerable to disruptions from the energy transition, with carbon-intensive communities exhibiting disproportionately high employment vulnerability.34 The concept of an Employment Carbon Footprint reveals that even regions not traditionally associated with fossil fuel extraction, such as manufacturing-heavy counties in the Great Plains, may suffer job losses due to federal divestment from energy and environmental services.35 Workforce reductions at agencies like the DOE risk compounding these vulnerabilities, especially in communities already excluded from just transition protections under the IRA.

There is also a profound distributive justice dimension to this problem. According to the Center for American Progress, every congressional district in the U.S. employs over 3,000 federal workers, the vast majority of whom are embedded within their local economies.36 These jobs support families, fund schools through income taxes, and sustain small businesses through consumption. Consequently, the dismissal of federal employees involved in grid oversight, regulatory review, and environmental enforcement has triggered economic contractions in local economies, particularly in rural regions. Moreover, the loss of institutional knowledge, particularly among senior civil servants and specialized engineers, cannot be easily or quickly replaced.

The erosion of institutional capacity in the energy sector compromises not only the domestic resilience but also the U.S. geopolitical credibility in advancing clean energy leadership. This institutional degradation risks impeding innovation in renewable integration and diminishing U.S. strategic competitiveness vis-à-vis global leaders, such as China and the European Union, in clean energy deployment and export capacity. Furthermore, a degraded federal apparatus limits America’s ability to respond effectively to climate-related disasters, such as wildfires, heatwaves, or hurricanes that increasingly threaten energy infrastructure in regions like the Gulf Coast and the Southwest.

Impact on Clean Energy Initiatives

The scale and speed of federal workforce reductions enacted in early 2025 under the “Workforce Optimization Initiative” have significantly impaired the operational capacity of several critical U.S. agencies, with particularly acute effects on the Loan Programs Office (LPO).37 Although publicly justified as efforts to streamline bureaucracy and limit regulatory capture, the reductions have materially constrained the federal government’s capacity to administer and implement clean energy. At the center of the disruption is the erosion of institutional oversight, particularly in the financing, administration, and monitoring of renewable energy projects that constitute a core component of the nation’s long-term strategy for energy independence and economic resilience.38

The LPO has historically played a pivotal role in catalyzing clean energy innovation, having facilitated over $35 billion in financing for projects across the solar, wind, nuclear, and hydrogen sectors.39 This core mandate has been structurally weakened, diminishing the LPO’s ability to evaluate proposals, manage disbursements, and conduct performance reviews across clean energy portfolios. Layoffs implemented in February 2025 reportedly resulted in the termination of approximately 45 employees from the LPO, an agency already operating with limited staff capacity.40 The effects of these reductions have been both immediate and structurally consequential, delaying the disbursement of IRA and IIJA funds and weakening the federal apparatus essential to maintaining the energy infrastructure. These delays disrupt the capital deployment timeline for renewable projects, disproportionately affecting rural and underserved regions where private-sector financing is contingent on federal loan guarantees. In parallel, the diminished capacity for program monitoring and oversight raises the risk of financial mismanagement, cost overruns, and inadequate compliance enforcement, thereby weakening public trust and policy effectiveness.41

Effective clean energy transitions depend on stable federal coordination, particularly during foundational stages of infrastructure deployment, interagency governance, and regulatory oversight, functions now affected by workforce instability. The loss of federal institutional capacity impairs the coordination mechanisms, due diligence processes, and co-financing structures necessary for effective public-private collaboration in clean energy deployment. From the standpoint of liberal institutionalism, which emphasizes the necessity of transparent and stable governance mechanisms,42 this institutional attrition constitutes a significant barrier to coherent climate governance while undermining the state’s ability to align national energy planning with long-term economic modernization strategies.

The stated rationale for the reductions, outlined in the 26 February 2025 memorandum issued by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM), was to eliminate non-statutory functions and prioritize the removal of positions not legally required.43 While the LPO is not a standalone statutory agency, its role is grounded in legislative mandates under the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007.44 Despite this, the LPO was not granted any exemptions under the new policy. The decision to target the agency as “non-essential” during funding lapses disregarded its strategic importance to national energy goals. As of mid-February 2025, approximately 1,000 probationary employees had been dismissed, more than 300 from the NNSA.45 Despite the partial reinstatement of staff in other DOE branches, more than 2,700 employees have applied for buyouts under the department’s deferred resignation program.46 These reductions coincided with the Department’s initial efforts to implement over $500 billion in clean energy investments authorized under the IRA.47 With limited personnel, the LPO now faces mounting bottlenecks in the approval and disbursement of funds for utility-scale solar farms, green hydrogen hubs, and advanced nuclear reactor projects. Prolonged project financing delays not only undermine investor confidence and emissions goals but also erode the strategic foundations of U.S. energy sovereignty and its credibility as a global leader in climate and energy diplomacy.

One such example is the DOE’s Hydrogen Hub program, designed to stimulate regional hydrogen economies. Due to staffing constraints at the LPO, project selection and fund disbursement have been delayed in key states such as Texas, Ohio, and Louisiana, regions where hydrogen infrastructure is critical to decarbonizing industrial sectors.48 Furthermore, the layoffs have significantly stalled review and approval processes within the DOE’s conditional loan portfolio, which includes over $200 billion in pending applications.49 Despite progress under the IRA, current projections indicate that the United States will fall 23% to 37% short of its 2030 emissions reduction target, undermining both national climate commitments and the credibility of its international leadership on climate action.50

The LPO’s role in de-risking early-stage clean energy technologies by providing critical financial guarantees that catalyze private sector investment has also been significantly weakened. With the dismissal of technical reviewers, legal experts, and environmental compliance officers, the agency is now less able to assess whether funded projects are meeting benchmarks for emissions reductions, economic development, and technological advancement. This institutional erosion is especially concerning given the historical lessons of prior clean energy cycles, where lack of oversight capacity, such as the Solyndra case, resulted in political backlash, diminished public trust, and weakened regulatory integrity.51 During the loan guarantee cycle under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2008-2012, high-profile project failures, most notably Solyndra, were attributed to insufficient due diligence.52 In response, the LPO instituted multiple layers of risk assessment and accountability mechanisms. These safeguards are now at risk of being dismantled, exposing both federal funds and taxpayer confidence to renewed uncertainty.

The potential consequences of diminished LPO capacity can also be illustrated by its past success stories. A prominent example is the LPO’s 2010 loan to Tesla Motors, which enabled the company to scale its electric vehicle production during a financially precarious period.53 This underscores how federal support for nascent technologies can yield transformative outcomes, a dynamic now threatened by the erosion of institutional capability. A further complication is the loss of institutional knowledge. Numerous reports confirm that the affected employees included mid-career specialists with extensive experience navigating the technical, legal, and regulatory complexities of the clean energy sector. The hiring constraints imposed by the January 2025 Presidential Memorandum, restricting recruitment to one position per four departures, have structurally impeded the agency’s ability to regenerate lost institutional capacity.54 President Donald Trump has extended the ongoing federal hiring freeze through mid-July, preventing agencies from filling vacant positions or establishing new roles for three months. 55

The broader policy implications extend beyond federal agencies. The National Governors Association has publicly raised concerns over the erosion of intergovernmental coordination frameworks, emphasizing the resultant delays in multi-level energy governance and implementation.56 Internationally, the workforce reductions may also impair the U.S. standing in global climate diplomacy. Whereas the previous administration had positioned green infrastructure as a cornerstone of foreign policy, the retrenchment under the current administration marks a strategic retrenchment that weakens the U.S. negotiating position at international climate forums and undermines its normative influence in multilateral climate finance structures. At forums such as COP29, the loss of federal momentum weakens the credibility of U.S. climate commitments and risks emboldening other major emitters to delay their own energy transitions. Undermining this model through domestic retrenchment compromises U.S. influence in shaping global finance norms and limits efforts to mobilize private capital for global decarbonization.

Critics, including energy policy experts, bipartisan stakeholders, and environmental NGOs, have argued that the decision to target the LPO was not merely a cost-saving measure but one rooted in ideological opposition to clean energy. This framing disregards the cross-partisan support historically enjoyed by clean energy programs, which are widely recognized for their contributions to national security, technological leadership, and economic growth. In response to growing legal challenges, multiple federal judges have issued rulings declaring aspects of the reduction-in-force (RIF) process unlawful, particularly in cases involving probationary employees.57 However, these decisions have not mandated full reinstatement of affected personnel, and future rounds of layoffs remain possible. Agency leaders now face legal uncertainty and mounting responsibilities without the staff fulfilling them. Congressional staff briefings obtained by the Congressional Research Service further suggest that applying RIF procedures to statutorily grounded agencies may have overstepped executive authority, raising legal and constitutional concerns regarding the balance between fiscal control and governance.58

Conclusion

The 2025 federal workforce reductions have revealed a profound misalignment between administrative efficiency initiatives and the structural imperatives of U.S. energy governance. While framed as a necessary response to fiscal constraints, the scale and concentration of these reductions in critical energy agencies have produced destabilizing effects across nuclear oversight, power grid reliability, and clean energy program implementation. The disruption to agencies such as the NNSA, the BPA and the LPO has not only weakened operational capacity but also affected the institutional continuity required to manage the evolving demands of energy security, infrastructure modernization, and climate resilience.

The consequences extend beyond administrative inefficiency. The reductions have delayed infrastructure projects, hampered emergency preparedness, introduced cybersecurity vulnerabilities, and undermined the disbursement of funding under the IRA and IIJA. The federal government’s reduced presence is particularly acute in rural, tribal, and economically vulnerable communities, where federal coordination plays a critical role in ensuring access to energy resources, permitting, and long-term investment planning. Additionally, the loss of specialized personnel has eroded institutional memory and technical capacity, further limiting the federal government’s ability to carry out legally mandated energy functions.

Considering the United States’ role in clean energy deployment and climate diplomacy, the erosion of federal institutional capacity poses strategic risks. The inability to meet domestic emissions targets weakens the credibility of international commitments and threatens to reduce the influence of the United States in shaping global climate governance frameworks. As the energy transition accelerates worldwide, the U.S. risks falling behind in technological competitiveness, regulatory innovation, and the global energy export market.

To restore resilience, the federal government must urgently reinvest in its energy workforce, uphold statutory obligations, and align budgetary decisions with national energy priorities. Stabilizing institutional capacity across agencies is essential to safeguarding national security, accelerating decarbonization, and preserving U.S. credibility on the international stage. Future policymaking must recognize that administrative streamlining, if disregarded from strategic imperatives, can undermine the very functions it seeks to optimize.

References

[1] The White House, “Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Works to Remake America’s Federal Workforce,” February 11, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/02/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-works-to-remake-americas-federal-workforce/.

[2] Robinson Meyer, “US DOE Could Lose a Record Number of Employees.” SolarPACES, April 10, 2025, https://www.solarpaces.org/us-doe-could-lose-a-record-number-of-employees/.

[3] U.S. House of Representatives, “Subject-by-Subject Breakdown of Trump’s Project 2025,” Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren, https://lofgren.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/lofgren.house.gov/files/evo-media-document/Stop%20Project%202025%20Task%20Force’s%20Project%202025%20Subject-by-Subject%20Breakdown_7.26.2024.docx-compressed.pdf.

[4] “US Energy Dept identifies thousands of staff at risk of DOGE cuts, AP reports,” Reuters, April 5, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-energy-dept-identifies-thousands-staff-risk-doge-cuts-ap-reports-2025-04-04/

[5] Edward Helmore, “Trump Administration Backtracks on Firing Nuclear Arsenal Workers,” The Guardian, February 15, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/feb/15/trump-administration-nuclear-arsenal-worker-firings.

[6] “Administration Lays off Federal Employees Across the Government,” NARFE, February 25, 2025. https://www.narfe.org/blog/2025/02/25/administration-lays-off-federal-employees-across-the-government/.

[7] Molly Bohannon, “Trump Administration Reverses Layoffs at These Federal Agencies—After Cutting Bird Flu, FDA Staff,” Forbes, February 24, 2025, https://www.forbes.com/sites/mollybohannon/2025/02/24/trump-administration-reverses-layoffs-at-these-federal-agencies-after-cutting-bird-flu-fda-staff/.

[8] EHN Curators, “Massive Solar Project Moves Forward at Contaminated Nuclear Site,” The Daily Climate, March 10, 2025, https://www.dailyclimate.org/massive-solar-project-moves-forward-at-contaminated-nuclear-site-2671297873.html.

[9] Courtney Sherwood, “Bonneville Power Administration Reverses 30 Job Cuts, Continues With Plans to Eliminate 430 Positions,” OPB, February 20, 2025, https://www.opb.org/article/2025/02/19/bonneville-power-administration-reverses-30-job-cuts-continues-with-plans-to-eliminate-430-positions/.

[10] U.S. Department of Energy, “Special Report: IG-0868,” August 29, 2012, https://www.energy.gov/ig/articles/special-report-ig-0868.

[11] “Fukushima Daiichi Accident,” World Nuclear Association. April 29, 2024, https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/safety-and-security/safety-of-plants/fukushima-daiichi-accident.

[12] Christa Marshall, “Leaked Doc: 56% of DOE Employees ‘Essential,’” E&E News by POLITICO, April 4, 2025, https://www.eenews.net/articles/leaked-doc-56-of-doe-employees-essential/.

[13] Jory Heckman, “Energy Department Extends Hiring Freeze, Deems 43% Workforce Non-‘Essential’ in Reorganization Plan,” Federal News Network, April 4, 2025. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/workforce/2025/04/energy-department-extends-hiring-freeze-deems-43-workforce-non-essential-in-reorganization-plan/.

[14] “Project 2025 — Department of Energy and Related Commissions — Annotated,” Environmental Data & Governance Initiative, 2025, https://envirodatagov.org/project-2025-department-of-energy-and-related-commissions-annotated/.

[15] Maeve Allsup, “What It Means to Cut the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations,” Latitude Media, April 4, 2025, https://www.latitudemedia.com/news/what-it-means-to-cut-the-office-of-clean-energy-demonstrations/.

[16] “What Is the Impoundment Control Act and What Is GAO’s Role?,” U.S. GAO, March 5, 2025, https://www.gao.gov/blog/what-impoundment-control-act-and-what-gaos-role.

[17] Jeffrey D. Wilson, “A Securitisation Approach to International Energy Politics,” Energy Research & Social Science 49 (March 2019): pp. 114–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.10.024.

[18] “GAO-25-107016, NATIONAL NUCLEAR SECURITY ADMINISTRATION: Explosives Program Is Mitigating Some Supply Chain Risks but Should Take Additional Actions to Enhance Resiliency,” GAO, March 2025, https://files.gao.gov/reports/GAO-25-107016/index.html.

[19] Elena Shao and Ashley Wu, “What We Know About the Trump Administration’s Cuts to the Federal Work Force,” The New York Times, April 14, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/03/28/us/politics/trump-doge-federal-job-cuts.html.

[20] Garrett Andrews, “Workforce Losses at BPA Will Have Grave Impacts on PNW Power Grid, Say Former Administrators,” Oregon Business, March 5, 2025, https://oregonbusiness.com/loss-of-14-bpa-workforce-will-have-grave-impacts-on-pnw-power-grid-say-former-administrators/.

[21] Gosia Wozniacka, “BPA Clawed Back Some Fired Workers but Blackout Concerns Remain,” Energy Central, February 27, 2025, https://energycentral.com/news/bpa-clawed-back-some-fired-workers-blackout-concerns-remain.

[22] “Musk’s Layoffs Shrink Workforce Needed for Trump’s Energy Dominance Agenda,” Pipeline & Gas Journal, March 13, 2025, https://pgjonline.com/news/2025/march/musks-layoffs-shrink-workforce-needed-for-trumps-energy-dominance-agenda.

[23] Kennedy Andara, “Thousands of Workers in Each Congressional District Could Lose Their Jobs to DOGE,” Center for American Progress, March 17, 2025, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/thousands-of-workers-in-each-congressional-district-could-lose-their-jobs-to-doge/.

[24] Anna Ribeiro, “US House Subcommittee Reviews State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program, Considers Adjustments for Impact,” Industrial Cyber, April 2, 2025, https://industrialcyber.co/threats-attacks/us-house-subcommittee-reviews-state-and-local-cybersecurity-grant-program-considers-adjustments-for-impact/.

[25] “Energy & Services,” Bonneville Power Administration, April 17, 2025, https://www.bpa.gov/energy-and-services.

[26] The White House, “Unleashing American Energy,” January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/unleashing-american-energy/.

[27] Julie Strupp, “Trump Funding Freeze Leaves IIJA, IRA Projects in Limbo,” Utility Dive, January 29, 2025, https://www.utilitydive.com/news/trump-funding-freeze-iija-ira-projects/738628/.

[28] Mohammad Ahmed Alomari, Mohammed Nasser Al-Andoli, Mukhtar Ghaleb, Reema Thabit, Gamal Alkawsi, Jamil Abedalrahim Jamil Alsayaydeh, and AbdulGuddoos S. A. Gaid. 2025. “Security of Smart Grid: Cybersecurity Issues, Potential Cyberattacks, Major Incidents, and Future Directions,” Energies 18, no. 1 (2025): 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18010141.

[29] U.S. Department of Energy, “Transmission Interconnection Roadmap Transforming Bulk Transmission Interconnection by 2035,” April 2024, https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2024-04/i2X%20Transmission%20Interconnection%20Roadmap.pdf.

[30] Mark Trahant and Indian Country Today, “How The Economy of Indian Country Impacts Local Communities,” High Country News, April 6, 2024, https://www.hcn.org/articles/economy-how-the-economy-of-indian-country-impacts-local-communities/.

[31] Garrett Golding, Diego Morales-Burnett, and Kunal Patel, “New Mexico Fuels U.S. Crude Oil Output, Funding for Local Programs,” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, March 24, 2025, https://www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2025/swe2504.

[32] Nate Perez, “Federal Funding Freeze Halts Key Infrastructure Projects in Tribal Communities,” WXXI News, April 14, 2025, https://www.wxxinews.org/npr-news/2025-04-14/federal-funding-freeze-halts-key-infrastructure-projects-in-tribal-communities.

[33] “The BLM in Utah Has Lost Park Rangers, Engineers and Geologists Since Trump Took Office. See Where.,” The Salt Lake Tribune, March 24, 2025. https://www.sltrib.com/news/environment/2025/03/24/utah-public-land-see-where-blm-has/.

[34] Kailin Graham and Christopher R. Knittel, “Assessing the Distribution of Employment Vulnerability to the Energy Transition Using Employment Carbon Footprints,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, no. 7 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2314773121.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Andara, “Thousands of Workers in Each Congressional District Could Lose Their Jobs.”

[37] “Friday Flash 02/28/2025 – the Coalition for Government Procurement,” February 28, 2025, https://thecgp.org/2025/02/27/friday-flash-02-28-2025/.

[38] World Economic Forum, “Navigating Global Financial System Fragmentation,” January 2025, https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Navigating_Global_Financial_System_Fragmentation_2025.pdf.

[39] Loan Programs Office, “LPO Overview,” 2024, https://www.energy.gov/lpo/articles/lpo-overview.

[40] Timothy Gardner and Valerie Volcovici, “Sweeping US Energy Department Layoffs Hit Offices of Loans, Nuclear Security, Sources Say,” Reuters, February 14, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/sweeping-us-energy-department-layoffs-hit-nuclear-security-loans-office-sources-2025-02-14/.

[41] “GAO-25-107743, HIGH-RISK SERIES: Heightened Attention to High-Risk Areas

Could Yield Billions in Savings and a More Efficient and Effective Government,” 2025. GAO, February 25, 2025, https://files.gao.gov/reports/GAO-25-107743/index.html.

[42] Rebecca Devitt, “Liberal Institutionalism: An Alternative IR Theory or Just Maintaining the Status Quo?” E-International Relations, September 1, 2011, https://www.e-ir.info/2011/09/01/liberal-institutionalism-an-alternative-ir-theory-or-just-maintaining-the-status-quo/.

[43] Russell T. Vought and Charles Ezell, “U.S. Office of Management and Budget Memorandum,” press release, February 26, 2025. https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/latest-and-other-highlighted-memos/guidance-on-agency-rif-and-reorganization-plans-requested-by-implementing-the-president-s-department-of-government-efficiency-workforce-optimization-initiative.pdf.

[44] Lowell Ungar, Garrett Brinker, Therese Langer, and Joanna Mauer, “Bending the Curve: Implementation of the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007,” American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, 2015, https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/publications/researchreports/e1503.pdf.

[45] Shannon Bond, Geoff Brumfiel, Andrea Hsu, and Cory Turner, “Sweeping Cuts Hit Recent Federal Hires as Trump Administration Slashes Workforce,” NPR, February 13, 2025, https://www.npr.org/2025/02/13/nx-s1-5296928/layoffs-trump-doge-education-energy.

[46] Robinson Meyer, “The Coming Bloodbath at the Department of Energy,” Heatmap News, April 10, 2025, https://heatmap.news/politics/doe-doge-buyouts.

[47] Adi Kumar, Sara O’Rourke, Nehal Mehta, Justin Badlam, Julia Silvis, and Jared Cox, “The Inflation Reduction Act: Here’s What’s in It,” McKinsey & Company, October 24, 2022, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/the-inflation-reduction-act-heres-whats-in-it.

[48] Leah Garden, “Climate Policy Outlook: 4 Stories to Follow This Week,” Trellis, April 7, 2025, https://trellis.net/article/climate-policy-outlook-4-stories-to-know-this-week/.

[49] Taite R. McDonald, , Kenneth Charles Cestari, Elizabeth M. Noll, Lara M. Rios, Patricia C. Duffy, Brianna Jones Rich, and James Steinbauer, “Status and Outlook for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office,” Holland & Knight, April 10, 2025, https://www.hklaw.com/en/insights/publications/2025/04/status-and-outlook-for-the-us-department-of-energys-loan-programs.

[50] “USA,” Climate Action Tracker, November 13, 2024, https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/usa/.

[51] Erik L. Olson and Harald Biong, “The Solyndra Case: An Institutional Economics Perspective on the Optimal Role of Government Support For Green Technology Development,” International Journal of Business Continuity and Risk Management 6, no. 1 (2015), available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280445172_The_Solyndra_case_An_Institutional_Economics_perspective_on_the_optimal_role_of_government_support_for_green_technology_development.

[52] U.S. House of Representatives, “The Solyndra Failure,” Committee on Energy and Commerce, August 2, 2012, https://legacy-assets.eenews.net/open_files/assets/2012/08/02/document_gw_01.pdf.

[53] U.S. Department of Energy, “TESLA,” 2024, https://www.energy.gov/lpo/tesla.

[54] The White House, “Reforming the Federal Hiring Process and Restoring Merit to Government Service,” January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/reforming-the-federal-hiring-process-and-restoring-merit-to-government-service/.

[55] Drew Friedman, “Agencies Will Still See Strict Limits on Recruitment Once Hiring Freeze Expires in July,” Federal News Network, April 18, 2025, https://federalnewsnetwork.com/hiring-retention/2025/04/agencies-will-still-see-strict-limits-on-recruitment-once-hiring-freeze-expires-in-july/.

[56] National Governors Association, “NGA Releases Playbook for Responding to Energy Emergencies,” March 19, 2025, https://www.nga.org/news/press-releases/nga-releases-playbook-for-responding-to-energy-emergencies/.

[57] David K. Young, John Gardner, and PJ Tabit, “Federal Workforce Reductions – Potential Impacts,” The Conference Board, March 21, 2025, https://www.conference-board.org/research/ced-policy-backgrounders/federal-workforce-reductions-potential-impacts.

[58] “Federal Workforce Downsizing: Voluntary and Involuntary Mechanisms,” Congress.Gov, February 10, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IN12505.