The concept of the Circular Economy (CE) has gained prominence in recent years, particularly in urban settings where sustainability and resource efficiency are major challenges. The transition from a linear economy to a circular one involves systemic changes in production, consumption, and waste management. European cities are at the forefront of this shift, employing policies and strategies to enhance material reuse, reduce waste, and improve resource efficiency. However, the integration of CE principles into spatial planning remains a complex and evolving process.

This paper explores the intersection of Circular Economy principles and spatial planning policies within European cities. The key research question guiding this analysis is: How and where might planning help with the Circular Economy’s implementation? To address this, the study is divided into several major sections. First, it examines the policy coherence between CE initiatives and urban planning frameworks, highlighting challenges and opportunities. Second, it discusses planning capacity, exploring the roles of governance structures and institutional frameworks in fostering CE transitions. Third, the paper delves into the concept of territorial integration, emphasizing the spatial dimensions of CE and the role of local governments in facilitating circular practices. Finally, it assesses the mobilization of stakeholders, including public authorities, private entities, and communities, in driving CE adoption and overcoming implementation barriers. By analyzing case studies from various European cities, this research sheds light on both the successes and shortcomings of current CE planning efforts. The discussion underscores the need for multi-level governance, stakeholder collaboration, and regulatory support to embed circularity into urban development.

The ISO standards that were introduced in 2024 demonstrate that closed circulation has become an indispensable part of the current economic model. A circular city seeks to create a resilient and sustainable urban environment by reducing waste, increasing resource efficiency, and encouraging material reuse and recycling. In contrast to a circular economy, which seeks to improve production systems’ efficiency and lessen their negative effects on the environment, a circular city is a locally governed system that is spatially bounded and concentrates on enabling systems of provision.

The design of circular cities incorporates crucial ideas like CO2 absorption strategies, green materials, recovery, recycling, sharing, and the growth of renewable energy communities, as well as proximity cities. By promoting material reuse and re-utilization to establish regional resource recycling networks, it aims to lessen environmental impacts[1]. The objectives of these cities are to increase resource productivity, preserve resource value for as long as feasible, and prevent losses by using effective business strategies.[2] Furthermore, circular city design activates dynamic networks of people, ideas, and spaces geared toward circular principles by transforming living environments for sustainability and resilience through design-led research and design thinking.[3] According to Niwalkar et al.,[4] cities may improve sustainability, generate employment opportunities, foster innovation, and further the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by implementing circular models. As a result, urban environments will become more robust and future-proof, tackling issues like population growth, shifting demographics, and rising demand for infrastructure and services. The absence of a precise definition for a circular environment is the primary criticism leveled at the existing circular economy initiatives in circular cities.[5] In reality, the absence of a concept for a circular city makes it more difficult to put policies that support a circular city into action. For instance, studies conducted in Malmö, Sweden, and Melbourne, Australia, caution that the influence of circular acts in urban strategic planning may be countered by a possible misunderstanding of the circular economy.[6]

Cities throughout Europe have been implementing more CE agendas in recent years.[7] Over 40 communities throughout Europe have signed the Circular Communities Declaration (CCDD), a joint project of ICLEI Europe and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Bringing these frameworks together is a common goal of integrating economic, social, and ecological goals into an urban development model that is more equitable, regenerative, and resourceful.[8] Crucially, the adoption of circularity as a profoundly spatial endeavor is required by the proposed transition from a global linear economy to a closed-loop local one.[9]

Although studies on spatial dimensions have begun, the emphasis has been on the local distinctiveness of interventions and the corresponding policy frameworks.[10] Hence, the planning system is one crucial area of study that is still little understood. According to earlier empirical studies on building hubs and circular maker spaces, regional planning systems and governing coalitions can either promote or impede urban circularity.[11] Circularity illustrates the intricate relationship between planning and policy, especially in redevelopment regions that are contentious and fragmented landscapes where emergent visions and established planning instruments collide.

Based on the difficulty of incorporating circularity goals into the current planning systems’ methods and urban and regional development paths, this analysis explores planning’s potential as a key area for the CE’s realization, as Van den Berghe and Verhagen[12] contend that all goals propelling the circularity transition are intrinsically linked to space, arguing that space should be acknowledged as the fifth or even transversal argument while Arauzo-Carod et al.[13] assert that regional issues are a crucial component of the Circular Economy. In this context, the main query is: How and where might planning help with the circular economy’s implementation?

Cities and regions have a key role to play as promoters, facilitators and enablers of circular economy

source: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/circular-economy-in-cities-and-regions.html.

Although circular economy ideas are not specifically included in any national policy, Williams[14] notes that they are somewhat covered in the existing national strategies regarding waste management, economic savings, and resource efficiency along supply chains. In this regard, the first intersection between CE and planning is the territory. The circular economy acquires its territorial component by taking into account the resources, possibilities, and limits of each region as well as its proximity to those elements.[15] The circular economy offers several advantages, some of which have geographical or spatial consequences. It contributes to regional development and the establishment of sustainability and territorial resilience by generating occupations that are more challenging to automate and move. Reuse, recycling, and waste reduction are crucial terms in an ecosystem where local resources are used more effectively and less often. Additionally, it lessens the need for a variety of supplies from the outside world. According to Chembessi et al.,[16] it also serves as a source of innovation. By enabling the territorialization of the production of goods and services and aiding in the reindustrialization of European territories, the circular economy helps to lessen reliance on the global supply of various materials, even though being close to resources geographically does not appear to be a sufficient criterion in and of itself. Given that the planning system continues to be the most crucial area and tool for implementing circularity, the question that needs to be answered is: under what circumstances may circularity then become a crucial component of planning approaches, and what territorial measures are already available?

A significant trend seen in many European contexts is territorial intermediation,[17] in which local governments create space for circularity by encouraging close relationships between stakeholders. It has also been demonstrated that combining municipal planning and procurement works well.[18] Circular economy research in cities has traditionally been seen via the epistemological lens of urban metabolism, which examines cities as though they were live biological systems that process resource inputs, throughputs, and outputs.[19] When it comes to the creation of cities and the control of resources inside them, urban metabolism has neglected the problem of influential power. The way ideas are framed determines the direction, content, and tools used to implement policy.[20] In addition to promoting bottom-up initiatives, urban planning currently needs to increase central authorities’ capacity to recognize new policy disputes and roadblocks and modify policy packages to resolve them.[21]

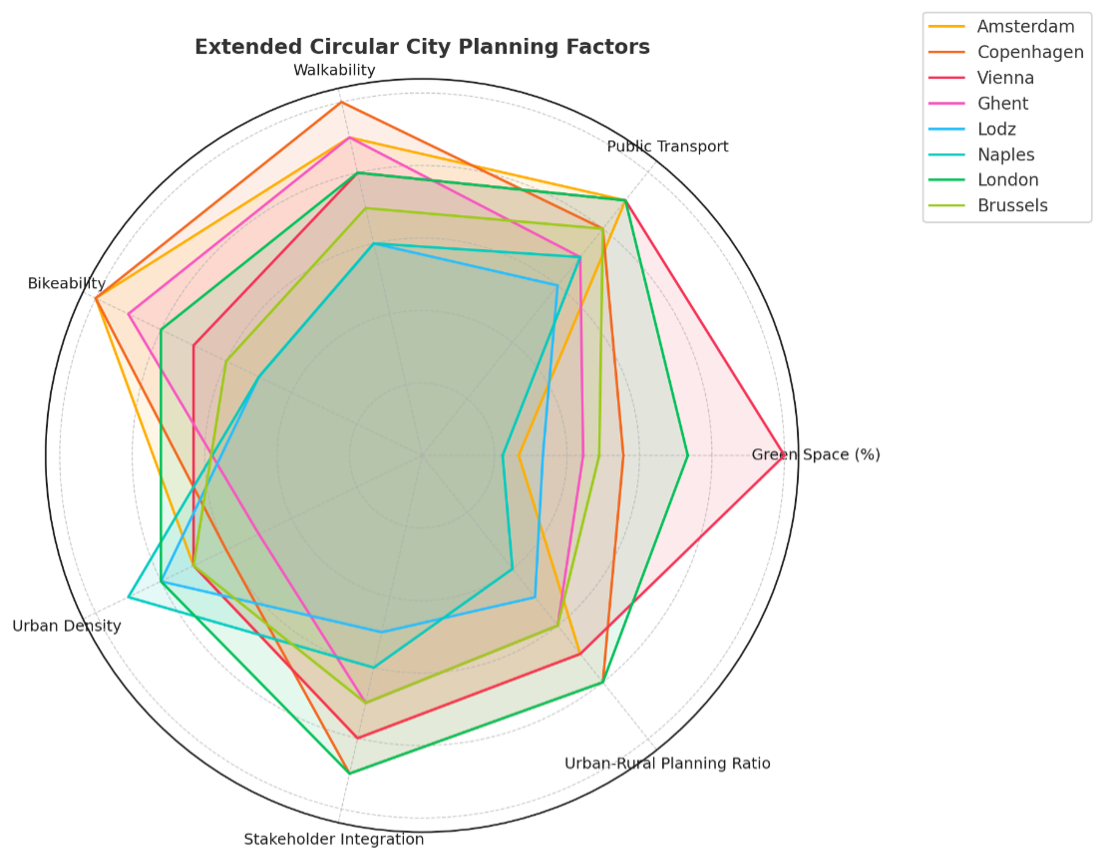

Vienna is the pioneer of green space allocation, reflecting a strong emphasis on parks and sustainable urban planning; Naples and Lodz appear with fewer green areas with a compact and dense building structure. In public transport efficiency in cities like Amsterdam, Vienna and London the only negativity is the bus system with high ridership, while in Lodz and Ghent, the transportation system is moderate but improving. London and Copenhagen show strong multi-level governance while Lodz and Naples still face challenges in governance and policy implementation. As a result, Copenhagen, Amsterdam and Vienna show a better balance in policy coherence between spatial planning and circular urban planning; Naples and Lodz need to improve green spaces, walkability and stakeholders’ integration; London and Brussels have high urban density but relatively strong governance and planning structures.

Current Mobilization for Transition in European Cities

The CE transition means that the whole multilevel socio-technological system and all of its subsystems—including the social system, which is made up of the political, cultural, and economic subsystems—will undergo drastic changes.[22] In metropolitan areas, achieving CE calls for a multidisciplinary, comprehensive strategy and the participation of stakeholders at many levels.[23] A substantial portion of Europe does not fall within the traditional “urban-rural” categorization scheme. These “in-between” or “in the middle” locations cannot be viewed as merely locations where urban and rural regions intersect. Due to conceptual ambiguity at the European level, circular city agendas can be as diverse as the cities implementing them.[24]

In contrast to places like Paris, which has extensive cross-sectoral policies, and London, which concentrates on industrial policy, Brussels Capital Region (BCR) shows a significant concentration on fundamental industries like building. Amsterdam’s transition process has led to the identification of growth areas and presents challenges for urban planning, not least in terms of the amount and quality of housing. A particular CE-related commencement may also result from the building problem. Naples in Italy, is distinguished by the existence of extensive infrastructural networks that coincidentally cross over into the area’s historical structure, transforming it from a rural to a peri-urban setting. Ghent is characterized by a high population density, with a notable distinction between the more rural parts and the highly populated inner city; nonetheless, because of the inner city’s close vicinity, it is heavily impacted by urban growth and mobility. Regarding Lodz in Poland, the component of the local municipality’s growth plan is the distribution of agricultural and forestation land for the construction of logistical facilities. Furthermore, it must be noted that the amount of municipal waste collected annually per resident is closely linked to the economic standing of each part of the nation.

Remarkable Notices

It is evident that the lack of an initial integration doesn’t adequately or fundamentally engage with the planning system; rather, it only results in an awareness of territorial potential and spatial constraints. Current CE efforts evoke an assimilation pathway of urban experimentation or instrumental experimentation,[25] in which the dominant regime itself has been the source of CE experimentation in planning, namely the openness to pilot projects and temporary usage. If the strategic and regulatory tasks of the planning system are not compatible, there may be an internal conflict between control and spontaneity that arises both at the regional level and inside the plans themselves. The study of regulatory features focused on the perceived applicability of the general legal frameworks’ comprehensiveness, the significance of explicit legal formalizations, and, lastly, the role of local autonomy in implementing place-based implementations.

It is clear that the ongoing gap between planning and policy runs the danger of halting the change in its tracks because, as scholars have noted policy planning implementation has historically differed considerably. Space is the foundation of circularity, whether it is considered the fourth pillar or the fifth, and planning continues to be the most crucial tool and indicator of the “seriousness” with which this development model is approached. Remaining loyal to its foundations, circular development eventually seeks to revolutionize the current economic system and its underlying planning system rather than existing in a vacuum or as a convenient substitute. To support urban development that incorporates broader socio-ecological values for equitable transitions, integrated policies must be implemented from the outset, across scales, and with a range of players. The local socio-spatial environment is crucial for the transition to CE and above all, local stakeholders effectively capture this.

Conclusions

The European experience in integrating Circular Economy principles into spatial planning offers several key lessons. Firstly, the success of CE policies depends on their integration into existing planning frameworks rather than operating in isolation. A lack of initial integration has led to fragmented awareness of territorial potential and spatial constraints. Secondly, cities that have successfully implemented CE policies, such as Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Vienna, demonstrate the importance of strong governance structures and multi-level policy coherence. Thirdly, strategic regulatory measures are crucial in overcoming the inherent conflicts between urban development needs and sustainability goals. Finally, fostering collaboration between local stakeholders and ensuring their active involvement in CE initiatives can enhance the effectiveness of policies and promote long-term sustainability.

Ultimately, the shift toward CE-driven urban planning requires a paradigm change, ensuring that spatial planning is not merely an instrument of control but an enabler of sustainable transformation. European cities must continue evolving integrated policies, engage diverse stakeholders, and recognize the socio-spatial environment’s role in achieving an equitable and resilient urban future.

[1] Johannes Kisser and Maria Wirth, “The Fabrics of a Circular City,” In An introduction to circular economy, (2021): 55-75.

[2] Elena Simina Lakatos, Yong Geng, Andrea Szilagyi, Sorin Dan Clinci, Lucian Georgescu, Catalina Iticescu, Lucian-Ionel Cioca (2021). “Conceptualizing core aspects on circular economy in cities,” Sustainability 13, no. 14 (2021): 7549.

[3] A. P. Chang, S. L. Chang, (2020, July). “Build up circular city planning index with EAM,” In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Vol. 531, No. 1 (2020): p. 012016.

[4] Amol Niwalkar, Tushar Indorkar, Ankit Gupta, Avneesh Anshul, Hemant Bherwani, Rajesh Biniwale, and Rakesh Kumar, “Circular economy based approach for green energy transitions and climate change benefits,” Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy, 89, no. 1 ((2023): 37-50.

[5] Joanna Williams, “Circular cities,” Urban Studies 56, no. 13 (2019): 2746-2762.

[6] Kathleen Bolger and A. Doyon, “Circular cities: exploring local government strategies to facilitate a circular economy,” European planning studies 27, no. 11 (2019): 2184-2205.

[7] Sharon Prendeville, Emma Cherim, and Nancy Bocken, “Circular cities: Mapping six cities in transition,” Environmental innovation and societal transitions, 26 (2018): 171-194.

[8] Martin Calisto Friant, Katie Reid, Peppi Boesler, Walter J.V. Vermeulen, and Roberta Salomone, “Sustainable circular cities? Analysing urban circular economy policies in Amsterdam, Glasgow, and Copenhagen,” Local Environment 28, no. 10 (2023), 1331-1369.

[9] Nuria Tapia-Ruiz, A Robert Armstrong, Hande Alptekin, Marco A Amores, Heather Au, Jerry Barker et al., “2021 roadmap for sodium-ion batteries,” Journal of Physics: Energy 3, no. 3 (2021): 031503.

[10] Sharon Prendeville, Emma Cherim, and Nancy Bocken, “Circular cities: Mapping six cities in transition.”

[11] Jasmin Baumgartner, David Bassens, Niels De Temmerman, “Finding land for the circular economy: territorial dynamics and spatial experimentation in the post-industrial city,” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 17, no. 3 (2024).

[12] Karel B. J. Van den Berghe and Teun J. Verhagen, “Making it Concrete: Analysing the Role of Concrete Plants’ Locations for Circular City Policy Goals,” Frontiers in Built Environment 7 (2021): 748842.

[13] Josep-Maria Arauzo-Carod, Ioannis Kostakis, and Konstantinos P. Tsagarakis, “Policies for supporting the regional circular economy and sustainability,” The Annals of Regional Science 68, no. 2 (2022): 255-262.

[14] Jo Williams, Circular Cities: A Revolution in Urban Sustainability (Routledge, 2021).

[15] Chedrak Chembessi, Sebastien Bourdin, and Andre Torre, “Towards a territorialisation of the circular economy: the proximity of stakeholders and resources matters,” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 17, no. 3 (2024).

[16] Ibid.

[17] Sebastien Bourdin, Danielle Galliano, and Amélie Gonçalves, “Circularities in territories: opportunities & challenges,” European Planning Studies 30, no. 7 (2022): 1183-1191.

[18] Jo Williams, Circular cities: a revolution in urban sustainability.

[19] David Wachsmuth, “Three ecologies: urban metabolism and the society-nature opposition,” The Sociological Quarterly 53, no. 4 (2012): 506-523.

[20] Michael Howlett, M. Ramesh, and Anthony Perl, Studying Public Policy: Principles and Processes (Oxford University Press, 2020).

[21] Felipe Bucci Ancapi, “Ex ante analysis of circular built environment policy coherence,” Buildings & Cities 4, no. 1 (2023).

[22] Patrizia Ghisellini and Sergio Ulgiati, “Managing the transition to the circular economy,” In Handbook of the circular economy (pp. 491-504), Edward Elgar Publishing, 2020.

[23] Sue Ellen Taelman, Davide Tonini, Alexander Wandl, and Jo Dewulf, “A holistic sustainability framework for waste management in European cities: Concept development,” Sustainability 10, no. 7 (2018): 2184.

[24] Karel Van den Berghe, Tanya Tsui, Merten Nefs, Giorgos Iliopoulos et al., “Spatial planning of the circular economy in uncertain times: Focusing on the changing relation between port, city, and hinterland,” Maritime Transport Research 7 (2024): 100120.

[25] Federico Savini and Luca Bertolini, “Urban experimentation as a politics of niches,” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 51, no. 4 (2019): 831-848.