The U.S.-China trade war grew more intense in 2018 due to several factors, including concerns about trade imbalances, intellectual property theft, and restrictions on market access. These issues led to several wars as both countries sought to assert their economic dominance. When the U.S. placed tariffs on a range of Chinese imports, China retaliated with tariffs of its own, sparking a protectionist trade war. In addition to disrupting global supply lines, this war harmed economic relationships, particularly in areas that were crucial to both nations. Both countries used economic means to achieve their geopolitical objectives during the trade war, ushering in a new era of strategic maneuvering. International markets have been affected by the conflict’s wider repercussions, which have increased uncertainty in the dynamics of global commerce and complicated the already strained geopolitical relations between the U.S. and China.[1]

The creation and functioning of contemporary industries and technology depend on critical minerals as raw materials. In industries like electronics, renewable energy, defense, and transportation, these minerals—both metallic and non-metallic—are essential. The production of vital technology, such as semiconductors, electric cars, and military systems, accounts for their strategic significance. However, these resources are vulnerable to supply chain interruptions, especially during times of geopolitical strife, because worldwide production is frequently concentrated in a limited number of nations. Concerns about pollution, sustainability, and moral extraction practices are also brought up by the effects of mining and processing essential minerals on the environment. As the global demand for these minerals increases, legislators and corporate executives are becoming increasingly concerned about maintaining a safe and moral supply chain.[2]

Numerous minerals are essential for modern industrial and technical operations. Because they are used to make permanent magnets, which are necessary for devices like wind turbines and electric cars, rare earth elements (REEs) are especially important. Lithium is essential for creating high-efficiency lithium-ion batteries, while cobalt and nickel are also important for energy storage and performance. Other minerals, such as graphite and manganese, are essential for a variety of industrial uses and battery technology. Furthermore, advanced industrial, aerospace, and renewable energy solutions depend on niobium, tantalum, platinum-group elements, tungsten, titanium, and aluminum. Together, these minerals promote technological advancement and highlight their strategic importance in international supply networks and economic expansion.[3]

Importance of Critical Minerals in the U.S.-China Trade Dynamic

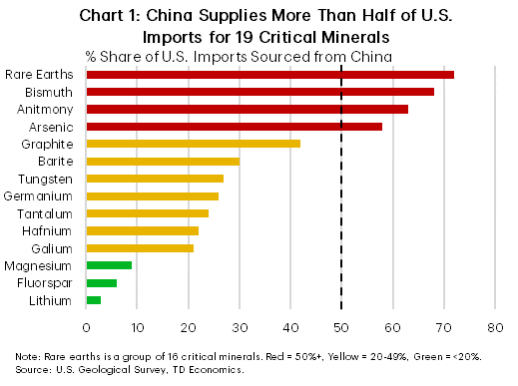

Figure 1: China’s Supply of Critical Minerals to the U.S.

Source: TD Economics, https://economics.td.com/us-trade-critical-minerals.

The intricate and varied function of essential minerals in the trade relationship between the U.S. and China reflects the resources’ increasing significance in both the geopolitical and commercial spheres. Vulnerability in the supply chain is one important factor. Securing trustworthy sources of vital minerals is strategically important for high-tech industries like electronics, renewable energy, and defense, and both the U.S. and China understand this. Global supply chains have vulnerabilities because of the trade war, especially for resources like lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements. Industrial and technological advancement may suffer significantly if the supply of these resources is disrupted.[4] Since control over vital mineral resources has evolved into a tactic for gaining an advantage in trade discussions, economic leverage also plays a big part in the U.S.-China trade dynamic. There is more competition for access to these commodities as both countries work to diversify their supply sources and lessen their reliance on one another. Each country aims to influence the others by controlling access to vital resources, either through domestic production or international cooperation. To guarantee a consistent supply of these vital resources, this competition has prompted investments in mining, refining, and exploration as well as the creation of other trade routes.[5]

Another important factor fueling the U.S.-China struggle for vital minerals is technological improvement. These materials are essential to the creation of cutting-edge technologies, including quantum computing, 5G networks, electric cars, and artificial intelligence (AI). Securing a steady supply is crucial to preserving the technological advantage of the U.S. and China, which have made significant investments in technologies that depend on vital minerals. The wider geopolitical rivalry, in which technological superiority is increasingly seen as a crucial component of global power, is intricately linked to this competition for resources.[6]

The U.S.-China trade dynamic pertaining to vital minerals is further complicated by national security concerns. Both countries import a lot of minerals, particularly rare earth elements. Calls for more self-sufficiency have been sparked by the serious national security threats this dependency has brought about. Efforts to lessen reliance on foreign sources have been sparked by the U.S.’ reliance on China for rare earth elements. In a similar vein, China has worked to lower risks by ensuring reliable supply chains and lowering reliance on imports from nations that might not share its strategic objectives.

Both nations are attempting to improve their own mining capacities, form alliances with nations that possess abundant natural resources, and guarantee reliable global supply chains to tackle these issues. As both countries work to reach ambitious renewable energy objectives while navigating the competitive global resource landscape, the increased demand for essential minerals—particularly in the context of the green energy transition—adds another layer of complication to the U.S.-China trade relationship.[7]

The U.S.-China Critical Minerals Nexus

With major ramifications for both countries and the global economy, the U.S.-China critical minerals nexus serves as a crucial battlefield in the larger framework of geopolitical and economic competition. China has significant influence in the high-tech and renewable energy sectors, which are essential to economic growth and innovation, due to its supremacy in the extraction, refinement, and supply of vital minerals. The U.S. is actively working to diversify its sources, promote domestic manufacturing, and fortify its international ties to lessen its need for Chinese imports. Wide-ranging effects of this competition include affecting international supply chains, the rate of technical development, and the shift to sustainable energy.[8]

China’s Dominance in Critical Minerals

In the market for important minerals, China has solidified its position as the world leader, especially in processing and refining capabilities that are essential for contemporary technologies and industries. China demonstrated its strategic control over vital resources by dominating the production of 30 of the 50 minerals the U.S. had designated as crucial by 2022. Additionally, it manages over 85% of the global rare earth element (REE) processing capacity. This domination highlights China’s influence in the current geopolitical and economic conflict as well as its crucial role in forming the world’s essential minerals landscape.[9]

China’s dominance in the global market is largely due to its monopoly in the processing of key heavy rare earths like dysprosium and terbium as well as light rare earths like neodymium and praseodymium. When Deng Xiaoping realized the critical importance of rare earths in the 1990s, he kick-started the process to reach strategic domination on the market. China has created a vast ecosystem around these minerals over the years, overseeing every phase from extraction to the creation of finished products, especially rare earth magnets, which are essential for sectors like renewable energy, electric vehicles, and defense technologies. China currently has a significant edge in controlling supply chains for these vital minerals.[10]

China’s Export Restrictions

China’s harsh export restrictions on vital “dual-use” technologies on 3 December 2024, increased tensions in the current trade war with the U.S. Among these actions was a prohibition on the export of antimony, gallium, and germanium—three vital minerals needed for a variety of high-tech sectors. Since it specifically targeted vital resource shipments to the U.S., this signaled a dramatic change in China’s trade strategy. The prohibition is a strategic reaction to growing economic and geopolitical tensions between the two nations since these minerals are essential for sophisticated manufacturing, technical innovation, and U.S. defense technologies.[11]

China has tightened rules on the export of graphite, a crucial component in the creation of batteries and other industrial applications, in addition to banning some minerals. The U.S. is largely dependent on Chinese suppliers of these minerals, which increases worries about supply chain vulnerabilities worldwide. China’s capacity to use its position as a major provider of vital raw materials to its advantage in economic and geopolitical conflicts is demonstrated by its growing attention to this role. Limiting exports of these essential minerals might cause market disruptions around the world and force the U.S. to look for other suppliers or accelerate attempts to build up its own production capacity.[12]

U.S. Strategy to Counter Chinese Dominance

Understanding the strategic significance of ensuring a steady and varied supply, the U.S. has adopted a thorough and multifaceted approach to reducing its reliance on China for essential minerals. Increasing domestic production of vital minerals through programs to open new mines, advance mining technology, and promote resource extraction innovation is a crucial component of this plan. To gain access to vital minerals that are not under Chinese control, the U.S. is also placing a higher priority on diversifying its supply chains by fortifying alliances with allies like Australia, Canada, and several European states. To lessen dependency on new mining and contribute to the development of a more sustainable supply chain, initiatives are also being made to promote the recycling of essential minerals. These tactics seek to lessen vulnerabilities and guarantee that the U.S. can maintain its competitiveness in the expanding global market for vital minerals, especially those required for clean energy transitions and innovative technologies.[13]

By leading programs like the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) and the QUAD Critical Minerals Partnership Act, the U.S. has taken the initiative to reduce its reliance on China for vital minerals. These programs aim to build more robust supply networks by encouraging collaboration among allies. Australia, which is abundant in essential minerals, has emerged as a crucial partner as the U.S. has extended subsidies to “friendly” nations.[14] In addition, the creation of the nonpartisan Critical Minerals Policy Working Group is indicative of a determined attempt to develop policies that would protect and diversify the country’s vital mineral resources, guaranteeing technical competitiveness and energy security. The U.S. hopes to improve mineral security and advance geopolitical stability by fortifying these foreign alliances and lowering the risks associated with an excessive reliance on Chinese resources.[15]

U.S. Strategy to Reduce Dependence

With an emphasis on both legislative measures and investments in domestic production capacity, the U.S. has created a comprehensive plan to reduce its dependency on China for essential minerals. This plan calls for international collaboration with allies, additional financing for mining, exploration, and processing technologies, and regulations to ensure a more robust supply chain. These initiatives seek to lessen reliance on Chinese exports, promote cooperation in mining, recycling, and technology development, and diversify supplies of essential minerals.[16]

Policy Initiatives

Through executive directives and legislative acts, the Trump and Biden administrations both significantly addressed vulnerabilities in the vital mineral supply chain. The Trump administration’s Executive Order 13817 sought to recognize and mitigate the risks associated with disruptions in the mineral supply. In the meantime, President Biden’s Executive Order 14017 placed a strong emphasis on lowering reliance on foreign suppliers, especially China, and bolstering the U.S. supply chain for vital minerals.[17] Legislative initiatives, including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act, have allotted funds and offered incentives to improve domestic production and processing of vital minerals under the Biden administration. To guarantee a safe and dependable supply of these vital resources, the Department of Commerce also created a federal strategy that prioritized innovation, domestic extraction support, and the development of global alliances to reduce supply chain vulnerabilities. The U.S.’ strategic position in this crucial area will be strengthened as a result of these efforts, which show a coordinated approach to acquiring vital minerals for the energy, defense, and technology sectors.[18]

Trump Administration’s Mineral Policy

The Trump administration prioritized supporting American businesses and workers while boosting U.S. mineral production, especially extraction. Imposing tariffs on mineral imports, expediting the mining project permitting procedure, and offering financial incentives for indigenous mineral extraction were some of the main tactics.[19] Using legislative tools, including the International Emergency Economic Powers Act and Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, the government raised tariffs to lessen reliance on foreign minerals, especially those originating from China. By repealing some environmental laws and allowing additional federal lands to be exploited, it also made the permitting process for mining ventures easier. The Trump administration also increased eligibility for already-existing programs, such as the Advanced Technology Vehicle Manufacturing program, shifted government financing toward domestic mining projects, and instituted Buy American laws to encourage domestic production. The goal of these initiatives was to fortify the indigenous mineral supply chain and lessen dependency on imports.[20]

At the same time, President Trump declared that he would start imposing a 10% tariff on Chinese imports on 1 February 2025, citing China’s inability to stop the supply of fentanyl as the primary justification. It is anticipated that this action will intensify trade tensions, which are already elevated by worries over China’s hegemony in vital minerals.[21] About 70% of the world’s production and 90% of its processing of rare earth elements, which are essential for the development of electronics, automobiles, and military hardware, are controlled by China. The stakes in the continuing trade dispute are raised by this increasing reliance on China for essential minerals.[22]

Domestic Mining and Processing Investments

With an emphasis on increasing production, increasing manufacturing capacity, and improving recycling initiatives, the Biden administration took strong action to fortify the domestic essential mineral supply chains in the U.S. The administration wanted to lessen dependency on foreign sources, especially China, and revive the native mining sector through significant investments. This approach involves promoting advancements in extraction techniques, material efficiency, and recycling procedures as well as the advancement, development, and application of cutting-edge technology throughout vital mineral supply chains.[23] The Defense Production Act’s expanded capitalization, which offers vital financial support to guarantee the production of minerals required for national security, is a crucial part of this strategy. The administration’s dedication to bolstering the country’s mineral independence and safeguarding its technological and defense future was demonstrated by these concerted measures.[24]

Technological Innovations

Beyond mining investments, efforts are being made to improve the U.S. critical minerals supply chain through technological advancements in recycling, reprocessing, and alternative technologies. Technological developments in recycling and reprocessing are intended to reduce reliance on primary mineral sources by recovering valuable minerals from waste.[25] Furthermore, the goal of research on technology alternatives to essential minerals is to find substitutes that can lessen supply chain stress. To make these operations more effective and sustainable, efforts are also being made to improve the extraction, separation, purification, and alloying processes.[26]

Global Implications and Responses

Many nations are reevaluating their supply strategy because of the U.S.-China competition in essential minerals, which is changing the dynamics of the global market. Large economies, including the European Union, are working to secure alternative supply chains, increase domestic industrial capabilities, and lessen their dependency on China. These nations are also promoting international collaborations to lessen the dangers of China’s hegemony in response to geopolitical difficulties.[27]

Resource-rich countries like Mexico, Chile, Zimbabwe, and Indonesia are also taking action to tighten control over their mineral resources. To encourage domestic processing and preserve greater value from their resources, several countries are enacting nationalization laws and export limitations. A major participant in the market for vital minerals, Australia is reevaluating its geopolitical alliances, especially with China, and moving closer to U.S. interests. This shift is motivated by a desire to broaden its alliances, promote economic stability, and aid in the diversification of global supply.[28]

Outlook

Increased strategic competition in the future of vital minerals is anticipated to characterize the U.S.’ relations with China in this domain, particularly given Donald Trump’s comeback as president. The competition will certainly intensify under a second Trump administration as policies prioritize protecting American supply chains and lowering dependency on imports of vital minerals from China. In response, China might use its hegemony in the world market for vital minerals to strengthen its geopolitical clout and undermine American policy. As both countries aim to establish control over this crucial industry, this dynamic will impact international trade patterns, create new alliances, and change global supply chains.[29]

Escalating Trade War

With vital minerals as a major concern, trade tensions with China are predicted to worsen as Trump has returned to the White House in 2025.[30] A 10% tariff on fentanyl exports and a 60% tariff on what Trump views as unfair trade practices are two examples of the potential reintroduction and expansion of tariffs on Chinese goods by his administration. China may take significant retaliatory action in response to these steps, especially in the key minerals sector where China is a global leader. The U.S. and its allies’ supply chains would become even more vulnerable as a result, and geopolitical competition over vital resources for the defense, renewable energy, and advanced technology sectors would intensify.[31]

China has already shown that it is prepared to employ its geopolitical dominance over vital minerals. China banned the export of important minerals to the U.S. in December 2024, including graphite, gallium, germanium, and antimony. This action shows that China is prepared to use its place in the global supply chain to apply economic pressure, especially considering the current trade disputes with the U.S. The prohibition emphasizes the vulnerability of nations like the U.S., which mainly depend on these resources for economic and technological uses, as well as the growing significance of resource control in geopolitical disputes.[32]

Supply Chain Disruptions

Global supply chains are likely to be disrupted by the prolonged trade war and export restrictions, especially for companies that rely on vital minerals. When supply shortages meet growing demand, particularly from industries like clean energy and defense, these disruptions may result in higher price volatility.[33] Lack of vital resources like lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements may impede the switch to renewable energy sources and have an impact on technological advancement. Because the defense industry depends so largely on these minerals for sophisticated weapons and defense systems, it might find it difficult to find substitute sources, which could jeopardize national security. Geopolitical conflicts over resource access may worsen because of these difficulties, which may compel American businesses to change their manufacturing methods or look for alternative supplies.[34]

The U.S. and its allies are stepping up attempts to diversify supply chains in reaction to China’s hegemony in the vital minerals market. Increasing local production, establishing new alliances with mineral-rich nations, and funding recycling and circular economy projects are some of these strategies. Countries that are rich in key minerals, such as Vietnam, Brazil, and India, are becoming strategically important as rivalry for these resources heats up, which could result in new geopolitical alignments and changes in international relations.[35]

Need for Global Cooperation

There is growing awareness that international cooperation is essential for risk mitigation and supply chain stability in the face of intensifying competition for important minerals. To share financial responsibilities and lower individual risks related to mineral extraction and processing, nations and businesses are increasingly looking at joint investment frameworks.[36] The goal of partnerships with developing countries that possess important minerals is to promote agreements that are transparent, stable, and advantageous to both parties. A more stable trading environment might be achieved by voluntary agreements to minimize the use of export controls, which would lessen the uncertainty caused by abrupt export limits. Furthermore, encouraging recycling programs and circular supply chains offers a viable means of lowering dependency on primary resource extraction and promoting more environmentally friendly methods. Principles that strike a balance between resource security, environmental sustainability, and economic cooperation will probably serve as the foundation for these international initiatives.[37]

Conclusion

The quest between the U.S. and China for access to crucial minerals has intensified, and both countries are using calculated tactics that interfere with international supply chains. To maintain its supremacy, China has restricted the export of vital minerals like gallium, germanium, and graphite. In response, the U.S. has imposed tariffs, which has caused uncertainty for sectors like technology, defense, and clean energy that depend on these resources. Global markets could become unstable because of this. Concerns about national security have been raised by the U.S.’ significant reliance on China for vital minerals, which make up more than 60% of its imports of rare earth elements. To diversify its supply chains and lessen dependency, the U.S. is concentrating on increasing local production, establishing foreign alliances, and investing in recycling technology.

International collaboration is necessary to secure vital mineral supply chains. The necessity of cooperative frameworks is shown by programs such as the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative and the Quad Critical Minerals Partnership. These frameworks can guarantee fair trade practices while lowering risks and expenses and encouraging collaborative investments. By striking a balance between commercial interests and national security, voluntary agreements to restrict export prohibitions could further stabilize the world’s mineral markets. The need to secure vital mineral supply chains is growing as the world’s drive for sustainable energy grows. The difficulty is striking a balance between collaboration and competitiveness, particularly considering persistent geopolitical tensions. Long-term economic stability and the advancement of green energy technology will depend on collaboration on vital minerals, even if the second Trump administration continues to prioritize tariffs and other strategic measures.

The goal of Trump’s essential minerals plan is to increase domestic production and processing while lowering reliance on imports, especially from China. This administration wants to encourage investment in mineral ventures, increase exploration activities, and simplify mining rules. The goals of these programs are to improve national security and economic independence in the U.S. The U.S. may maintain tariffs and limitations on Chinese mineral imports, change ATVM and Title 17 programs to encourage domestic extraction, and put security issues ahead of climate concerns in the second Trump administration. This approach highlights a change toward enhancing American capacity to protect vital resources and lessen reliance on adversaries in the geopolitical arena.

[1] Niyamat Ullah, Amir Jan, and Abdul Waheed, “Role of Economy in Foreign Policy: An Appraisal of US-China Trade War in the Prism of Political Economy,” Journal of Asian Development Studies, 2024, https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:268829264.

[2] Sarah M Hayes and Erin A. McCullough, “Critical Minerals: A Review of Elemental Trends in Comprehensive Criticality Studies,” Resources Policy (2018). https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:158070669.

[3] Chester J. Weiss and Alan G. Jones, “Introduction to This Special Section: Critical Minerals Exploration,” The Leading Edge 42, no. 4 (2023): 236-237, https://library.seg.org/doi/full/10.1190/tle42040236.1.

[4] Yuanhao Yang, “Impacts of the U.S.-China Trade War on Lithium-ion Battery Supply Chains: A Network Analysis Approach,” International Journal of Global Economics and Management, 2024, https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:274765945.

[5] Joseph Majkut, Jane Nakano, Maria J. Krol-Sinclair, Thomas Hale, and Sophie Coste, “Building Larger and More Diverse Supply Chains for Energy Minerals,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 19, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/building-larger-and-more-diverse-supply-chains-energy-minerals.

[6] U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, “U.S.-China Competition in Emerging Technologies,” 2024, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2024-11/Chapter_3–U.S.-China_Competition_in_Emerging_Technologies.pdf.

[7] Jon Bateman, “U.S.-China Technological “Decoupling”: A Strategy and Policy Framework,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 25, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2022/04/us-china-technological-decoupling-a-strategy-and-policy-framework?lang=en.

[8] Vlado Vivoda, “Friend-shoring and Critical Minerals: Exploring the Role of the Minerals Security Partnership,” Energy Research & Social Science 100 (2023): 103085, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103085.

[9] Nayan Seth, “Mine the Tech Gap: Why China’s Rare Earth Dominance Persists,” New Security Beat, August 29, 2024, https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2024/08/mine-the-tech-gap-why-chinas-rare-earth-dominance-persists/., , Accessed January 20, 2025.

[10] June Teufel Dreyer, “China’s Monopoly on Rare Earth Elements—and Why We Should Care,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, October 7, 2020, https://www.fpri.org/article/2020/10/chinas-monopoly-on-rare-earth-elements-and-why-we-should-care/.

[11] Gracelin Baskaran and Meredith Schwartz, “China Imposes Its Most Stringent Critical Minerals Export Restrictions Yet Amidst Escalating U.S.-China Tech War,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, Last modified December 4, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/china-imposes-its-most-stringent-critical-minerals-export-restrictions-yet-amidst.

[12] James Temple, “What China’s Critical Mineral Ban Means for the US,” MIT Technology Review, December 6, 2024, https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/12/06/1108020/what-chinas-critical-mineral-ban-means-for-the-us/.

[13] “Why China’s Critical Mineral Strategy Goes Beyond Geopolitics,” World Economic Forum, November 2024, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/11/china-critical-mineral-strategy-beyond-geopolitics/.

[14] Alexander Korolev and Fengshi Wu, “Australia’s Critical Minerals Strategy amid US–China Geopolitical Rivalry,” Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/australias-critical-minerals-strategy-amid-us-china-geopolitical-rivalry., Accessed January 20, 2025.

[15] David Shepardson, “US Lawmakers Seek to Reduce China’s Dominance of Critical Mineral Supplies,” Reuters, June 18, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/us-lawmakers-seek-address-chinas-dominance-critical-mineral-supply-chains-2024-06-18/.

[16] Meghan L. O’Sullivan and Jason Bordoff, co-chairs, “A Critical Minerals Policy for the United States: The Role of Congress in Scaling Domestic Supply and De-Risking Supply Chains,” Drafted by Robert Johnston with Cina Vazir, Energy & Environment Program, The Aspen Institute, Spring 2023, https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/A-Critical-Minerals-Policy-for-the-United-States-Final-Report.pdf.

[17] Gracelin Baskaran, “Seven Recommendations for the New Administration and Congress: Building U.S. Critical Minerals Security,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 14, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/seven-recommendations-new-administration-and-congress-building-us-critical-minerals.

[18] U.S. Department of Commerce, “A Federal Strategy to Ensure Secure and Reliable Supplies of Critical Minerals,” January 2020, https://www.commerce.gov/sites/default/files/2020-01/Critical_Minerals_Strategy_Final.pdf.

[19] “Smith Applauds President Trump’s Early Action to Protect American Workers and Businesses from Unfair Trade Practices,” United States House Committee on Ways and Means Committee, January 21, 2025, https://waysandmeans.house.gov/2025/01/21/smith-applauds-president-trumps-early-action-to-protect-american-workers-and-businesses-from-unfair-trade-practices/.

[20] Gregory Wischer and Morgan Bazilian, “OPINION: What Could the Trump Administration’s Mineral Policy Look Like?” Benchmark Minerals, https://source.benchmarkminerals.com/article/opinion-what-could-the-trump-administrations-mineral-policy-look-like., Accessed 12 January 2025.

[21] Darla Mercado and Evelyn Cheng, “Trump Says He’s Considering a 10% Tariff on China Beginning as Soon as Feb. 1,” CNBC, January 21, 2025, https://www.cnbc.com/2025/01/21/trump-says-hes-considering-10percent-tariff-on-china-beginning-as-soon-as-feb-1.html.

[22] Erin Hale “As Trump Talks Up Trade War with China, Fears Rise for Rare Earths Supply,” Al Jazeera, January 9, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2025/1/9/as-trump-talks-up-trade-war-with-china-fears-rise-for-rare-earths-supply.

[23] U.S. Department of Energy, “Biden-Harris Administration Invests $17 Million to Strengthen Nation’s Critical Minerals Supply Chain,” U.S. Department of Energy, Last modified December 16, 2024. https://www.energy.gov/articles/biden-harris-administration-invests-17-million-strengthen-nations-critical-minerals-supply.

[24] David Vergun, “Securing Critical Minerals Vital to National Security, Official Says,” U.S. Department of Defense, January 10, 2025, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/4026144/securing-critical-minerals-vital-to-national-security-official-says/.

[25] U.S. Department of Energy, “Critical Minerals and Materials,” U.S. Department of Energy, https://www.energy.gov/topics/critical-minerals-and-materials., Accessed January 20, 2025.

[26] “Export-Import Bank of the United States Board of Directors Approves Supply Chain Resiliency Initiative to Protect U.S. Jobs and Shift Critical Mineral Supply Chains Back to the United States and Away from the People’s Republic of China,” Export-Import Bank of the United States, January 8, 2025, https://www.exim.gov/news/export-import-bank-united-states-board-directors-approves-supply-chain-resiliency.

[27] Robbie Diamond and Morgan Ortagus, “Washington Examiner Op-Ed: The US Must Beat China on Critical Minerals and Advanced Manufacturing,” Secure Energy, November 27, 2024, https://secureenergy.org/op-ed-the-us-must-beat-china-on-critical-minerals-and-advanced-manufacturing/.

[28] Christina Lu, “The Mineral-Rich Want to Get Richer.” Foreign Policy, July 27, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/07/27/critical-mineral-battery-energy-transition-lithium-nickel-chile-indonesia/.

[29] “Assessing Trump’s Critical Minerals Strategy and its Effects (December 2024),” Knightsbridge Strategy Group, https://www.knightsbridgesg.com/post/assessing-trump-s-critical-minerals-strategy-and-its-effects-december-2024. , Accessed January 23, 2025.

[30] Rebecca Harding, “Trump Trade – Back to the Future?,” Flow – Deutsche Bank, November 13, 2024, https://flow.db.com/trade-finance/trump-trade-back-to-the-future.

[31] “As Trump Talks Up Trade War with China, Fears Rise for Rare Earths Supply,” Al Jazeera, January 9, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2025/1/9/as-trump-talks-up-trade-war-with-china-fears-rise-for-rare-earths-supply.

[32] Jay Leary, “China’s Trade Embargo on Critical Minerals to the United States – A Ripple Effect of the New Trump Administration,” Herbert Smith Freehills, December 2024, https://www.herbertsmithfreehills.com/insights/2024-12/chinas-trade-embargo-on-critical-minerals-to-the-united-states., Accessed January 23, 2025.

[33] Melissa B. Mahle, “Critical Minerals: Western-led Efforts to Build Out the Critical Mineral Policy Framework for Secure Supply Chains,” Steptoe, October 31, 2024. https://www.steptoe.com/en/news-publications/stepwise-risk-outlook/critical-minerals-western-led-efforts-to-build-out-the-critical-mineral-policy-framework-for-secure-supply-chains.html.

[34] “As Trump Talks Up Trade War with China, Fears Rise for Rare Earths Supply,” Al Jazeera, January 9, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2025/1/9/as-trump-talks-up-trade-war-with-china-fears-rise-for-rare-earths-supply.

[35] Ling-Tuan Linda Liu, “Taiwan’s Role in the US-China Competition for Critical Minerals,” Wilson Center, September 3, 2024, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/taiwans-role-us-china-competition-critical-minerals., Accessed January 21, 2025.

[36] Bernice Lee, “Why We Need Global Cooperation on Critical Mineral Supplies,” World Economic Forum, December 2023. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/12/why-we-need-global-cooperation-on-critical-mineral-supplies/.

[37] Bernice Lee, “Naïve but Necessary? Cooperation on Critical Mineral Supplies,” Tess Forum, December 5, 2023, https://tessforum.org/latest/na%C3%AFve-but-necessary-cooperation-on-critical-mineral-supplies.