- Introduction

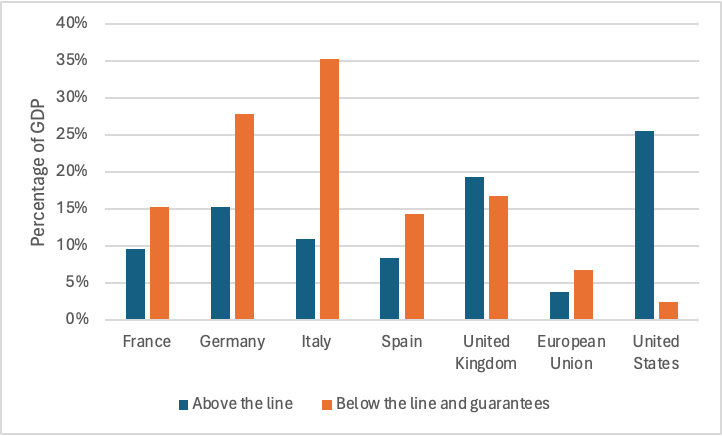

During the COVID-19 crisis in Europe, all EU Member Countries agreed to support the economy to manage the lockdown’s impact and mitigate the detrimental effects of the economic slowdown. The first action by the European Parliament was to activate the general escape rule already included in the Stability and Growth Pact, allowing budgetary measures in the face of exceptional circumstances (European Parliament 2020, 2-6). Solutions adopted worldwide can be classified as above and below-the-line solutions (IMF 2021, 1-16) (figure 1).

Figure 1. Above and below-the-line solutions adopted by countries

Source: IMF data processed by the author

The above-the-line solutions, such as transfers or tax rebates, were primarily used in countries like the US and the UK. In contrast, the leading solutions adopted in Europe were equity injections, direct loans, or loan guarantees. Comparing the role of financial support concerning GDP, some EU countries (like Germany and Italy) invested even more than other countries worldwide (Valla and Miguet 2022, 15).

The EU’s solution for extraordinary public expenditure support affected the sustainability of fiscal policy based on EU regulations. Before the pandemic, the regulatory framework in Europe required member states to maintain a public debt-to-GDP ratio of no more than 60% (or show a significant reduction trend) and a maximum deficit of 3% of GDP. In March 2020, the European Commission temporarily authorized member states to deviate from the Stability and Growth Pact until the pandemic’s effects subsided. Initially, no fixed deadline was provided for this extraordinary measure (Delivorias 2021, 35-36).

This paper analyzes the debt trends during the pandemic period, highlighting the differences in solutions adopted by various EU countries based on official statistics (Section 2). The analysis will consider the economic outlook after the pandemic (Section 3) and the new budgetary constraints approved by the EU (Section 4). The last section will summarize the perspectives of EU countries following the introduction of the new rules (Section 5).

- Debt Trends in the EU During the Pandemic

Public intervention during the pandemic significantly impacted public expenditure and the sustainability of debt in the EU, with the effects being particularly pronounced in certain countries (Table 1).

Table 1. Fiscal Policy in the EU During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic

| Deficit (-) or Surplus (+) / GDP | Debt / GDP | |||||||

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

| Austria | -8.0% | -5.8% | -3.3% | -2.7% | 82.9% | 82.5% | 78.4% | 77.8% |

| Belgium | -9.0% | -5.4% | -3.6% | -4.4% | 111.9% | 107.9% | 104.3% | 105.2% |

| Bulgaria | -3.8% | -3.9% | -2.9% | -1.9% | 24.6% | 23.9% | 22.6% | 23.1% |

| Croatia | -7.2% | -2.5% | 0.1% | -0.7% | 86.1% | 77.5% | 67.8% | 63.0% |

| Cyprus | -5.7% | -1.8% | 2.7% | 3.1% | 114.9% | 99.3% | 85.6% | 77.3% |

| Czechia | -5.8% | -5.1% | -3.2% | -3.7% | 37.7% | 42.0% | 44.2% | 44.0% |

| Denmark | 0.3% | 4.1% | 3.3% | 3.1% | 42.3% | 36.0% | 29.8% | 29.3% |

| Estonia | -5.4% | -2.5% | -1.0% | -3.4% | 18.6% | 17.8% | 18.5% | 19.6% |

| Finland | -5.6% | -2.8% | -0.4% | -2.7% | 74.7% | 72.6% | 73.5% | 75.8% |

| France | -8.9% | -6.6% | -4.8% | -5.5% | 114.9% | 113.0% | 111.9% | 110.6% |

| Germany | -4.3% | -3.6% | -2.5% | -2.5% | 46.1% | 47.3% | 47.0% | 46.1% |

| Greece | -9.8% | -7.0% | -2.5% | -1.6% | 207.0% | 195.0% | 172.7% | 161.9% |

| Hungary | -7.6% | -7.2% | -6.2% | -6.7% | 79.3% | 76.7% | 74.1% | 73.5% |

| Ireland | -5.0% | -1.5% | 1.7% | 1.7% | 58.1% | 54.4% | 44.4% | 43.7% |

| Italy | -9.4% | -8.7% | -8.6% | -7.4% | 155.0% | 147.1% | 140.5% | 137.3% |

| Latvia | -4.4% | -7.2% | -4.6% | -2.2% | 42.7% | 44.4% | 41.8% | 43.6% |

| Lithuania | -6.5% | 1-1% | -0.6% | -0.8% | 46.2% | 43.4% | 38.1% | 38.3% |

| Luxembourg | -3.4% | 0.5% | -0.3% | -1.3% | 24.6% | 24.5% | 24.7% | 25.7% |

| Malta | -9.4% | -7.6% | -5.5% | -4.9% | 52.2% | 53.9% | 51.6% | 50.4% |

| Netherlands | -3.7% | -2.2% | -0.1% | -0.3% | 54.7% | 51.7% | 50.1% | 46.5% |

| Poland | -6.9% | -1.8% | -3.4% | -5.1% | 57.2% | 53.6% | 49.2% | 49.6% |

| Portugal | -5.8% | -2.9% | -0.3% | 1.2% | 134.9% | 124.5% | 112.4% | 99.1% |

| Romania | -9.3% | -7.2% | -6.3% | -6.6% | 46.7% | 48.5% | 47.5% | 48.8% |

| Slovakia | -5.3% | -5.2% | -1.7% | -4.9% | 58.8% | 61.1% | 57.7% | 56.0% |

| Slovenia | -7.6% | -4.6% | -3.0% | -2.5% | 79.6% | 74.4% | 72.5% | 69.2% |

| Spain | -10.1% | -6.7% | -4.7% | -3.6% | 120.3% | 116.8% | 111.6% | 107.7% |

| Sweden | -2.8% | 0.0% | 1.2% | -0.6% | 40.2% | 36.7% | 33.2% | 31.2% |

| EU 27 | -6.7% | -4.7% | -3.4% | -3.5% | 90.0% | 87.4% | 83.4% | 81.7% |

Source: Eurostat data processed by the author

Among the EU’s 27 countries, the first year of the pandemic saw a massive increase in the deficit-to-GDP ratio (averaging -6.7% in 2020) and the debt-to-GDP ratio (averaging 90% in 2020). By 2023, these values became more sustainable, with the deficit-to-GDP ratio almost halved (-3.5%) and the debt-to-GDP ratio decreasing by 8%.

A country-by-country analysis reveals that in 2020, Spain (-10.1%), Greece (-9.8%), Italy (-9.4%), and Romania (-9.3%) experienced the most significant impacts on the deficit-to-GDP ratio. Only Denmark and Sweden managed to maintain a ratio lower than -3%. By 2023, the situation improved significantly, with Cyprus, Portugal, Ireland, and Denmark achieving a surplus, and only ten countries failing to meet the -3% threshold.

Examining the debt stock as a percentage of GDP, there was a substantial increase in 2020, with Belgium, Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, and Portugal exceeding a 100% ratio. By 2023, all countries saw a notable decrease in their debt-to-GDP ratios, with only Belgium, Italy, Greece, and Spain remaining slightly above 100%.

- Economic Forecast in the EU

Economic forecasts for the EU countries for the coming years highlight significant changes in key macroeconomic variables, such as GDP growth and inflation rates (Table 2).

Table 2. Forecast for Macroeconomic Variables in EU Countries

| GDP growth | Inflation rate | |||||

| 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

| Austria | -0.7% | 0.6% | 1.4% | 7.7% | 4.0% | 3.0% |

| Belgium | 1.5% | 1.4% | 1.5% | 2.3% | 3.5% | 2.3% |

| Bulgaria | 2.0% | 1.9% | 2.5% | 8.6% | 3.4% | 2.9% |

| Croatia | -0.4% | 1.1% | 2.8% | 12.0% | 2.9% | 2.3% |

| Cyprus | 2.4% | 2.8% | 3.0% | 3.9% | 2.4% | 2.1% |

| Czechia | -0.4% | 1.1% | 2.8% | 12.0% | 2.9% | 2.3% |

| Denmark | 0.5% | 0.9% | 1.6% | 3.4% | 1.7% | 2.0% |

| Estonia | -3.5% | 0.6% | 3.2% | 3.4% | 3.2% | 2.1% |

| Finland | -0.4% | 0.6% | 1.6% | 4.3% | 1.4% | 1.5% |

| France | 0.9% | 0.9% | 1.3% | 5.7% | 2.8% | 2.0% |

| Germany | -0.3% | 0.3% | 1.2% | 6.0% | 2.8% | 2.4% |

| Greece | 2.2% | 2.3% | 2.3% | 4.2% | 2.7% | 2.0% |

| Hungary | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.8% | 8.4% | 2.5% | 2.0% |

| Ireland | -1.9% | 1.2% | 3.2% | 5.2% | 2.2% | 1.9% |

| Italy | 0.6% | 0.7% | 1.2% | 5.9% | 2.0% | 2.3% |

| Latvia | -0.3% | 2.1% | 3.0% | 8.7% | 2.4% | 2.4% |

| Lithuania | -0.6% | 1.7% | 2.7% | 9.1% | 2.2% | 2.2% |

| Luxembourg | -0.8% | 1.3% | 2.1% | 2.9% | 2.6% | 2.3% |

| Malta | 6.1% | 4.6% | 4.3% | 5.6% | 2.9% | 2.7% |

| Netherlands | 0.2% | 0.4% | 1.6% | 4.1% | 2.6% | 2.0% |

| Poland | 0.2% | 2.7% | 3.2% | 10.9% | 5.2% | 4.7% |

| Portugal | 2.3% | 1.2% | 1.8% | 5.3% | 2.3% | 1.9% |

| Romania | 1.8% | 2.9% | 3.2% | 9.7% | 5.8% | 3.6% |

| Slovakia | 1.1% | 2.3% | 2.6% | 11.0% | 3.5% | 2.6% |

| Slovenia | 1.3% | 1.9% | 2.7% | 7.2% | 2.9% | 2.0% |

| Spain | 2.5% | 1.7% | 2.0% | 3.4% | 3.2% | 2.1% |

| Sweden | -0.1% | 0.2% | 1.6% | 5.9% | 1.7% | 1.9% |

| EU 27 | 0.5% | 0.9% | 1.7% | 6.3% | 3.0% | 2.5% |

Source: European Commission (2024)

The last year (2023) was still challenging for EU countries due to low GDP growth (averaging 0.5%) and high inflation rates (6.3%). Eleven of the twenty-three countries recorded negative yearly GDP growth, while only Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, Malta, Portugal, and Spain experienced growth of at least 2%. The inflation rate was particularly high in countries like Croatia, Czechia, Poland, and Slovakia, where it reached double digits in 2023.

The forecasts for the next two years are more optimistic regarding economic growth and inflation reduction. By 2025, the average economic growth is projected to be 1.7%, with 18 countries expected to surpass the EU27 average. The inflation rate is also expected to decrease significantly, nearing the European Central Bank’s 2% target (European Parliament 2024b, 1-3). Finland, Ireland, Portugal, and Sweden are anticipated to achieve inflation rates even lower than the Central Bank’s target.

- New Budgetary Plans for Euro Area Member States

The COVID-19 crisis exposed several limitations in the current fiscal regulations within the EU. European regulatory authorities began discussing revisions to the regulatory framework, highlighting the disparities in economic fundamentals across Europe, limited resilience to shocks for some EU members, the lack of pro-cyclical fiscal policy instruments, and the spillover effects of a single-country crisis (European Parliament 2023, 5).

On April 26, 2023, the European Commission presented the EU Economic Governance Reform, aiming to approve the new framework by the end of 2023. The new safeguard measures include (European Parliament 2024a, 10):

- Country-specific fiscal adjustments;

- Medium-term focus;

- More observable indicators;

- A deficit resilience safeguard;

- Automatic debt-based excessive deficit procedures;

- Additional safeguards.

The country-specific constraints require a minimum annual average reduction in the projected general government debt-to-GDP ratio by 1% for Member States with public debt above 90% of their GDP and by 0.5% for those with ratios between 60% and 90%.

The focus will be on medium- to long-term forecasts, with each state required to construct its trajectory over four years (with an additional three years allowed for a more gradual debt reduction if needed). Compliance will be monitored solely through net public expenditure targets. The Commission will establish a control account to track cumulative deviations from the expenditure path, and Member States will be required to report annually on their plans.

The degree of debt challenge for a Member State will become a crucial factor in assessing whether to initiate an Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP). The approach based on simple and measurable indexes will facilitate monitoring and create objective paths for the fiscal policies of member countries.

The deficit resilience safeguard ensures continued fiscal adjustment by establishing a “common resilience margin” relative to the 3% deficit-to-GDP reference value. The margin size depends on the debt level: it is set at 1.5% for Member States with debt-to-GDP ratios above 90% and at least 1% for all other countries. Furthermore, it requires an annual improvement in the structural primary balance of 0.3% of GDP to achieve the margin, potentially reducing to 0.2% if the adjustment period is extended.

Deviations from the net expenditure path of 0.5% of GDP annually or 0.75% on a cumulative basis should prompt the Commission to issue a report under a debt-based Excessive Deficit Procedure.

The European Commission and the European Council approved the new political agreement on February 10, 2024. The implementation results of the new rule may vary from country to country, with notable differences observable among the founding countries of the European Union (excluding the UK) (Table 3).

Table 3. Economic Fundamentals for a Selection of EU Countries

| Household debt / GDP | Employement rate | Business confidence | Bankruptcy incidence in Europe | Home ownership rate | |

| Belgium | 58.5% | 66.9% | -11 | 2.6% | 72.1% |

| Denmark | 85.6% | 70.0% | -4 | 1.2% | 60.0% |

| France | 63.9% | 68.8% | 99.2 | 15.1% | 63.4% |

| Germany | 52.8% | 77.5% | 89.3 | 5.1% | 47.8% |

| Greece | 42.6% | 89.1% | 111 | n.a. | 69.6% |

| Ireland | 25.9% | 74.0% | n.a. | n.a. | 70.4% |

| Italy | 39.0% | 62.1% | 88.4 | 5.7% | 74.3% |

| Luxembourg | 68.2% | 69.1% | 97.1 | 2.7% | 72.4% |

| Netherlands | 88.8% | 82.5% | -2.8 | 1.2% | 70.6% |

| Portugal | 56.0% | 56.9% | 1.9 | n.a. | 77.8% |

| Spain | 48.0% | 51.4% | -6.3 | 5.2% | 75.3% |

Source: Trading Economics data processed by the author

The analysis of private debt across different countries reveals differences among the founding members of the EU. Countries with lower private debt-to-GDP ratios, such as Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain, tend to provide more public services to citizens. Therefore, a significant reduction in public debt at the government level may be more detrimental to the citizens of these countries.

On average, the employment rate in European countries is relatively high compared to other regions. However, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and France face significant unemployment issues. The new fiscal policies may negatively impact the public support available to unemployed citizens in these countries.

At the end of the pandemic period, some economies still struggle with growth problems in the private sector, particularly in Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Spain. Larger economies like France, Germany, and Italy also experience a high incidence of bankruptcies. For all these countries, new public budget constraints may limit opportunities to support the economy and prevent bankruptcies, potentially worsening their economic outlook in the short term.

Homeownership rates are highest in Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, and Spain, as housing is a primary investment for many families. Investing in real assets is often seen as a safe strategy in a down-market scenario, which may have helped citizens in these countries suffer fewer losses during the pandemic. Consequently, these countries may be more aggressive in reducing public expenditure, as citizens may have more resources to manage a few years of public budget cuts if necessary.

- Perspectives for the EU Area After the Introduction of the New Budgetary Constraints

The economic forecast for the EU countries indicates substantial growth opportunities driven by public expenditure, private consumption, and export growth. Labor market projections suggest an increase in employment and a decrease in the unemployment rate (OECD 2024, 101-104).

Additionally, the forecast for the EU area predicts a decrease in the inflation rate in the coming months, which will enable the European Central Bank (ECB) to reduce interest rates. Current inflation data increase the likelihood of an interest rate reduction to 4.12% by the end of 2024 and to 2.75% by 2026 (European Central Bank 2024, 18). The ECB announced the first interest rate revision on June 6, with a 0.25% reduction in all reference interest rates starting June 12.

However, rating agencies have noted significant issues for European countries, which are still rated as investment grade (Table 4).

Table 4. Ratings of EU Countries

| S&P | Moody’s | Fitch | |

| Austria | AA+ | Aa1 | AA+ |

| Belgium | AA | Aa3 | AA- |

| Bulgaria | BBB | Baa1 | BBB |

| Croatia | BBB+ | Baa2 | BBB+ |

| Cyprus | BBB | Baa2 | BBB |

| Czechia | AA- | Aa3 | AA- |

| Denmark | AAA | Aaa | AAA |

| Estonia | AA- | A1 | A+ |

| Finland | AA+ | Aa1 | AA+ |

| France | AA | Aa2 | AA- |

| Germany | AAA | Aaa | AAA |

| Greece | BBB- | Ba1 | BBB- |

| Hungary | BBB- | Baa2 | BBB |

| Ireland | AA | Aa3 | AA- |

| Italy | BBB | Baa3 | BBB |

| Latvia | A+ | A3 | A- |

| Lithuania | A+ | A2 | A |

| Luxembourg | AAA | Aaa | AAA |

| Malta | A- | A2 | A+ |

| Netherlands | AAA | Aaa | AAA |

| Poland | A- | A2 | A- |

| Portugal | A- | A3 | A- |

| Romania | BBB- | Baa3 | BBB- |

| Slovakia | A+ | A2 | A- |

| Slovenia | AA- | A3 | A |

| Spain | A | Baa1 | A- |

| Sweden | AAA | Aaa | AAA |

| European Union | AA | Aaa | AAA |

Source: S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch ratings data processed by the author

Countries considered less financially stable include Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Italy, Greece, Hungary, and Romania, which have not faced downgrades or negative outlooks in the past year. Compared to previous crises, such as the Great Financial Crisis, market perceptions of the region’s risk are relatively positive. No country has received the negative valuations observed during the Euro-Debt crisis (e.g., Baum, Schafer, and Stephan 2016, 120-121).

EU markets have seen a reduction in sovereign bond yields across maturities, with spreads relative to the German Bund also decreasing in line with lowered inflation expectations (European Parliament 2024a, 3). In a growing economy, the anticipated reduction in the cost of debt for EU countries will help lower the deficit-to-GDP ratio. Some countries, like Belgium, with the “Peteghem Bond,” which utilizes high-yield government bonds to reduce the interest rate margin of banks, will achieve faster reductions in their deficit-to-GDP ratios.

One of the critical challenges in the coming years will be adapting the green and digital transition strategies, supported by the Next Generation EU and national recovery plans, to the new budgetary constraints emerging after the reintroduction of EU financial controls (European Parliament 2024a, 4-7). Many member countries have struggled to achieve the goals of digitalization and green development. New regulations, such as the European Building Efficiency Directive, have been established to set new deadlines and targets. In the medium to long term, the impact of the twin transition will benefit all of Europe, though it may pose additional constraints to manage, particularly in the context of the Ukraine and Israel conflicts (Celeste and Dominioni 2023, 11-15).

Countries that have used tax credits to support the green and digital transition, like Italy, are more vulnerable to the new fiscal policies to be adopted in the coming years. The tax deduction opportunities already offered to citizens (such as the 110% tax credit for building efficiency) will reduce tax inflows for the next ten years.

The reintroduction of fiscal rules in Europe may face initial difficulties, and it may sometimes be necessary to adopt excessive deficit procedures for certain countries. Even if some member states cannot fully adhere to the guidelines, the overall system will remain stable, as the European Parliament and the European Commission have experience in managing such events (Wijffelaars, Koopman, van Harn 2024, 7-8) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Compliance to Deficit and debt rule in the European Union

Source: European Commission data processed by the author

Over the past twenty years, no member state has achieved full compliance with EU fiscal rules, with the primary issues related to the debt rule. Due to the high initial levels of debt in some countries, meeting this requirement remains challenging.

The economic forecast for implementing the new fiscal policy is heavily influenced by the international scenario and the risks associated with wars and conflicts. The Russia-Ukraine war is not expected to end in the short term, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict remains ongoing. In such a context, international trade volumes may be affected, impacting European countries engaged in global exports and imports. Fiscal policy constraints may continue to be influenced by these international dynamics, and a critical issue for the sustainability of the new policy is reducing dependence on energy production from conflict-exposed countries. Currently, EU member states remain dependent on foreign energy supplies, and any further increase in energy costs could negatively impact the inflation targets set by the ECB and the fiscal budget constraints imposed by the European Commission.

References

- Baum, Christopher F., Dorothea Schäfer, and Andreas Stephan. 2016. “Credit Rating Agency Downgrades and the Eurozone Sovereign Debt Crises.” *Journal of Financial Stability* 24: 117-131.

- Celeste, Edoardo, and Goran Dominioni. 2023. “Digital and Green: Reconciling the EU Twin Transitions in Times of War and Energy Crisis.” REBUILD Centre working paper no. 11.

- Delivorias, Angelos. 2021. “Introduction to the Fiscal Framework of the EU: The Maastricht Treaty, the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance, and the Stability and Growth Pact.” Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.europarl.europa.eu.

- European Central Bank. 2024. “The ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters.” Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.ecb.europa.eu.

- European Commission. 2024. “European Economic Forecast.” Accessed May 19, 2024. https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu.

- European Parliament. 2020. “The ‘General Escape Clause’ within the Stability and Growth Pact.” Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.europarl.europa.eu.

- ———. 2023. “Enhanced Political Ownership and Transparency of the EU Economic Governance Framework.” Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.europarl.europa.eu.

- ———. 2024a. “Implementation of the Stability and Growth Pact under Exceptional Times.” Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.europarl.europa.eu.

- ———. 2024b. “EU Economic Developments and Projections.” Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.europarl.europa.eu.

- International Monetary Fund. 2021. “Fiscal Monitor, October 2021: Strengthening the Credibility of Public Finances.” Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.imf.org.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2024. *OECD Economic Outlook – May 2024*. Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.oecd-library.org.

- Valla, Natacha, and Francois Miguet. 2022. “How Have Major Economies Responded to the COVID-19 Pandemic?” Economic Governance Support Unit. Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.europarl.europa.eu.

- Wijffelaars, Maartje, Stefan Koopman, and Earik-Jan van Harn. 2024. “Are the New EU Budget Rules Fit for Long-Term Challenges and Ambitions?” Rabobank Research. Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.rabobank.com.