With ongoing geopolitical risks affecting global supply chains and market stability, energy security has become a central concern for nations worldwide in their policy considerations. Energy demands are increasing, and the supply of essential resources, including oil, natural gas, and electricity, is facing new threats as the world continues to recover from the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. The fundamental concept of energy security is the consistent availability of energy in a variety of forms, at a reasonable price, and in sufficient quantities.1 This concept is crucial for maintaining economic stability, national security, and social welfare. Supply disruptions can have a significant impact on countries that depend on imports, regardless of whether they are the result of natural disasters, geopolitical risks, or technical deficiencies.

The conflict between Russia and Ukraine, which started in February 2022, has developed beyond conventional warfare. The conflict had led to military and economic repercussions across Europe, affecting regional energy stability. A European energy crisis, particularly in the Baltic states, continues to affect markets because of sanctions against Russia and the disruption of Ukrainian energy infrastructure.2 In attempts to diversify energy sources, these nations have invested in reducing their dependence on Russia by establishing alternative trade routes while investing in renewable energy infrastructure.

Conversely, the ongoing tensions between Iran and Israel, influenced by proxy conflicts and nuclear-related issues, also pose significant challenges to regional energy security. Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are notably affected by these confrontations, which have substantial implications for regional energy security. Iran’s strategic influence over the Straits of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandab, through which a significant portion of the global oil supply flow, enables it to pose a threat to the global energy trade.

The broader issue of energy security is underscored by both conflicts, which demonstrate the significant impact of political instability on global supply chains and energy access. The Iran-Israel conflict introduces potential risks in jeopardizing crucial oil transit routes, while the Russia-Ukraine War has caused immediate energy shortages and shifted the focus of European energy policy toward diversification. These conflicts highlight the economic and political challenges associated with energy security, illustrating how political instability can impact global supply chains and access to energy resources. This article examines the key dimensions of the Russia-Ukraine War and the Iran-Israel conflict, analyzing their direct impacts on regional energy security, the geoeconomic shifts they have influenced, and resulting market volatility. The analysis further aims to assess the immediate and long-term implications of both conflicts on the energy sector and their impact on energy stability by contrasting their effects.

Key Developments

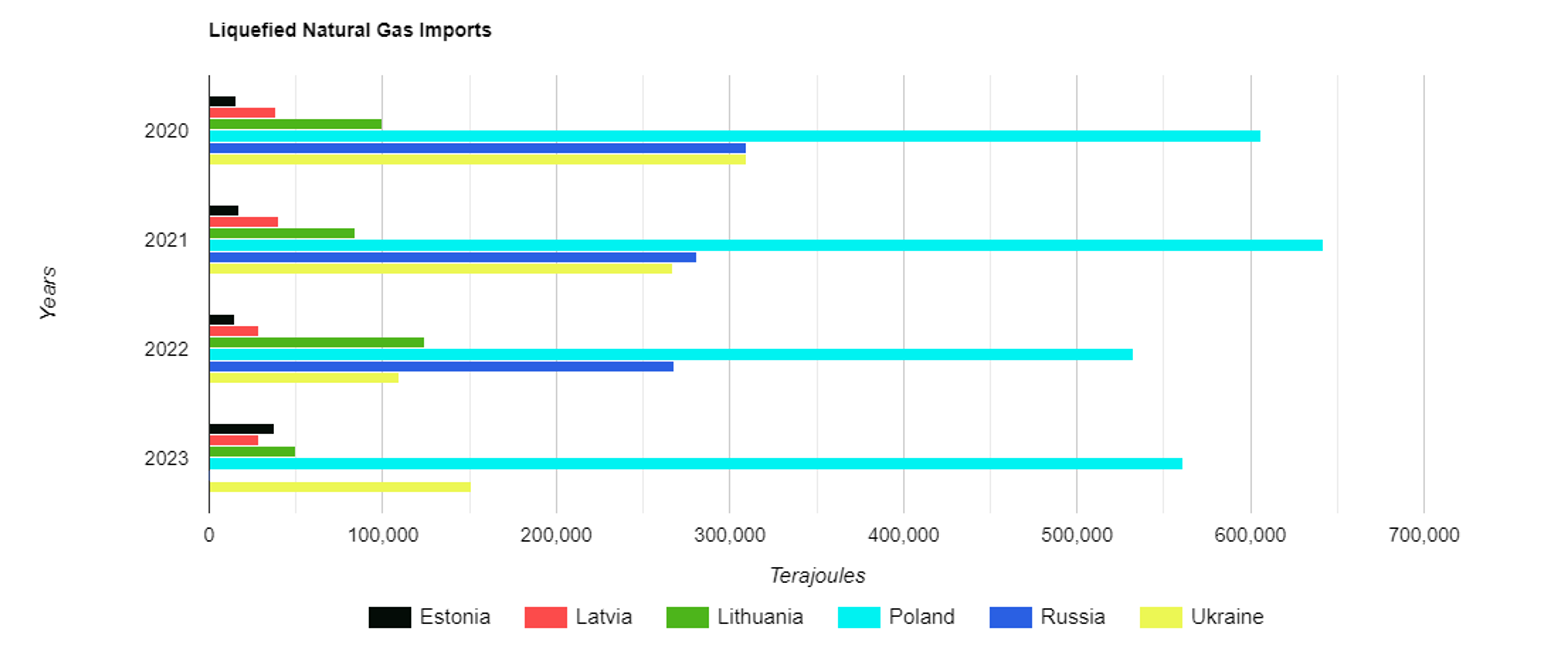

The Russia-Ukraine conflict has notably influenced energy trade dynamics, especially for countries in the Baltic region, along with Poland, Ukraine, and Russia. The ongoing conflict, along with associated sanctions on Russia, has led to significant shifts in energy supply chains and price volatility. The Baltic states have taken substantial steps to reduce their reliance on Russian energy, primarily in the natural gas and oil sectors. In 2022, Lithuania became the first EU country to completely stop Russian gas imports, largely facilitated by the Klaipėda liquified natural gas (LNG) terminal.3 Estonia is set to complete its LNG terminal project in Paldiski to secure alternate supplies by late 2022.4 Poland, previously a major importer of Russian energy, has made significant moves toward energy diversification. In 2022, Poland stopped purchasing Russian gas after 31 years of dependence by ending the Yamal contract, opting instead to import LNG from Qatar and the United States (U.S.).5 Poland’s Świnoujście LNG terminal has been critical in meeting the country’s demand, with LNG imports increasing by approximately 60% between 2022 and 2023.6 As of 2023, the Baltic region had reduced its reliance on Russian gas by over 80%, primarily replacing it with global LNG sources, highlighting a significant transition in energy strategies.7

Figure 1: Imports of Natural Gas in Russia, Ukraine, and the Baltics

Source: Author’s creation adapting data from IEA, Kyiv Post and using imageonline.co

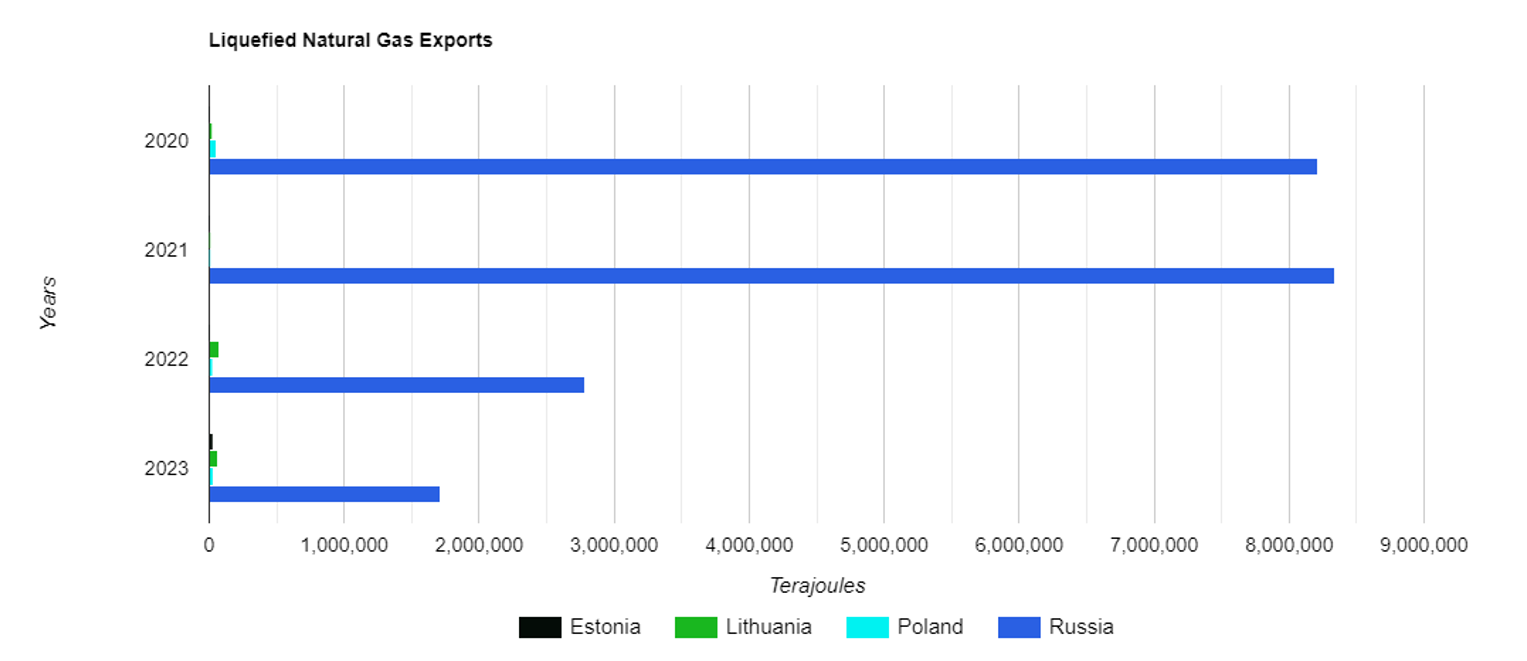

Figure 2: Exports of Natural Gas from Russia and the Baltics

Source: Author’s creation adapting data from IEA, Interfax and using imageonline.co

Poland’s natural gas imports from Russia fell to near zero by 2023, replaced by supplies from the newly completed Baltic Pipe, which imports natural gas from Norwegian fields.8 The country’s oil imports from Russia also declined by about 70% in 2023, with Saudi Arabia emerging as a major alternative supplier.9 Ukraine, which stopped importing Russian gas back in 2015, has further enhanced its energy independence since the war in 2022. By 2023, Ukraine had significantly boosted its domestic natural gas production by approximately 5% while importing gas primarily from European neighbors, including Slovakia and Poland.10 Despite significant infrastructure damage from Russian attacks, Ukraine managed to secure electricity imports from the EU, which have increased by 15% by 2024 to mitigate the impact of power shortages.11 In the oil sector, Ukraine’s imports have increasingly come from the EU, as Russian supplies were halted entirely due to the conflict and sanctions. Oil imports from Russia to Baltic states were also drastically cut following EU sanctions in 2022.

EU sanctions have resulted in a significant shift in the direction of Russia’s energy exports. Russia’s pipeline gas exports to the EU, which had been its primary market, experienced a decline of over 82% between 2023 and 2024.12 Nevertheless, Russia’s LNG exports to Europe experienced an increase during the same period. This difference arises from the flexibility of LNG, which can be rerouted globally, allowing Russia to maintain a foothold in European markets despite sanctions targeting pipeline supplies. Russia adjusted to restrictions on pipeline gas by increasing LNG exports, which allowed continued access to European markets despite the sanctions. Furthermore, Russia redirected its pipeline gas exports to Asian markets, notably China, via the Power of Siberia pipeline to provide further incentives to non-Western markets.13

The Iran-Israel conflict has significantly influenced energy imports and exports across key countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), including Jordan, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. Iran continues to play a substantial role as a regional oil producer, despite sanctions that restrict its access to certain export markets. Within the first 10 months of 2023, Iran’s oil exports totaled around 1.1 million barrels per day (bpd) to China.14 In 2023, sanctions enforcement softened, allowing Iran to increase exports. Natural gas exports, primarily to Iraq and Turkey, have remained steady, with about 16.5 billion cubic meters (bcm) exported annually.15 The development of Iran’s South Pars field has promoted its role as a key player in regional gas supply despite domestic challenges.

Israel’s natural gas sector, especially from its offshore fields (Leviathan and Tamar), has grown rapidly since 2020. Israel became a natural gas exporter, supplying Egypt and Jordan with significant volumes of natural gas. In 2023, gas exports to Egypt were estimated at 2.5 bcm annually, facilitating Egypt’s role as a regional hub for LNG exports, especially since it owns the only gas liquefaction plant in the Eastern Mediterranean.16 In addition to energy cooperation in the MENA region, Israel’s energy independence, particularly in natural gas, has decreased its need for imports, strengthening its position within the region. Jordan has minimal energy reserves and heavily relies on imports to meet its energy demands. Its energy mix includes natural gas imports from Israel (via the Leviathan field), which have helped reduce the country’s energy costs. In 2022, Israel provided Jordan with 2.9 bcm, a potential alternative as the country seeks to diversify away from more expensive energy imports.17 Additionally, Jordan imports oil from Iraq, which accounted for about 5 million barrels annually by 2023.18 However, Jordan faces challenges in energy security due to its reliance on external suppliers, despite efforts to diversify sources, including imports from Israel and Iraq.

The UAE, a key producer in the region, maintained an average export level of 3.2 million bpd in 2023.19 Natural gas exports, particularly through LNG, also increased, though at a smaller scale. At the same time, Saudi Arabia remains a central player in the energy market. The kingdom possesses up to 17% of the world’s petroleum reserves and exports around 12.7 million bpd of oil.20 The kingdom has also been focusing on increasing its natural gas production to meet domestic electricity generation needs, reducing its reliance on oil for power.

Egypt has positioned itself as a regional energy hub, benefiting from the imports of Israeli natural gas, which it processes and re-exports as LNG. In 2023, Egypt’s LNG exports, reaching around 8.9 bcm by 2023, primarily served European markets, a trend that has been rising since 2020 amidst global supply chain disruptions. In addition to re-exports, Egypt has been working on boosting its domestic energy production, especially through its Zohr gas field. In 2024, the field was contributing significantly to both domestic energy consumption and export capabilities. Nevertheless, Zohr’s production levels have been decreasing, from a high of 3.2 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d) in 2019 to 1.9 bcf/d in early 2024.22 Egypt is at risk of reverting to a net gas importer if this decline persists. The decrease in output has been partly attributed to limited foreign investment, a situation impacted by Egypt’s debt levels. To address this issue, Egypt intends to increase pipeline imports from Israel and Cyprus and construct new wells at Zohr beginning in 2025 to maintain its export potential.

Russia-Ukraine War: Energy Dependence or Independence?

The war between Russia and Ukraine has to some extent altered the energy agenda across Eastern Europe. The Baltics and Ukraine, along with Russia, have faced distinct challenges in managing the disruption of energy supplies as well as finding alternative solutions to mitigate their dependence on Russian energy. The ongoing conflict has intensified the strategic importance of energy, creating significant geopolitical and economic consequences for the region. Countries with varying levels of reliance on Russian oil, gas, and electricity have reassessed their energy policies, accelerated diversification strategies, and strengthened infrastructure in response to the crisis. Russia has also been affected, as it has had to redirect its energy exports due to sanctions and the loss of its market share in Europe.

Lithuania has taken notable steps to reduce its reliance on Russian energy. Prior to the war, Lithuania was highly dependent on Russian electricity, but it had already begun taking steps to decouple from Russian energy sources. By 2022, Lithuania had fully disconnected from Russian electricity imports and integrated into the EU power grid, a significant move that has shielded the country from the disruptions caused by the war.23 Additionally, Lithuania’s LNG terminal in Klaipėda has played a critical role in ensuring its energy security. The terminal, which became operational in 2014, can handle up to 3.75 bcm of natural gas annually, more than enough to cover Lithuania’s entire gas demand.24 This has allowed the country to completely replace its reliance on Russian natural gas. This shift highlights Lithuania’s early initiatives to develop a resilient energy infrastructure, enabling it to better manage disruptions compared to some neighboring countries.

Latvia was similarly dependent on Russian natural gas before the war; however, the war has led Latvia to intensify its shift toward alternative energy sources. One of Latvia’s key energy assets is the Inčukalns underground gas storage facility, which has a capacity of 2.3 bcm.25 This facility has been crucial in helping Latvia manage its gas supply since the war began. By the end of 2023, Latvia had outlawed Russian gas imports, with much of the replacement coming from LNG sourced through European networks.26 Latvia has also begun to increase its investment in renewable energy sources, particularly wind and solar power, to further diversify its energy mix. This transition has been facilitated by Latvia’s integration into the EU energy market, which has allowed it to import more electricity from neighboring EU countries as it reduces its reliance on Russia. Latvia has received emergency support from the EU to address energy shortages during the winter months, illustrating the role of regional cooperation in energy security.

Estonia, much like its Baltic neighbors, has made significant strides in reducing its dependence on Russian energy. Before the war, Estonia relied on Russia for around 40% of its electricity imports.27 However, since the conflict began, Estonia has increased efforts to enhance domestic energy production and reduce its reliance on imports from Russia. A key aspect of Estonia’s strategy has been its focus on renewable energy, particularly wind power. This shift aligns with Estonia’s efforts to meet climate goals under the European Green Deal are contributing to its overall energy transition.29 In efforts to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 and create a more sustainable economy, the European Green Deal involves making sure that all EU member states are fairly and inclusively included in the shift to a greener future, which includes lowering emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG), increasing the use of clean energy, and encouraging a circular economy. By 2023, renewable energy accounted for over 30% of Estonia’s electricity generation.28 Estonia’s wind energy capacity has expanded significantly, with new projects coming online to help fill the gap left by the reduction in Russian energy imports. Additionally, Estonia has improved its interconnections with Finland and other European countries, further reducing its vulnerability to energy disruptions. Estonia’s government has also been working on policies to encourage energy efficiency and reduce overall energy consumption, which has helped the country manage its energy needs during the war-induced crisis.

Ukraine has faced the most severe energy security challenges due to the direct impact of the war on its infrastructure. Since the conflict began, Russia has targeted Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, resulting in widespread damage to power plants, transmission lines, and gas pipelines. Despite significant challenges, Ukraine has maintained some energy security through European imports. Additionally, Ukraine has been importing natural gas from Europe through reverse flow mechanisms, which have allowed it to replace some of the gas that would have otherwise come from Russia. Ongoing Russian attacks have resulted in substantial damage to Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, which has been significantly affected by the conflict. Approximately 73% of its thermal power facilities are currently inoperative as of mid-2024.30 This has resulted in blackouts, with some regions experiencing outages for 12 hours or more each day. By importing electricity from Europe, Ukraine has been able to maintain a portion of its energy supply, despite the challenges it faces. During critical periods, cross-border trade capacity has reached up to 2 GW.31 However, the attacks have caused a US$10 billion toll on the energy sector, which includes damages to power plants, gas pipelines, and heating systems.32 Ukraine’s ability to secure alternative energy sources has been essential in sustaining its energy system under challenging conditions.

The conflict has notably impacted Russia’s energy export market. Western sanctions and the EU’s efforts to reduce its dependence on Russian energy have affected Russia’s access to the European market. In response, Russia has redirected much of its oil and gas exports to Asia. This redirection has helped Russia mitigate some of the economic impacts of sanctions, although it has not fully compensated for the loss of its European customers. Additionally, Russia’s energy sector has encountered challenges in sustaining production levels, partly due to limited access to new technology and foreign investment, which has been critical in sustaining its oil and gas fields. Over time, this could reduce Russia’s ability to remain a dominant energy supplier, particularly if the war continues and sanctions remain in place.

Energy security in Eastern Europe is still being impacted by the war, and the transition to energy independence remains on the EU energy agenda. Nevertheless, several countries have had to rapidly adapt to the new geopolitical reality, with Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia making significant strides in reducing their dependence on Russian energy. Ukraine, despite being the most severely affected, has shown remarkable resilience by securing alternative energy imports and managing its energy needs in the face of widespread infrastructure damage. Meanwhile, Russia has had to redirect its energy exports to new markets in Asia, as sanctions and the loss of its European customers have reshaped its role in the global energy market. These developments highlight the importance of energy diversification, regional cooperation, and resilience-building efforts to address the challenges posed by geopolitical crises.

Iran-Israel Conflict: Forging New Transit Routes

The Iran-Israel conflict has contributed to regional energy challenges, affecting countries such as Egypt, Jordan, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia in different ways. In Egypt, the conflict has heightened the importance of securing its oil and gas export routes, particularly through the Suez Canal and SUMED pipeline, which are critical global energy transit points. Egypt’s growing role as a natural gas exporter, especially through LNG, has made it a key player in the Mediterranean energy landscape. However, potential escalations in the Iran-Israel conflict present risks to maritime security in the Red Sea and Bab al-Mandab Strait, with possible implications for Egyptian energy exports and global oil flows. Israel has enhanced its energy security in recent years, partly due to the development of the Leviathan and Tomar gas fields in the Mediterranean. These fields have made Israel a net exporter of natural gas, with exports to Jordan and Egypt, as well as plans to supply Europe through LNG facilities in Egypt.

In 2022, Israel exported over 10 bcm of natural gas, positioning itself as an emerging energy power in the region.33 However, the ongoing tensions with Iran, particularly in areas like Syria and Lebanon, create risks for Israeli energy infrastructure, including offshore gas platforms, which remain exposed to potential threats. Iran is a significant player in regional energy security dynamics due to its substantial oil reserves and its strategic location along the Strait of Hormuz, through which approximately 20% of the world’s oil supply passes.34 The potential for disruptions in the Strait of Hormuz amid regional tensions remains a key concern for global energy security, as any closure of the strait could send global oil prices skyrocketing.

In recent years, maritime security in the Bab al-Mandab Strait has been affected by attacks, including those attributed to Houthi militants in Yemen. These attacks have resulted in substantial disruptions to regional maritime traffic by targeting oil tankers and shipping vessels. These attacks have impacted Israel’s maritime traffic to the Eilat port on the Red Sea, affecting critical transport lanes. Israel’s energy imports and exports were particularly affected by the near halt of shipping to Eilat, as the port is a critical access point to both the Red Sea and global markets.35 The escalation of Houthi attacks through the Bab al-Mandeb poses an additional danger to maritime shipping, which could potentially affect global energy security by obstructing critical shipping routes for oil and gas.36

Jordan, which is highly dependent on energy imports, particularly from neighboring countries like Israel, has benefited from the Israel-Jordan gas deal, which can supply Jordan with around 12 bcm of natural gas annually from Israel’s Leviathan field.37 This arrangement has strengthened Jordan’s energy security; however, regional instability stemming from the Iran-Israel conflict poses potential risks to energy cooperation. Jordan’s reliance on imported energy, particularly natural gas, makes it vulnerable to any regional conflict that could affect supply routes or infrastructure.

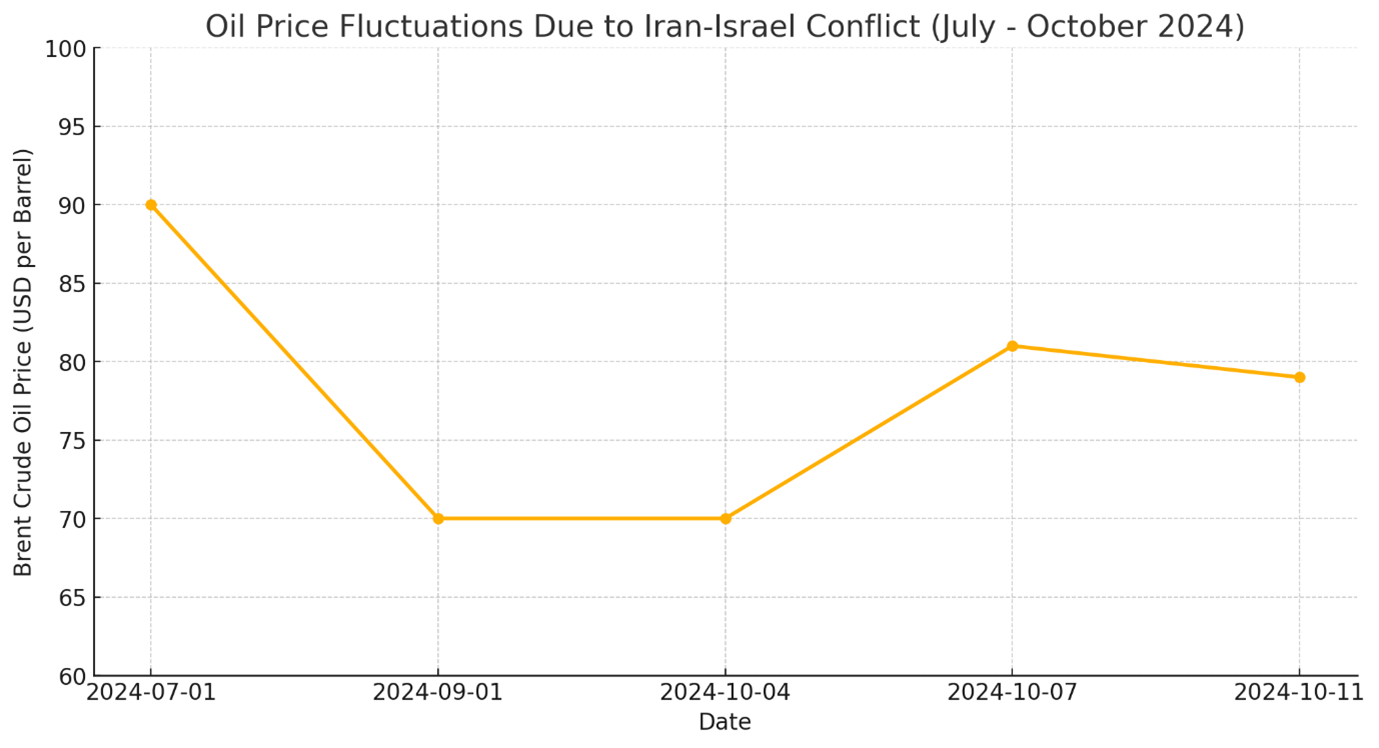

Figure 3: Oil Fluctuations

Source: Author’s creation, adapting data from The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/11/business/oil-prices-iran-israel.html.

As a major oil producer and exporter, the UAE faces notable energy security challenges in light of regional tensions, including the Iran-Israel conflict. The UAE exports approximately 4 million bpd of crude oil, much of it passing through the Strait of Hormuz, making it highly vulnerable to any Iranian military activity or threats in the area.38 In recent years, the UAE has invested heavily in diversifying its export routes to mitigate this risk, including the development of the Habshan-Fujairah pipeline, which bypasses the Bab al-Mandab and Hormuz straits and can transport up to 1.5 million bpd.39 Additionally, the UAE has been expanding its renewable energy capacity, aiming to triple the share by investing between AED150 and AED200 billion in cleaner sources by 2030, part of a broader strategy to reduce its reliance on oil exports and to support its long-term energy security.40 Saudi Arabia, the largest oil producer in the region, with production levels around 11 million bpd, faces similar vulnerabilities due to its reliance on the Strait of Hormuz for oil exports.41 Saudi Arabia has implemented measures to diversify its energy sector, including investments in renewables and increased natural gas production. Regional tensions, including the Iran-Israel conflict, present ongoing risks to Saudi energy infrastructure, particularly in the Eastern Province, which hosts much of the country’s oil production. Any Iranian-backed attacks, such as those conducted by the Houthi rebels in Yemen, could disrupt Saudi oil production and exports, as seen in the 2019 drone attacks on Aramco facilities.

Overarching Challenges

The Russia-Ukraine War and the Iran-Israel conflict, while differing in nature and geographic context, both impact regional and global energy security. The Russia-Ukraine War has led to direct impacts on Europe’s energy infrastructure and supply, while the Iran-Israel conflict presents longer-term risks to the stability of global energy flows. These conflicts reveal contrasting mechanisms of disruption: the Russia-Ukraine War has accelerated the shift in energy dependencies and diversification efforts in Europe, while the Iran-Israel conflict threatens to undermine the security of key oil transit routes and perpetuate instability in the Middle East, a crucial region for oil trade globally.

The Russia-Ukraine War has led to immediate disruption of energy security, particularly in Europe. Since the war began in February 2022, Russian gas exports to Europe have been dramatically reduced due to sanctions, and Russia’s use of energy as a strategic tool has affected gas exports to Europe. The war has disrupted energy infrastructure in Europe, including pipelines and storage facilities, and significantly impacted Ukraine’s energy grid, leaving the country reliant on emergency imports from its European neighbors. The direct impact on gas flows, especially through pipelines such as Nord Stream, has forced European countries to rapidly diversify their energy sources and establish alternative supply routes.

Baltic countries and Poland have led efforts to diversify their energy sources, increasing imports of LNG from the U.S., Qatar, and other suppliers. Lithuania has effectively ended its reliance on Russian gas by developing a domestic LNG terminal, while Poland has ramped up LNG imports and expanded its capacity to receive energy from non-Russian sources. This shift in energy policy reflects the urgency brought about by the energy disruptions linked to the Russia-Ukraine War. The conflict has hastened Europe’s efforts to transition to renewable energy sources, including wind and solar, while at the same time pushing for closer integration of European energy markets to buffer against future disruptions. The war has made energy security a pressing issue in Europe, leading to both short-term solutions such as LNG imports and long-term strategies like expanding renewable energy infrastructure.

In contrast, the Iran-Israel conflict presents indirect risks to global energy security due to potential impacts on critical maritime routes. The conflict, characterized by proxy wars, nuclear tensions, and strategic rivalries, does not directly target energy infrastructure in the same way as the Russia-Ukraine War. However, it has the potential to escalate and disrupt vital maritime routes, particularly the Straits of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandab. The indirect impact of the conflict lies in its capacity to heighten tensions in the Middle East, a region critical to global energy markets, and to involve major oil producers like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Iran itself.

While the Iran-Israel conflict has not yet led to immediate global supply disruptions, it poses long-term risks by threatening the stability of key transit routes and oil production facilities. A potential escalation involving Israel and Iran could impact the flow of oil from the Arabian Gulf, affecting European energy supplies and leading to a spike in global oil prices. For major oil exporters like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, the conflict increases the risk of potential disruptions to their energy infrastructure, as evidenced by the 2019 drone strikes on Saudi Aramco facilities, carried out by Iranian-backed Houthi rebels.42 These indirect consequences of the Iran-Israel conflict, while less visible than the disruptions in Europe, could have profound long-term effects on global energy security, particularly if the conflict escalates into a broader regional war.

The response to the Russia-Ukraine War has involved rapid and visible shifts in energy dependencies and diversification efforts, while the Iran-Israel conflict has led to more gradual adjustments focused on securing key transit routes and finding alternative corridors. In Europe, the immediate need to replace Russian gas has resulted in concrete policy changes and infrastructure investments. European countries have moved quickly to build LNG terminals, increase imports from alternative suppliers, and invest in renewable energy sources. The EU has accelerated its Green Deal initiatives and REPowerEU plan, setting new targets for reducing fossil fuel dependency and increasing clean energy use in response to the war.

In contrast, the Iran-Israel conflict, while not prompting the same rapid diversification of energy sources, has led global actors to focus more on securing vital maritime routes and stabilizing the Middle East. The threat posed by Iran’s control over the Straits of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandab has pushed oil-importing countries to consider alternative shipping routes. The UAE’s investment in the Habshan-Fujairah pipeline and Saudi Arabia’s efforts to revitalize energy security through diversification and renewable energy are responses to the risks posed by the ongoing Iran-Israel conflict. These strategies reflect a longer-term approach to mitigating indirect threats to energy security, as opposed to the immediate and direct responses seen in Europe.

The future impact of the Russia-Ukraine War and the Iran-Israel conflict on energy security is likely to reshape global energy strategies. Europe’s continued shift away from Russian gas could lead to new supply challenges, higher energy costs, and a faster-than-expected push toward renewable energy technology. At the same time, the Iran-Israel conflict poses risks to key oil transit routes, and potential escalations could impact oil supply and cause price volatility. To mitigate these risks, countries must diversify their energy sources by investing in LNG terminals, expanding renewable energy infrastructure, and securing alternative supply routes. Facilitating the resilience of energy infrastructure, both against physical and cyber threats, will be crucial, especially for nations dependent on vulnerable supply chains.

International cooperation, such as Europe’s collective energy strategies and new alliances like the Abraham Accords, can promote regional stability and create shared energy resources. Additionally, accelerating investment in renewable energy will not only reduce dependency on volatile fossil fuel markets but also offer a sustainable, future-proof solution to energy insecurity driven by geopolitical conflicts. While Saudi Arabia has not yet become a member of the Abraham Accords, there are ongoing discussions and speculation regarding its potential inclusion.43 Any formal alignment with Israel through the Accords would be a substantial geopolitical shift, which would have far-reaching implications for regional energy security and stability. The economic and security ties between Israel and the Gulf states would likely be fortified by Saudi Arabia’s involvement, which could potentially generate new opportunities for energy cooperation, such as the security of oil transit routes or collaborative renewable energy projects. On the other hand, Europe’s increasing reliance on U.S. LNG as a substitute for Russian gas introduces both short-term and long-term challenges. In the immediate aftermath of the Russian supply interruption, U.S. LNG has facilitated the prevention of energy shortages in Europe. Nevertheless, Europe may be at risk of price volatility as a result of the fluctuating global LNG markets if it continues to rely on U.S. LNG. LNG prices are more sensitive to market fluctuations compared to pipeline gas, which is often governed by long-term contracts. LNG infrastructure necessitates substantial investment, including storage facilities and terminals.

Conclusion

The Russia-Ukraine War and the Iran-Israel conflict have highlighted vulnerabilities in global energy security, though their impacts differ in nature and scope. The Russia-Ukraine War has had direct impacts on the European energy supply, prompting a rapid shift away from Russian gas and oil while contributing to Europe’s increased focus on renewable energy. The importance of resilient energy infrastructure is evident in the progress made by Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia to reduce their dependence on Russian energy. While Ukraine’s energy system has sustained significant damage, its efforts to secure alternative imports highlight its capacity to adapt amid geopolitical disruptions. In contrast, the Iran-Israel conflict presents indirect risks to global energy security, especially regarding key oil transit routes. Although widespread supply disruptions have not yet been the result of the conflict, the potential for escalation continues to pose a significant threat to global energy markets. Regional actors, including the UAE and Saudi Arabia, are investing in renewable energy and diversification initiatives to strengthen their energy sectors. Geopolitical tensions in the region continue to create uncertainties for long-term energy security. Both conflicts underscore the importance of energy diversification, infrastructure resilience, and international cooperation. Investing in alternative supply routes and renewable energy sources can help mitigate long-term risks associated with geopolitical tensions, supporting nations in their efforts to enhance energy security. The intersection of energy security and geopolitics highlights the need for a sustainable model of energy cooperation capable of withstanding geopolitical disruptions.

References

[1] Winzer, Christian, “Conceptualizing Energy Security.” Electricity Policy Research Group, July 2011, https://api.repository.cam.ac.uk/server/api/core/bitstreams/0daf0f42-2d40-4102-8686-59e2fa2fb88d/content.

[2] Martínez-García, Miguel Á., Carmen Ramos-Carvajal, and Ángeles Cámara, “Consequences of the Energy Measures Derived From the War in Ukraine on the Level of Prices of EU Countries,” Resources Policy 86 (September 7, 2023): 104114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.104114.

[3] Janeliūnas, Tomas, “Energy Without Russia: The Case of Lithuania,” Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung – Politics for Europe, 2022, https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/budapest/20409.pdf.

[4] Pekic, Sanja, “Paldiski LNG Terminal in Estonia Step Closer to Completion.” Offshore Energy, March 30, 2022, https://www.offshore-energy.biz/paldiski-lng-terminal-in-estonia-step-closer-to-completion/.

[5] Ministry of Climate and Environment, “Poland Terminated the Gas Agreement on the Yamal Gas Pipeline – Ministry of Climate and Environment – Gov.pl Website,” May 27, 2022, https://www.gov.pl/web/climate/poland-terminated-the-gas-agreement-on-the-yamal-gas-pipeline.

[6] Europetrole, “ORLEN Increases LNG Import Capacity,” August 21, 2023, https://www.euro-petrole.com/orlen-increases-lng-import-capacity-n-i-25954.

[7] Stelzenmüller, Constanze, and Samantha Gross. “Europe’s Messy Russian Gas Divorce,” Brookings, June 18, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/europes-messy-russian-gas-divorce/.

[8] Snyder, John, “Without Russian Supply, Poland Looks to US LNG and Norwegian Gas,” Riviera, April 11, 2023, https://www.rivieramm.com/news-content-hub/news-content-hub/without-russian-supply-poland-looks-to-us-lng-and-norway-gas-75706.

[9] Yagova, Olga, “Saudi-Polish Deal Dents Russian Oil Dominance in Baltic,” Reuters, January 17, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/saudi-polish-deal-dents-russian-oil-dominance-baltic-2022-01-17/.

[10] Mackenzie, Lucia, and Gabriel Gavin, “Most of Europe Is Fine Without Russian Gas,” POLITICO, October 11, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/russian-gas-deal-europe-ukraine-pipeline-energy-market-lng/.

[11] Payne, Julia, “EU Energy Ministers Discuss Ukraine Energy Crisis, Russian LNG,” Reuters, October 15, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/eu-energy-ministers-discuss-ukraine-energy-crisis-russian-lng-2024-10-15/.

[12] Borrell, Josep, “Closing the Tap on Russian Gas Re-exports,” EEAS, June 26, 2024, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/closing-tap-russian-gas-re-exports_en.

[13] Corbeau, Anne-Sophie, and Tatiana Mitrova, “Russia’s Gas Export Strategy: Adapting to the New Reality,” Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University SIPA | CGEP, February 21, 2024, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/publications/russias-gas-export-strategy-adapting-to-the-new-reality/.

[14] Xu, Muyu, “Iran’s Expanding Oil Trade With Top Buyer China.” Reuters, November 23, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/irans-expanding-oil-trade-with-top-buyer-china-2023-11-10/.

[15] “Iran Adds 60mcm/D to Its Gas Production Capacity: NIGC Head,” Shana, May 9, 2024, https://en.shana.ir/news/641204/Iran-Adds-60mcmd-to-its-Gas-Production-Capacity-NIGC-Head.

[16] Bowden, Julian, “East Med Gaza Crisis Tightens Regional Gas Balances,” The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, November 2023, https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/East-Med-%E2%80%93-Gaza-crisis-tightens-regional-gas-balances.pdf.

[17] Bowden, Julian, and Elad Golan, “East Mediterranean Gas: A Triangle of Interdependencies,” The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, May 2024, https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Insight-151-East-Mediterranean-gas-%E2%80%93-a-triangle-of-interdependencies.pdf.

[18] “Jordan Seeks Renewal of Iraqi Oil Import Agreement,” Jordan Times, July 14, 2024, https://jordantimes.com/news/local/jordan-seeks-renewal-iraqi-oil-import-agreement.

[19] International Trade Administration | Trade.gov. “United Arab Emirates – Oil and Gas,” November 25, 2023, https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/united-arab-emirates-oil-and-gas.

[20] Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, “Saudi Arabia Facts and Figures,” 2024, https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/169.htm.

[21] “Export Volume of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) From Egypt 2011-2023,” Statista, August 1, 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1326874/export-volume-of-liquefied-natural-gas-from-egypt/.

[22] “Egypt Eyes Gas Production Increase,” CNBC Africa, Reuters, October 14, 2024, https://www.cnbcafrica.com/wire/651802/.

[23] Janeliūnas, “Energy Without Russia: The Case of Lithuania.”

[24] “KN Plans to Expand the Annual Regasification Capacity of Klaipėda’s LNG Terminal,” CEEnergy News, July 9, 2022, https://ceenergynews.com/lng/kn-plans-to-expand-the-annual-regasification-capacity-of-klaipedas-lng-terminal/.

[25] “Baltic Gas Market,” Skultelng, 2022. https://www.skultelng.lv/en/baltic_gas_market/#:~:text=In%C4%8Dukalns%20UGS%20of%202.3%20bcm,bcm%2C%20Estonia%20~0.6%20bcm.

[26] “REPowerEU: One Year Later_Latvia,” Energy.EC.Europa,EU 2024, https://energy.ec.europa.eu/document/download/4124469f-ff1a-4b8f-8813-44096d2fb8fc_en?filename=LV_REPowerEU.pdf.

[27] Ibid.

[28] IEA, “Executive Summary – Estonia 2023 – Analysis – IEA,” n.d. https://www.iea.org/reports/estonia-2023/executive-summary.

[29] Publications Office of the European Union, “Estonia and the European Green Deal : Climate and Energy Targets in Estonia.” Publications Office of the EU, 2022, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/654f85aa-db11-11ec-a95f-01aa75ed71a1/language-en#:~:text=To%20fight%20the%20climate%20crisis,%2C%20buildings%2C%20agriculture%20and%20waste.

[30] IEA, “Ukraine’s Energy System Under Attack – Ukraine’s Energy Security and the Coming Winter – Analysis – IEA,” 2024, https://www.iea.org/reports/ukraines-energy-security-and-the-coming-winter/ukraines-energy-system-under-attack.

[31] OHCHR, “Sept. 2024 – Attacks on Ukraine’s Electricity Infrastructure Threaten Key Aspects of Life as Winter Approaches | UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine,” September 19, 2024, https://ukraine.ohchr.org/en/Attacks-On-Ukraines-Electricity-Infrastructure.

[32] UNDP, “Uncovering the Reality of Ukraine’s Decimated Energy Infrastructure,” April 12, 2023, https://www.undp.org/eurasia/blog/uncovering-reality-ukraines-decimated-energy-infrastructure.

[33] Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure Israel, “Export,” 2024, https://www.energy-sea.gov.il/home/export/.

[34] Meredith, Sam, “Why Oil and Gas Markets Are Dreading the Risk of Supply Disruption in the Strait of Hormuz.” CNBC, October 8, 2024, https://www.cnbc.com/2024/10/08/strait-of-hormuz-what-supply-disruption-could-mean-for-oil-markets.html#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20oil%20flow%20in,of%20the%20global%20crude%20trade.

[35] “Updated Threats to Shipping in the Red Sea,” Skuld, May 16, 2024, https://www.skuld.com/topics/port/piracy/updated-threats-to-shipping-in-the-red-sea/.

[36] Kuoman, Andrea, “Red Sea on Edge: Houthi Attacks Disrupt Vital Shipping Routes,” Universidad De Navarra Global Affairs and Strategic Studies, February 16, 2024, https://www.unav.edu/web/global-affairs/red-sea-on-edge-houthi-attacks-disrupt-vital-shipping-routes.

[37] Wrobel, Sharon, “Israel Grants Initial Approval for Additional Gas Exports From Leviathan Reservoir,” Times of Israel, June 26, 2024, https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-grants-initial-approval-for-additional-gas-exports-from-leviathan-reservoir/.

[38] International Trade Administration | Trade.gov., “Energy Resource Guide – United Arab Emirates – Oil and Gas,” 2021, https://www.trade.gov/energy-resource-guide-united-arab-emirates-oil-and-gas.

[39] Hydrocarbons Technology, “Abu Dhabi Crude Oil (Habshan-Fujairah) Pipeline Project – Hydrocarbons Technology,” November 29, 2021, https://www.hydrocarbons-technology.com/projects/abu-dhabi-pipeline/.

[40] UAE, “UAE Energy Strategy 2050,” Official Portal of the UAE Government,” May 7, 2024, https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/strategies-plans-and-visions/environment-and-energy/uae-energy-strategy-2050.

[41] Pistilli, Melissa, “Top 10 Oil-producing Countries (Updated 2024),” Nasdaq, August 14, 2024, https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/top-10-oil-producing-countries-updated-2024.

[42] Associated Press, “Major Saudi Arabia Oil Facilities Hit by Houthi Drone Strikes.” The Guardian, September 14, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/14/major-saudi-arabia-oil-facilities-hit-by-drone-strikes.

[43] Walla, Katherine, “A Saudi-Israeli Deal Is Not Happening Just yet. But There Are Other Ways to Expand the Abraham Accords,” Atlantic Council, September 15, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/a-saudi-israeli-deal-is-not-happening-just-yet-but-there-are-other-ways-to-expand-the-abraham-accords/.