On 21 May 2023, Prime Minister (PM) Kyriakos Mitsotakis’s center-right New Democracy (ND) party won an unexpected 41% of the vote share, which was more than double that of its nearest contender, Alexis Tsipras’s left-wing Syriza party, which only received 20%. Since neither party passed the 50% threshold in the 300-seat parliament, elections went to a second round on 25 June. Mitsotakis entered the run-off in a more advantageous position due to the new electoral system that grants 20+ additional seats to the front-runner candidate, and with over 40% of the votes, he comfortably gained 158 seats in the parliament and the mandate to govern till 2027.[1] Only 53% of eligible voters turned out in the second round of the election, compared to 88% in neighboring Turkey, for instance.[2]

Mitsotakis’s popularity is due to the country’s economic progress, his ability to manage tensions with Turkey, and the promise of political stability.[3] This is evident in the support he receives from the European Union (EU) and the United States (US) despite the challenges facing the country. Greece’s ten-year bonds are on the brink of returning to investment grade and inflation is down to 3%.[4] Its debt-to-GDP ratio is still at an enormous 178%, but the country is firmly anchored on a recovery path even if it is expected to take decades.[5] Unlike what Tsipras had hoped for, issues such as the wiretapping scandal that involved the intelligence service (EYP) and even Mitsotakis’s family, the high unemployment rate, catastrophic train crash, and controversial mistreatment of immigrants did not suffice to swing votes in the opposition’s favor.

Greek voters usually lean toward the left in the political spectrum, but the ND has delivered its promises of growth, foreign investment, increases in pension payments, and salary raises, which ultimately attracted more voters.[6] Voters preferred the continuation of a strong, established government. In 2015, the Syriza government had a bitter controversy with the “Troika” of the European Commission (EC), European Central Bank (ECB), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) about the austerity package to rescue the Greek economy. The then PM Tsipras even passed a popular referendum against proposed fiscal measures, but then abruptly rejected the outcome and accepted the Troika’s conditions. He resigned after having lost the elections in 2019, giving up his seat to Mitsotakis.

Transcending this internal political rivalry, one key topic, if not the most important one in Greece, is its relations with Turkey. The year 2023 marks the centennial anniversary of the Republic of Turkey as well as the signing of the Lausanne Treaty with Greece in 1923. Moreover, coincidentally, Turkey’s presidential and general elections also took place in 2023, with the first round being held on 14 May and the run-off on 28 May. In the interim period between the two elections, Mitsotakis praised Turkey’s more prudent approach toward Greece after the earthquakes in February, but said that he was under “no illusions as to the possibility of changing long-term trends in foreign policy.”[7]

Meanwhile, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan made his first foreign visit, after securing a third term, to the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), the northeast portion of a de facto divided island recognized only by Turkey. During his visit, Erdoğan stressed that Turkey’s “road map is based on peace,” but sent a thinly veiled message to Athens that “things can be different if there would be those who try to prevent peace.”[8] Although the positive atmosphere with Greece seems to have opened a rare window of opportunity for Ankara to tackle more contentious issues, underlying geopolitical tensions persist and rhetoric can easily turn harsh as the recent statements of the respective leaders above demonstrate. This article unpacks the political dynamics in the lead up to the elections and offers insights into what to expect in the new equilibrium.

Greece’s economic woes

In the early 2010s, Greece suffered a sovereign debt crisis that left its mark on the country through poverty, social strife, and discontent with the political establishment. The outcome also had a crucial impact on the country’s foreign relations at a regional level. Greece lost almost a third of its GDP as unemployment reached 28% in 2014.[9] Problems had actually started to brew earlier than the much-blamed US subprime mortgage crisis of 2007, when Greece joined the Eurozone in 2004. Greece’s decision to seek entry to the European Monetary Union (EMU) and Eurozone, and its accession to the Union, were premature. The currency bloc’s “rules were not observed,”[10] and there should have been better monitoring, scrutiny, and discipline applied in the EMU’s accession criteria.

For Greece, the monetary efficiency gain from the adoption of the euro would be high if the magnitude of economic transactions between Greece and the EMU was high, and factors of production could move freely within the Eurozone. But the EU is not an optimum currency area because markets are not adequately integrated through flows of goods, capital, and labor. To produce a net gain on balance, monetary efficiency gains minus the economic stability loss that Greece would realize from joining the EMU should have been positive. The challenge was that Greece did not cross that minimum threshold of integration with other European economies that could produce sufficiently high gains on efficiency. Its inflation rate, unemployment rate, and fiscal policy differed vastly from the other members. The country has lower levels of physical capital per worker and less highly-skilled labor than its northern counterparts in the EU. In fact, according to former chief economist of the ECB, Otmar Issing, “Greece cheated to join [the Eurozone].”[11]

Having surrendered its ability to use monetary policy, Greece’s situation quickly became unsustainable due to heavy public borrowing and exorbitant expenditures in the early to mid 2000s, especially for the Olympic Games in 2004. After the onset of the global financial crisis in 2007, as borrowing costs rose and financing dried up, the Greek government was unable to service its mounting debt.[12] It had to endure a more costly slump for domestic prices and wages to adjust, due to a less-than-adequate level of integration with the Eurozone and lack of ability to stimulate output through monetary and fiscal policy. The “Troika” of the EC, ECB, and the IMF agreed to haircut some of Greece’s debt and restructure the rest through a bailout program between 2010-2018.

Greece suffered a crushing economic contraction with political repercussions, not only in the domestic sphere but also in the foreign policy arena. It successfully exited the last bailout program in 2018, with spending controls ending in 2022, although it still owed US$350 billion to the EU and IMF.[13] But the program anchored Greece firmly in the Western-led neoliberal institutionalist camp spearheaded by the IMF and ECB. Had the former PM Alexis Tsipras held onto his popular mandate after winning the snap elections in 2015 and renegotiated bailout terms with the “Troika”, it could have set in motion a more autonomous policy-making dynamic in Athens and served as a cushion against pressures from Berlin, Brussels, and Washington. By implication, its approach toward Turkey between 2016-2023 could have been set in more equitable terms on a bilateral level rather than be susceptible to conditions dictated by its creditors.

Greek foreign policy in the post-2019 era

Alexis Tsipras was a progressive figure outside of Greece’s traditional elites – the Mitsotakis, Papandreou, Venizelos, and Karamanlis families, who had dominated the political scene since the late nineteenth/early twentieth century. He was a grassroots leader who, together with then finance minister Yannis Varoufakis, tried to break Greece free from its subservient place in the center-periphery dichotomy with the West. When he failed in his attempt to build a welfare state and resigned from his position as PM in 2019, ND’s Kyriakos Mitsotakis formed a conservative government that, unlike Syriza, was much more aligned with the US and EU’s perception of the world.

A graduate of Stanford and Harvard Business School, Mitsotakis served as the CEO of the National Bank of Greece and was nominated as the “Global Leader of Tomorrow” by the World Economic Forum in 2003.[14] Like other political dynasties in Greece, he had strong bonds with the financial world in London and New York. His father Konstantinos Mitsotakis was the PM of Greece between 1990-1993, while his sister Dora Bakoyannis served as Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2006-2009. However, like his predecessor Tsipras, Mitsotakis had to confront chronic issues like corruption, deficiencies in public service, and the dire consequences of austerity measures on people.

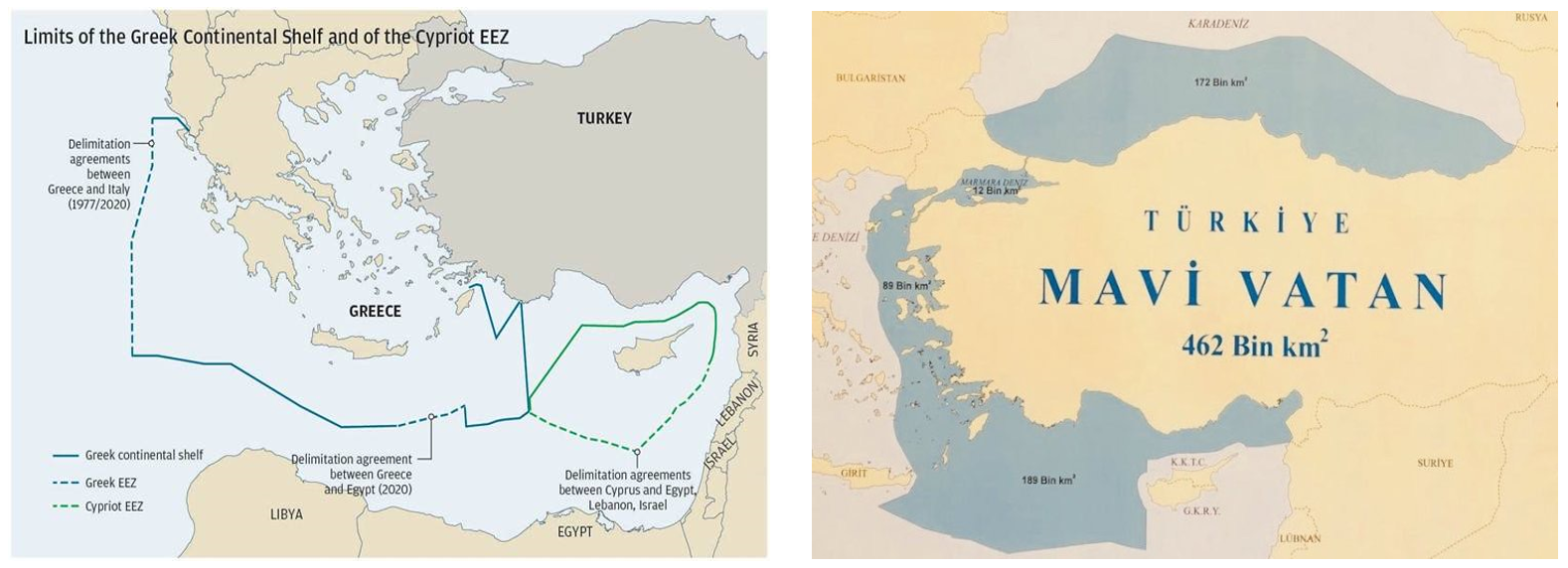

When Mitsotakis took the helm, Greece faced a resurgent Turkey that posed a more assertive, activist stance in the Aegean Sea and the Mediterranean via its “Blue Homeland” concept. Supported by President Erdoğan, progenitors of this concept advocated that Ankara should take rightful ownership of maritime zones in areas that clashed with Greece’s claims. They put forward a map (Figure 1 below) that showed the proposed boundaries of Turkey’s exclusive economic zones (EEZ) and refuted Greek claims to sovereignty on certain islands/rock formations in disputed areas, also known as “gray zones”.

After the failed coup attempt in Turkey (2016), several military officers with ties to FETÖ (Fethullah Gülen) sought refuge in Greece and allegedly provided classified information to the Greek authorities.[15] As Turkey-US relations deteriorated, quite naturally, the foreign policy contours of the Greek government also followed a hardline approach toward Ankara. Turkey’s political standoff with the West was a godsend for the hawks in Athens. In particular, Erdoğan’s impulsive rhetoric referencing the Greek islands, such as “we might suddenly come one night” (bir gece ansızın gelebiliriz),[16] provided Mitsotakis with a useful trump card, which he deviously leveraged in Washington and Brussels to his advantage. The combative atmosphere catapulted a series of reprisals that escalated tensions to the brink of war in 2020, when the two sides clashed over offshore energy rights in the Eastern Mediterranean. Greece subsequently opened its doors wide to increased US military presence and bases on its territories and inked massive arms procurement deals. Through Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreements (MCDA) with France and the US, it acquired commitment to “mutual defense assistance” from both countries, similar to the assurance under NATO Article 5.[17]

Figure 1. Greece’s Claims to Maritime Zones vs. Turkey’s Blue Homeland

Sources: SLPress (Kathimerini Atlas), http://bitly.ws/zGsK; Önce Vatan, http://bitly.ws/zGtn

As is often the case, “foreign policy presents itself as a glorious terrain for injecting hope to a demoralized population.”[18] Ironically, in the last election, like Turkish President Erdoğan, Mitsotakis prioritized the country’s security and asked his supporters for votes by referring to Turkey as “a case of stability”.[19] In his playbook, “the vote is a decision between security under the [ND’s] continued governance [versus] instability and adventurism under Tsipras and Syriza.”[20] The distinguishing factor between the electoral campaigns of Erdoğan and Mitsotakis is that Turkey always came under the spotlight in Greece whereas Turkey did not devote as much attention to matters pertaining to Greece. In a recent survey by Kadir Has University in Istanbul, the Turkish public ranked the possibility of a conflict between the two countries as 12th on the list of ‘most important international issues in the next 10 years’, way below the Syrian war, climate change, cyber security, and even China’s rise.[21] Conversely, from 2019 till present, almost no day has passed with Turkey not making headlines in the Greek media, illustrating that the threat perception toward Turkey is a great determinant of political psychology in Greece, so much so that the commentary in Greek media about Turkey’s new cabinet after the May 2023 elections received greater coverage than the internal political debates in Athens.[22]

Implications of the election outcome on Greek-Turkish relations

Greek-Turkish relations have entered a “live and let live” détente since the earthquakes struck southern Turkey in February 2023. After a series of reciprocal meetings between foreign ministers, Ankara decided to support Greece’s bid for non-permanent membership to the UN Security Council (UNSC) in 2025-2026, and Athens returned the favor by lending support to Turkey’s bid for presidency of the International Maritime Organization (IMO).[23] Both countries applied a moratorium on military exercises over the summer and expressed their interest in resuming talks on more sensitive issues.[24] On a global level, the balance of power is shifting from the Euro-Atlantic to Asia-Pacific, the world order is evolving into one of multipolarity, and the US influence over the region is declining.[25] In this context, Ankara prefers to keep Greece at arm’s length and focus on issues that require immediate attention like the war in Ukraine, reconciliation with Syria, and economic relations with the Gulf countries. Greece is also keen to keep channels of dialogue open to avoid putting at risk its delicate economic recovery program.

There are a dozen files on competing claims of sovereignty between the two neighbors over territorial rights, breadth of maritime zones, and air space, not to mention other topics of friction such as the Turkish-Muslim minority in Western Thrace and the Greek-Orthodox Patriarchate in Istanbul. Disputed geographic areas are a continuous source of contention. These issues date back to as early as the 1930s and there have been numerous rounds of negotiations in bilateral and multilateral settings without a positive outcome. The fact that there are conservative, hardline governments in both countries now makes a breakthrough even more unlikely. Relations will not fall back to the tense days of 2020 if cooler heads prevail,[26] but the current window of opportunity might not last very long.

This is because, apart from economic reasons, there is little political incentive for Greece to invest in durable, equitable, comprehensive solutions to sensitive issues through compromise with Turkey. The appointment of hard-liners such as Nikos Dendias to the Ministry of Defense and Giorgos Gerapetritis to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs after the cabinet reshuffle in Athens attest to the fact that Greece will continue its hawkish stance toward Turkey. The conversative government in Ankara is also disinterested in making politically controversial giveaways to Athens. The appointment of Hakan Fidan to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and İbrahim Kalın to the National Intelligence Agency (MİT) in Ankara signals a carrot-and-stick approach to regional issues but more importantly a continuation of Turkey’s quest for strategic autonomy in its national security and foreign policy.

Furthermore, the strategic culture in both countries is deeply nationalistic, antagonistic, and suspicious of the other. Relatively more conciliatory opposition parties in both countries are weak. Neither side can tolerate losses of sovereignty without a test of their power on the field. Their underlying interests will remain for the foreseeable future, with geopolitical issues outliving transitory periods of softening during economic downturns. Once the summer tourism season is over, the tendency to score points by demonstrating an act of resolve on either side might come back.

Where Turkey is concerned, all Greek political parties are united around the government’s position no matter what their differences are otherwise. Still, the Greek government is likely waiting at least until the complete delivery of the F-16 Block 70 upgrades, plus potentially F-35s from the US, and Rafales from France, before it considers making a move to advance its interests in the Aegean Sea or the Mediterranean. That will take until 2028 at the earliest, a time by which today’s positive atmosphere may no longer endure. As regards Cyprus, which is “the biggest thorn in Greek-Turkish relations,”[27] the election of hawkish candidate Nikos Christodoulides as president of the Greek-governed republic in the south implies that there is no solution perspective for a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation anymore. The situation is likely to make the two-state status quo on the island a permanent feature.

This is a space that should be watched very closely as it carries the risk of putting NATO’s southern flank in jeopardy and destabilizing the region further. Erdoğan is expected to continue the warm dialogue with Greece and refrain from inflammatory rhetoric or flexing of military muscles for a year or two, lest the country dives into an even deeper economic crisis. As is the case in Greece, Turkish opposition parties stand close to Erdoğan’s policy toward Athens although they propose more caution and more constructive dialogue than military activism as the preferred policy option. Still, it is highly likely that in the event of a hot incident, Erdoğan’s response will find support from political parties across the political spectrum. This is due as much to the rise of nationalism as to disenchantment with the West and perception of the EU/US policies toward Turkey as unfair. To maintain its edge, Turkey will develop its indigenous armament programs – which include the TAI Kaan fighter jet and Baykar Kızılelma unmanned combat aerial vehicle, as well as long-range missiles like Roketsan Tayfun – while integrating more closely with North Cyprus.

On a positive note, what is more achievable on a bilateral level is cooperation in areas of common interest such as trade and tourism, particularly maritime shipment, air transport, and railroads. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) publishes its Liner Shipping Connectivity Index based on the criteria of container capacity, number of vessels, and number of shipping companies.[28] Accordingly, Turkey and Greece are interdependent in maritime commerce, more so than, for instance, Turkey and Israel, even though their positions on geopolitical matters fundamentally differ. Climate action, renewable energy, illegal immigration, and academic exchanges are other important areas of converging interests that both sides could focus on.[29] The best approach at this point is to put discussion of more contentious issues on hold until both sides are more confident, more flexible, and more accommodating of each other.

Conclusion

On the centennial anniversary of the Lausanne Treaty of 1923, Greece and Turkey held decisive elections that set the contours of their domestic political spheres and foreign policy trajectory for the next 4-5 years. Unless early elections are called in either country, the conservative governments in both Ankara and Athens – which spent considerable political capital to advance their interests to the detriment of the other – are here to stay. “Disaster diplomacy” in the aftermath of the devastating earthquakes in Turkey and the tragic train crash in Greece created a conducive atmosphere and opened a window of opportunity for dialogue. But this situation is unlikely to last for very long due to inherently opposing geopolitical interests and strategic cultures between the two sides. Greece is unable to chart an autonomous policy of genuine rapprochement with Turkey due to its close economic, defense, and security ties with the West, while Turkey is unwilling to dedicate time and attention to browbeating with Greece and re-asserting its positions due to the high economic costs and more pressing priorities. Nationalism is a major factor now in both countries, which makes it unrealistic to expect any meaningful change in underlying interests or compromise on contentious issues in the Aegean and the Mediterranean. Focusing on developing bilateral trade ties and cultural diplomacy is probably the best legacy that both countries can hand down to future generations.

References

[1] “ND Wins Landslide Election Victory for Second 4-Year Term, EKathimerini.com, June 25, 2023, http://bitly.ws/JKEN.

[2] Elena Becatoros and Derek Gatopoulos, “Greece’s Conservative New Democracy Party Wins Landslide Election Victory for Second 4-Year Term,” ABC News, June 25, 2023, http://bitly.ws/JKFr.

[3] “The Guardian View on the Greek Election: The New Hegemony,” The Guardian, May 22, 2023, http://bitly.ws/JKGn.

[4] “Why Greece Is One Step Away from an Investment-Grade Rating,” Goldman Sachs, May 19, 2023, http://bitly.ws/JKGY.

[5] “Greece National Government Debt, 1999–2023,” CEIC Data, http://bitly.ws/JKI9.

[6] Soli Özel and Dimitrios Triantaphyllou, “Elections in Turkey and Greece: Strengthening or Straining Relations?” Webinar Discussion, Columbia Global Centers, Istanbul, Turkey, June 15, 2023.

[7] Vassilis Nedos, “Mitsotakis: No Illusions about Turkey” EKathimerini.com, June 13, 2023, http://bitly.ws/JKJP.

[8] “Recognition of Turkish Cyprus Only Way for Negotiations: Erdoğan,” Hürriyet Daily News, June 12, 2023, http://bitly.ws/JKKx.

[9] “Greece Jobless Rate Hits New Record of 28%,” BBC News, February 13, 2014, http://bitly.ws/JKLp.

[10] Christian Wienberg, “Greece ‘Cheated’ to Join Euro, Former ECB Economist Issing Says,” Bloomberg, May 27, 2011, http://bitly.ws/JKLF.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “1974-2018: Greece’s Debt Crisis,” Council on Foreign Relations, http://bitly.ws/JKMC.

[13] “Greece: Economic Indicators, Historic Data & Forecasts” CEIC Data, http://bitly.ws/JKNj.

[14] Delphi Economic Forum, “Kyriakos Mitsotakis,” http://bitly.ws/JM4k.

[15] Taşkin Su, “Devletin Gizli Cihazı Yunanistan’ın Elinde,” Sözcü, September 10, 2021, http://bitly.ws/JWnr.

[16] “Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan: Bir Gece Ansızın Gelebiliriz,” Habertürk TV [Video], September 6, 2022 http://bitly.ws/JWpu.

[17] “France and Greece Hedge Their Bets with a New Defence Pact,” The Economist, October 2, 2021, http://bitly.ws/JWra; U.S. Department of State, “Agreement Between the United States of America and Greece: Amending Agreement of July 8, 1990, as Extended,” October 5, 2019, http://bitly.ws/JWro.

[18] Vassilis Paipais, “‘Greek’ Expectations: Broaching the Case for a European Exclusive Economic Zone,” London School of Economics and Political Science, March 14, 2013, http://bitly.ws/JM56.

[19] Yorgo Kırbaki, “Türkiye’yi Örnek Gösterdi, Oy İstedi,” Hürriyet, June 7, 2023, http://bitly.ws/JM5w.

[20] Akis Georgakellos and Mylonas Harris, “An Election Won’t End Greece’s Troubles,” Foreign Policy, May 19, 2023, http://bitly.ws/JM5M.

[21] Mustafa Aydın, Türk Dış Politikası Kamuoyu Algıları Araştırması – 2022, Quantitative Research Report (Istanbul: Kadir Has University-Global Academy-Akademetre, 2022), http://bitly.ws/JM63.

[22] “Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan’ın Sözleri Yunanistan’da Birinci Manşet: Türk Liderin Yeni Şahinleri,” Hürriyet, June 7, 2023, http://bitly.ws/JM7I.

[23] Yorgo Kırbaki, “Ankara ile Atina Hattında İlk Mutabakat,” Hürriyet, March 22, 2023, http://bitly.ws/JM8c.

[24] Vassilis Nedos, “Sense of Calm Prevails in the Aegean,” EKathimerini.com, March 22, 2023, http://bitly.ws/JP5G.

[25] Hasan Ünal, “Ege Sorunları ve Kıbrıs Meselesine Yeni Bakışlar” Kıbrıs Raporu, June 18, 2023), http://bitly.ws/JM8S.

[26] Özel and Triantaphyllou, “Elections in Turkey and Greece: Strengthening or Straining Relations?”

[27] Ibid.

[28] UNCTAD STAT, “Maritime Transport,” http://bitly.ws/JM9w.

[29] Özel and Triantaphyllou, “Elections in Turkey and Greece: Strengthening or Straining Relations?”