Global energy dynamics are undergoing a transformative shift, driven by the need to reduce carbon emissions and transition toward sustainable energy sources. Green hydrogen, produced through electrolysis powered by renewable energy, is emerging as a pivotal solution in the global decarbonization effort. As an energy carrier, it holds the potential to decouple economic growth from fossil fuel dependency, offering a pathway toward achieving carbon neutrality while ensuring energy security.

The European Union (EU) has positioned green hydrogen at the core of its energy transition strategy, particularly in its REPowerEU plan, which aims to phase out dependency on Russian fossil fuels. The EU has set ambitious targets, including achieving climate neutrality by 2050 and securing 10 million tons of green hydrogen production domestically while importing an additional 10 million tons by 2030.1 In this context, North Africa emerges as a strategic partner due to its vast renewable energy potential, particularly in solar and wind power. With abundant solar radiation, North Africa presents a prime location for large-scale green hydrogen production. Countries such as Algeria, Morocco, Egypt, and Tunisia have been identified as key players in this sector, given their ability to harness cost-effective renewable energy and their geographical proximity to European energy markets. By leveraging existing and repurposed natural gas infrastructure, North Africa could become a major supplier of green hydrogen to Europe, strengthening bilateral energy partnerships while enhancing regional economic development.

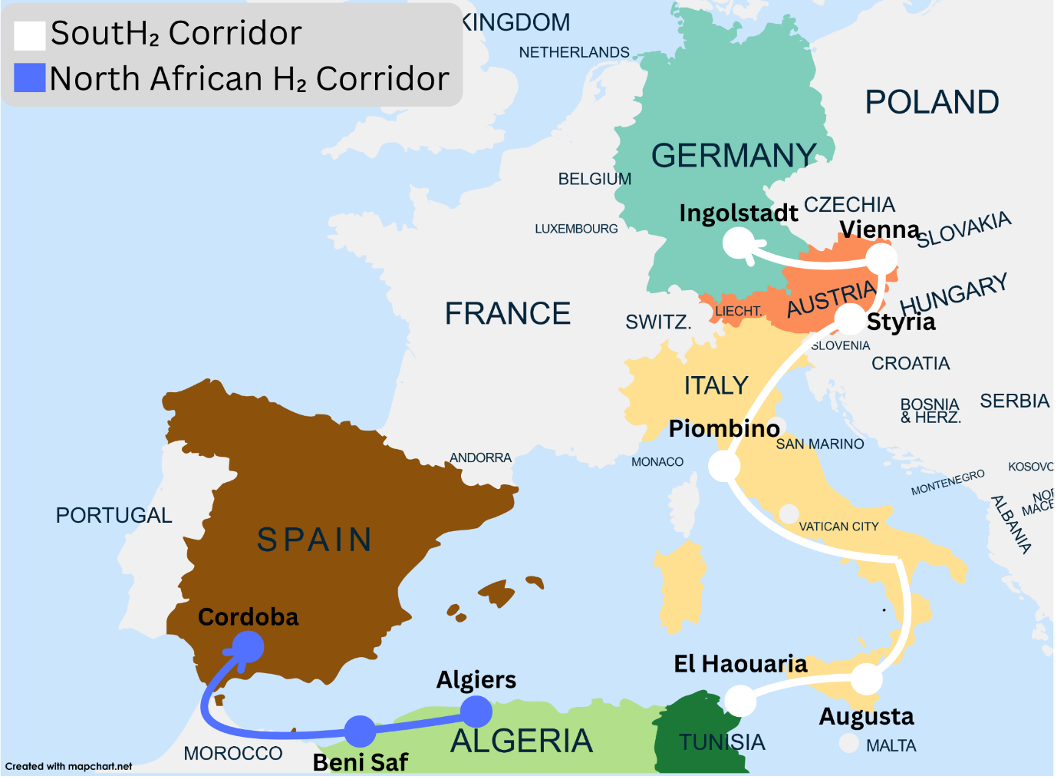

Green hydrogen corridors refer to cross-border energy networks that facilitate the production, transportation, and distribution of hydrogen between regions. These corridors are essential in linking North Africa’s hydrogen production capacity with Southern Europe’s industrial demand, utilizing existing gas pipelines and new infrastructure where necessary. One of the most ambitious projects in this domain is the Southern Hydrogen Corridor (SoutH2 Corridor), a 3,300-4,000 km hydrogen pipeline system connecting North Africa with Italy, Austria, and Germany.2 The economic and strategic benefits of these corridors extend beyond energy trade. They play a crucial role in enhancing European energy security, reducing reliance on volatile fossil fuel markets, and promoting regional economic integration between North Africa and Europe.3 By encouraging investment in hydrogen production and transportation, these corridors also contribute to job creation, technology transfer, and long-term economic diversification in North African nations. Furthermore, green hydrogen corridors support the EU’s Hydrogen Strategy, which emphasizes interconnectivity and sectoral integration for achieving large-scale decarbonization.4

This paper aims to analyze the strategic development of green hydrogen corridors between North Africa and Southern Europe, focusing on their role in the global energy transition. It will examine North Africa’s green hydrogen production potential by evaluating the renewable energy capacity, infrastructure, and investment landscape. Southern Europe’s role as a consumer and transit region will be assessed through industrial demand, existing pipeline infrastructure, and market readiness. Opportunities for economic cooperation and energy security are identified in mutual benefits and policy frameworks supporting hydrogen trade, while challenges in infrastructure, geopolitics, and environmental sustainability through financial constraints and potential geopolitical risks in energy cooperation.

The development of green hydrogen corridors between North Africa and Southern Europe is not merely an economic endeavor but a strategic necessity for achieving global climate goals. This initiative aligns with international commitments such as the Paris Agreement and the EU Green Deal, underscoring the importance of regional cooperation in the energy transition. By exploring the technological, economic, and political dimensions of hydrogen trade between North Africa and Europe, this paper will contribute to the broader discourse on sustainable energy infrastructure and cross-regional cooperation. Green hydrogen corridors represent a blueprint for promoting energy independence, accelerating decarbonization, and strengthening Euro-African energy relations in the decades to come.

Figure 1: Map of Proposed Green Hydrogen Corridors

Source: Authors’ creation using Canva & mapchart.net

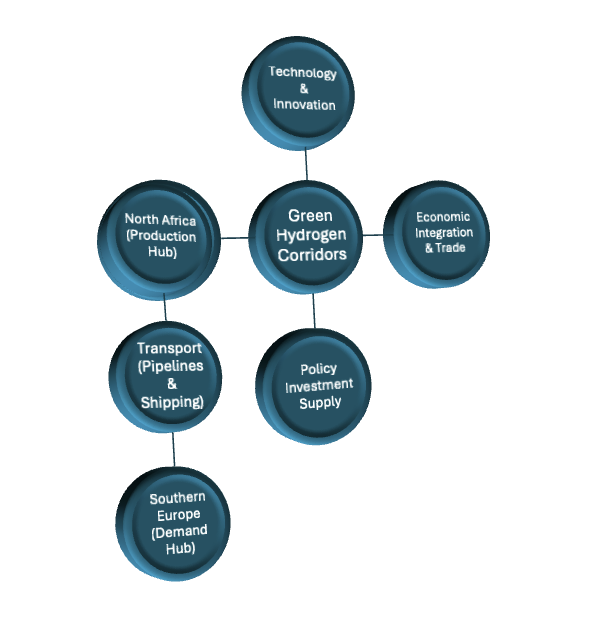

Green Hydrogen Corridors

Green hydrogen is rapidly emerging as a cornerstone in the global energy transition. Produced by splitting water through electrolysis powered entirely by renewable energy sources such as solar and wind, green hydrogen offers a virtually carbon‐free fuel alternative for decarbonizing sectors where electrification is challenging.5 As the world seeks sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels, establishing dedicated infrastructure to produce, store, and transport green hydrogen is vital. One of the most promising strategies is the creation of green hydrogen corridors that link regions with abundant renewable energy resources to those with strong demand and established infrastructure.

Amid ongoing discussions about hydrogen’s role in the energy transition, there is growing consensus that our focus must shift from merely “green hydrogen” to a broader concept of “clean hydrogen.” As Professor Phil Hart observes, by specifying “clean,” the production framework can be widened to include non-electrolyzing methods, thereby expanding the technological pathways beyond conventional electrolysis.6 This nuanced approach not only opens the door to more diverse and potentially cost‐effective production techniques but also aligns with emerging trends in energy storage, such as advanced battery systems for hourly to 12‑hour storage needs, and the promising applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning for optimizing grid performance. Together, these innovations are pivotal for developing a hydrogen economy that is both environmentally and economically robust, paving the way toward the 2050 net-zero ambitions.7

At the same time, the economic challenges linked to green hydrogen remain a subject of active debate. Alyssa Norris highlights that e-fuel skeptics argue the high cost of green hydrogen renders e-fuels prohibitively expensive, suggesting that these fuels may not achieve economic viability for decades compared to other sustainable fuel options.8 Despite this, Frank Wouters emphasizes green hydrogen’s unique capacity to connect regions where it can be produced at low cost with areas that face high energy demand, underscoring its potential as a critical link in diversified energy trade.9 This vision is further supported by calls for enhanced policy and financial support, aimed at bridging the cost gap and building the requisite infrastructure. Such collaborative efforts are essential to ensure that hydrogen not only contributes to decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors but also strengthens energy security while promoting economic growth across regions.10

Green hydrogen distinguishes itself from other forms of hydrogen production by its use of renewable energy sources for electrolysis. Unlike gray hydrogen, which is produced from natural gas without carbon capture, and blue hydrogen, which adds carbon capture to natural gas reforming, the green variant leaves no carbon footprint during production.11 Its significance lies in its ability to provide a versatile, clean energy carrier that can be used in industries such as steel production, heavy transport, and even power storage. With increasing global investments in renewable energy and growing commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, green hydrogen is increasingly seen as the “missing link” in achieving climate targets such as those outlined in the Paris Agreement.12 Moreover, the concept of hydrogen valleys, local ecosystems that integrate the production and consumption of hydrogen, is evolving into larger, interconnected networks. These networks, or corridors, link clusters of hydrogen valleys across regions.13 By connecting North Africa’s production capabilities with Southern Europe’s demand centers and transit networks, green hydrogen corridors offer a strategic solution to challenges related to energy security, economic diversification, and cross-border trade.

North Africa is uniquely positioned to become a major green hydrogen production hub. The region has renewable energy potential in solar irradiation and strong wind currents. Countries such as Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt have already demonstrated significant capacity for renewable energy generation with projects like the Noor Ouarzazate solar complex and wind projects along coastal areas.14 These natural advantages translate into one of the lowest production costs for green hydrogen globally, making North Africa a lucrative location for large-scale hydrogen production. The geographic proximity of North Africa to Europe is another crucial factor. The relatively short distance reduces transport costs and enhances the feasibility of cross-border energy trade. North African nations can leverage existing gas pipelines, many of which are now being repurposed to transport hydrogen, to connect with Southern Europe. Recent projects and memoranda of understanding (MoUs) highlight growing interest and commitment; for instance, several landmark deals have been signed to develop gigawatt (GW) scale hydrogen plants in Mauritania and Tunisia, underscoring the region’s readiness to lead in green hydrogen production.15 Furthermore, North Africa’s vast available land and low water costs (albeit with necessary considerations regarding water scarcity) provide additional competitive advantages. Innovative solutions such as seawater desalination or wastewater recycling are being explored to ensure sustainable water management in the electrolysis process.16 In transitioning from fossil fuel exports to renewable hydrogen, North African countries not only align with global climate goals but also secure long-term economic growth and energy resilience.

Southern Europe, with its established energy infrastructure and growing renewable energy demand, plays a crucial role as both a consumer and transit hub for green hydrogen. EU policies such as the REPowerEU initiative and the European Hydrogen Strategy set ambitious targets for renewable energy adoption and decarbonization.17 Southern European countries, Italy, Spain, and Portugal in particular, are strategically positioned to act as gateways for green hydrogen imports. Their ports, existing gas pipeline networks, and hydrogen storage facilities are already being adapted to accommodate the new energy carrier.18 Southern Europe’s industrial base and dense urban centers create a steady and growing demand for clean energy. With a commitment to reducing dependence on fossil fuels and increasing energy independence, Southern Europe is ready to integrate imported green hydrogen into its energy mix. This integration supports not only power generation but also industrial processes and transportation networks, helping to decarbonize sectors that have been traditionally difficult to electrify.19 The region’s energy policies and infrastructure investments are designed to harmonize with EU climate targets. Initiatives such as the European Hydrogen Backbone (EHB) aim to establish a pan-European network of pipelines that connect hydrogen production sites with demand centers.20 As part of this effort, Southern Europe’s role extends beyond mere consumption; it becomes an active hub that facilitates hydrogen trade and distribution throughout the continent. The development of hydrogen corridors in Southern Europe is therefore not only a regional priority but also a critical component of the broader European energy security and decarbonization strategy.

The establishment of green hydrogen corridors between North Africa and Southern Europe offers several opportunities for collaboration that extend well beyond the energy sector. At its core, this cross-border initiative embodies economic integration by engaging stronger trade and investment ties between the two regions. Creating a dedicated infrastructure network for hydrogen trade is essential for both regions to benefit from enhanced energy security, enabling further diversification of energy sources and reducing dependency on fossil fuel markets.

Economic collaboration is further enriched by the development of joint projects and public-private partnerships. For instance, multinational energy companies and local governments can collaborate to finance, construct, and operate large-scale electrolysis plants, hydrogen storage facilities, and repurposed pipeline networks. The strategic use of existing infrastructure reduces capital expenditure and accelerates project timelines.21 In addition, the corridors can serve as catalysts for innovation, spurring the development of new technologies in electrolysis, hydrogen storage, and transportation. Moreover, these corridors can help bridge technological and expertise gaps between regions. Southern Europe’s advanced research institutions and renewable energy companies can share knowledge and technology with North African producers, promoting a mutual learning environment.22 This collaboration not only improves efficiency and reduces costs but also creates opportunities for workforce development and capacity building in both regions.

Green hydrogen corridors also have a significant decarbonization impact. By replacing fossil fuels in heavy industry, transport, and power generation, hydrogen can play a transformative role in reducing carbon emissions. As both regions commit to ambitious climate targets, the corridors become an integral part of their collective strategy to meet EU climate objectives and global sustainability goals.23 The integrated approach, from production in sun-drenched North Africa to consumption in industrial Southern Europe, ensures that the benefits of decarbonization are distributed across multiple sectors and economies.

Figure 2: Key Factors in Green Hydrogen Corridors

Source: Authors’ creation using Microsoft SmartArt

One of the foremost concerns is the need for substantial investment in infrastructure. Upgrading and repurposing existing gas pipelines, constructing new hydrogen storage facilities, and ensuring efficient distribution networks require significant capital outlays.24 While repurposing existing assets can help mitigate costs, substantial gaps remain in the logistics chain that must be addressed through coordinated investment and policy support. Geopolitical and regulatory challenges also pose potential obstacles. The corridor spans multiple countries, each with its own political dynamics and regulatory frameworks. Harmonizing policies, safety standards, and environmental regulations across borders is critical to ensuring the operation of the hydrogen corridors. Moreover, political instability or changes in government policy in any part of North Africa or Southern Europe could delay or disrupt the development process.

Environmental concerns must also be carefully managed. Hydrogen production through electrolysis is water-intensive, a challenge that needs to be addressed in arid regions of North Africa. Sustainable water management strategies, including the use of desalinated seawater or recycled wastewater, are essential to minimize environmental impacts.25 Furthermore, while green hydrogen itself is environmentally benign, the full life-cycle assessment of its production, storage, and transportation must be evaluated to ensure that the overall benefits outweigh the associated environmental costs.

Although the European market is increasingly committed to renewable energy, the cost-competitiveness of green hydrogen compared to gray or blue hydrogen remains a subject of debate. The economics of scale, technological advancements, and supportive policy frameworks will be crucial to bridging this cost gap. Without targeted subsidies, tax incentives, or carbon pricing mechanisms, green hydrogen may struggle to achieve widespread adoption in the near future.26

The developments in this region have broader implications that resonate with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and the global energy landscape. The GCC, particularly the UAE, is increasingly involved in facilitating cross-border hydrogen projects and technology transfers. The UAE’s strategic role, through investments and partnerships with European and North African stakeholders, demonstrates its growing ambition to be a global leader in the green hydrogen economy.27 The initiatives pursued along the North Africa-Southern Europe axis provide valuable lessons for other regions seeking to harness the potential of green hydrogen. They illustrate how regional cooperation, supported by infrastructure and aligned policy frameworks, can create a competitive edge in the global energy market. Furthermore, by setting an example of successful cross-border integration, these corridors pave the way for similar projects that could link emerging hydrogen markets in Asia, the Americas, or other parts of Africa with regions that have strong demand for renewable energy.

International partnerships are expanding beyond the bilateral framework. Strategic alliances involving the UAE, Italy, and Albania are also shaping the future of cross-border renewable energy cooperation in the Mediterranean.28 These partnerships extend the green hydrogen initiatives to include broader renewable energy projects, such as GW-scale solar and wind installations combined with advanced storage solutions and are designed to create integrated energy networks that facilitate economic growth and energy security across continents.

North Africa’s Potential as a Green Hydrogen Hub

North Africa’s solar irradiation and favorable wind conditions have made it an attractive candidate for large‐scale renewable energy generation. In Tunisia, despite renewables currently comprising only about 3% of the electricity mix, there is a burgeoning recognition of the opportunity to leverage green hydrogen to decarbonize heavy industries, sectors that account for nearly 30% of the nation’s energy consumption.29 Local initiatives, supported by international bodies such as UNIDO, are actively working to build technical and institutional capacity. These efforts aim to train technicians and align education with the demands of the emerging green hydrogen value chain, thereby ensuring that the benefits of this energy transition extend to workforce development and local economic diversification.

One particularly illustrative development is Tunisia’s increasing involvement in landmark projects. A recent MoU between Tunisia’s Ministry of Industry, Mines and Energy with major international energy firms, among them French developer HDF Energy30 and the joint venture TE H2 (a collaboration between TotalEnergies and EREN Groupe) with Austrian partner VERBUND, signals the start of a large-scale green hydrogen project known as “H2 Notos.”31 In its initial phase, this project is slated to produce approximately 200,000 tons of green hydrogen per year using electrolysers powered by onshore wind and solar installations, with desalinated seawater, addressing the water-intensive nature of electrolysis.32 Plans are already underway to scale production up to one million tons annually, positioning Tunisia as a key exporter via the evolving SoutH2 Corridor, a dedicated pipeline infrastructure intended to transport hydrogen to major European demand centers, including Italy, Austria, and Germany. These initiatives are part of Tunisia’s broader ambition to produce around 8.3 million tons of green hydrogen and its derivatives by 2050, with a substantial portion marked for export and a projected total investment of nearly €120 billion.33

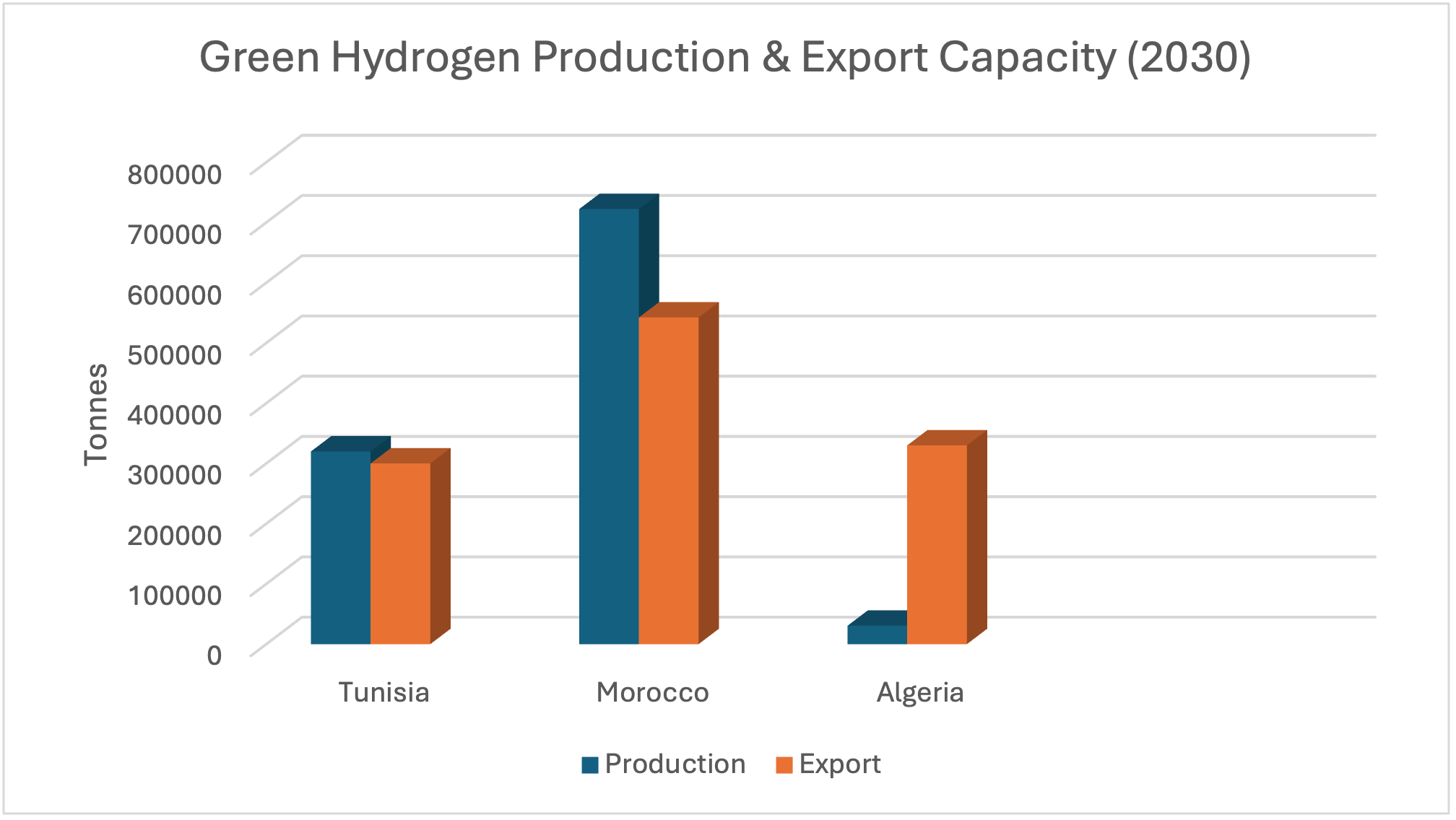

North Africa has the potential to become a major green hydrogen hub due to its abundant solar and wind resources, making hydrogen production cost-effective and scalable. The region boasts some of the highest solar radiation levels globally, particularly in Morocco, Algeria, and Egypt, where large-scale solar projects are already in place. For instance, Morocco’s Noor-Ouarzazate solar complex covers 3,000 hectares and produces 500 megawatts of energy daily, supporting the country’s green hydrogen ambitions.34 Additionally, Algeria possesses the largest wind energy potential in Africa, estimated at 7,700 GW if fully developed.35 These renewable resources, coupled with vast land availability and relatively low labor costs, position North Africa as a competitive hydrogen producer. Geographically, North Africa’s proximity to Europe is a key advantage. With the EU aiming to import 10 million tons of green hydrogen annually by 2030, North Africa’s export capacity could fulfill up to 40% of this demand if infrastructure and production goals are met.36 However, current projections suggest a gap between anticipated supply and the region’s actual production capabilities by 2030.

Mauritania has positioned itself at the forefront of North Africa’s hydrogen expansion. German project developer Conjuncta and the Mauritanian government signed a $34 billion agreement to develop a 10GW green hydrogen facility, one of the largest in Africa.37 This project, if completed on schedule, could provide a significant portion of North Africa’s hydrogen exports. Dubai-based AMEA Power has committed to building 1GW of green hydrogen capacity across Angola, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Mauritania.38 These projects, once operational, are expected to generate a total of 15GW of renewable electricity for green hydrogen production, further strengthening the continent’s role in the global hydrogen economy.39 Morocco has been particularly proactive in developing its green hydrogen strategy. The country signed an MoU with the EU to establish a Green Partnership and has targeted a 52% share of renewables in its energy mix by 2030.40

Government support is crucial in transforming North Africa into a green hydrogen hub. Countries in the region have introduced national hydrogen strategies aimed at attracting foreign investment and securing partnerships with Europe. Despite their commitments, Algeria anticipates producing only 30,700 tons of green hydrogen by 2030, and Tunisia expects to produce 300,000 tons, both of which fall significantly short of the EU’s projected demand.41 The 3,500-4,000 km hydrogen pipeline will connect Algeria and Tunisia to Italy, Austria, and Germany.42 When fully operational, it could supply over 4 million tons of hydrogen annually to Europe, equivalent to 40% of the EU’s 10-million-tonne hydrogen import target.43

Figure 3: Green Hydrogen Production and Export Projections in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia by 2030

Source: Authors’ creation using Microsoft SmartArt and adopting data from Climate Home News & Atalyar

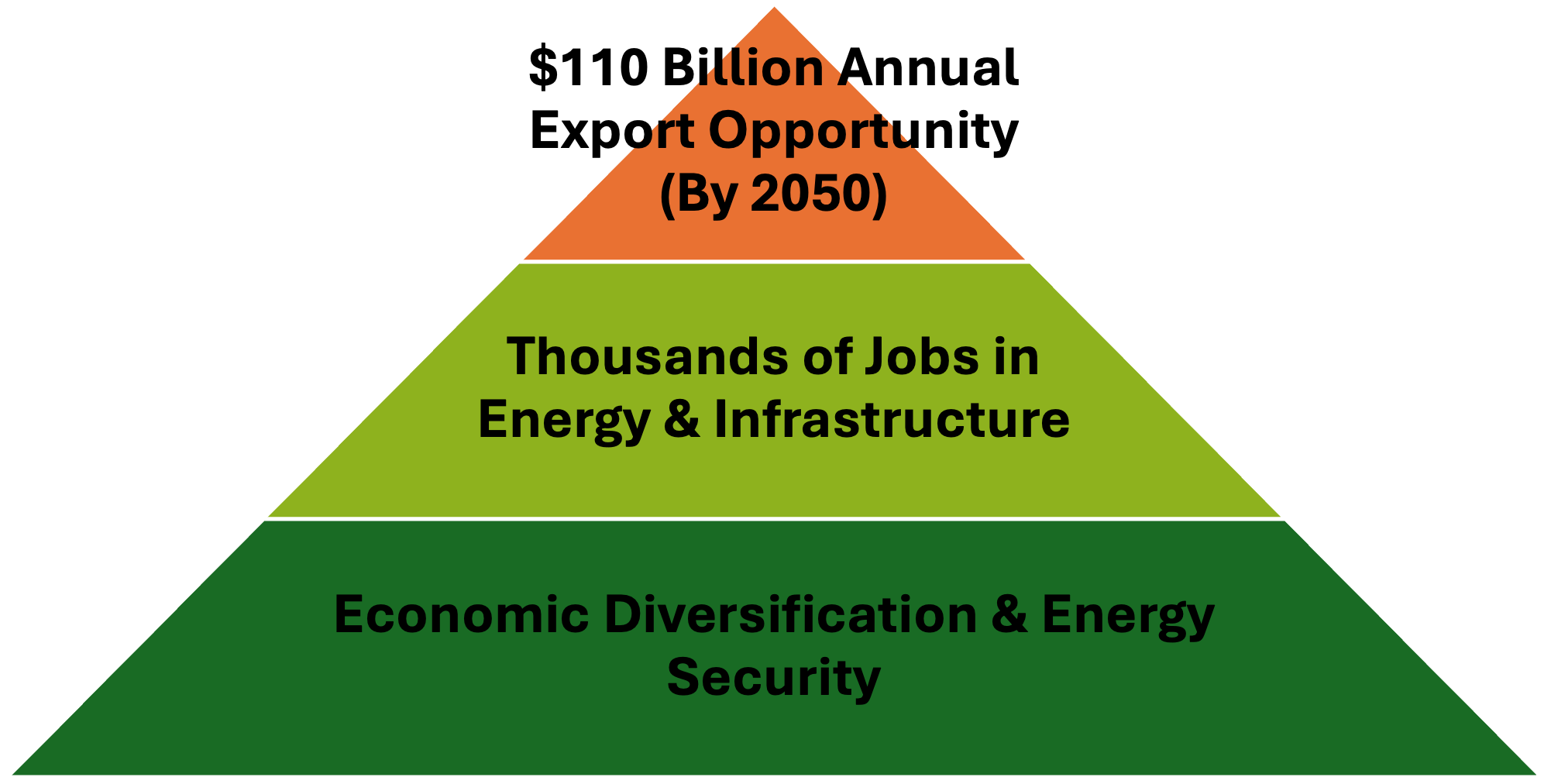

Green hydrogen production could provide a $110 billion annual export opportunity for North Africa by 2050, making it a key driver of economic diversification.44 The industry is expected to create thousands of jobs, particularly in renewable energy sectors, infrastructure development, and research. Many North African economies rely heavily on natural gas and crude oil exports, making them vulnerable to market fluctuations. Green hydrogen provides an alternative revenue stream, reducing dependence on fossil fuel markets and increasing energy trade stability. Green hydrogen development can enhance North Africa’s domestic energy security by increasing renewable energy penetration and reducing reliance on imported natural gas for power generation.

Figure 4: Green Hydrogen Economic Opportunities in North Africa

Source: Authors’ creation using Microsoft SmartArt

North Africa faces several hurdles in becoming a leading green hydrogen exporter. Hydrogen production via electrolysis is water-intensive, posing challenges in water-scarce regions like Algeria, Tunisia, and Egypt. Sustainable water management solutions, such as desalination and wastewater reuse, will be essential to mitigating these concerns. The hydrogen industry in Africa is still in its infancy, with less than 1% of global hydrogen production in 2023 classified as green.45 North Africa requires billions in infrastructure investment, particularly in electrolysis facilities, storage, and transport networks. The SoutH2 Corridor pipeline is expected to repurpose 65% of existing gas infrastructure, reducing costs but still requiring significant upgrades and regulatory approvals.46 Political instability and inconsistent regulatory frameworks in North Africa create uncertainties for investors. EU hydrogen demand credibility remains uncertain, with some analysts questioning the feasibility of the 2030 hydrogen import targets. Delayed projects are a common trend: A study tracking 200 global hydrogen projects found that only 7% were completed on schedule, highlighting execution risks.47

Despite these challenges, North Africa remains one of the most cost-competitive green hydrogen production regions globally. By 2035, Africa could supply 25 million tons of green hydrogen to global markets, meeting 15% of the EU’s projected gas replacement needs.48 North Africa’s green hydrogen production potential aligns with Southern Europe’s infrastructure and demand, creating a mutually beneficial energy corridor. North Africa’s experience in scaling green hydrogen could serve as a blueprint for other developing regions, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. If infrastructure, policy frameworks, and investment incentives align, North Africa can solidify its role as a global leader in green hydrogen production, supplying European markets while driving economic growth and sustainability in the region.

Southern Europe as a Gateway and Key Consumer of Green Hydrogen

Southern Europe has the potential to play a pivotal role in the emerging green hydrogen market as a transition hub between North Africa and the rest of Europe. Positioned as the first entry point for hydrogen imports, the region serves as both a gateway and a primary consumer, facilitating the transit of hydrogen to Central and Northern Europe. Its strategic location, coupled with pre-existing infrastructure development, makes Southern Europe an essential component of the EU’s decarbonization strategy and energy transition goals.

The geographical proximity to North Africa provides a natural advantage for hydrogen imports. The region is emerging as an energy transit hub, with Spain, Italy, and Portugal leading efforts to develop hydrogen infrastructure that can accommodate imports from North Africa. The Mediterranean Hydrogen Corridor and the SouthH₂ Corridor facilitate cross-border hydrogen trade aimed at establishing direct pipeline connections.49 The Southern Hydrogen Corridor, which recently gained momentum with a Joint Declaration of Intent signed in Rome, underscores the growing collaboration between Germany, Algeria, Italy, Austria, and Tunisia. This corridor aims to transport up to 163 terawatt hours of green hydrogen annually to Europe, with the infrastructure relying on repurposed natural gas pipelines.50

In playing a pivotal role in the green hydrogen economy, Southern Europe acts as both an entry point and a distribution hub for hydrogen imports from North Africa. Given that North Africa possesses some of the highest solar and wind energy potential, the ability to harness these resources for green hydrogen production and efficiently transport them to Europe is of strategic importance. Moreover, Southern Europe functions as an energy transit hub, ensuring that green hydrogen reaches Central and Northern Europe through integrated infrastructure networks. With the EU aiming to import 10 million tons of renewable hydrogen by 2030 under the REPowerEU plan, Southern Europe is set to play a crucial role in achieving this target.51 The EHB envisions significant pipeline expansions in the region, further reinforcing its position as a key transit zone. In addition to its role as a transit hub, Southern Europe is also a major consumer of green hydrogen due to its increasing demand for renewable energy. Countries in the region are accelerating their decarbonization efforts, investing over €5 billion collectively in hydrogen infrastructure and subsidies to reduce dependency on fossil fuels.52

One of the most ambitious projects in the region is the EHB, which aims to integrate Southern Europe into a vast hydrogen pipeline network linking North Africa with the rest of Europe. The H2Med project, announced in late 2022, is a key initiative that will connect Portugal, Spain, and France and is expected to extend the capacity of green hydrogen annually by 2030.53 Spain recently contributed to green hydrogen development, with multiple hydrogen corridors, port terminals, and blending projects under development. The Spanish government has allocated €1.55 billion under its Recovery Transformation and Resilience Plan to support the hydrogen sector, targeting the installation of 11GW of electrolysers by 2030.54 Italy has also made strategic investments, particularly in pipeline expansion and hydrogen storage. Furthermore, Italy has allocated €3.64 billion for hydrogen infrastructure development.55 The country’s Mediterranean connectivity, particularly with North Africa, strengthens its role as a crucial transit state. Portugal’s hydrogen strategy is centered around the Sines Green Hydrogen Valley, a 630-megawatt green hydrogen plant that aims to produce 62,000 tons of green hydrogen annually.56 With the lowest levelized cost of hydrogen in Europe, Portugal has a competitive advantage in green hydrogen production and export. Additionally, Southern Europe is investing heavily in hydrogen storage and distribution systems to improve its capability to manage large-scale hydrogen imports.

The EU has laid out a comprehensive hydrogen strategy, with Southern Europe playing a key role in its implementation. The EU Hydrogen Strategy highlights the need for robust import infrastructure, and Southern European nations are responding with ambitious national hydrogen roadmaps. The REPowerEU Initiative has significantly accelerated green hydrogen investments, particularly in hydrogen corridors linking North Africa and Europe. Under this initiative, Southern European countries are receiving substantial EU funding to develop hydrogen pipelines and ports. Portugal’s roadmap focuses on achieving 5.5 GW of electrolysers by 2030.57 The rise of green hydrogen suggests significant economic opportunities for Southern Europe. According to IRENA, job creation is expected to surge, with green hydrogen projected to generate up to 3.8 million jobs by 2030 and 6.5 million by 2050.58 The Southern European region as a strategic point can re-export green hydrogen to other EU markets.

Despite its advantages, several challenges remain. North Africa’s political instability affects the reliability of hydrogen imports. Algeria’s reluctance to rapidly transition to hydrogen and ongoing political tensions between Morocco and Algeria pose risks to energy security. Southern Europe’s energy security is tied to cross-border collaborations with North African nations. These partnerships are essential for ensuring stable hydrogen production, transport, and trade. Spain and Morocco have signed agreements to develop joint hydrogen projects, leveraging Morocco’s abundant solar and wind resources.59 Italy’s Mattei Plan seeks to strengthen the country as the Mediterranean’s primary hydrogen transit country.60 Furthermore, this cooperation has strengthened ties with Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya.61

Southern Europe is emerging as a global export gateway for green hydrogen, particularly with projects like H2Med and the EHB. The region’s infrastructure and policy framework provide it with a competitive edge in the international green hydrogen market. Moreover, Southern Europe’s experience can serve as a blueprint for other regions looking to develop hydrogen corridors and integrate renewable energy into their economies. The EU-GCC cooperation on green transition, which aligns Southern Europe with Gulf nations, highlights the global importance of hydrogen trade networks. Southern Europe’s geographical advantage, infrastructure investments, and policy framework position it as a crucial player in the green hydrogen economy. Despite challenges such as high infrastructure costs and geopolitical instability, the region’s strategic partnerships, economic potential, and regulatory support make it a potential bridge between North Africa’s production capacity and Europe’s green energy demand.

Conclusion

The establishment of green hydrogen corridors between North Africa and Southern Europe represents a critical step toward a decarbonized energy future. By leveraging North Africa’s renewable energy resources and Southern Europe’s advanced infrastructure and industrial demand, these corridors offer a viable pathway for achieving energy security, economic integration, and significant emissions reductions. However, realizing this vision requires a concerted effort from international stakeholders to address the financial, technical, and geopolitical challenges that could impede hydrogen trade.

To accelerate the development of these corridors, a set of strategic actions is recommended. First, North African and European policymakers must enhance regulatory harmonization to create a stable investment environment. Standardizing hydrogen certification, trade policies, and infrastructure regulations across both regions will facilitate cross-border cooperation and attract private sector investment. Additionally, financial incentives such as targeted subsidies and public-private partnerships should be expanded to reduce the cost gap between green hydrogen and conventional energy sources. Investment in infrastructure must be prioritized to ensure the viability of hydrogen transportation networks. While repurposing existing natural gas pipelines is a cost-effective strategy, new investments in dedicated hydrogen infrastructure, including electrolysis facilities, storage hubs, and port terminals, will be necessary to support long-term demand. The EU’s Hydrogen Strategy and the EHB must align with North African development plans to ensure an integrated and efficient supply chain.

Environmental sustainability considerations must also guide the development of green hydrogen corridors. Since electrolysis requires significant water resources, North African countries should invest in sustainable water management solutions such as desalination and wastewater recycling to mitigate the impact on local communities. Research and innovation in electrolysis efficiency, hydrogen storage, and transport technologies should be supported to enhance the sector’s environmental footprint and economic feasibility. Crucially, regional cooperation must extend beyond energy trade to encompass technology transfer, workforce development, and capacity building. Southern Europe’s expertise in renewable energy deployment and North Africa’s emerging green hydrogen industry can create a mutually beneficial exchange of skills and knowledge. Educational programs, technical training initiatives, and joint research projects should be encouraged to develop a skilled workforce capable of sustaining a hydrogen economy in both regions.

The long-term success of green hydrogen corridors will depend on geopolitical stability and strategic diplomacy. Strengthening Euro-African energy partnerships through multilateral agreements will ensure reliability and resilience in hydrogen trade. Given the growing global competition for clean energy leadership, Europe and North Africa can cooperate by promoting trust, transparency, and sustained cooperation. Green hydrogen corridors between North Africa and Southern Europe are more than an energy infrastructure project; they are a blueprint for regional energy independence, economic growth, and climate resilience. If the necessary policies, investments, and partnerships are implemented, these corridors can become a global model for clean energy cooperation, contributing to the broader goals of the Paris Agreement, the European Green Deal, and the worldwide transition toward a low-carbon future.

Endnotes

[1] “EHB Publishes Five Potential Hydrogen Supply Corridors to Meet Europe’s Accelerated 2030 Hydrogen Goals,” European Hydrogen Backbone, 2025, https://ehb.eu/newsitem/ehb-publishes-five-potential-hydrogen-supply-corridors-to-meet-europe-s-accelerated-2030-hydrogen-goals.

[2] “SoutH2 – the Initiative,” SoutH2, 2025, https://www.south2corridor.net/south2.

[3] Sergio Matalucci, “The Hydrogen Stream: Algeria, EU Nations Plan Southern Hydrogen Corridor,” PV Magazine International, January 21, 2025. https://www.pv-magazine.com/2025/01/21/the-hydrogen-stream-five-countries-sign-deal-for-4000-km-h2-corridor-from-northern-african-to-europe/.

[4] Roberto Cardinale, “From Natural Gas to Green Hydrogen: Developing and Repurposing Transnational Energy Infrastructure Connecting North Africa to Europe.” Energy Policy 181 (October 2023): 113623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113623.

[5] Enagás, “Hydrogen Valleys: A Local Vision for a Global Impact,” Good New Energy, May 5, 2022. https://goodnewenergy.enagas.es/en/innovative/hydrogen-valleys-a-local-vision-for-global-impact/.

[6] GtMedia, Masdar, and Abu Dhabi Department of Energy, The Future of Energy 2025, World Future Energy Summit, 71. https://edition.pagesuite.com/html5/reader/production/default.aspx?pubname=The%20Future%20Of%20Energy&pubid=1593ad04-93cd-4424-9f0d-e3652fe39a90.

[7] Ibid.

[8] GtMedia, Masdar, and Abu Dhabi Department of Energy, The Future of Energy 2025, 75.

[9] GtMedia, Masdar, and Abu Dhabi Department of Energy, The Future of Energy 2025, 77.

[10] GtMedia, Masdar, and Abu Dhabi Department of Energy, The Future of Energy 2025, 71.

[11] United Arab Emirates Ministry of Energy & Infrastructure, “National Hydrogen Strategy United Arab Emirates,” 2023, https://u.ae/-/media/Documents-2nd-half-2023/UAE-National-Hydrogen-Strategy-2023.pdf.

[12] European Clean Hydrogen Alliance, “Learnbook on Hydrogen Supply Corridors,” 2023, https://www.entsog.eu/sites/default/files/2023-04/web_entsog_230311_CHA_Learnbook_230418.pdf.

[13] Enagás, “Hydrogen Valleys: A Local Vision for a Global Impact.”

[14] N.J. Ayuk, “The Promise and Challenges of Green Hydrogen in North Africa,” Press Release, January 22, 2025, https://www.zawya.com/en/press-release/africa-press-releases/the-promise-and-challenges-of-green-hydrogen-in-north-africa-by-nj-ayuk-pesqeuvy.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Faïg Abbasov, Europe-Asia Green Corridors: Case for Morocco as a green shipping H2 hub, Transport & Environment, 2024, https://www.transportenvironment.org/uploads/files/Europe-Asia-Green-Corridors-Case-for-Morocco-as-a-shipping-green-H2-hub_TE-Imal.pdf.

[17] Enagás, “What Are the Future European Hydrogen Corridors?,” Good New Energy, August 22, 2022. https://goodnewenergy.enagas.es/en/innovative/what-are-the-future-european-hydrogen-corridors/.

[18] European Clean Hydrogen Alliance, “Learnbook on Hydrogen Supply Corridors.”

[19] Angeliki Menegaki, “Chapter 1 – an Editorial and an Introduction to the Economics of the Energy-growth Nexus: Current Challenges for Applied and Theoretical Research,” A Guide to Econometrics Methods for the Energy-Growth Nexus, 2021, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128190395000161.

[20] Enagás, “Future European Hydrogen Corridors.”

[21] Daniel Onyango, “African and European Countries Reaffirm Support for New Green Hydrogen Pipeline Project,” Pipeline Technology Journal, January 23, 2025. https://www.pipeline-journal.net/news/african-and-european-countries-reaffirm-support-new-green-hydrogen-pipeline-project.

[22] Ayuk, “Green Hydrogen in North Africa.”

[23] European Commission, “Key Cross-Border Infrastructure Projects,” November 19, 2021, https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/infrastructure/projects-common-interest-and-projects-mutual-interest/key-cross-border-infrastructure-projects_en.

[24] Ayuk, “Green Hydrogen in North Africa.”

[25] Abbasov, Europe-Asia Green Corridors: Case for Morocco as a green shipping H2 hub.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Maddalena Procopio and Corrado Čok, “Beyond Competition: How Europe Can Harness the UAE’s Energy Ambitions in Africa,” ECFR, June 20, 2024, https://ecfr.eu/publication/beyond-competition-how-europe-can-harness-the-uaes-energy-ambitions-in-africa/.

[28] “UAE, Italy, Albania Sign Tripartite Strategic Partnership Framework for Cross-border Green Energy Cooperation,” Emirates News Agency-WAM. January 15, 2025. https://www.wam.ae/article/bhpaq1w-uae-italy-albania-sign-tripartite-strategic.

[29] “Tunisia,” United Nations Industrial Development Organization, Global programme for Hydrogen in Industry, 2025, https://hydrogen.unido.org/tunisia.

[30] “France’s HDF Energy Plans a Large Green Hydrogen Project in Tunisia,” Enerdata, August 8, 2024, https://www.enerdata.net/publications/daily-energy-news/frances-hdf-energy-plans-large-green-hydrogen-project-tunisia.html.

[31] “Green Hydrogen: TE H2 Partners with VERBUND on a Large Project in Tunisia,” TotalEnergies, May 28, 2024. https://totalenergies.com/news/press-releases/green-hydrogen-te-h2-partners-verbund-large-project-tunisia.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Enerdata, “Large Green Hydrogen Project in Tunisia.”

[34] Rabah Arezki, “North Africa’s Hydrogen Mirage,” IMF, September 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2023/09/north-africa-hydrogen-mirage-rabah-arezki.

[35] Daniel Helmeci, “Realizing North Africa’s Green Hydrogen Potential,” Atlantic Council. February 2, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/energysource/realizing-north-africas-green-hydrogen-potential/.

[36] Sacha Shaw, “EU Backs North Africa Hydrogen Pipeline, but Is It a Green Dream?” Climate Home News, January 31, 2025. https://www.climatechangenews.com/2025/01/31/eu-backs-north-africa-hydrogen-pipeline-but-is-it-a-green-dream/.

[37] Arezki, “North Africa’s Hydrogen Mirage.”

[38] Procopio and Čok, “How Europe Can Harness the UAE’s Energy Ambitions in Africa.”

[39] Ibid.

[40] Helmeci, “Realizing North Africa’s Green Hydrogen Potential.”

[41] Shaw, “EU Backs North Africa Hydrogen Pipeline, but Is It a Green Dream?”

[42] SoutH2 Corridor. 2025. “SoutH2 Corridor – Our Connection for a Clean Future.” January 30, 2025. https://www.south2corridor.net/.

[43] Shaw, “EU Backs North Africa Hydrogen Pipeline, but Is It a Green Dream?”

[44] Liesel Venter, “Green Fuel to Catalyze Region’s Project Demand.” Breakbulk, November 22, 2023, https://breakbulk.com/articles/north-africas-hydrogen-pathway-potential.

[45] Carina Radford and Alex Field, “Green Hydrogen in Africa: A Continent of Possibilities?” White & Case LLP International Law Firm, Global Law Practice, December 19, 2023, https://www.whitecase.com/insight-our-thinking/africa-focus-winter-2023-green-hydrogen.

[46] SoutH2 Corridor, “SoutH2 Corridor – Our Connection for a Clean Future.”

[47] Shaw, “EU Backs North Africa Hydrogen Pipeline, but Is It a Green Dream?”

[48] Richard Willis, “New Study Confirms €1 Trillion Africa’s Extraordinary Green Hydrogen Potential,” European Investment Bank, December 21, 2022, https://www.eib.org/en/press/all/2022-574-new-study-confirms-eur-1-trillion-africa-s-extraordinary-green-hydrogen-potential.

[49] “Southern Hydrogen Corridor Gains Momentum with Joint Declaration Signed in Rome,” Hydrogen Europe, January 23, 2025, https://hydrogeneurope.eu/southern-hydrogen-corridor-gains-momentum-with-joint-declaration-signed-in-rome/.

[50] Matthew Goosen, “Algeria, Global Partners Formalize SoutH2 Green Hydrogen Pipeline Project,” Energy Capital & Power, January 27, 2025, https://energycapitalpower.com/algeria-global-partners-formalize-south2-green-hydrogen-pipeline-project/#:~:text=The%20project%20will%20repurpose%20natural,green%20hydrogen%20demand%20by%202040.

[51] Nora Aboushady and Alexia Faus Onbargi, “Green Hydrogen Partnerships Between the EU and the Southern Mediterranean: Challenges and Opportunities for Coherent and Just Energy Transitions,” IEMed, 2023, https://www.iemed.org/publication/green-hydrogen-partnerships/.

[52] IRENA, “Green Hydrogen Workshop Summary Report 2025,” World Future Energy Summit, January 15, 2025, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2025/Summary%20Report%20IRENA%20Green%20Hydrogen%20Workshop.pdf.

[53] Aboushady and Onbargi, “Green Hydrogen Partnerships Between the EU and the Southern Mediterranean.”

[54] “Webinar: Southern Europe H2 Potential | Connecting Green Hydrogen Europe 2025,” CHE, 2024, https://www.connectinghydrogeneurope.com/webinar-southern-europe-h2-potential.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Leigh Collins, “Portugal More Than Doubles Its Green Hydrogen Production Target for 2030,” Hydrogen Insight, July 3, 2023. https://www.hydrogeninsight.com/production/portugal-more-than-doubles-its-green-hydrogen-production-target-for-2030/2-1-1479355.

[58] IRENA, “Green Hydrogen Workshop Summary Report.”

[59] Adil Faouzi, “Morocco’s Potential as Europe’s Hydrogen Supplier Faces Challenges.” Morocco World News, February 20, 2024, https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2024/02/22983/moroccos-potential-as-europes-hydrogen-supplier-faces-challenges/.

[60] Emanuele Bompan, “Piano Mattei: The Three-card Trick at the Expense of Climate, Africa and Italy,” Renewable Matter, August 1, 2024. https://www.renewablematter.eu/en/piano-mattei-the-three-card-trick-at-the-expense-of-climate-africa-and-italy.

[61] Karim Mezran, “The Mattei Plan Is an Opportunity for North Africa,” Atlantic Council, July 29, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/mattei-plan-north-africa-italy/.