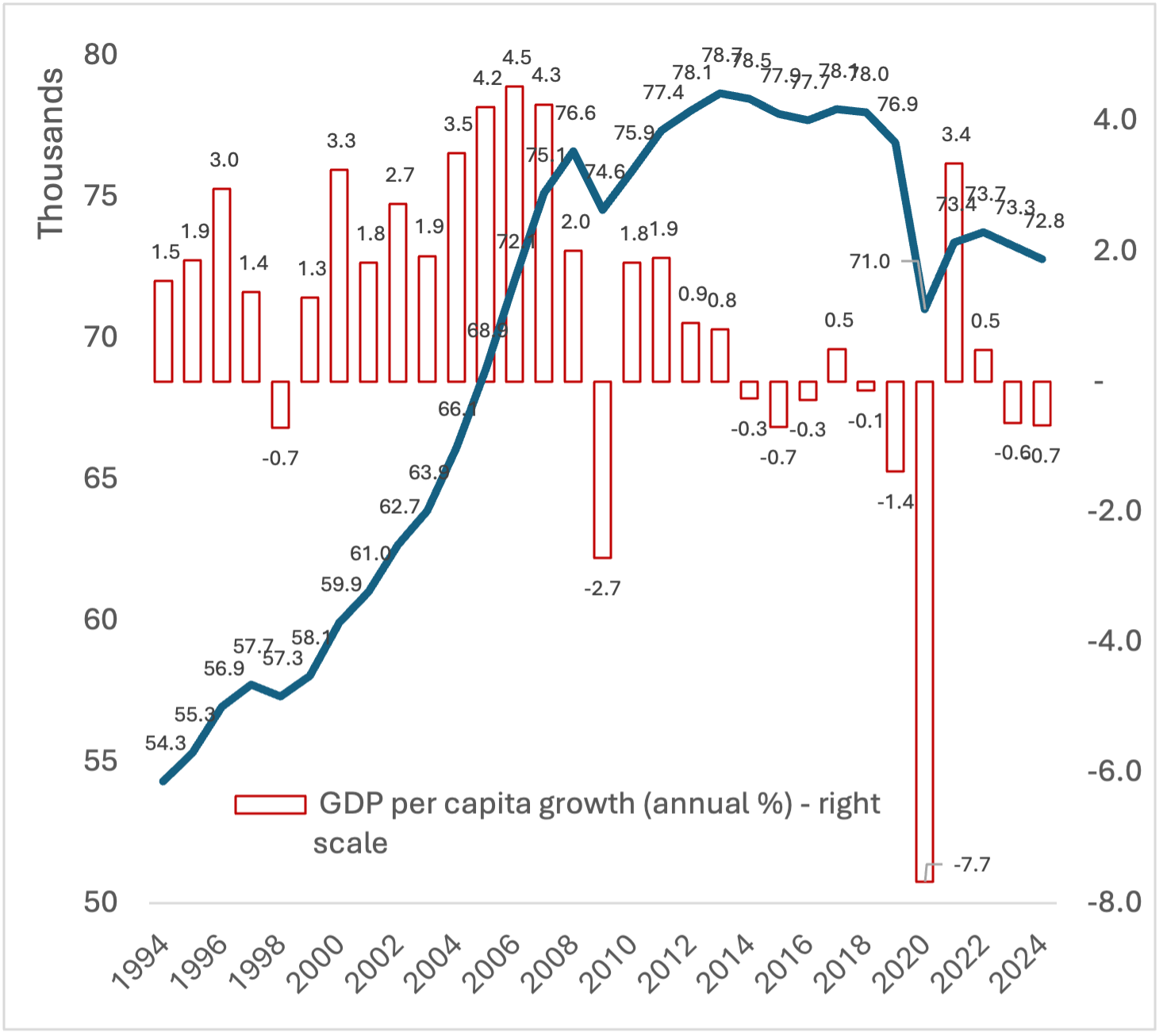

South Africa’s Vulindlela Phase 2 was recently launched on the back of moderately successful reforms under a Phase 1 program. Phase 2 goals are more ambitious, targeting an explicit improvement in GDP growth by 2030. A review of South Africa’s national economic programs suggests that its growth targets and list of reforms should be viewed with circumspection. Since the end of apartheid, South Africa has pursued five national programs. All fell short of their growth and reform targets. Given the deterioration in the enabling environment for national programs, the prospect of Vulindlela Phase 2 meeting its targets is limited. Since the most recent national growth program, launched in 2012, GDP per capita in real terms has regressed. This has coincided with declining bureaucratic effectiveness and a rising level of conflict between political and bureaucratic actors at various levels of executive government. For a country in the upper-middle-income bracket, this is disappointing as it is likely to be yet another missed opportunity to reach high-income status in the foreseeable future.

A mostly failed history of economic growth programs

South Africa’s post-apartheid national growth and development initiatives are a tale of half- to fully incomplete programs that, while initially having benefited from South Africa’s reintegration into the global economy, have increasingly had a negligible impact on economic growth.

The Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP), launched in 1994, was an ambitious initiative to rebalance the South African economy after decades of apartheid and centuries of colonial rule. The targets were ultimately not met across most benchmarks set. Implementation proved more complex than envisioned by policymakers, and the targets were too high.[1] South Africa’s devolved system of government, inability to manage private sector delivery partners and financial constraints are some of the many issues highlighted for the failure.

The RDP was followed by the Growth, Employment, and Redistribution (GEAR) program in 1996. GEAR combined approaches aligned with the market-oriented Washington Consensus policies of the 1980s and 1990s with concessions to organized labor that made labor markets more inflexible.[2] While South Africa applied a big bang approach to implementing these policies by lowering tariff barriers within a matter of years and implementing fiscal reforms, including making the central bank independent with a mandate to target inflation, the rigidities in the labor market meant that any structural changes to the economy GEAR unleashed as it reoriented itself toward an export orientation bumped into labor market rigidities that discouraged labor-absorbing economic activity. As a result, unemployment rose to over 27% by 2002 from 19% in 1996.

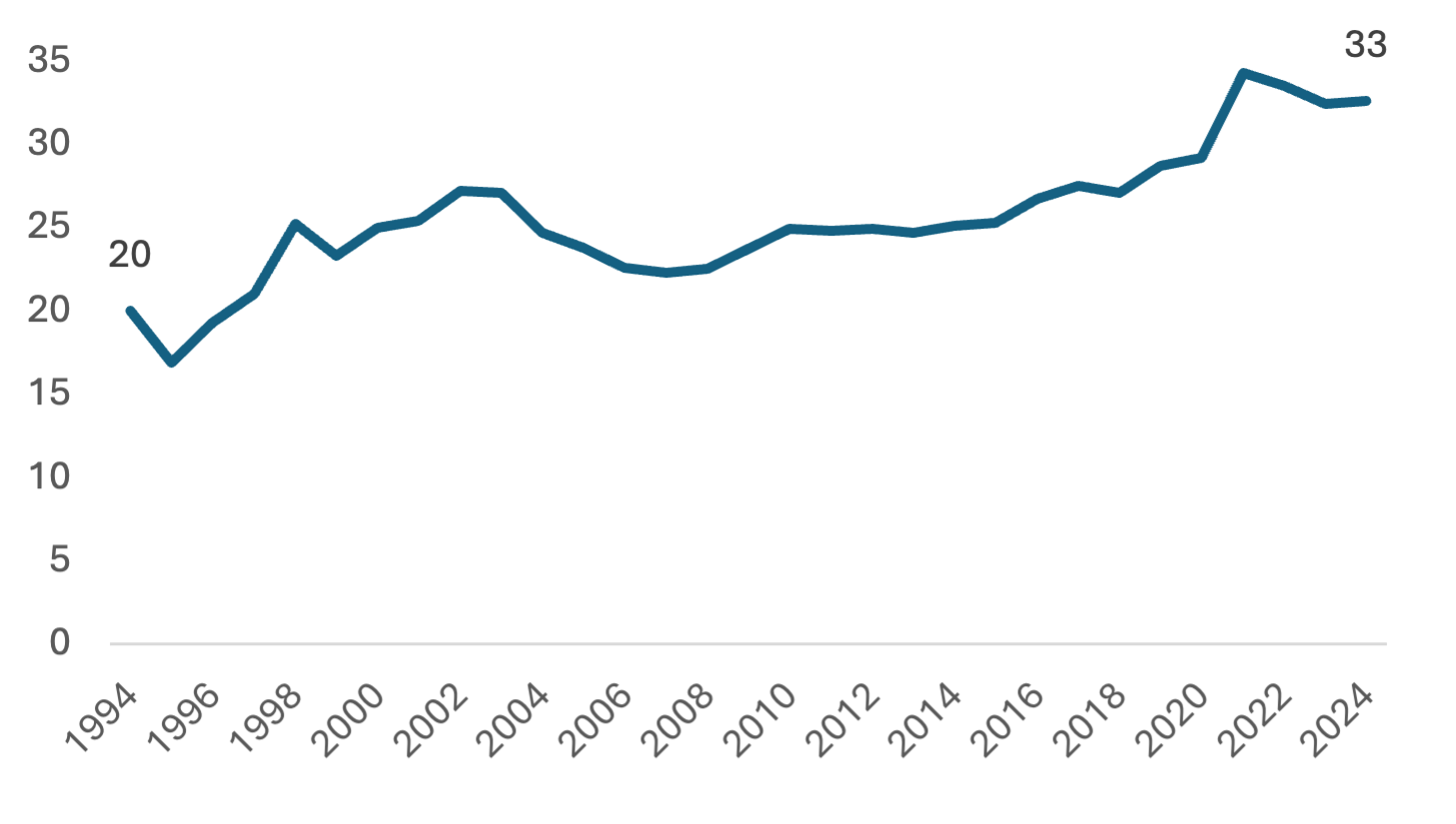

Figure 1: Narrowly defined unemployment percentage rate (i.e., unemployed and seeking work) since the end of apartheid

Source: South African Reserve Bank (SARB)

However, as economic growth picked up, especially after the Emerging Markets crises of 1998, unemployment moderated back to around 22% by 2007. This coincided with growing investment and above 5% GDP growth.

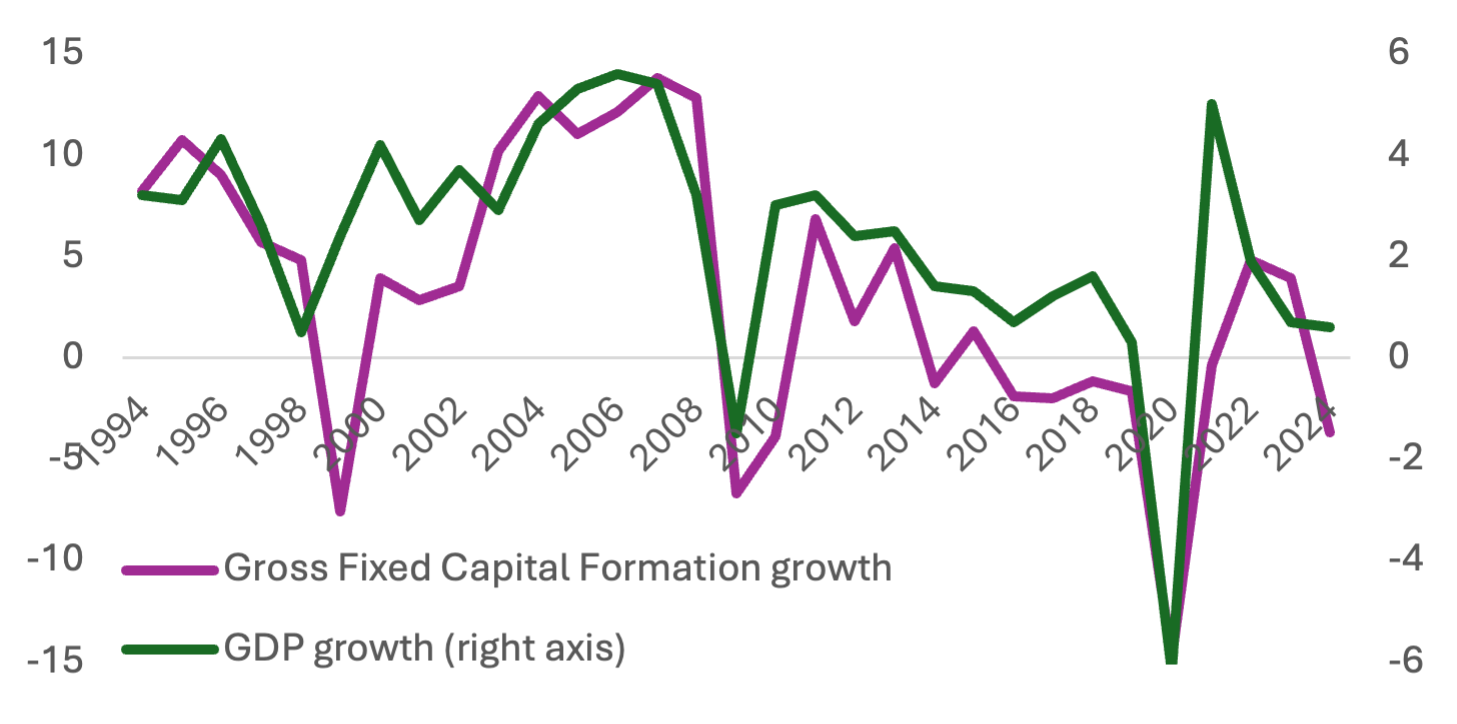

Figure 2: Percentage GDP and Gross Fixed Capital Formation growth since the end of apartheid

Source: South African Reserve Bank (SARB)

The Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative for South Africa (ASGISA) in 2006 attempted to maintain the growth momentum by reforming government services, boosting investment in infrastructure and education to encourage investment. It was less than 2 years before the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 took momentum out of the economy. In 2009, a new president, already suffering under a raft of graft and corruption allegations, largely abandoned the main tenets of the previous President’s policies.

The New Growth Path (2010) and the National Development Plan (2012) failed to move the economic dial. Since then, economic growth has averaged 1.25%. The growing dissonance between those economic plans and growth aspirations, other policies adopted and growing levels of corruption during that period cancelled out the impact of efforts to maintain growth. This is despite the establishment of a bureaucracy to monitor progress, which remains in operation. The National Planning Commission still generates an annual report on the (lack of) progress toward the NDP’s 2030 goals.[3]

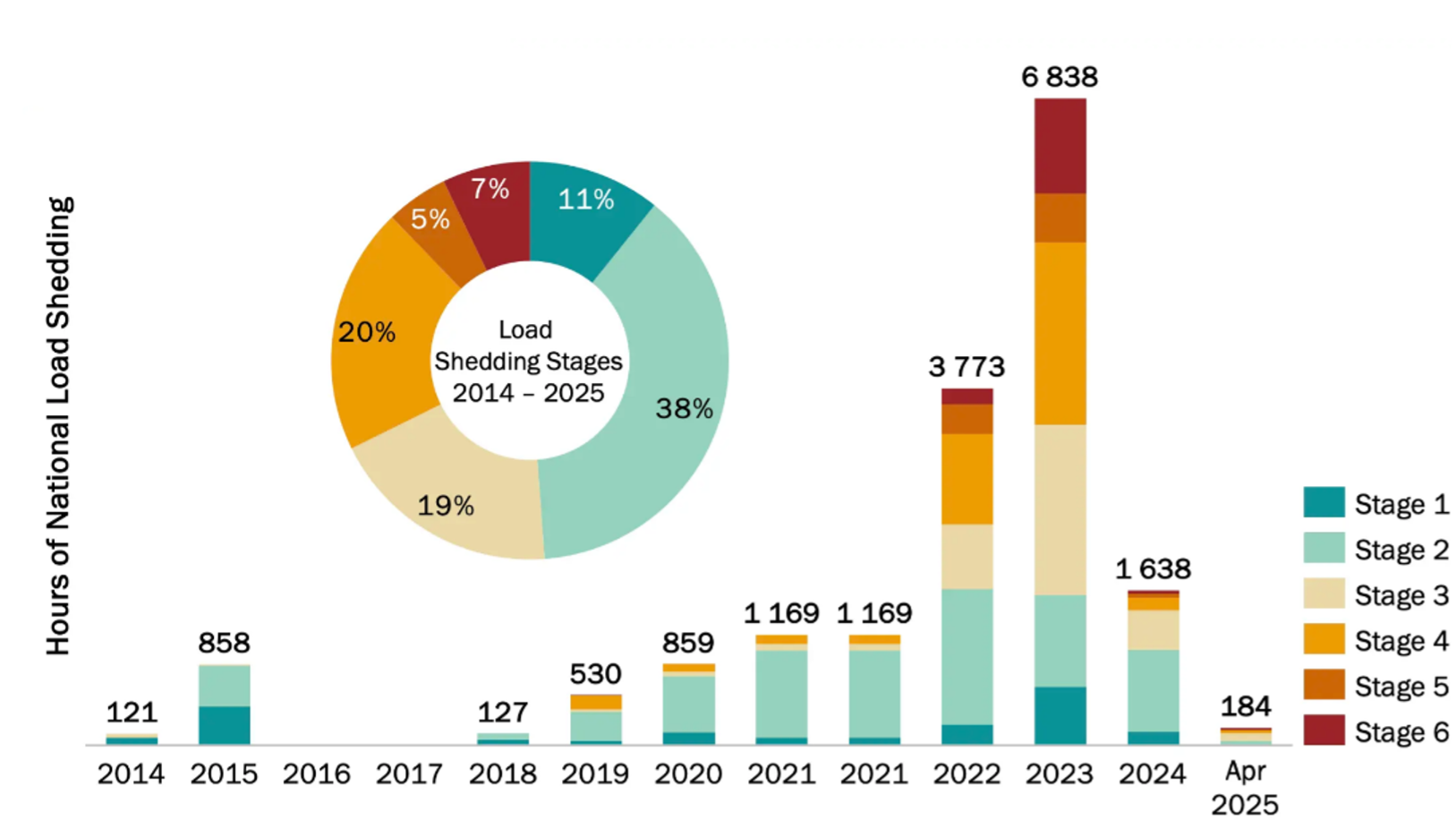

Due to COVID-19, South Africa was not well-positioned to weather the economic shock. Growth has remained tepid, and already stretched government finances were unable to respond to the shock, and business sentiment remained low, coming off a period of optimism coinciding with the replacement of the tainted President with a nominally more business-friendly President in early 2018. Contracting fixed investment from the beginning of the 2010s also had a knock-on impact on enabling infrastructure, especially in the power generation sector, which was controlled by the state. By 2020, blackouts (called load shedding in South Africa) occurred almost 10% of the time. By 2023, blackouts were occurring 78% of the time.

Figure 3: Hours of electricity blackouts by level of blackout per year

Source: Center for Renewable and Sustainable Energy Studies, Stellenbosch University

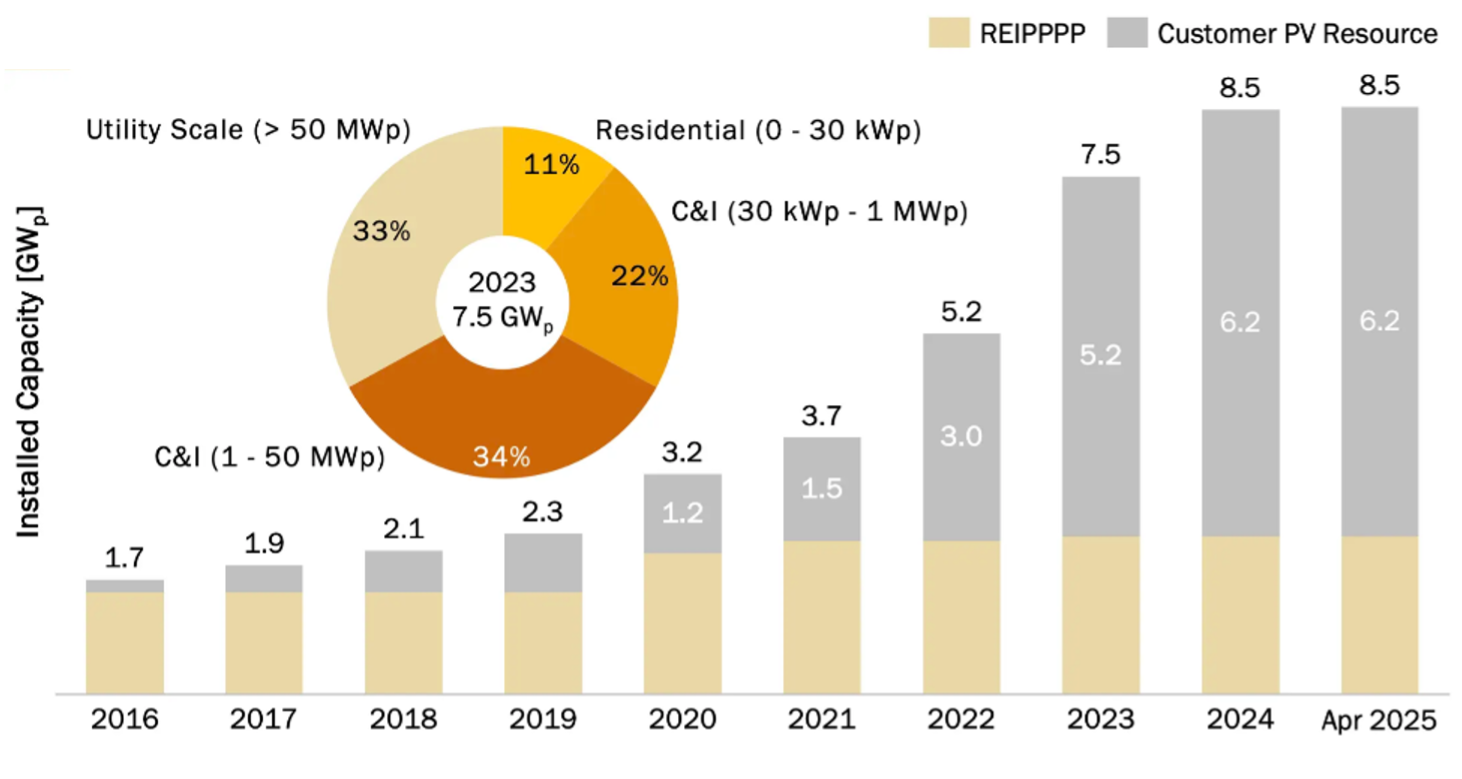

In response to an increasing lack of energy supply and a relaxation of embedded generation licensing requirements, private sector investment in renewable energy boomed, accounting for the majority of Gross Fixed Investment capital growth from 2022 through 2024. Limited fixed investment has gone toward new productive capacity within the economy. As a result, GDP moderated back down to ~1% after recovering from COVID-19 economic shocks.

What is Operation Vulindlela?

A short history of the Office of the Presidency

In 2009, the president introduced two Ministers in the Presidency for National Planning and Performance Monitoring, Evaluation and Administration.[4] Without their own departments, these Ministerial positions provided an opportunity to access individuals who were responsible for leading Departmental Ministries. There are now eight programs under the Office, including Operation Vulindlela.

Operation Vulindlela Phase 1: priorities and results

Operation Vulindlela was launched in October 2020. Like so many previous national development plans, the program focused on unlocking growth by implementing reforms to legislation blocking economic growth opportunities. Unlike other programs, which were big on targets and high-level aspirations, the program was and still is focused mainly on implementing reform at a legal and regulatory level to unlock growth. The expectation is that those reforms would then unlock private investment and a renewed focus on efficient delivery of services, which would be captured under investment and infrastructure development programs.

The most successful example of those reforms was raising the legal limit on private embedded energy generation without requiring regulatory approval.

In a self-assessment of the first phase, the Presidency was positive about the progress made, citing 16 initiatives that were completed and another 4 that were completed but require further activities to unlock value.[5] Commentators have been less effusive,[6] and in the case of private energy generation, revisions to pricing to access utility power are expected to disadvantage embedded energy generators in the near term (especially smaller residential generators), to the benefit of newly created state-owned transmission and distribution operators.[7]

At its heart, the operation has been more successful where interventions have been well defined and interventions require improvements to processing times or relaxation of regulations. In the case of more complex interventions involving large state-owned entities, progress has been slow as a result of the thicket of laws, regulations and standards that impede market liberalization.

Figure 4: Renewable energy capacity by utility scale (REIPP) and embedded generation (Customer PV Resource)

Source: Center for Renewable and Sustainable Energy Studies, Stellenbosch University

For less successful or stalled interventions identified in Phase 1, Phase 2 is expected to continue efforts to address those.

Operation Vulindlela Phase 2: Focus areas

Following on from the momentum created in Phase 1, Phase 2 broadens the range of interventions targeting key supply-side blockers to economic growth, namely:

- Energy sector reforms

- Logistics reforms

- Supply of drinking water

- Reforms to immigration management systems to attract skills and investment

- Improving the delivery of government services, especially at the local government levels where most business services are delivered

- Improving urban centers’ operational efficiency

- Developing digital infrastructure to reduce friction in commerce and increase economic inclusion

Under each initiative are several interventions required to unlock growth.

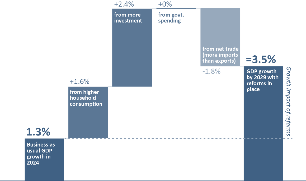

Phase 2 does not provide a deadline against which those activities need to be implemented, but it does provide an estimate of the economic impact of those interventions on growth should they be implemented. At 3.5% by 2029, the modelling suggests that Vulindlela has learned from overambitious growth targets. However, the flip side is that the rate of growth does not begin to address the socio-economic demands of a fast-growing young population that last reduced unemployment when growth averaged more than 5%. At a structural level, Operation Vulindlela struggles to reconcile the same competing issues faced by previous plans, looking to balance the need to encourage private sector development while at the same time adopting an interventionist approach to the delivery of enabling infrastructure.

This is compounded by the fact that Operation Vulindlela is constrained by the state’s inability to swiftly disentangle itself from its service delivery responsibilities while at the same time being constrained in providing the necessary funding to restructure inefficient legacy utilities. A recent example of this was a statement by the Minister of Transport, mandated to privatize rail operations, which highlighted that tendering with private operators would take at least two years to complete, while legislation governing these private sector operators was still to be tabled for debate and passed. This, while the need for increased investment in the national rail company to meet short- and medium-term targets while contracts with the private sector were ironed out, was being partially addressed through fiscal transfers and guarantees.[8] Rating agencies have remained circumspect that these utilities would be able to boost productivity and volumes by stated targets and remain financially unstable in the medium term.[9]

A similar constraint exists in electricity generation as well as bulk and urban water supply. In all, a local bank estimated that infrastructure investment until 2030 would be in the region of $57bn, all coming from the private sector.[10] Given the size of the investment, equivalent to 18.1% of total private and official retirement funds held by South Africans, foreign investors are needed to diversify the investment risk and maintain acceptable costs of capital. The downside to this is that policymakers will need to show economic improvements to foreign investors before foreign funding becomes accessible at affordable rates.

Policymakers are currently trading off the immediate needs to make investments to show improvements can be generated, with the countervailing need to show restraint in public finances to reduce the cost of financing those investments. While the social wage of over 60% of non-interest expenditure (covering costs related to education, healthcare, social protection, community development and employment) suggests that there is room to reprioritize spending toward investment, decades of economic hardship have raised the political cost of reprioritizing social welfare spending to investment. As a result, the current government telegraphed to the market that it will prioritize reducing debt service costs, which reached 16.1% of government expenditure in the tax year 2024/25 and will grow to 16.9% by 2026/27.[11] However, in the yet-to-be-completed 2025/26 budget cycle, National Treasury raised 3-year forecast debt service costs to R1.351 trillion, up from R1.238 trillion in the previous tax year, suggesting these efforts may not be yielding the necessary results fast enough.[12]

Modelling the impact of Vulindlela Phase 2

Modelling institutional reforms to an economy can be imprecise, as the impact of reforms is measured through their second-round impacts on economic activity and GDP growth. Similar reforms undertaken in other markets provide benchmarks that can be used to configure macroeconomic models. However, as is the case with all models, based on other experiences, the likely impacts are not necessarily directly comparable to reforms underway in South Africa.

In the case of Operation Vulindlela Phase 2, the reform impacts were modelled by the Bureau for Economic Research and result in GDP growth expanding to 3.5% per annum by 2029, from a baseline of 1.3% in 2024, led by growth in investment and employment, which translates into higher household consumption expenditure. As South Africa is a relatively small and very open economy, a significant percentage of aggregate demand generated by increased investment and consumption is leaked offshore through increased demand for imports of either capital equipment, business services or goods and services consumed by households. In the modelling undertaken by the BER, state expenditure is modelled to be neutral, i.e., the government is not involved in stimulating economic activity through the way in which it undertakes expenditure, which is unlikely to happen as the government has undertaken a program of fiscal consolidation, likely to result in a negative impact on economic growth.

Figure 5: Modelled impact of Phase 2 reforms on economic growth

Source: Bureau for Economic Research for Operation Vulindlela

How could Phase 2 fall short?

In this environment, Operation Vulindlela Phase 2 appears to fall foul of key constraints:

1) The assumption that the reforms go according to plan is not what has happened in South Africa in the past: South Africa has been a laggard in creating an enabling environment for multi-sector private sector participation in historically state-run industries, as well as throttling private sector activity by overburdening key industries such as mining and manufacturing with regulations. Until now, South Africa applied a case-by-case model to the deregulation of telecoms and energy, which has slowed private sector participation, reduced innovation and limited changes to the market structure.

|

How Phase 1 reforms in electricity generation have not unlocked rapid private sector operation across areas of the national grid Sector regulations remain in a state of flux as ongoing tweaking (such as relaxing size limits for private generation but not setting a common standard to apply net-metering across the national and municipal networks, fragmenting the private sector market opportunity to specific geographical regions where net metering has been enabled) has slowed private sector participation. In recent pricing and billing disputes between public distributors and the national power utility, several capabilities were noted as not being in place, which is likely to exacerbate the current conflicts around debt recoveries and costly legal challenges against a regulator unable to apply its own electricity pricing methodologies. Given the public sector’s limited financial capabilities and the patchwork approach to regulatory reforms, the private sector has not been able to step in to address key bottlenecks such as access to transmission infrastructure for wheeling or providing a net metering solution to private sector generators and consumers or creating a standard to access publicly owned land (such as schools) for energy generation. In the case where private participation did occur, the state has attempted to expel the private sector operator, even though the operator was delivering a service that was superior to the one it replaced from both a financial sustainability as well as service provision perspective. |

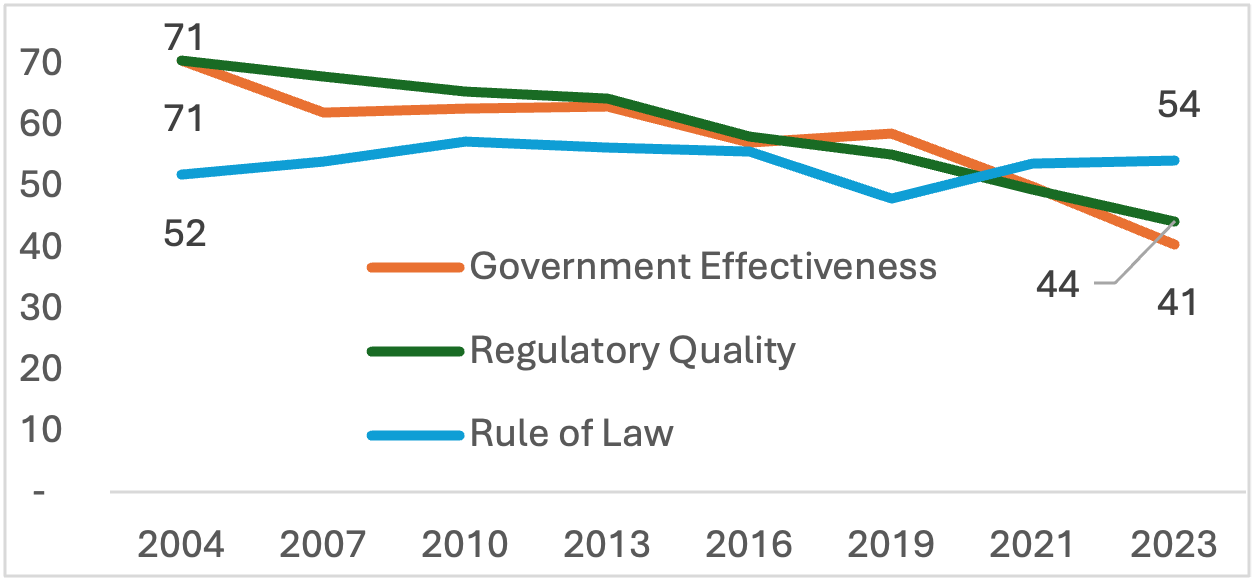

2) Regulator capabilities will be new and/or severely constrained in their ability to manage the private sector: In a recent review of the politicization of the state bureaucracy in South Africa and of the regulatory frameworks applied to the liquid fuels spaces, South Africa’s weak bureaucracy and poor regulatory choices are discussed.[13]

|

Understanding South Africa’s declining governance and regulator scores Since the end of apartheid, South Africa’s bureaucracy has been hollowed out and politicized as incoming political leadership attempted to bypass a bureaucracy hired by the previous apartheid government, which had been guaranteed employment until 1999. This creation of a parallel bureaucracy loyal to the ANC was not selected on merit but rather on loyalty and perceived competency. As a result, Government effectiveness and regulatory quality scores have declined. In contrast, the more independently administered legal system has been relatively less impacted, with scores increasing marginally since 2004. Figure 6: World Governance Effectiveness percentile ranking

Source: World Bank |

For economic sectors that lend themselves to economic utilities with declining marginal costs of delivery and high upfront investment requirements, strong and capable regulators are key in managing powerful private businesses incentivized through a profit motive to generate efficiencies, price out competition and gain market share.

In the case of South Africa, the current regulatory regime remains weak and moves to professionalize senior leadership in the public sector have only just begun. Unfortunately for South Africa, regulatory credibility is generated over time and involves ongoing investment in the regulator’s powers, regulatory framework and regulations to finesse the strategic objectives of the regulator, which can also change over time. Concerns over regulator effectiveness are likely to place a drag on private investment as well as investor confidence, resulting in either delays, higher costs of capital (to mitigate perceived investment risks), and/or investors prioritizing short-term financial targets at the expense of long-term infrastructure investments, at least in the first few years of operation.

3) Balancing private sector buyer attractiveness with the need to repay public debts, retain existing employees and include local minority investors: State-run utilities in the energy and transportation sector currently do not meet acceptable financial sustainability standards on a stand-alone basis. This has required the state to step in and provide government guarantees and capital injections to offset losses. It also means that, should all or portions of those entities be privatized, the state would incur investment or cash-flow losses on their investments. On the other side, prospective private sector operators are likely to find state-owned public-sector assets to be unattractive investment prospects without significant restructuring and new investment.

Current concessioning terms applied to recent port concessions at Durban port suggest there are strict limits to how much restructuring is allowed, including limits to retrenching existing staff and requirements to include local investment partners with limited expertise in boosting efficiencies (in the case of the Durban concession, it is the existing state-owned operator).[14] Reducing flexibility in operations and investment has negative implications for private sector operators. This is likely to delay how investment and reforms are undertaken by new operators, as well as increase the risk that the concession fails to deliver the expected operational improvements necessary to drive GDP growth.

4) A history of anti-competitive activities by recently privatized state businesses risks slowing the impact of private capital: Privatization of state-controlled utilities is not new to South Africa. South Africa’s isolationist past under apartheid is a case study in state-led industrialization across iron and steel, petroleum, telecommunications, defense manufacturing, electricity generation, transportation and logistics. Thus far, iron and steel, petroleum products and telecommunications are notable case studies of privatizations for South African policymakers. In all three cases, ex-state-owned entities have engaged in aggressive anti-competitive behavior once privatized, resulting in decade-long struggles by the South African Competition Commission to enforce a level playing field in those sectors.

While that behavior has not been unique to ex-state-owned entities, the utility-like structure of those operators when privatized has generated significant costs for their consumers, price gouging, limited competition and innovation around product delivery and most importantly, regulatory capture.[15] This is likely to slow the impact that efficiencies could bring if a more competitive market were enforced from day one.

5) 3 tiers of executive government with overlapping mandates will slow implementation and increase conflict in a multi-party-controlled executive branch: South Africa’s constitution makes specific reference to spheres of executive government, which, while federalist in nature (i.e., distinctive), are required to be “interdependent and interrelated”[16] in a framework described as co-operative governance. Given the country’s past and its economic and demographic size and complexity, it is understandable that the Executive was divided amongst three layers of government, which were required to co-operate with one another. However, this delegation of responsibility, with in most cases a shared responsibility to deliver services between at least two layers of Executive government, has created a complex web of cross-coordination between the various layers. It also belies the fact that municipal constitutional responsibilities are estimated to deliver 46% of the constitutional functions of the state.[17] While this system may have worked in an environment where all layers of government were controlled by one party or coalition, South Africa’s recent political results suggest that the executive at each of the three layers of government is increasingly operated by competing parties from across the political spectrum. This has created conflicts between various layers of government, especially in the delivery of utility services, including electricity, water and transportation infrastructure.

Vulindlela is a perfect example of the national government intervening in provincial and local government constitutionally mandated spheres. Of the 7 focus areas, the vast majority encompass economic sectors that have been delegated to either provincial or municipal governments, including energy sector reforms, access to drinking water, improving delivery of government services, especially at local government levels where most business services are delivered, improving urban centers operational efficiency and developing digital infrastructure to reduce friction in commerce and increase economic inclusion. The result is that:

- Reforms are increasingly likely to be subject to legal challenges that require supermajorities to solve, which is unlikely to happen easily given the current party political divide at a national level.

- Coordination between spheres of government is likely to slow any wholesale reforms of a uniform structure. Compromises undertaken between different political parties at different levels of government are also likely to drive a range of temporary reforms that meet the requirements of negotiating spheres of government at a particular point in time.

- Private sector operators contracting with the government are increasingly at risk of being dragged into the sphere of government turf wars or being subject to re-contracting when political dynamics change.

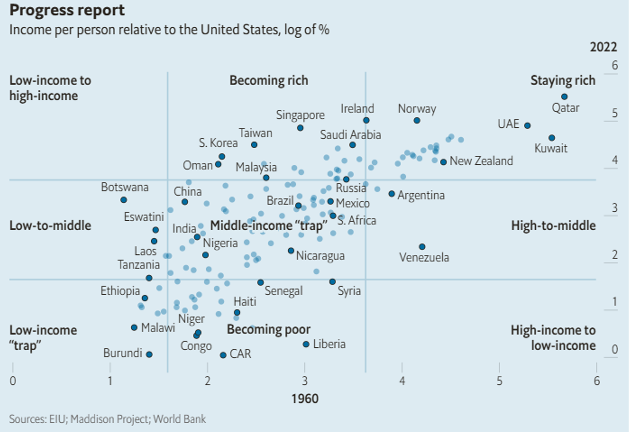

Can Vulindlela help South Africa exit upper middle-income status?

Vulindlela’s priority focus on reforms to the delivery of enabling infrastructure and government is insufficient to raise economic growth sufficiently to exit middle-income status within the next decade or two. While the program is laudable, especially in an economy that has suffered the consequences of regressing “service delivery,” it does not address key economic and structural constraints to South Africa’s middle-income economy that could allow it to exit the so-called middle-income trap.

Figure 7: Log of percentage income per person compared with the USA[18]

Source: EIU, Maddison project, World Bank

To achieve high-income status, South Africa would need to prioritize skills-intensive manufacturing and services that would help drive an improvement in its terms of trade. In the 2017 study by the Asian Development Bank Institute on likely drivers of success in exiting middle-income status,[19] the following indicators were stronger predictors of whether a country would reach high-income status between 1960 and 2009:

- A history of strong growth underpinned by

- A high share of industrial output to GDP (at the expense of both agriculture and, especially for middle-income countries, services)

- High rates of openness to trade

- Low levels of income inequality

A review of Vulindlela’s priorities suggests South Africa is addressing one of the three key drivers of GDP per capita growth, boosting openness to trade. It could be argued that reforms to the delivery of enabling utility services would have a knock-on effect on the ability to industrialize and improve employment prospects. However, at 3.5% growth, employment prospects are likely to remain constrained, resulting in limited progress in reducing South Africa’s very high levels of income inequality. Phase 2 priorities also include targets that could explicitly be counter to growth enablers, including a focus on boosting tourism (a service).

This implies that while Vulindlela Phase 2 is likely to address key enabling capabilities of the state and the economy to drive growth, the program is not sufficient to deliver an exit from middle-income status on its own.

Figure 8: GDP per capita (in a real local currency unit) and annual growth

Source: World Bank

Conclusion

South Africa’s experience of national economic programs can be best summed up as recurring disappointments. Over 30 years since the end of apartheid, and five national economic development programs later, South Africa’s economic prospects have regressed, with the last 15 years experiencing falling real GDP per capita. Vulindlela Phase 2 is an attempt to arrest that decline. While necessary, based on previous programs and the relatively low GDP growth targets it is aiming for, the program is unlikely to launch South Africa on a growth path out of middle-income status in the foreseeable future. It will be lucky to stabilize the economy’s decline.

When adding the significant bureaucratic hurdles to be overcome to reach Phase 2 goals, the prospects of success dim further. South Africa’s multi-tiered executive branch, predisposed to driving conflict should political parties not be aligned, combined with a politicized and increasingly ineffectual bureaucracy, does not position the state well to enable the private sector to take over the delivery of key enabling services (electricity, water, transportation) or regulate these newly privatized services effectively.

Fundamentally, the program is not well aligned to key determinants of long-run economic growth that are necessary but not sufficient determinants of reaching high-income status, especially a growth-at-all-costs mentality, which is the key determinant of successful newly minted high-income countries. For a country that was within touching distance of high-income status, that is a disappointment.

[1] David Nyadzani Mamburu, “The Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) and the Poverty Relief Programme (PRP),” University of Pretoria, University of Pretoria (2004), https://repository.up.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/d16f6845-c491-40a3-85c7-e2305cb7dd81/content http://krepublishers.com/02-Journals/JHE/JHE-49-0-000-15-Web/JHE-49-3-000-15-Abst-PDF/JHE-49-3-245-15-2612-Kangethe-S-M/JHE-49-3-245-15-2612-Kangethe-S-M-tx[8].pdf.

[2] Johannes Fedderke, A CASE OF POLARIZATION PARALYSIS: the debate surrounding a growth strategy for South Africa (n.d.), https://econrsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/pp01_interest.pdf

[3]https://www.nationalplanningcommission.org.za/assets/Documents/Report%20on%20Monitoring%20National%20Development%20Plan%20Indicators%20and%20Targets__December%202024.pdf.

[4] South African Government, “Statement by President Jacob Zuma on the appointment of the new Cabinet,” May 10, 2009, https://www.gov.za/news/speeches/statement-president-jacob-zuma-appointment-new-cabinet-10-may-2009?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

[5] National Treasury, Republic of South Africa, “Operation Vulindlela: Phase 1 Review: Reflecting on Progress in Driving South Africa’s Economic Reform Programme,” (2020-2024), https://www.stateofthenation.gov.za/assets/downloads/Operation_Vulindlela_Phase_1_Review.pdf.

[6] Roy Havemann and Nomvuyo Guma, “Planting the seeds of future prosperity Phase 2 of Operation Vulindlela is the glue that binds the GNU together,” Business Day, May 9, 2025, https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/2025-05-09-roy-havemann-and-nomvuyo-guma-planting-the-seeds-of-future-prosperity/

[7] “South Africans using electricity are about to get a huge shock,” Business Tech, March 3, 2025, https://businesstech.co.za/news/energy/814911/south-africans-using-electricity-are-in-for-a-huge-price-shock/.

[8] “BFI funding crucial for unlocking short-term freight investments while long-gestation private projects evolve,” Engineering News, June 24, 2025, https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/bfi-funding-crucial-for-unlocking-short-term-freight-investments-while-long-gestation-private-projects-evolve-2025-06-24.; “Transnet seeks urgent funding to address South Africa’s rail infrastructure challenges – Creecy,” IOL, June 24, 2025, https://iol.co.za/business-report/companies/2025-06-24-transnet-seeks-urgent-funding-to-address-south-africas-rail-infrastructure-challenges-creecy/#google_vignette.

[9] “S&P says Transnet will burn cash until 2028,” Business Day, July 15, 2025, https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/national/2025-07-15-sp-says-transnet-will-burn-cash-until-2028/.

[10] “South Africa Moves Closer to Traded Power Market,” RMB, April 14, 2025, https://www.rmb.co.za/news/south-africa-moves-closer-to-traded-power-market.

[11]https://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2024/ene/FullENE.pdf.

[12] National Treasury, Republic of South Africa, “Budget,” May 21, 2025, https://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/National%20Budget/2025May/review/May%202025%20Budget%20Overview.pdf.

[13] Ivor Chipkin, “Why has state capture in South Africa, unlike in China, not lead to growth and development?,” Government and Public Policy Think Tank (GAPP) 2022, https://www.gtac.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Why-has-state-capture-in-South-Africa-unlike-in-China-not-lead-to-growth-and-development1_New-Agenda_Ivor-Chipkin.pdf.; Motshegetsi Sebalo, Economic regulations and the effectiveness of South Africa’s the liquid fuels price regulatory framework, Minor Dissertation, University of Johannesburg (2021), https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/view/pdfCoverPage?instCode=27UOJ_INST&filePid=136339900007691&download=true.

[14] Eugene Goddard, “Transnet takes a hard line about concessionary involvement at DCT,” Freight News, June 28, 2024,https://www.freightnews.co.za/article/transnet-takes-a-hard-line-about-concessionary-involvement-at-dct.; “Unions hail Durban port decision,” Business Live, October 13, 2024, https://www.businesslive.co.za/bt/business-and-economy/2024-10-13-unions-hail-durban-port-decision/.

[15] Ewan Sutherland, “Telecommunications in South Africa: enforcement of competition,” The Competition Commission, 2021, https://www.compcom.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Telecommunications-in-South-Africa_enforcement-of-competition.pdf.

[16] The SA Constitution, “CHAPTER 3: Co-operative Government,” (n.d.), https://www.justice.gov.za/constitution/SAConstitution-web-eng-03.pdf.

[17] “Action needed to fix local government,” Business Day, April 16, 2025, https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/editorials/2025-04-16-editorial-action-needed-to-fix-local-government/.

[18] “Which countries have escaped the middle-income trap?,” The Economist, March 30, 2023, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/03/30/which-countries-have-escaped-the-middle-income-trap.

[19] David Bulman, Maya Eden, and Ha Nguyen, “TRANSITIONING FROM LOW-INCOME GROWTH TO HIGH-INCOME GROWTH: IS THERE A MIDDLE-INCOME TRAP?,” ADB Institute, January 2017, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/224601/adbi-wp646.pdf.