Latin America is not a single entity as we are talking about 12 countries in South America and 21 countries in Central America and the Caribbean, which range from influential countries like Brazil (the ninth-largest economy in the world, according to the World Bank) to small states like Costa Rica. Nor is there any ideological or political unity, as these have different regimes in terms of their institutions, tendencies and preferences. For this reason, this insight will focus on three countries in the region that are members of the G-20: Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. This is a reductionist approach, but given the specific weight of these three countries, they are representative of the region.

The study analyzes the different levels of relations (political, commercial, financial) in order to understand the limits, but also the opportunities, of developing relations between Latin America and the GCC, which could be extremely positive for all the actors involved. It is essential to go beyond simplistic and superficial visions based on general considerations to understand the pitfalls that limit the deepening of relations and to propose concrete measures that could help to overcome them.

An important part of the assessment is to understand the structural constraints of countries in both regions, which do not make the Arab Gulf countries the only priority for Latin American countries, nor Latin American countries the only priority for Arab Gulf countries. This does not mean, however, that there are not important mutual benefits to be gained from seizing opportunities to improve their relations. It is necessary not only to overcome this simplistic view but also to avoid seeing these countries as potential markets due to logistical constraints and to come up with innovative ideas regarding trade opportunities, focusing on technology-intensive areas based on joint ventures in research and development.

Areas of linkages between the GCC and Latin America

One of the key points in analyzing relations between Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil and Mexico) and the GCC is to be aware of the geographical and cultural (especially linguistic and religious) distance between the two regions. This does not mean that these differences cannot be overcome, but it is important to recognize them.

Immigration of Arab-origin people to Latin American countries has been important in terms of numbers, but it is a social group that originated in what is now Lebanon and Syria, that is essentially Christian (Maronite or Orthodox), and that, as a result of the assimilation and integration policies of the countries of the region, has lost the use of the Arabic language and maintains only superficial relations with its places of origin. This is understandable, given that most of these immigrants arrived in Latin America almost a century ago.

To this distance must be added the existence of simplifications and stereotypes, as well as the scant development of Middle Eastern studies in the countries analyzed, resulting in a poorly detailed vision of the realities of the GCC countries.

This starting point, which is not insurmountable but relevant, must be considered when it comes to understanding expectations and identifying existing opportunities in the Arab Gulf countries. It is noteworthy that Latin American countries have begun a process of diversifying their relations, giving priority to other regions and countries, particularly countries such as China and sub-Saharan Africa.

Initiatives such as Brazil’s in 2005, the ASPA (South America-Arab Countries) forum, which brought together the 12 countries of South America (excluding Mexico, of course) and the 22 countries of the League of Arab States, were very positive, although the processes of instability in some Arab countries from 2011 onwards, known as the so-called “Arab Spring”, and regional tensions in South America have interrupted this process.

Today there are other multilateral bodies that link the two regions, such as OPEC (although none of the three Latin American countries analyzed here are members, but Mexico is part of the group known as OPEC+), the Forum of Gas Exporting Countries (although none of the three Latin American countries analyzed here are members, but Venezuela and Bolivia are), [i] the G-20 (of which the only GCC country that is a member is Saudi Arabia, in addition to Argentina, Brazil and Mexico) and the BRICS Forum (which now includes Brazil and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and to which Saudi Arabia has been invited but has not formalized its acceptance, as has Argentina, which has been invited but has declined to join).[ii] Another regional organization, MERCOSUR (Mercado Común del Sur, in Spanish, or Southern Common Market, in English), which includes Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay (and Venezuela, although its membership is currently suspended), is negotiating a free trade agreement with the UAE.[iii]

Diplomatic relations

Latin American countries maintain full diplomatic relations with the GCC countries, although until well into the 1990s the relationship had little substance and was more protocol than reality. Today, political relations have deepened, without there being any sensitive issues that alienate the two. Indeed, in the Lima Declaration of the ASPA Summit, Latin American countries supported the UAE in its initiative to find a peaceful solution to the issue of the UAE islands occupied by Iran.[iv] The deepening of relations is reflected in the number of high-level visits (heads of state and government, foreign ministers) and the existence of permanent diplomatic missions.

Table 1: Resident embassies of Latin American G-20 countries in the GCC

| Saudi Arabia | Bahrain[v] | UAE | Kuwait[vi] | Oman | Qatar | |

| Argentina[vii] | X[viii] | Concurrent from Saudi Arabia | X[ix] | X | Concurrent from Saudi Arabia | X[x] |

| Brazil[xi] | X[xii] | X | X[xiii] | X[xiv] | X[xv] | X[xvi] |

| Mexico[xvii] | X[xviii] | Concurrent from Saudi Arabia | X[xix] | X[xx] | Concurrent from Saudi Arabia | X[xxi] |

Table 2: Resident embassies of GCC countries in Latin American G-20 countries

| Argentina[xxii] | Brazil[xxiii] | Mexico | |

| Saudi Arabia | X | X | X |

| Bahrain | X[xxiv] | ||

| UAE[xxv] | X[xxvi] | X[xxvii] | X[xxviii] |

| Kuwait[xxix] | X | X | X |

| Oman[xxx] | Concurrent from Brazil | X | Honorary Consulate |

| Qatar | X[xxxi] | X[xxxii] | X[xxxiii] |

Relations between the GCC countries and the three Latin American countries analyzed are based on bilateral ties, and the existence of permanent diplomatic missions is an advantage for Brazil, which is the only country in the region to maintain embassies in all six GCC countries. Argentina and Mexico, on the other hand, have embassies in only four of these countries: Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, and Qatar. It is the same four Arab countries that have resident embassies in the three Latin American countries analyzed. It could therefore be argued that these GCC partners have the greatest interest and resources in engaging with the Latin American region.

The GCC as trading partners

Trade statistics show that trade links between these groups of countries are marginal in terms of their external trade. Whether one looks at data from the Latin American Integration Association (LAIA) or the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), where there are some differences, the trends are the same.

For Brazil,[xxxiv] the GCC countries account for less than 3% of its exports (according to the OEC’s 2022 statistics): the UAE 0.98% (US$3.3 billion), Saudi Arabia 0.86% (US$2.92 billion), Bahrain 0.42% (US$1.43 billion), Oman 0.31% (US$1.05 billion), Qatar 0.12% (US$420 million) and Kuwait 0.10% (US$347 million). The vast majority of these are primary products such as commodities.

The situation is similar for Argentina:[xxxv] Saudi Arabia accounts for 1.20% of its exports (US$1.05 billion), the UAE for 0.38% (US$328 million), Oman for 0.23% (US$198 million), Kuwait for 0.12% (US$104 million), Qatar for 0.056% and Bahrain for 0.015%.

Data for Mexico’s exports show similar rates:[xxxvi] UAE 0.21% (US$1.14 billion) of total exports, Kuwait 0.13% (US$734 million), Qatar 0.038% and Saudi Arabia 0.012%.

The region’s markets are also not very important for the UAE:[xxxvii] Brazil 0.72% (US$2.88 billion) of its total exports, Argentina 0.22% (US$902 million) and Mexico 0.12% (US$469 million).

For Saudi Arabia,[xxxviii] the statistics confirm the low percentage, hence importance, of the region’s markets in its total exports: Brazil 1.32% (US$4.78 billion) and Argentina 0.27% (US$966 million).

For Kuwait,[xxxix] Brazil represents 0.31% of its exports (US$319 million) and Argentina 0.070% (US$71 million).

In the case of Oman,[xl] Brazil represents 0.97% (US$738 million), Mexico 0.16% (US$125 million) and Argentina 0.14% (US$105 million).

Data for Bahrain[xli] show that Mexico accounts for 1.38% (US$286 million) of its exports, Brazil for 0.87% (US$180 million) and Argentina for 0.31% (US$63 million).

Finally, Brazil represents 0.95% (US$1.13 billion) of Qatar’s exports,[xlii] Argentina 0.098% (US$116 million) and Mexico 0.089% (US$106 million).

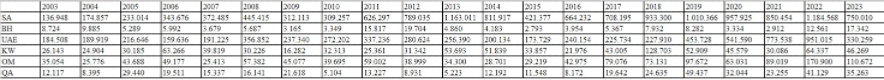

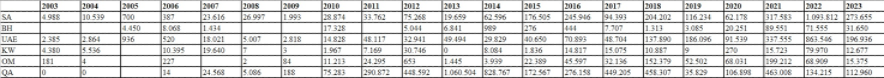

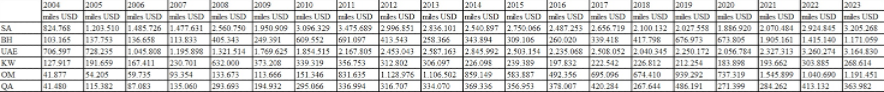

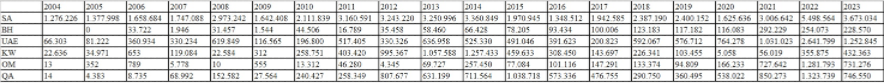

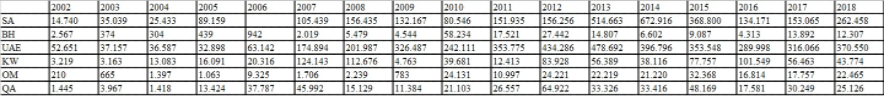

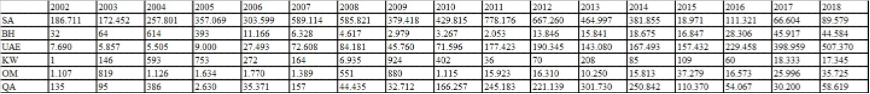

Table 3 below shows the values in thousands of dollars over the last few years, which also underlines the marginal importance of trade relations for Latin American countries.

In conclusion, despite the political will, there are structural constraints that are difficult to change: distance and the logistical costs involved, as well as the will of the GCC countries to implement food security strategies that could reduce imports of this type of product from Latin America in the future.

Table 3: Trade statistics[xliii]

Exports from Argentina to the Gulf States (in thousands of USD)

Imports of Argentina from Arab Gulf countries (in thousands of USD)

Exports from Brazil to the Gulf States (in thousands of USD)

Imports of Brazil from Arab Gulf countries (in thousands of USD)

Exports from Mexico to Arab Gulf countries (data to 2018) (in thousands of USD)

Imports of Mexico from Arab Gulf countries (data until 2018) (in thousands of USD)

The GCC as a logistical hub for Latin America

One of the ideas often repeated by Latin American countries is the importance of the Arab Gulf countries not only as markets for their products but also as “hubs” that would allow the re-export of Latin American products to other markets of interest and close to the Gulf, particularly India.

While this is a possibility, it should be noted that many other elements are needed for this to happen. Among these are the greater frequency and options for direct maritime lines between Latin American ports and those in the Gulf. It is a case of “Which comes first, the chicken or the egg” type question. In other words, the question boils down to whether there is low frequency because of little cargo to carry, or little cargo to carry because there is low frequency. The answer is simple: carriers will not offer more services if they cannot first secure cargo volumes in the medium term. Therefore, creating a critical mass of trade, i.e., demand and supply at both ends, is the first step to increasing the provision of such shipping services.

On the other hand, to generate such trade links, it is necessary to promote business contacts and meetings. In this respect, the existence of direct flights and visa-free regimes are essential elements. The UAE’s Emirates Airlines, for instance, flies from Buenos Aires/Rio de Janeiro/Mexico City to Dubai and from there to other airports in the Gulf. On the other hand, Qatar Airways flies from Buenos Aires/Sao Paulo to Doha and from there to other airports in the Gulf. Finally, Turkish Airlines offers flights from Buenos Aires/Sao Paulo/Mexico City to various airports in the Arab Gulf via Istanbul Airport.

In terms of visa regimes, the situation is as follows:

Table 4: Visas requested by GCC countries for Latin American citizens

| Saudi Arabia[xliv] | Bahrain[xlv] | UAE[xlvi] | Kuwait[xlvii] | Oman[xlviii] | Qatar[xlix] | |

| Argentina | X[l] | X[li] | X[lii] | X | X[liii] | X[liv] |

| Brazil | X[lv] | X[lvi] | X[lvii] | X | X[lviii] | X[lix] |

| Mexico | X[lx] | X[lxi] | X[lxii] | X | X[lxiii] | X[lxiv] |

Although Table 4 above shows that all Gulf countries require visas for citizens of Argentina, Brazil and Mexico, in practice the UAE and Qatar issue visas on arrival. Bahrain and Oman allow electronic or on-arrival visas. Only Saudi Arabia and Kuwait require visa applications to be processed in advance.

Table 5: Visas requested by Latin American countries for citizens of the Arab Gulf States

| Argentina[lxv] | Brazil[lxvi] | Mexico[lxvii] | |

| Saudi Arabia | X[lxviii] | X | X |

| Bahrain | X[lxix] | X | X |

| UAE | |||

| Kuwait | X | X | |

| Oman | X[lxx] | X | |

| Qatar | X |

Table 5 above shows that Mexico is the most restrictive country for citizens of the Arab Gulf States, requiring visas for all except Emirati citizens. This is followed by Argentina, which allows visa-free entry for Emirati and Qatari citizens and makes exceptions for citizens of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Oman who hold U.S. visas. Only Kuwaiti citizens require visas. Finally, Brazil is the least restrictive country, requiring visas only for citizens of Saudi Arabia and Bahrain.

According to these two tables, Latin American countries tend to be more restrictive than Arab countries regarding visas, especially for tourism and business visits. Any visa waiver initiative would have a positive impact by encouraging tourism and business travel.

For the Arab Gulf countries to become re-export hubs for Latin American products, a higher volume of businesses would require more frequent shipping and greater openness, particularly on the part of Latin American countries, regarding visa waiver regimes. This could lay the foundations for greater trade and increase the number of companies from both regions linking up commercially.

The GCC as a source of investment

When we think of the wealth of the GCC countries, we tend to think of them as sources of investment, but we must recognize that when we talk about investment, we must bear in mind that these are complex processes that fundamentally require legal schemes that favor and protect them. Latin American countries have implemented the following investment regimes with respect to the Arab Gulf countries:

Table 6: Investment protection agreements

| Saudi Arabia | Bahrain | UAE | Kuwait | Oman | Qatar | |

| Argentina | X | X | ||||

| Brazil | X[lxxi] | |||||

| Mexico | X | X[lxxii] | X |

Argentina signed an investment protection agreement with the UAE (signed in 2018 and approved in 2024) and Qatar (signed in 2016 and approved in 2018), while it has only an investment promotion agreement with Saudi Arabia (signed in 2023 and entered into force in 2024). Brazil only has an agreement with the UAE (signed in 2019 and approved in 2023). Mexico has an agreement with the UAE (signed in 2016 and approved in 2018), with Bahrain (signed in 2012 and approved in 2014) and with Kuwait (signed in 2013 and approved in 2016). Mexico is the country that offers the most protection to investments from the Gulf states.

Beyond this general outline, there are macroeconomic variables and opportunities that need to be taken into account. The instability and problems of Latin American countries are therefore difficult hurdles to overcome. This explains why the activities of sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) in the region are still limited,[lxxiii] even though concrete opportunities exist. So far, the only operations in the region are those of the Emirati sovereign wealth fund Mubadala and the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) in Brazil, as well as those of the Emirati company DP World in port infrastructure in several countries in the region.

However, links in this area are still underdeveloped and sectoral. Political support manifested in the signing of investment protection agreements needs to be matched by positive macroeconomic performance for such investment flows to develop. Opportunities are there, but much remains to be done.

GCC countries as Research & Development (R&D) partners

A yet unexplored case could be a key vector for the development of relations between the two groups of countries. This is to go beyond the traditional vision of “seeking” markets for mostly primary products that the countries sell and to broaden the framework to prioritize opportunities for R&D cooperation in technology-intensive sectors. This would have multiple benefits: it would diversify trade relations by moving away from a matrix centered on low value-added primary products (commodities).

It would contribute to the objectives of the development and economic diversification strategies being implemented by the GCC countries. It would also have a multiplier effect on other technology-intensive sectors through the creation of working groups and the joint development of human resources. That would then provide a new axis for linking the countries of the global South in an area of strategic importance. What the UAE’s EDGE Group has done in the defense industry in Brazil[lxxiv] is an example of what can be done in this area.

Conclusion

The relationships between the GCC countries and the three Latin American countries show that there are limits, but that if new schemes are considered, they could be developed significantly. Without neglecting attempts to expand traditional trade links, new options should be considered, such as technology-intensive areas of cooperation, where R&D partners rather than buyers of products should be sought. The combination of financial capabilities, human resources, and geographical location of both regions, coupled with the absence of current and past conflicts or tensions, can provide the framework for a promising and beneficial future for all concerned.

[i] “GECF Country List,” Gas Exporting Countries Forum, https://www.gecf.org/countries/country-list.aspx.

[ii] Paulo Botta, “Argentina and BRICS,” TRENDS Research & Advisory, December 1, 2024, https://trendsresearch.org/insight/argentina-and-brics/.

[iii] https://www.escenariomundial.com/2024/11/17/mercosur-y-emiratos-arabes-unidos-avanzan-hacia-un-acuerdo-de-libre-comercio/.

[iv] https://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/10915/44291/ASPA-_Declaraci%C3%B3n_de_Lima__octubre_2012__38_p._.pdf.

[v] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Bahrain, “Foreign Missions Accreditated to Bahrain,” https://www.mofa.gov.bh/en/foreign-missions-and-accredited-organizations.

[vi] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, State of Kuwait, Foreign Diplomatic Accreditated Missions in the State of Kuwait, https://www.mofa.gov.kw/en/kuwait-missions/foreign-diplomatic-missions/.

[vii] https://www.cancilleria.gob.ar/es/representaciones.

[viii] https://earab.cancilleria.gob.ar/.

[ix] https://eearb.cancilleria.gob.ar/

[x] https://eqatr.cancilleria.gob.ar/

[xi] https://www.gov.br/mre/pt-br/assuntos/Embaixadas-Consulados-Missoes/do-brasil-no-exterior.

[xii] https://www.gov.br/mre/pt-br/embaixada-riade.

[xiii] https://www.gov.br/mre/pt-br/embaixada-abu-dhabi.

[xiv] https://www.gov.br/mre/pt-br/embaixada-kuaite.

[xv] https://www.gov.br/mre/pt-br/embaixada-mascate.

[xvi] https://www.gov.br/mre/pt-br/embaixada-doha.

[xvii] https://portales.sre.gob.mx/directorio/embajadas-de-mexico-en-el-exterior.

[xviii] https://embamex.sre.gob.mx/arabiasaudita/index.php/es/.

[xix] https://embamex.sre.gob.mx/emiratosarabesunidos/.

[xx] https://embamex.sre.gob.mx/kuwait/index.php/es/.

[xxi] https://embamex.sre.gob.mx/qatar/es/.

[xxii] https://www.cancilleria.gob.ar/representaciones-extranjeras.

[xxiii] https://www.gov.br/mre/pt-br/assuntos/Embaixadas-Consulados-Missoes/de-outros-paises-no-brasil.

[xxiv] Embassy of the Kingdom of Bahrain, Brasilia, “Solidifying Enduring Relations: Enhancing Economic Ties,” https://www.mofa.gov.bh/brasilia/en/home/.

[xxv] UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “The UAE Missions Abroad,” https://www.mofa.gov.ae/Missions/UAE-Missions-Abroad.

[xxvi] UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Embassy of the United Arab Emirates in Buenos Aires, https://www.mofa.gov.ae/en/Missions/Buenos-Aires.

[xxvii] UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs, United Arab Emirates Embassy in Brasilia, https://www.mofa.gov.ae/en/Missions/Brasilia.

[xxviii] UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Embassy of the United Arab Emirates in Mexico, https://www.mofa.gov.ae/en/missions/mexico-city.

[xxix] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, State of Kuwait, “State of Kuwait’s Diplomatic Missions Abroad,” https://www.mofa.gov.kw/en/kuwait-missions/kuwaiti-diplomatic-missions-abroad/.

[xxx] Foreign Ministry of Oman, “Embassies and Consulates abroad,” https://www.fm.gov.om/ministry/embassies/embassies-and-consulates-abroad/.

[xxxi] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, State of Qatar, Qatar Embassy in Buenos Aires, https://buenos-aires.embassy.qa/.

[xxxii] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, State of Qatar, Qatar Embassy in Brasilia, https://brasilia.embassy.qa/.

[xxxiii] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, State of Qatar, Qatar Embassy in Mexico City, https://mexico.embassy.qa/.

[xxxiv] “Brazil,” OEC, https://oec.world/es/profile/country/bra.

[xxxv] “Argentina,” OEC, https://oec.world/es/profile/country/arg.

[xxxvi] “Mexico,” OEC, https://oec.world/es/profile/country/mex.

[xxxvii] “United Arab Emirates,” OEC, https://oec.world/es/profile/country/are.

[xxxviii] “Saudi Arabia,” OEC, https://oec.world/es/profile/country/sau.

[xxxix] “Kuwait,” OEC, https://oec.world/es/profile/country/kwt.

[xl] “Oman,” OEC, https://oec.world/es/profile/country/omn.

[xli] “Bahrain,” OEC, https://oec.world/es/profile/country/bhr.

[xlii] “Qatar,” OEC, https://oec.world/es/profile/country/qat.

[xliii] Author’s compilation based on data from ALADI, available at https://www.aladi.org/accesoamercados/estadisticascomercioexterior/.

[xliv] Saudi Arabia Visa Requirements, VisitSaudi.com, https://www.visitsaudi.com/es/plan-your-trip/visa-regulations.

[xlv] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Bahrain, “Entry Visas to the Kingdom of Bahrain,”https://www.mofa.gov.bh/en/visitiors-visas.

[xlvi] Visit Dubai, “Visa information,” https://www.visitdubai.com/en/plan-your-trip/visa-information.

[xlvii] Kuwait Government Online, Kuwait e-Visa website, https://www.e.gov.kw/sites/KGOEnglish/Pages/eServices/MOI/KuwaiteVisa.aspx.

[xlviii] Royal Oman Police, Oman e Visa, https://evisa.rop.gov.om/en/home.

[xlix] Ministry of Interior, Qatar, “Entry Permits (Visit Visas),”https://portal.moi.gov.qa/qatarvisas/index.html.

[l] Citizens of this country who are resident in the United Kingdom, United States, European Union or Gulf Cooperation Council countries can apply for an e-visa. In practice, this is a much simpler visa.

[li] Visas can be applied for online or on arrival when visiting to conduct business or invest.

[lii] A 90-day visa on arrival is available to citizens of this country.

[liii] It is possible to apply for an e-visa. Source: Royal Oman Police, “Visa Eligibility Wizard – Unsponsored Visas,” https://evisa.rop.gov.om/visa-eligibility.

[liv] A 90-day visa on arrival is available to citizens of this country. Source: Ministry of Interior, State of Qatar, https://portal.moi.gov.qa/wps/portal/MOIInternet/departmentcommittees/ganationalborderexpatriateaffairs/!ut/p/a1/hc1BDsIgEAXQs3gCPlQbWI5ohFJFQxNbNoaVIdHqwnh-sXGrzmp-8uYPi6xncUzPfE6PfBvT5Z1jfdopEFcezmu1Liu5zpu9CCQKGAqwJOeGgztpIEGha7ql1wLg_-6PLE6kMSuLKsBt2roqDe1WC30A5OIDfr2YAL4Mgd2vPbKl2QsZTYcr/?1dmy&urile=wcm%3apath%3a%2Fwcmlib-internet-en%2Fsa-departmentcommittee%2Fgeneraladministrationofnationalitybordersandexpatriateaffairs%2F937038a1-7068-4e28-9743-afcf845c3706

[lv] Ibid.

[lvi] Ibid.

[lvii] Ibid.

[lviii] Ibid.

[lix] Ibid.

[lx] Ibid.

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] Ibid.

[lxiii] Ibid.

[lxiv] Visa on arrival free for 30 days.

[lxv] https://www.migraciones.gov.ar/accesible/indexdnm.php?visas.

[lxvi] https://www.gov.br/mre/pt-br/embaixada-lima/espanol/sector-consular/viaje-a-brasil/revisa-si-necesita-de-visa-para-viajar-a-brasil.

[lxvii] https://www.gob.mx/inm/documentos/paises-y-regiones-que-requieren-visa-para-viajar-a-mexico?trk=public_post_comment-text.

[lxviii] US visa holders can apply for an Electronic Visa Authorization (EVA) to enter Argentina. In practice, this is a much simpler visa.

[lxix] Ibid.

[lxx] Ibid.

[lxxi] UNCTAD, International Investment Agreements Navigator-Brazil, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/countries/27/brazil.

[lxxii] UNCTAD, International Investment Agreements Navigator-Mexico, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/countries/136/mexico.

[lxxiii] Nicholas Lyall, “GCC Economic Objectives in Latin America in the Shadow of the Rio G20 Summit: Complementary Investment Environment and the Role of Gulf Sovereign Wealth Funds,” TRENDS Research & Advisory, October 16, 2024, https://trendsresearch.org/insight/gcc-economic-objectives-in-latin-america-in-the-shadow-of-the-rio-g20-summit-complimentary-investment-environment-and-the-role-of-gulf-sovereign-wealth-funds/.

[lxxiv] Paulo Botta, “Middle Eastern Defense Industries and their links to South America,” TRENDS Research & Advisory, September 1, 2024, https://trendsresearch.org/insight/middle-eastern-defense-industries-and-their-links-to-south-america/.