The war in Ukraine has reached a devastating stalemate, resulting in a major humanitarian crisis, displacing millions of Ukrainian civilians. Data from February 2022 indicates that over 14 million Ukrainians, roughly 35% of the population, have fled their homes since the onset of the war. [1] Some have left Ukraine entirely, becoming refugees, while more than 4.8 million remain internally displaced within the country, although the actual number is considered to be much higher.[2] As of today, nearly 6 million Ukrainian refugees are registered in Europe alone, resulting in the largest forced migration Europe has witnessed since the end of World War II,[3] with an additional half million recorded beyond the continent.[4]

A significant number of these refugees have settled in Moldova, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. Poland, however, has received the highest number of incoming Ukrainians, accommodating nearly 60% of all refugees.[5] Poland’s geographical proximity to Ukraine, combined with the supportive response from local communities and the government, facilitated the provision of shelter, healthcare, and education for Ukrainian refugees. The Polish government’s efforts reflect a strong commitment to its solidarity with Ukraine.

Amidst the Ukraine war, displaced women and girls, who make up nearly 90% of those fleeing the crisis, have faced multifaceted challenges, including healthcare disparities, educational gaps, and economic insecurity, all profoundly impacting their lives and necessitating comprehensive interventions to safeguard their rights, well-being, and agency.

Displacement of women and girls

Out of concerns over the potential extent and unknown scope of the war, women with children have been compelled to flee their homes out of a sense of duty to ensure the safety of their children. Ukrainian women’s agency, according to a recent study, has often been constrained by this sense of responsibility.[6] As a result, women have made up a disproportionate share of those forced to flee their homes, with 60% of internally displaced Ukrainians being women.[7] This trend continues when looking at the broader population in need. The UN estimates that nearly 14.6 million people inside Ukraine will require humanitarian assistance in 2024, with women and girls again comprising more than half of those in need. [8]

Challenges faced by displaced women and girls

There is a significant correlation between displaced individuals and Gender-Based Violence (GBV). Displacement often exacerbates pre-existing vulnerabilities and inequalities, including those related to gender. Displaced women and young girls, as well as marginalized groups, which can include those living with disabilities, the elderly, and migrant workers, all remain at high risk of GBV in Ukraine.

Conflict and violence represent the primary drivers of displacement globally. However, it’s essential to recognize that the loss of economic security also plays a significant role in forcing individuals, particularly women, to flee their homes. This economic vulnerability can expose them to the heightened risks of GBV. Women looking to flee Ukraine in search of work abroad have also fallen victim to sex trafficking. Criminal syndicates, including some operating within Ukraine, entice women with promising job prospects overseas, only to coerce them into the sex trade upon arrival. The economic strain stemming from the conflict exacerbates vulnerabilities, particularly for single mothers who, despite losing their livelihoods due to the ongoing war, are compelled to support their families, rendering them susceptible to exploitation.[9]

The war in Ukraine has also led to increased conflict-related sexual violence, with nearly 90% of cases never being reported. In response, Ukraine ratified the Council of Europe’s Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence (also known as the Istanbul Convention) in November 2022, which established “minimum standards for the prevention, protection, and prosecution of violence against women and domestic violence” and remains a critical step certifying the observance of human rights by the Ukrainian government.[10]

The Ukrainian government is actively implementing the Istanbul Convention, a treaty dedicated to combating violence against women and domestic violence. This includes revising existing legislation to align with the convention’s requirements, such as streamlining protective orders and updating the criminal procedure code. Additionally, a strong focus is being placed on preventative measures through public awareness campaigns that challenge harmful gender stereotypes. Specialized centers offering medical, psychological, and legal assistance are being established to create a comprehensive support network for victims. Collaboration across various sectors, including law enforcement, courts, social services, and NGOs is being emphasized to ensure a coordinated and effective response. These combined efforts demonstrate the Ukrainian government’s commitment to tackling violence against women and domestic violence.

The impact of displacement and early education: long-term repercussions

War universally impacts innocent children in a multitude of ways, including unprovoked attacks leading to death and injuries, mass displacement, and disruptions in education. The war in Ukraine has remained no different, with at least 600 children killed and more than 1,350 injured since the onset of conflict.[11] The destruction of schools, hospitals, and residential buildings has left a devastating impact on the physical and mental well-being of Ukraine’s youngest populations.

According to Ukraine’s Ministry of Education and Science, as of October 2023, 365 educational institutions have been destroyed, and an additional 3,793 have been damaged as a result of the war.[12] In total, 7,000 schools remain inaccessible, either as a result of damages or due to the lack of bomb shelters amidst ongoing threats of air strikes.[13] Consequently, approximately 5.3 million Ukrainian children have experienced learning losses due to the limitations of traditional learning opportunities.[14]

The COVID-19 pandemic familiarized children worldwide with continuous online learning, enabling students in Ukraine—specifically, those who were not displaced—to more seamlessly transition back to online learning following the implementation of martial law. However, consistent disruptions in electricity and internet services, along with damage to personal devices like laptops and tablets due to bombings of educational facilities and residential buildings or during emergency evacuations, have significantly hindered online learning for those remaining in Ukraine.

Although internally displaced children are given priority admission to schools in Ukraine, most children often study remotely due to the flexibility of online learning, as most internally displaced children face unstable circumstances and frequent relocations. Additionally, online platforms can offer continuity in education, preserving access to learning resources and support systems despite disruptions. Nonetheless, such living conditions remain unconducive to a structured, long-learning process.

In April 2024, the first purpose-built underground school was inaugurated in Kharkiv, a northeastern city just 35 kilometers from the Russian border, in response to frequent missile attacks. Prior to the opening, most in-person classes were held in subway stations deep underground, which were capable of withstanding even nuclear explosions. The new underground school in Kharkiv provides parents and educators with peace of mind as a much-needed safe space for in-person learning during the ongoing war. While this undoubtedly improves children’s social well-being compared to online education, it’s important to acknowledge the limitations. With a capacity for only a small fraction of Kharkiv’s 57,000 schoolchildren, the ‘bunker school’ cannot serve as a realistic, long-term solution for the city’s educational needs.[15]

As of January 2024, nearly 2 million Ukrainian students continue to study online, while some combine distance learning with in-person classes, when possible. However, more vulnerable communities, including low-income families, children in orphanages, children with disabilities, and those with special educational needs, often lack the financial resources to obtain electronic devices, undermining the ability of educators to reach a spectrum of students.[16] To help fill the void, UNICEF, in collaboration with the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, recently delivered 39,000 laptops to middle and high school students who study remotely in Zaporizhzhia, the Kharkivska region, and the Khersonska region.[17]

For educators, the current priority is reintegrating schoolchildren into traditional classroom settings. This includes encouraging children from internally displaced families to enroll in schools located in close proximity to where they currently reside. This shift is crucial for both the psychosocial development of these children and their successful integration into their new communities. Research suggests that online learning can have long-term negative effects, including a decline in learning quality and a lack of development of essential in-person communication skills.

Safe and affordable housing for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs)

Due to the widespread destruction of homes and apartment buildings, displaced women and children often struggle to find safe and affordable shelter. As the war continues to rage on, with further damage expected to residential buildings and infrastructure, the trend of internally displaced persons (IDPs) is expected to continue.[18] One primary challenge is that IDPs often lack the financial resources to rent alternative accommodations; this is particularly the case for elderly women, as pension payments and IDP benefits are not always applicable for citizens who are forced to move from their hometowns to other areas within the country. For instance, a citizen may be denied an IDP certificate if they have lost their identification, such as their passport, or lack proper evidence proving residency in the territory from which they fled.[19]

As a result, and despite the dangers, older generations often opt to remain in occupied territories, citing that at least there, they have “a flat or a house, a garden and a supportive social network that they do not have in other parts of Ukraine.”[20] Likewise, IDPs living with disabilities or those who have escaped with their beloved family pets often face obstacles when finding suitable housing and transportation options. This limited mobility, especially for the disabled, continues to undermine relocation efforts and separates families, obliging minorities to remain in occupied areas. As of June 2022, 13% of families fleeing their territories in Ukraine had at least one disabled family member.[21]

Through Ukraine’s State Agency for Youth and Housing, the state has begun implementing a program that provides preferential mortgage lending at 3% for up to 30 years for IDPs, funded by a grant provided by the German Government. Vice Prime Minister Iryna Vereshchuk has urged that IDPs must be provided with more affordable housing solutions, adding the government should prioritize sourcing “additional financial resources and address our international partners.”[22]

Impact of conflict on women’s and girls’ health

Since February 2022, 1,567 attacks on medical facilities in Ukraine have severely hampered healthcare professionals’ capacity to deliver timely and proper care to those in need. [23] The influx of IDPs created a strain on physicians who remain inundated with patients, attempting to provide care under a system that is highly overstrained. Forced displacement has led to a decreased availability of doctors and medical staff, impacting the availability of patient care. Since the start of the war, Ukraine’s medical workforce decreased by 14%, equivalent to 89,000 personnel.[24] In addition, an increase in the price of medicines and supplies, in conjunction with growing levels of poverty, has also created barriers to the provision of healthcare services in Ukraine.

The ongoing occupation and relentless shelling of Ukrainian cities have crippled the healthcare system’s ability to function, affecting access to critical care and the delivery of medical supplies. For women living in rural areas, particularly those in the vicinity of the heaviest bombardments, access to maternal care has significantly deteriorated due to the disruption of logistical routes. At the onset of the war, nearly 265,000 women were due to give birth, with some forced to do so with limited medical access under dire conditions, including a lack of electricity, heat, or water.[25]

Psychological trauma and vulnerability to violence

Due to displaced personnel, staffing shortages have significantly reduced the availability of specialty healthcare services, including clinical psychology. This is particularly concerning as the demand for mental health services is increasing. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that nearly 9.6 million Ukrainians may need mental health services due to the war, with conditions ranging from anxiety to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[26] This situation is especially detrimental to women and girls who have experienced psychological trauma because of the conflict.

Following the ratification of the Istanbul Convention, Ukraine began implementing practical solutions to ensure existing legislation would align with the treaty’s provisions. The government began by taking an integrated approach between state bodies, social services, and human rights organizations to help combat gender-based, domestic, and sexual violence. A whole-of-government approach remains essential to effectively combating GBV.[27]

Ukraine’s government has also begun taking steps to prioritize preventative measures, including the launch of awareness campaigns highlighting the root causes of gender-based, domestic, and sexual violence and countering the narrative surrounding gender stereotypes. The government is also establishing networks of specialized medical, psychological, and legal assistance centers and improvements are being made to the quality of victim hotlines, offering a critical first step for survivors of abuse.

Economic insecurity

2022 remained a tumultuous year for Ukraine’s economy. In addition to upending peace and stability in Eastern Europe, the war resulted in a loss of income for millions, with the country’s GDP plummeting nearly 30%.[28] According to World Bank estimates, poverty rates in Ukraine rose from 5% pre-war to 24% by the end of 2022, forcing 7.1 million Ukrainians to live below the poverty line.[29] During the initial months of the conflict, millions fled to safer areas or left the country altogether, and public transportation largely ceased. As a result, nearly 75% of small businesses halted operations.[30]

Following the destruction of roads, schools, hospitals, and critical infrastructure, including power stations, Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction is expected to surpass $486 billion,[31] highlighting a challenging and uncertain financial recovery. Despite the immense setbacks, Ukraine’s economy outperformed expectations in 2023, with an annual real GDP growth rate estimated at 5.7%, significantly higher than the previously forecasted 0.3%.[32]

As the war enters its third year, the ongoing conscription of Ukrainian men has compelled women to assume the responsibility of ensuring their households’ financial stability, despite the fact that Ukrainian women have typically undertaken traditional gender roles within their family units; raising children and caring for the elderly or people with disabilities. Although 64.8% of Ukrainian women obtained post-secondary education in 2021,[33] they currently account for 72% of the unemployed population.[34] This underscores that during times of conflict, women and female-headed households often remain the most vulnerable to humanitarian crises.

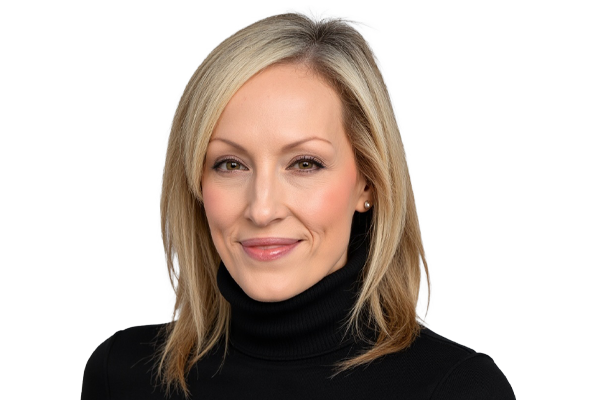

Liz Cookman, a Ukraine correspondent who has written extensively on the war’s socio-economic impacts, believes one of the primary challenges Ukrainian women face is that they often become the sole breadwinners and lone heads of traumatized households as men are fighting or perhaps even killed. Women in search of employment must tend to their children on their own while simultaneously dealing with the social stigma in what is still a deeply gendered society.

Initiatives for female economic empowerment

To aid in unraveling these outdated, pre-determined gender stereotypes in the face of adversity, the Ukrainian government began introducing several programs to integrate women into the labor market and encourage female-led entrepreneurship. Beginning in 2022, the government introduced financial incentive programs for companies employing IDPs. In 2023, these incentives were expanded to include compensation for companies that hire single women with children.[35] Ensuring that IDPs and single mothers secure employment helps reduce the government’s financial burden and allows aid agencies to allocate resources to other crises. Given that a significant portion of Ukraine’s female population holds higher education degrees, utilizing their skills and knowledge can also significantly contribute to the nation’s recovery efforts.

To help increase the employment rate and simultaneously attract female entrepreneurs, the government announced in March 2023 that it would begin offering micro-grants aimed at the development of small and medium-sized businesses, reflecting the government’s new overall strategic approach to promoting economic growth and social equality, as well as expanding women’s economic opportunities. As a result, women accounted for 60% of all new sole-proprietorships in Ukraine in 2023, while 31% of all executive leadership positions were held by female directors.[36]

Conclusion

The sunflower, the national flower of Ukraine, has long been synonymous with Ukrainian identity, not only due to its agricultural significance but also because Ukraine is one of the largest producers of sunflower oil globally. The symbolism of the sunflower, soniashnyk in Ukrainian, has come to represent much more than a local commodity to the Ukrainian people. Since the start of the war in February 2022, the sunflower has transformed into a global symbol of peace, resistance, and hope,[37] particularly for those who oppose the war and who wish for a return of stability in Eastern Europe.

In July 2023, the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology published a study titled “Self-Assessment of Happiness by the Population of Ukraine Before and After the Large-Scale Russian Invasion.”[38] Despite the domestic turmoil, Ukrainians’ sense of happiness remained largely stable. In 2021, just before the conflict, 71% of Ukrainians considered themselves happy, with only 15% feeling otherwise. By May 2023, even amidst the challenges of war, 70% still reported being happy, with a slight increase to 16% who did not. This resilience highlights the enduring optimism of the Ukrainian people.

This notion of resiliency is nothing new for Ukrainians. Despite the tragedies that have followed the war entering its third year, Ukrainians, for the most part, remain optimistic about their future. Another study conducted in December 2023 found that 73% of Ukrainians believe that in 10 years Ukraine will be a prosperous country within the EU (however, this figure is down from 88% in October 2022).[39]

This ambition for European Union membership stems from a hope of long-term security post-war, economic prosperity, and the protection of Ukrainian democracy. The Ukrainian government and its citizens continue to make significant strides in meeting EU standards and criteria, ensuring human rights commitments are met, and advancing gender equality. Ukrainians aspire to integrate with other European nations within shared pan-European political, economic, and security frameworks. This aspiration reflects their commitment to joining a collective system that promotes democratic governance, economic stability, and shared defense.

Bringing an end to the war in Ukraine may certainly rely on a number of external factors, mainly continued U.S. support, which could be in jeopardy depending on the outcome of the 2024 U.S. presidential election. Additionally, a stronger and more robust European defense industry is crucial to keeping pace with the conflict in Ukraine. If U.S. commitments are delayed or cease altogether due to a shift in policy priorities under new leadership in Washington, Europe must be prepared to step up and provide the necessary support.

In the meantime, it is crucial to implement comprehensive strategies at both the government level and through NGOs to protect the rights and well-being of all displaced individuals, particularly vulnerable populations, including women and children. A coordinated global effort is essential to mitigate the long-term impacts of this devastating conflict and to foster recovery and stability for Ukraine and its people, ensuring their future is one that reflects a sense of independence, dignity, and prosperity.

[1] International Organization for Migration [IOM], “Ukraine & Neighboring Countries 2022-2024: 2 Years of Response,” February 2024, https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/documents/2024-02/iom_ukraine_neighbouring_countries_2022-2024_2_years_of_response.pdf.

[2] National Institute for Strategic Studies, “Internal Forced Displacement: Scope, Problems, and Solutions,” October 24, 2023, https://niss.gov.ua/news/komentari-ekspertiv/vnutrishni-vymusheni-peremishchennya-obsyahy-problemy-ta-sposoby-yikh.

[3] People in Need, “Ukrainian refugee crisis: The current situation,” January 25, 2024, https://ukraine.peopleinneed.net/en/ukraine.

[4] UNHCR, “Ukraine Situation Flash Update #68 (16 April 2024),” ReliefWeb, April 16, 2024, https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine/ukraine-situation-flash-update-68-16-april-2024.

[5] UNHCR, “Ukraine emergency,” accessed May 7, 2024, https://www.unrefugees.org/emergencies/ukraine/#:~:text=There%20are%20nearly%205.1%20million,(as%20of%20May%202023).&text=More%20than%206.2%20million%20refugees,(as%20of%20July%202023).&text=Approximately%2017.6%20million%20people%20are%20in%20need%20of%20humanitarian%20assistance%20in%202023.

[6] O. Tarkhanova and D. Pyrogova, “Forced displacement in Ukraine: understanding the decision-making process,” European Societies (2023): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2023.2280680.

[7] National Institute for Strategic Studies, “Internal Forced Displacement: Scope, Problems, and Solutions,” op. cit.

[8] “Over 8 million women and girls in Ukraine will need humanitarian assistance in 2024,” UN Women, February 22, 2024, https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/press-release/2024/02/over-8-million-women-and-girls-in-ukraine-will-need-humanitarian-assistance-in-2024.

[9] L. Tondo, “Ukraine prosecutors uncover sex trafficking ring preying on women fleeing country,” The Guardian, July 7, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/jul/07/ukraine-prosecutors-uncover-sex-trafficking-ring-preying-on-women-fleeing-country.

[10] Council of Europe, “Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Istanbul Convention),” June 2017, https://www.coe.int/en/web/gender-matters/council-of-europe-convention-on-preventing-and-combating-violence-against-women-and-domestic-violence.

[11] “Ukraine: Significant increase in number of children killed,” UNICEF, April 26, 2024, https://www.unicef.ch/en/current/news/2024-04-26/ukraine-significant-increase-number-children-killed.

[12] M. Mygal, “Education in times of war: Challenges and prospects for Ukraine,” Institute of Analytics and Advocacy, October 23, 2023, https://iaa.org.ua/articles/education-in-times-of-war-challenges-and-prospects-for-ukraine/.

[13] “Ukraine: Two out of five children will miss school,” Save the Children, September 2023, Retrieved May 9, 2024, from https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/news/media-centre/press-releases/ukraine-two-out-of-five-children-will-miss-school.

[14] “Ukraine war continues to rob children’s hopes for future,” UNICEF, February 19, 2024, Retrieved May 8, 2024, from https://www.unicef.org/ukraine/en/stories/ukraine-war-continues-to-rob-childrens-hopes-for-future#:~:text=Approximately%205.3%20million%20children%20in,some%20rely%20on%20distance%20learning.

[15] I. Koshiw, “How Ukraine is trying to help its ‘lost generation,’” Financial Times, February 23, 2024, Retrieved May 9, 2024, from https://www.ft.com/content/d9acb360-9416-413b-a57b-9c6750e26e71.

[16] “Learning boost for Ukrainian children shut out of school for years,” Theirworld, January 24, 2024, https://theirworld.org/news/learning-boost-for-ukrainian-children-shut-out-of-school-for-years.

[17] “UNICEF delivers another 39,000 laptops for Ukrainian schoolchildren,” UNICEF, April 12, 2024, https://www.unicef.org/ukraine/en/press-releases/unicef-delivers-another-39000-laptops.

[18] “The Council of Europe continues supporting Ukraine in the development of new housing solutions for war-affected people,” Council of Europe Office in Ukraine November 30, 2023, https://www.coe.int/en/web/kyiv/-/the-council-of-europe-continues-supporting-ukraine-in-the-development-of-new-housing-solutions-for-war-affected-people.

[19] “IDP rights: What can internally displaced persons claim?,” Visit Ukraine Today, March 26, 2023, https://visitukraine.today/blog/1624/idp-rights-what-can-idps-claim

[20] O. Mikheieva and I. Kuznetsova, “Internally displaced and immobile people in Ukraine between 2014 and 2022: Older age and disabilities as factors of vulnerability,” Migration Research Series, No. 77, IOM, 2023, https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/pub2023-031-r-mrs77-internally-displaced.pdf

[21] “One year of war: Persons with disabilities in Ukraine,” European Disability Forum, February 24, 2023, https://www.edf-feph.org/one-year-of-war-persons-with-disabilities-in-ukraine/

[22] Ministry of Reintegration of the Temporarily Occupied Territories of Ukraine, “IDPs need more affordable housing programs,” March 4, 2024, https://minre.gov.ua/en/2024/03/04/idps-need-more-affordable-housing-programs/

[23] M. Buechner, “UNICEF won’t stop helping children in Ukraine: Full-scale war hits 2-year mark,” UNICEF USA, February 23, 2024, https://www.unicefusa.org/stories/unicef-wont-stop-helping-children-ukraine-full-scale-war-hits-2-year-mark

[24] “Ukraine: Impact of the conflict on the healthcare system and spotlight on specific needs,” ACAPS, September 22, 2023, https://www.acaps.org/fileadmin/Data_Product/Main_media/20230922_ACAPS_thematic_report_Ukraine_impact_of_the_conflict_on_healthcare_system_and_spotlight_on_specific_needs.pdf.

[25] European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, “Born under fire: despite the war, new life in Ukraine prevails,” European Commission, July 7, 2023, https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/news-stories/stories/born-under-fire-despite-war-new-life-ukraine-prevails_en.

[26] World Health Organization, “Reaching patients with severe mental health disorders: WHO hands over 12 vehicles for community health providers in Ukraine,” March 12, 2024, https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/12-03-2024-reaching-patients-with-severe-mental-health-disorders–who-hands-over-12-vehicles-for-community-health-providers-in-ukraine

[27] “Systems and legal frameworks to address gender-based violence,” In Joining Forces for Gender Equality: What is Holding us Back?, OECD Publishing, 2023, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/51b7a433-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/51b7a433-en

[28] European Parliament, “Two years of war: The state of the Ukrainian economy in 10 charts,” 2024, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2024/747858/IPOL_BRI(2024)747858_EN.pdf.

[29] “Two years of war in Ukraine: About 40% of the Ukrainian population will need humanitarian aid by 2024,” UNRIC, February 23, 2024, https://unric.org/en/two-years-of-war-in-ukraine-about-40-of-the-ukrainian-population-will-need-humanitarian-aid-by-2024/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20World%20Bank,hit%2C%20with%2080%25%20destruction.

[30] International Labour Organization, “How did the war impact the Ukrainian labour market?,” January 24, 2024, https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/how-did-war-impact-ukrainian-labour-market.

[31] U.S. Embassy in Ukraine, “A positive vision of Ukraine’s future,” April 10, 2024, https://ua.usembassy.gov/a-positive-vision-of-ukraines-future/.

[32] European Parliament, “Two years of war: The state of the Ukrainian economy in 10 charts,” op. cit.

[33] “European Neighbourhood Policy – East – education statistics,” Eurostat, 2024, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=European_Neighbourhood_Policy_-_East_-_education_statistics#Tertiary_education.

[34] “Over 8 million women and girls in Ukraine will need humanitarian assistance in 2024,” UN Women, op. cit.

[35] Ministry of Economy of Ukarine, “Government offers Ukrainian women programs for integration into the labor market and entrepreneurship, says Yuliia Svyrydenko,” Government Portal, March 24, 2023, https://www.kmu.gov.ua/en/news/uriad-proponuie-ukrainskym-zhinkam-prohramy-dlia-intehratsii-v-rynok-pratsi-ta-pidpryiemnytstvo-iuliia-svyrydenko.

[36] “56% of new FOPs in Ukraine in 2023 were opened by women,” Opendatabot, November 20, 2023, https://opendatabot.ua/analytics/businesswoman-in-war-2023

[37] J. Hassan, “The sunflower, Ukraine’s national flower, is becoming a global symbol of solidarity,” The Washington Post, March 2, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/03/02/ukraine-sunflower-solidarity-russia-war/

[38] Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, “Self-assessment of happiness by the population of Ukraine before and after the large-scale Russian invasion,” 2023, Retrieved from https://www.kiis.com.ua/?lang=eng&cat=reports&id=1257&t=7&page=1

[39] Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, “How do Ukrainians see the future of Ukraine in 10 years and readiness to endure material diffiulties,” Retrieved May 28, 2024, from https://kiis.com.ua/?lang=eng&cat=reports&id=1157&page=1.