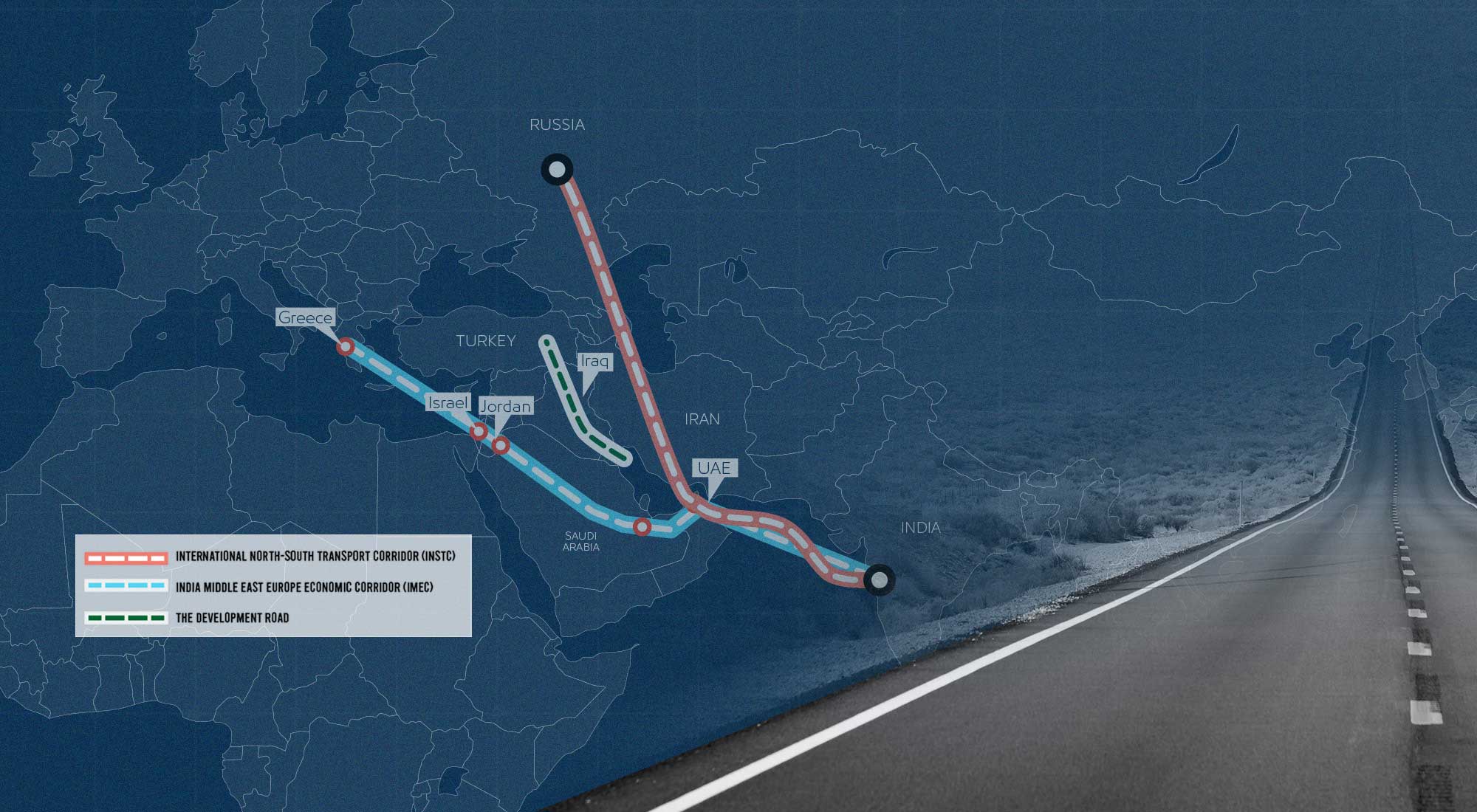

Amid the exacerbating rivalry between the U.S. and China, or Russia and the collective West, a more nuanced competition is unfolding over trade routes across Eurasia. Most of the new connectivity initiatives run through the Middle East, which, though always important in global affairs, now has attained a more central role amid the shifting global balance of power. From Saudi Arabia to Turkey to Iraq and Israel, all major regional actors along with greater powers in Eurasia are vying for quick and effective implementation of new trade routes. Echoing ancient and medieval silk roads, some of the modern initiatives are similar because of geography; others are completely new, but the pattern remains the same: the Middle East retains its position as a connective space between India/China and the European continent.

This paper examines the unfolding competition over trade routes and argues that Middle East countries are set to expand their maneuverability in the global arena by positioning themselves as nodal states in changing Eurasian connectivity.

From the Baltic Sea to the Gulf Region

The most significant and potentially largest trade corridor involves Russia’s and Iran’s efforts to develop the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a transportation route that, despite facing challenges, has the potential to reshape Eurasian connectivity. Born as an idea in the early 2000s, Russia, India, and Iran saw the 7,200 km-long project connecting the three countries as a new connectivity set to reshape Eurasian transportation and therefore the geopolitical landscape.[1]

Initially, the project made little significant progress. Russia primarily functioned as a transit hub for east-west connectivity, linking China and the European Union (EU), while its trade with Iran—conducted through the Caspian Sea or via Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, or Azerbaijan—fell short of expectations. Consequently, the corridor has developed several branches. The route known as the Trans-Caspian direction stretches across the Caspian Sea, serving as a crucial maritime link within the corridor. The western branch travels along the Caspian’s western coast through Russia and Azerbaijan, while the eastern route traverses Iran, enters Turkmenistan, and continues through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Alternatively, this route can bypass Uzbekistan, running directly through Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan along the Caspian Sea’s eastern coast.

Among these three branches, the critical link between Russia and Iran is through Azerbaijan, as it is the shortest land bridge between Russia and the Islamic Republic. Nonetheless, the Rasht-Astara railway section, located on the border between Azerbaijan and Iran, required millions of dollars in funding, still remains incomplete despite the pledges made by Moscow and Tehran. Moreover, the western branch is also more important since the most populous provinces of Russia and Iran are in the western regions of these countries, not the eastern parts, which are adjacent to Central Asia.

From a geopolitical perspective, the advantages of the INSTC are evident. It is set to reduce the delivery time of goods from India to Europe and potentially from Iran to Europe if and when the sanctions regime imposed on Iran ends.[2] The INSTC can connect Arabian Gulf and Indian ports with Russia, a vision that captivated Russian imaginations during its 19th-century southward imperial expansion. Access to warm water ports benefits both Russia and India, providing an alternative to lengthy sea routes for trade via the Red Sea. Ideally, the route would take 18 days from the Baltic Sea to reach India via Azerbaijan and Iran. Compared to the sea route through the Suez Canal, goods can be delivered via the INSTC twice as fast.

Geopolitical Incentives

The main factor driving the INSTC’s expansion is the war in Ukraine, which began after Russia launched its attack in 2022. Western sanctions on Russia have compelled the country to seek alternative routes to global markets, such as India, and most notably the Gulf states. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Iran in July 2022 accelerated talks on the need to complete the corridor, signaling a shift in Russia’s calculus and its recognition of the project’s importance.[3]

Although the Kremlin initially supported the INSTC, it never prioritized its rapid implementation. However, the project is now poised to help Russia and Iran increase trade and counter Western sanctions. Since 2022, both Moscow and Tehran have demonstrated a renewed commitment to completing the project, as evidenced by official statements and practical actions.

On 11 June 2022, two containers traveled from St. Petersburg to Astrakhan, then to the Iranian port of Anzali on the Caspian Sea, and ultimately to Bandar Abbas.[4] This test run coincided with Putin’s visit to Iran. Earlier, in April of the same year, Iranian Roads and Urban Development Minister Rostam Qasemi visited Moscow, where a comprehensive transportation cooperation agreement was signed.[5] In September, Iran, Russia, and Azerbaijan signed a declaration on the INSTC, emphasizing the project’s importance.[6] This followed the signing of a memorandum between the customs authorities of Azerbaijan, Iran, and Russia to facilitate transit traffic.

In mid-2023, Russia and Iran reached an agreement on the said railway section, and Moscow pledged to invest in the construction.[7] In January, Russian presidential aide and State Council Secretary Igor Levitin visited the rail route. During the visit, an agreement was reached to complete the rail project within three years, with Russia financing the 164-kilometer railway line and Iran financing the 12-kilometer section. Relatedly, in May, India and Iran reached a 10-year deal on the development and operation of the port Chabahar in Iran, which would allow India to connect Russia and Central Asia/Afghanistan via the INSTC.[8]

Challenges Remain

Despite the positive developments, serious challenges persist for the INSTC. Its infrastructure, undermined by U.S. sanctions, limits Iran’s transit potential to below 10 million tons, a stark contrast compared to the potential 200 million tons per year. There also remains a shortage of transit wagons and relatively poor road infrastructure, making it difficult to sustain higher traffic levels. The railway infrastructure remains poorly developed due to geographic constraints and a lack of investment, resulting in most of the country-wide transit being carried out by road, adding stress to its capacity.

Other logistical challenges include the lagging construction of tunnels and special bridges along the corridor in Iran as well as the lack of standardized railway gauge for the route. Russia is using a 152 cm gauge and Iran is using a 143.5 cm gauge, complicating potential railway operations.

Financial constraints also pose a challenge. Both Russia and Iran remain heavily sanctioned, and with the ongoing war in Ukraine and stalled nuclear negotiations, Western restrictions are likely to persist. Russia, typically capable of financing the Rasht-Astara railway section, now faces less promising prospects due to sanctions. This makes the absence of the 164-kilometer Rasht-Astara rail route all the more noteworthy.

Iran is also exploring alternative routes, including one through Armenia. In November 2022, Iranian Transport and Urban Development Minister Rostam Qasemi discussed transit routes from Armenia to Iran and the Gulf with Armenian officials.[9] In March 2023, Armenia proposed an Arabian Gulf-Black Sea corridor to connect India with Russia and Europe, coinciding with Armenia’s Foreign Minister Ararat Mirzoyan’s visit to India.[10] Yerevan has been bullish about the project, though, understandably, it faces significant financial problems.

More importantly, despite the unprecedented alignment of visions between Iran and Russia following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the two countries continue to harbor deep-seated distrust. Despite praising their cooperation driven by animosity toward the liberal order, uncertainties persist. Iranians are suspicious of Russia’s strategic goals in the South Caucasus and the Middle East. Even on issues like the provision of Iranian military drones to Russia, Iranian politicians are divided. Ordinary Iranians’ views of Russia, seen as an imperial power, have been negative, especially after the war in Ukraine.

There are also discrepancies in expectations regarding trade. For instance, in 2023, mutual trade decreased by 17 percent to $4 billion.[11] The problem is not so much in the decline of Iranian exports to Russia, but rather a steep decrease in Russian supplies to the Islamic Republic. More specifically, this decline attests to the overall dilemma that Russian businesses have experienced in selling their goods in Iran. The Islamic Republic has a different commercial culture, which stands in contrast to Turkey or the UAE, with which Russian entrepreneurs and traders have much in common.

Russian traders have trouble reaching importers in Iran without intermediaries and have a hard time avoiding bureaucratic hurdles. Generally speaking, Russian businesses have not yet adjusted to tastes in Iran but rather prefer Gulf countries and Turkey. In contrast, however, Russian investments in Iran have grown and in 2023, Russia became the biggest source of FDI for the Islamic Republic, with $2,76 billion out of the overall $4,2 billion.[12]

The Rise of the IMEC

Another significant trade corridor taking shape in the Middle East is the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). This initiative aims to create a seamless transportation and economic link between South Asia and Europe, passing through the Middle East. Proposed during the 2023 G20 summit in New Delhi, IMEC brings together major players like the United States, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and the EU.

In September 2023, the White House announced that the corridor would have two branches: one connecting India to the Arabian Gulf and another linking the Gulf to Europe.[13] The main feature of the corridor is a railway network that could provide a more efficient alternative to existing sea and road routes, facilitating smoother transit of goods and services among the involved nations.

The project promises benefits such as cost and time efficiencies, job creation, and increased transit route capacities. Additionally, the IMEC will feature critical cable and pipeline infrastructure and the transfer of green hydrogen between South Asia and Europe. Some aspects of the IMEC project are already underway. For example, a fiber-optic cable project unveiled in February 2023 by Israel aims to link India to Europe, running through Saudi Arabia and Israel.[14]

The broader context positions the IMEC as a competitor to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) under the Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment (PGII) umbrella. The IMEC initiative followed the G7 leaders’ pledge in 2022 to mobilize $600 billion to counter the BRI.[15] The timing of the IMEC announcement, just before the third BRI conference in China, further underscored its anti-BRI sentiment.

However, perspectives in the Middle East differ. For Saudi Arabia and the UAE, the IMEC is more about economic and infrastructural development than countering China. These Gulf countries have specific goals for developing their economies. Saudi Arabia’s aim aligns with its Vision 2030 economic diversification strategy, while the UAE sees this as an opportunity to boost its global standing and attract investments. Both countries view the new corridor as a chance to enhance their global stature amid the escalating U.S.-China rivalry.

Thus, for the Gulf countries, the IMEC fits into their broader strategy to position themselves in an emerging multipolar world. Their recent efforts to join the BRICS highlight their vision of a new world order where middle powers have greater maneuverability and are courted by great powers. They see this project as strengthening their evolving multi-vector foreign policies. This explains why the collective West’s efforts to push Saudi Arabia and the UAE to view the IMEC as a counter to the BRI have been ineffective. They seek diversification in their foreign policy ties.

India shares similar sentiments. While countering China’s initiatives in its neighborhood is a critical motivator, New Delhi’s approach is more driven by its increasing reliance on Gulf oil and substantial growth in bilateral trade. Additionally, embracing the IMEC does not exclude participation in other mega-projects. Both the Gulf countries and India are actively cooperating with Russia on the INSTC. The booming trade between these nations and Russia since the attack on Ukraine indicates that the Gulf countries are not going to abandon their nascent multi-vectorial foreign policy but will further diversify it.

Another motivation behind the project is India’s search for better routes to the EU market. Bilateral trade has surged, and discussions of free trade agreements are ongoing. The EU’s growing involvement in the Gulf region adds another layer of motivation for the new corridor. Moreover, the insecure conditions in the Red Sea, though they mushroomed only from early 2024, continue to serve as a powerful reminder for the diversification of trade routes.

However, the IMEC initiative faces significant challenges. Key considerations include gauging the actual demand for this corridor and navigating regulatory complexities. While existing infrastructure is crucial for new trade routes, challenges like underdeveloped railways in Greece and Jordan and building across Saudi Arabia’s vast deserts cannot be overlooked.

Moreover, the IMEC is a classic multimodal route comprising land and sea lines as well as a host of countries. Similar to other emerging initiatives like the Middle Corridor, which runs from Turkey/Black Sea to Central Asia, multimodal corridors usually face a lower chance of success. Coordinating several actors with different geopolitical outlooks often complicates the implementation of massive corridors. To become a successful project, the IMEC has to overcome these challenges.

There are also differing visions among major Eurasian actors. China, Russia, and Iran have different visions of connectivity in the Middle East, and the diplomatic dynamics among the U.S., Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Gulf countries remain unpredictable. It is yet unclear how or whether the IMEC initiative could improve Israel-Saudi Arabia ties. The war in Gaza questioned the prospects of IMEC implementation. On an official level, real progress on the IMEC would be possible only if Israel fulfilled the demands Saudi Arabia has announced, a big part of which is the two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Yet, Saudi Arabia and other Arab Gulf countries might also indirectly cooperate on the development of the IMEC with Israel. The war in Gaza is a significant obstacle, but it is in no way a definitive one.

Another issue is that, although the projected corridor highlights the longevity of ancient trade routes connecting South Asia and the Mediterranean, no major route has ever crossed the Arabian Peninsula from east to west. Instead, trade routes via Mesopotamia and the Red Sea were more attractive for millennia, whether during the Roman/Byzantine era or the global Mongol empire, which covered much of the Eurasian continent. It is no wonder that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan opposed the IMEC corridor and proposed his own version with Turkey playing a major role in the route from the Gulf via Iraq[16]—the vision that is more aligned with the traditional Silk Roads.

The Development Road

A third critical Silk Road initiative is the Development Road, which extends from Turkey to the Arabian Gulf through Iraqi territory. Conceived in the 1980s, the project has received a renewed push from Iraq and, notably, from Turkey, which is concerned about being excluded from the IMEC.

On 22 April, Turkish President Erdoğan made his first visit to Iraq in 13 years, where one of the major agreements was about the Development Road, a $17 billion mega-project connecting Turkey with the Arabian Gulf.[17] Along with Iraq and Turkey, the UAE and Qatar also signed the agreement, seeking alternative routes for trade with the Mediterranean basin and the EU.

For Ankara, the stakes are high as it seeks to mitigate its exclusion from the corridor project developed by Western powers, Gulf countries, and India. Known as IMEC, this route passes through Saudi Arabia and Israel. While the war in Gaza has limited the project’s chances, the crisis in the Red Sea could actually push its development. Following IMEC’s announcement, Turkey expressed its displeasure over its exclusion and proposed a 740-mile-long transit route via Iraq. This aligns with Ankara’s ambition to become a west-east and north-south trade and transit hub.

The stakes are likewise high for Iraq, which views the Development Road as a way to diversify its oil-dependent economy, where around 93% of revenue comes from the oil sector.[18] The route is seen as an opportunity to create a new economy focused on greener energy and new infrastructure, such as roads, railways, and settlements in desert areas.

The Development Road is a longstanding Iraqi ambition, first unveiled in the 1980s as the Dry Canal. Due to unfavorable geopolitical conditions, its realization was postponed multiple times. Now, with Turkey’s strong backing, uncertainties around IMEC, and instability in the Red Sea, the Development Road might play a significant, if not major, role as a viable trade route between Europe and Asia. In the current era of reconfiguring trade routes in Eurasia, where Russia, China, Iran, and the Arab states promote new connectivity projects, Iraq and Turkey also seek to play a greater role in connecting the Indian Ocean and the EU. The project reflects Iraq’s geopolitical ambitions to elevate its status as an important regional player.

Historical examples provide good reasoning behind the project. From the Roman to the Sasanian to the Arab periods, the trade route through the Arabian Gulf connecting the Indian Ocean with Asia Minor and Syria played a major role in the economic calculations of imperial powers. The Ottomans and Safavid Iran vied for control over this vital artery, while in the early 20th century, European powers sought connectivity between the Gulf and the Mediterranean.

However, several major issues hamper the modern Development Road. One is the unstable situation on the Iraq-Turkey border, where Ankara is concerned with the PKK, which has attacked infrastructure crossing the border.[19] Another challenge is Iran, which holds significant influence in Iraq and has its own ambitions to become a major trade and transit hub through the above-discussed INSTC. Iran also exerts influence on armed groups in Iraq, which could complicate the implementation of the Development Road.

The mega-project’s prospects are further questioned by the lack of a comprehensive feasibility study highlighting its weaknesses and potential. Geography also does not fully favor Iraq, as the success of the project depends on the situation in the Strait of Hormuz. If closed, it would kill transcontinental trade through the Development Road. Additionally, Iraq’s shore on the Arabian Gulf is considered too narrow to develop this massive corridor effectively.

Conclusion

The three initiatives discussed above are ambitious projects that, however, are facing numerous challenges ranging from geopolitical to purely financial. Not all connectivity projects are guaranteed to succeed, yet the near-simultaneous acceleration of three major projects in the Middle East indicates that the struggle over connectivity across Eurasia has entered a new phase. Russia, the U.S., Iran and the Arab Gulf countries have increased their efforts to reshape trade routes by pouring massive investments into roads and railways infrastructure. As was the case in ancient and medieval times, actors able to control trade routes in the Middle East are poised to play a major geopolitical role.

The dynamics behind the development of the IMEC, INSTC and the Development Road also indicate that modern states no longer prioritize the sea lines. The land routes remain as attractive as they have been in classical Silk Road times. The shift from sea to land could also reflect the growing instability in the Red Sea or in the Indo-Pacific region, where China-U.S. competition could easily evolve into an open confrontation.

[1] Nivedita Das Kundu, “International North-South Transport Corridor: Enhancing India’s Regional Connectivity,” Valdai Club, January 24, 2024, https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/international-north-south-transport-corridor/

[2] Evgeny Vinokurov, Arman Ahunbaev, “The International North–South Transport Corridor: Promoting Eurasia’s Intra- and Transcontinental Connectivity,” Research Gate, December 1, 2021, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357310308_The_International_North-South_Transport_Corridor_Promoting_Eurasia’s_Intra-_and_Transcontinental_Connectivity.

[3] Stefan Hedlund, “The problem-ridden development of a Russia-Iran axis,” GIS, August 24, 2023, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/russia-iran-axis/.

[4] “INSTC Shows The Way To Trade With Iran And Central Asia,” Maritime Gateway, July 1, 2022, https://www.maritimegateway.com/instc-shows-the-way-to-trade-with-iran-and-central-asia/.

[5] “Iran, Russia sign comprehensive transportation agreement,” Otaghi Iran Online, April 29, 2022, https://en.otaghiranonline.ir/news/33669.

[6] “Azerbaijan, Iran, Russia sign Baku Declaration on International North-South Transport Corridor,” Azertag, September 9, 2022, https://azertag.az/en/xeber/azerbaijan_iran_russia_sign_baku_declaration_on_international_north_south_transport_corridor-2284997.

[7] “Iran, Russia reach agreement on Rasht-Astara Railway,” Mehr News, January 18, 2023, https://en.mehrnews.com/news/196322/Iran-Russia-reach-agreement-on-Rasht-Astara-Railway.

[8] “India inks 10-year deal to operate Iran’s Chabahar port,” Reuters, May 13, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/india/india-sign-10-year-pact-with-iran-chabahar-port-management-et-reports-2024-05-13/#:~:text=NEW%20DELHI%2C%20May%2013%20(Reuters,a%20strategic%20Middle%20Eastern%20nation.

[9] “Armenia seeking new transit corridor through Iran,” Tehran Times, November 1, 2022, https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/478224/Armenia-seeking-new-transit-corridor-through-Iran.

[10] “Armenia proposes Iran-Black Sea corridor for Indian traders,” BM.ge, March 13, 2023, https://bm.ge/en/news/armenia-proposes-iran-black-sea-corridor-for-indian-traders/129070.

[11] “Tovarooborot Rossii i Irana v 2023 godu snizilsja na 17,3%, do $4 mlrd,” Interfax, February 28, 2024, https://www.interfax.ru/russia/948210

[12] “Rossija stala krupnejshim inostrannym investorom v Irane,” Forbes Russia, March 23, 2023, https://www.forbes.ru/finansy/486578-rossia-stala-krupnejsim-inostrannym-investorom-v-irane.

[13] “Memorandum of Understanding on the Principles of an India – Middle East – Europe Economic Corridor,” The White House, September 9, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/09/09/memorandum-of-understanding-on-the-principles-of-an-india-middle-east-europe-economic-corridor/.

[14] “Israel and Gulf states to be connected by fibre-optic cable,” Middle East Monitor, April 4, 2023, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20230404-israel-and-gulf-states-to-be-connected-by-fibre-optic-cable/.

[15] “G7 launches $600bn infrastructure plan to counter China,” Al Jazeera, June 27, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/27/g7-pledges-600bn-infrastructure-plan-to-counter-china.

[16] “Turkey’s Erdogan opposes India-Middle East transport project,” Middle East Eye, September 11, 2023, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkey-erdogan-opposes-india-middle-east-corridor.

[17] “Türkiye, Iraq sign 26 agreements,” Anadolu Agency, April 23, 2024, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/turkiye-iraq-sign-26-agreements/3199583.

[18] Harith Hasan, “Iraq’s Development Road: Geopolitics, Rentierism, and Border Connectivity,” Carnegie Endowment, March 11, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/05/iraqs-development-road-geopolitics-rentierism-and-border-connectivity?lang=en.

[19] İdris Okuducu, “Turkey’s Anti-PKK Operation and “Development Road” in Iraq Are Two Sides of the Same Coin,” Washington Institute, April 8, 2024, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/turkeys-anti-pkk-operation-and-development-road-iraq-are-two-sides-same-coin.