Introduction: The EU’s Quiet Global Power

When people think of global power, they often picture military might or economic dominance. Far less attention is paid to a subtler form of influence: the power to set rules that the rest of the world follows. This is the essence of the “Brussels Effect”—the European Union’s (EU) ability to project its regulatory standards far beyond its borders, shaping the conduct of businesses, governments, and even entire sectors across the globe.

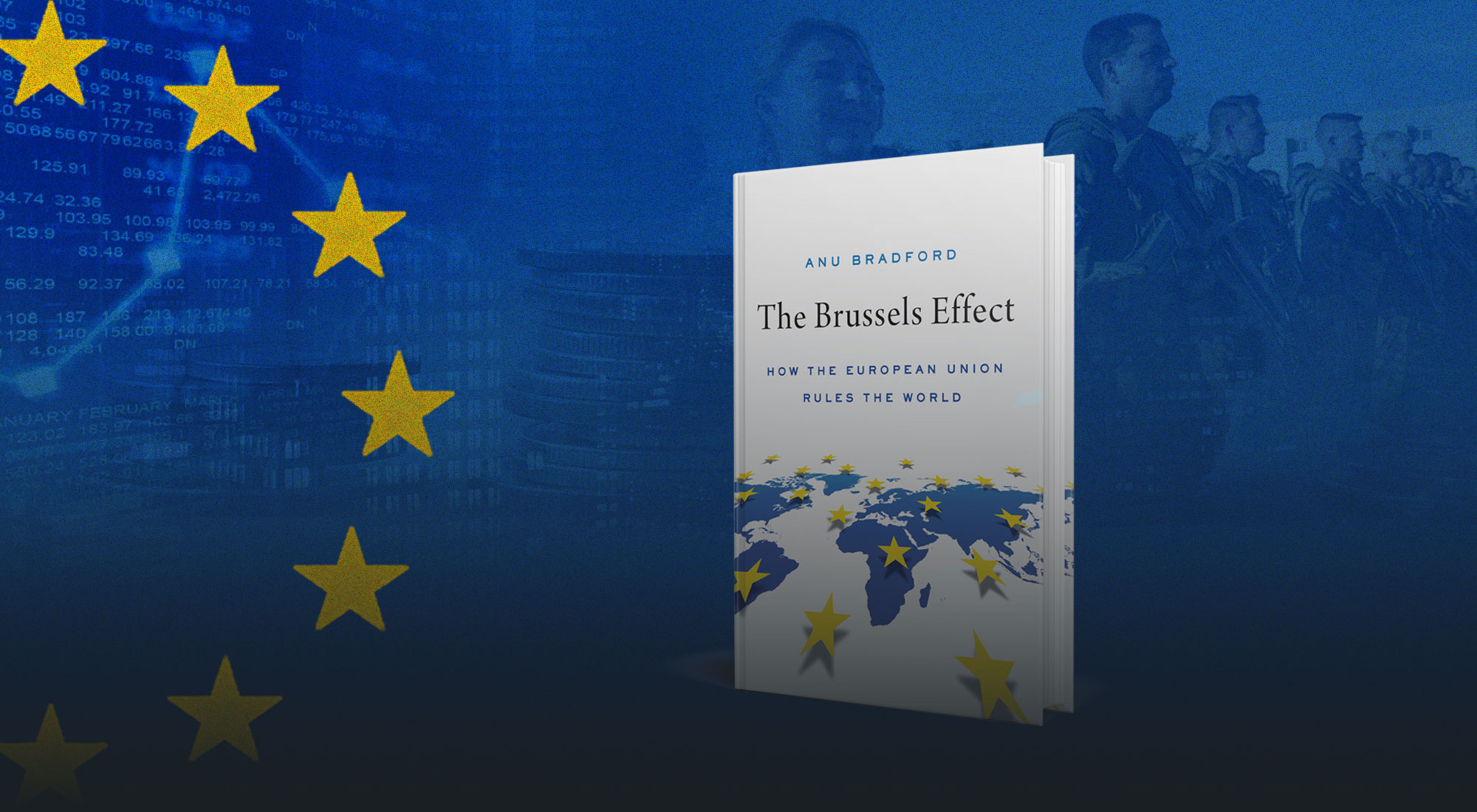

Coined by Professor Anu Bradford in her book The Brussels Effect (2020),[1] the term explains how EU rules—once made for the European market—often turn into global standards.[2] The idea is straightforward: companies that want to sell to the EU’s 450 million consumers must follow its strict rules. To save money and avoid running different systems in different places, they often apply the same rules to all their global operations. Over time, these EU rules shape not just company practices but also the laws of other countries.

Despite its importance, the Brussels Effect remains underestimated in global discussions. It shapes some of today’s most urgent and fast-changing policy areas, including artificial intelligence (AI), climate and environmental policy, and digital regulation. A prominent example is the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR),[3] which has inspired privacy laws from Brazil[4] to California.[5]

For foreign governments, understanding the Brussels Effect is crucial: it allows them to decide whether to align with EU rules, adapt parts of them, or develop competing standards. The EU’s influence stems not only from its large market but also from its sophisticated regulatory system, making its rules credible benchmarks—especially in areas prioritizing consumer or end-user protection.

On the other hand, this does not mean that the Brussels Effect is without its critics. Some argue that the power of big tech outstrips any potential influence of the EU’s AI Act,[6] while others point to digital fatigue, enforcement gaps, and the need to reinvent the EU’s regulatory approach.[7]

This article examines the evolution of the Brussels Effect, using the EU-UK relationship as a case study to show that Brexit, once seen as a clean break from EU law, proved far more complex. It also explores how countries worldwide respond to EU rulemaking and offers practical guidance for navigating and benefiting from Europe’s regulatory influence.

Expanding Frontiers: Brussels Effect 2.0

The Brussels Effect is neither entirely new nor unique to the EU. Scholars have long observed that jurisdictions with significant economic weight and strict regulations can influence practices beyond their borders. In the United States, for example, California’s stringent consumer rules prompted companies from other states to comply, a phenomenon known as the “California effect”.

In contrast, the “Delaware effect” illustrates the opposite dynamic, where competition between jurisdictions can lower standards—a “race to the bottom”. In U.S. states like Delaware, corporations are drawn by more business-friendly legal frameworks.[8] This dynamic challenges the Brussels Effect, as multinationals may seek alternative jurisdictions or exploit regulatory gaps, limiting the EU’s ability to unilaterally enforce its high standards.

Building on this, Anu Bradford highlights that the EU’s large, integrated market and evolving regulatory framework encourage foreign companies to adopt EU standards to sell goods or services within the bloc (de facto effect). Over time, these standards often influence domestic regulations in third countries, allowing the EU to shape global policies even without formal agreements (de jure effect), including in cases where countries might have resisted such rules through traditional negotiations.

Bradford identifies several conditions that make the Brussels Effect possible:

- Market size and significance: The jurisdiction must have a large, economically important market with consumers wealthy enough to make it indispensable to foreign suppliers.

- Regulatory capacity and commitment: It must be willing and able to set and enforce stringent rules.

- Regulation of immobile factors: These rules should apply to areas like consumer or worker protection, where those affected cannot simply relocate to avoid compliance.

Initially seen as an unintended by-product, the Brussels Effect is now viewed as a deliberate tool: EU regulations aim not only to manage the internal market but also to promote European values, protect economic interests, and maintain the EU’s role as a global standard setter.[9]

Regardless of the EU’s underlying motives, the Brussels Effect now shapes several globally significant areas:

AI: The EU Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act)[10] has been widely recognized as the first comprehensive regulatory framework for AI, combining a risk-based approach with outright prohibitions on certain practices. Global technology companies with AI portfolios are already aligning internal compliance strategies with the Act’s requirements.[11]

Environmental policy: The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)[12] acts as a green tariff on imports with high carbon emissions. By pricing carbon at the border, the EU ensures imported goods face costs like domestic products. CBAM incentivizes exporters to reduce emissions, often without formal agreements, promoting global decarbonization standards.[13]

Digital regulation: The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)[14] remains the most cited example of the Brussels Effect in practice, having inspired parallel privacy regimes in jurisdictions across the globe. Building on this legacy, the Digital Services Act (DSA)[15] and Digital Markets Act (DMA)[16] introduce comprehensive rules for platform governance, content moderation, and market fairness. Non-EU platforms operating in the European market face significant compliance adjustments, many of which spill over into their operations worldwide due to the impracticality of maintaining separate standards for different jurisdictions.

These sectoral examples illustrate an important dimension of the Brussels Effect: its impact on countries that trade extensively with the EU but remain outside its institutional framework. For such countries, access to the EU market often requires some degree of regulatory alignment—whether through formal harmonization, unilateral legislative changes, or de facto compliance by private actors.

This study focuses on the UK, the only country to have ever left the EU—a process known as Brexit[17]— making it a unique case for examining the challenges of stepping away from the EU legal system. While Brexit promised a clear break from EU rules, the following section demonstrates that escaping the EU’s influence has proven far more difficult than anticipated.

The Brussels Effect in Action: Lessons from Brexit

Brexit was framed as the UK’s decisive break from the EU, reclaiming sovereignty over its laws and regulations. Yet, the post-Brexit reality reveals that the UK remains heavily influenced by EU standards:

1. Trade in Goods: EU Standards as a Persistent Influence

Despite leaving the EU Single Market, the UK still aligns closely with EU product standards to preserve market access. Under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA),[18] goods that meet EU regulatory requirements benefit from tariff-free trade, covering safety, environmental, and labeling rules. Firms that fail to comply face non-tariff barriers, higher costs, and restricted access.[19]

As a result, UK food producers and manufacturers often maintain EU-compliant processes even when domestic rules differ. The cost of “dual compliance” has prompted many UK firms to adopt EU rules as their default, showing how economic incentives reinforce EU regulatory influence.[20]

2. Services and Financial Markets: Conditional Divergence

The UK expected more freedom to set its own financial services rules after Brexit. In practice, this freedom is limited. To access EU markets, UK firms must meet EU standards under the system of “equivalence”. The UK has made some changes in areas like crypto assets or certain fintech rules, but in core sectors like banking, investment, and insurance, the UK continues to align closely with EU regulations.[21]

This alignment ensures smooth cross-border transactions and helps maintain London’s position as a global financial hub, since diverging from EU rules could limit access to European clients.

3. Regulatory Choices: Alignment vs. Divergence

The UK’s post-Brexit regulatory strategy reflects a need to strike a balance between autonomy and market access. There were strong reasons to resist EU influence: sovereignty was central, with leaders and the public viewing Brexit as a chance to reclaim full control over laws, borders, and economic policy.[22] Regulatory divergence was also motivated by the desire to simplify or adapt rules to domestic priorities, reduce compliance costs for British businesses, and demonstrate the tangible benefits of Brexit to voters. Under former Prime Minister Theresa May, the Conservative government emphasized these “red lines, framing alignment with EU rules as a political compromise to be avoided.”[23]

Despite these motivations, practical considerations increasingly pushed the UK toward a more pragmatic approach. Trade realities made divergence costly: the EU remains the UK’s largest trading partner, and businesses on both sides face friction if rules diverge too sharply. Sectors such as food and agriculture, energy, and climate policy are particularly sensitive to differences in standards and regulatory frameworks.

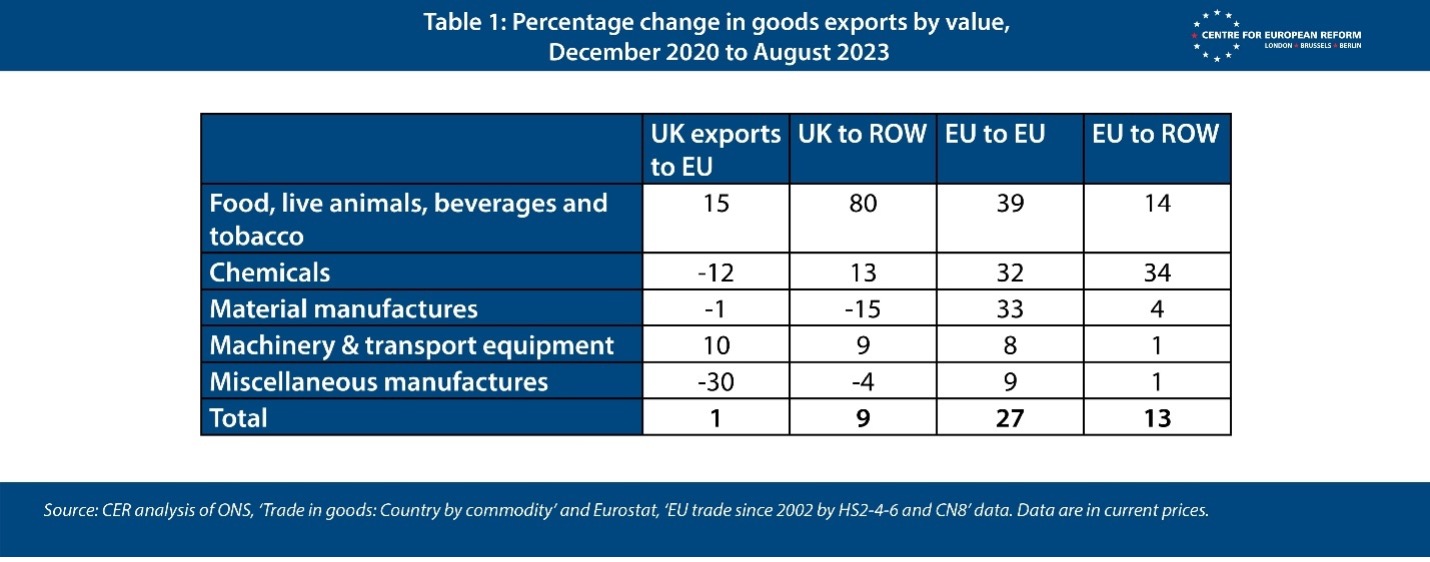

To put it into numbers, in the post-pandemic period (2020-2023), the UK missed out on a significant rise in European trade due to the border costs imposed by Brexit. If UK exports to the EU had grown at the same rate as those of EU member states, they would have been 27% higher in August 2023. Since exports to the EU account for roughly half of total UK goods exports, this implies an overall shortfall of about 13.5%, or £13.4 billion per quarter.[24]

4. The Status Quo: A Pragmatic Reset

Since the Labour government took office, the UK has awaited clarity on its post-Brexit relationship with the EU. The May 2025 “Lancaster House agreement” provides a cautious but significant step in this direction.[25] While it is not a formal agreement, but rather a “common understanding” that consists mainly of soft-law commitments without binding legal force, it outlines areas where future alignment with EU standards is possible.

These include negotiating an agreement on sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures[26] for trade, UK participation in the EU’s internal electricity market, and coordination of carbon pricing through linked emissions trading systems. By prioritizing alignment in these areas, the common understanding implicitly acknowledges the continuing influence of EU regulations—the Brussels Effect—on the UK. These measures could support closer cooperation in the future, but their impact depends on further negotiations and implementation.

In this way, the UK’s current approach demonstrates that leaving the EU has not diminished its regulatory influence. Instead, it has reshaped the relationship: the Brussels Effect continues to shape British policy choices, especially where divergence would be costly or disrupt trade. The recent “common understanding” reached at the Lancaster House summit set the stage for future cooperation, while acknowledging that full independence from EU standards remains neither politically nor economically feasible in key sectors.

What Should Foreign Governments Do?

Countries typically have three options when facing EU regulatory influence: align with EU rules, adapt selectively, or resist them. The EU’s regulatory reach—the Brussels Effect—creates both opportunities and constraints for foreign governments, depending on their economic priorities and political choices.

Alignment involves harmonizing national rules with EU standards to maintain market access. Japan provides a clear example: its data protection framework was recognized as adequate under the EU GDPR, reflecting deliberate alignment.[27] Ukraine also approximates its laws to EU norms to support trade and European integration. In both cases, alignment is motivated by economic and strategic incentives rather than purely normative goals.[28]

Adaptation entails modifying domestic policies selectively to accommodate EU requirements without full harmonization. Several Gulf states, including the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have adapted ESG (environmental, social, and governance) rules to meet EU export standards. By tailoring regulations for compatibility, these countries can access EU markets while preserving flexibility for local priorities.[29] This adaptive approach may also help lay the groundwork for the EU-UAE Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) talks, as regulatory alignment demonstrates willingness to cooperate, reduces trade frictions, and builds trust in the UAE’s commitment to EU-compatible standards.

Resistance involves maintaining distinct regulatory approaches or actively contesting EU norms. The United States has challenged mechanisms like the CBAM and the EU’s digital rules, citing sovereignty and trade protection concerns.[30] China has developed parallel governance systems, emphasizing domestic priorities and strategic autonomy over compliance with EU standards.[31] Arguably, both countries are able to resist EU regulatory pressure due to their large domestic markets, global economic influence, and strategic leverage in international trade, which limits the EU’s ability to unilaterally shape their policies.[32]

The UK example demonstrates how regulatory alignment gradually shifts from being ideology-driven to being primarily cost-driven. Post-Brexit, the UK initially resisted EU standards, reflecting Conservative commitments to sovereignty and market independence. Yet economic realities—including higher trade costs, business pressure, and the need to preserve EU market access—have prompted selective alignment in areas such as SPS measures, energy markets, and carbon pricing. This trend has been reinforced by the Labour Party’s victory in the UK Parliament, which brought a more pragmatic, less Eurosceptic stance. These two dynamics go hand in hand: we could argue that the electorate’s shift toward Labour enabled a more practical approach to relations with the EU.

Conclusion

The Brussels Effect could be defined as the EU’s unique ability to project its legal and regulatory standards internationally, turning its internal rules into “global benchmarks”. However, its influence should not be overstated; it is neither uniform nor absolute.[33] Its impact depends on various factors, including geographic proximity to the EU, the size of a country’s market, trade volume with the EU, and broader political considerations.

For some countries, alignment with EU rules is driven by geography, trade interdependence, and shared history—as in the case of the United Kingdom. Now outside the EU, the UK finds itself in a “pragmatic” stage of adaptation: despite Brexit, it must still align with many EU policies to secure smooth market access. For countries with weaker ties to the EU, the picture is more complex and requires deeper analysis. Even so, the Brussels Effect continues to shape incentives and regulatory debates, even where full harmonization is unlikely.

The United States and China illustrate another option: resistance. Both have rejected importing EU rules wholesale, a strategy only feasible for countries with large markets and significant global influence. Yet resistance does not necessarily mean insulation. The EU’s CBAM, for example, can already be regarded as a catalyst for change in China. Although CBAM currently affects less than 2% of Chinese exports, it is pushing Beijing to improve carbon data transparency and accelerate reforms of its national carbon market.[34] Globally, CBAM may act not only as a trade barrier but also as a reason to modernize environmental policies, especially in carbon-intensive industries.

This signals a shift in how the Brussels Effect operates. It was once seen as automatic and largely unilateral: EU rules, such as the GDPR, spread abroad simply because businesses seeking access to the European market had to comply. Foreign firms and governments adapted reactively, often with little input. Today, the dynamic is different. Non-EU countries are increasingly aware that EU regulation shapes their economies in fields such as AI, carbon taxation, digital platforms, data protection, ESG, and supply chain due diligence.

As a result, governments and businesses worldwide are no longer passive recipients. They are developing proactive strategies: monitoring EU law at an early stage, influencing international standards to reflect their own interests,[35] building regulatory partnerships through trade agreements, and preparing domestic industries for compliance in advance.

While external trade pressures, such as U.S. tariffs under President Trump, can influence the EU’s approach to trade agreements, they are unlikely to undermine its commitment to high regulatory standards.[36]

Overall, the Brussels Effect is no longer just about adaptation; it demands strategy. For policymakers worldwide, engaging with EU regulation is no longer optional—those who act early will shape the rules and safeguard their economic interests.

[1] Anu Bradford, The Brussels effect: How the European Union rules the world (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020). She first introduced the concept already in 2012 in her article: Anu Bradford, “The Brussels Effect,” Northwestern University Law Review 107, no. 1 (2012): 1–68.

[2] The Brussels Effect is most visible in internal market policies, where member states share decision-making with the EU under ‘delegated’ sovereignty. See also: Dennis Broeders, Fabio Cristiano, and Monica Kaminska, “In search of digital sovereignty and strategic autonomy: Normative Power Europe to the test of its geopolitical ambitions,” Journal of Common Market Studies 61, no. 5 (2023): 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13497.

[3] Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) [2016] OJ L119/1.

[4] Brazil’s General Data Protection Law of 14 August 2018 (LGPD).

[5] California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (CCPA) and California Privacy Rights Act of 2020 (CPRA).

[6] Emmie Hine, “Artificial intelligence laws in the US states are feeling the weight of corporate lobbying,” Nature 633(8030) S15 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-02988-0.

[7] James Görgen, “Brussels Effect Under Attack: Fatigue, Digital Fallacies, and Reinvention,” TechPolicy.press, September 10, 2024, Brussels Effect Under Attack: Fatigue, Digital Fallacies, and Reinvention | TechPolicy.Press.

[8] See Ofer Eldar and Lorenzo Magnolfi, Regulatory competition and the market for corporate law (Yale Law & Economics Research Paper No. 528; Yale International Center for Finance Working Paper, 2023) Yale University, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4374596. Or Guhan Subramanian, “The Disappearing Delaware Effect,” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 20, no. 1 (April 2004): pp. 32–59, https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewh023.

[9] Michel Bernat and Francesco Spera, The de jure “Brussels Effect”: Current legal trends in the EU’s unilateral regulatory globalization, European Papers, 5(3), 1347–1374, https://doi.org/10.15166/2499-8249/398. Or Sebastian Mack, “Show greenwashing the red card: How the EU can address flaws in its sustainable finance framework,” Jacques Delors Centre, October 30, 2023, available at: 20231030_Mack_SustainableFinance_UPDATED.pdf. This, however, also poses certain risks, particularly from increased internal corporate lobbying. See Maria Patrin, “The Brussels Effect: How the European Union Rules the World,” European Journal of Legal Studies 13, no. 1 (2021): 377–386.

[10] Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 July 2024 on artificial intelligence (AI Act).

[11] The AI Act, effective 1 August 2024, will be implemented in stages: bans on unacceptable-risk AI begin 2 February 2025, and governance rules for general-purpose AI (GPAI) take effect from 2 August 2026. An example of emerging transatlantic convergence is the joint statement of 23 July 2024 by the UK Competition and Markets Authority, the European Commission, and the US Departments of Justice and Federal Trade Commission on competition in generative AI and AI products: Joint statement on competition in generative AI foundation models and AI products – GOV.UK.

[12] Regulation (EU) 2023/956 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 2023 establishing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

[13] See the guidance of the European Commission: CBAM Guidance and Legislation – European Commission.

[14] Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR).

[15] Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 October 2022 on a Single Market for Digital Services and amending Directive 2000/31/EC.

[16] Regulation (EU) 2022/1925 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 September 2022 on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector and amending Directives (EU) 2019/1937 and (EU) 2020/1828.

[17] Brexit refers to the United Kingdom’s process of leaving the European Union, initiated by a referendum on 23 June 2016, followed by the triggering of Article 50 on 29 March 2017, and formally completed on 31 January 2020.

[18] For full text, see Trade and Cooperation Agreement, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/608ae0c0d3bf7f0136332887/TS_8.2021_UK_EU_EAEC_Trade_and_Cooperation_Agreement.pdf

[19] For an overview, see “Post-Brexit Trade: Navigating A New Course,“ Post-Brexit Trade | KPMG UK. For a more in-depth analysis, see The latest evidence on the impact of Brexit on UK trade – Office for Budget Responsibility. Also, European Parliament’s Assessment: EU-UK trade flows.

[20] See George Asiamah, “Political rhetoric vs practical reality of ‘Taking Back Control’: is the UK’s agri-food sector ready to break free from EU standards in the global arena?” Journal of European Public Policy 32, no. 6 (2024): 1492–1517, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2024.2340555.

[21] See, for example: Post-Brexit FinTech: UK and EU Paths Diverge, or Amanda Ward and Kevin Coleman, “EU-UK Divergence in Financial Services Regulation,” Grant Thornton, September 22, 2023, https://www.grantthornton.ie/insights/factsheets/eu-uk-divergence-in-financial-services-regulation/.

[22] This reflects the slogan ‘Take Back Control,’ widely used by the Vote Leave campaign during the 2016 UK Brexit referendum.

[23] Theresa May defined red lines in her speech from January 2017 as: leaving the EU single market and customs union and ending free movement of people. See the full speech here: The government’s negotiating objectives for exiting the EU: PM speech – GOV.UK.

[24] See the full analysis done by the Centre for European Reform: Brexit, four years on: Answers to two trade paradoxes | Centre for European Reform. For more recent data, see also: Weighed down by gravity: UK trade policy after Brexit | Centre for European Reform. Or A perfect storm: Britain’s trade malaise, weak growth and a new geopolitical moment. Recent data from the Office for National Statistics indicates a 3.6% increase in UK exports to the EU in Q2 2025, primarily driven by machinery and transport equipment. See UK trade – Office for National Statistics.

[25] The full text is available here: UK-EU Summit – Common Understanding (HTML) – GOV.UK. For a deeper examination of the post-Brexit reset, see Anton Spisak’s analysis: Back to Lancaster House – by Anton Spisak – A Newer World.

[26] In other words, sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures are rules and standards that countries set to protect human, animal, and plant health. They aim to prevent the spread of diseases, pests, or contaminants through trade.

[27] In January 2019, the European Commission formally adopted an adequacy decision that allowed unfettered personal data flows between the EU and Japan. See: EU and Japan conclude first review of their bilateral mutual adequacy arrangement | EU-Japan.

[28] Ukraine is aligning its laws with EU standards as part of its goal to join the EU. Official accession talks began in June 2024. See also: European Commission, “Ukraine’s path towards EU accession,” https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-solidarity-ukraine/ukraines-path-towards-eu-accession_en.

[29] In 2021, the UAE launched its Sustainable Finance Framework, followed by Saudi Arabia and Oman in 2024. See The case for a GCC Common Sustainable Finance Framework – PwC Middle East. Or Global rules, local impact: A region-by-region guide to sustainable finance regulation – Trade Finance Global Archive. The UAE’s Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) established a Green Fund regime, recognizing the EU Taxonomy Regulation as an “acceptable” green taxonomy, allowing funds to align with EU sustainability criteria. ESG in Abu Dhabi: How does it link itself to Luxembourg? | Global law firm | Norton Rose Fulbright.

[30] For CBAM, see Know your opponent: Which countries might fight the European carbon border adjustment mechanism? – ScienceDirect. Trump-era tariffs and CBAM represent different approaches: the former protects domestic industry, while CBAM targets carbon emissions and affects global supply chains: The Tariff Wars: Trump Tariffs vs. CBAM Carbon Tariffs. On digital rules: EU push to protect digital rules holds up trade statement with US, FT reports | Reuters.

[31] China’s approach to regulating digital platforms is state-driven, focusing more on political stability and state control than on the EU’s emphasis on rights and free-market considerations. China is advancing its own standards through initiatives like the “China Standards 2035” and the “Digital Silk Road”. See Towards a global approach to digital platform regulation | 03 Regulatory pathways and potential solutions.

[32] See, for example: “Trump says US may have to ‘unwind’ trade deals and will ‘suffer greatly’ if it loses tariff case,” Reuters, September 4, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/trump-says-us-may-have-unwind-trade-deals-will-suffer-greatly-if-it-loses-tariff-2025-09-03/.

[33] Also, for a discussion on why Europe cannot or does not need to regulate everything, see Theodore Christakis, ‘European Digital Sovereignty’: Successfully Navigating Between the ‘Brussels Effect’ and Europe’s Quest for Strategic Autonomy (December 7, 2020). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3748098 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3748098.

[34] Libing Wang, Ya Wen, Yun Zhang, “The impact of EU carbon border adjustment mechanism on China’s export and its countermeasures,” Global Energy Interconnection 8, no. 2 (2025): pp. 205-212, The impact of EU carbon border adjustment mechanism on China’s export and its countermeasures – ScienceDirect.

[35] See also: Pierre Haroche, “Geoeconomic Power Europe: When Global Power Competition Drives EU Integration.” Journal of Common Market Studies 62, no. 4 (2024): 938–954.

[36] But note also the recent case of a Commissioner allegedly blocking a major Google fine over concerns it could strain EU-US relations. MEPs blast Commission over claims it blocked Google adtech fine – Euractiv.