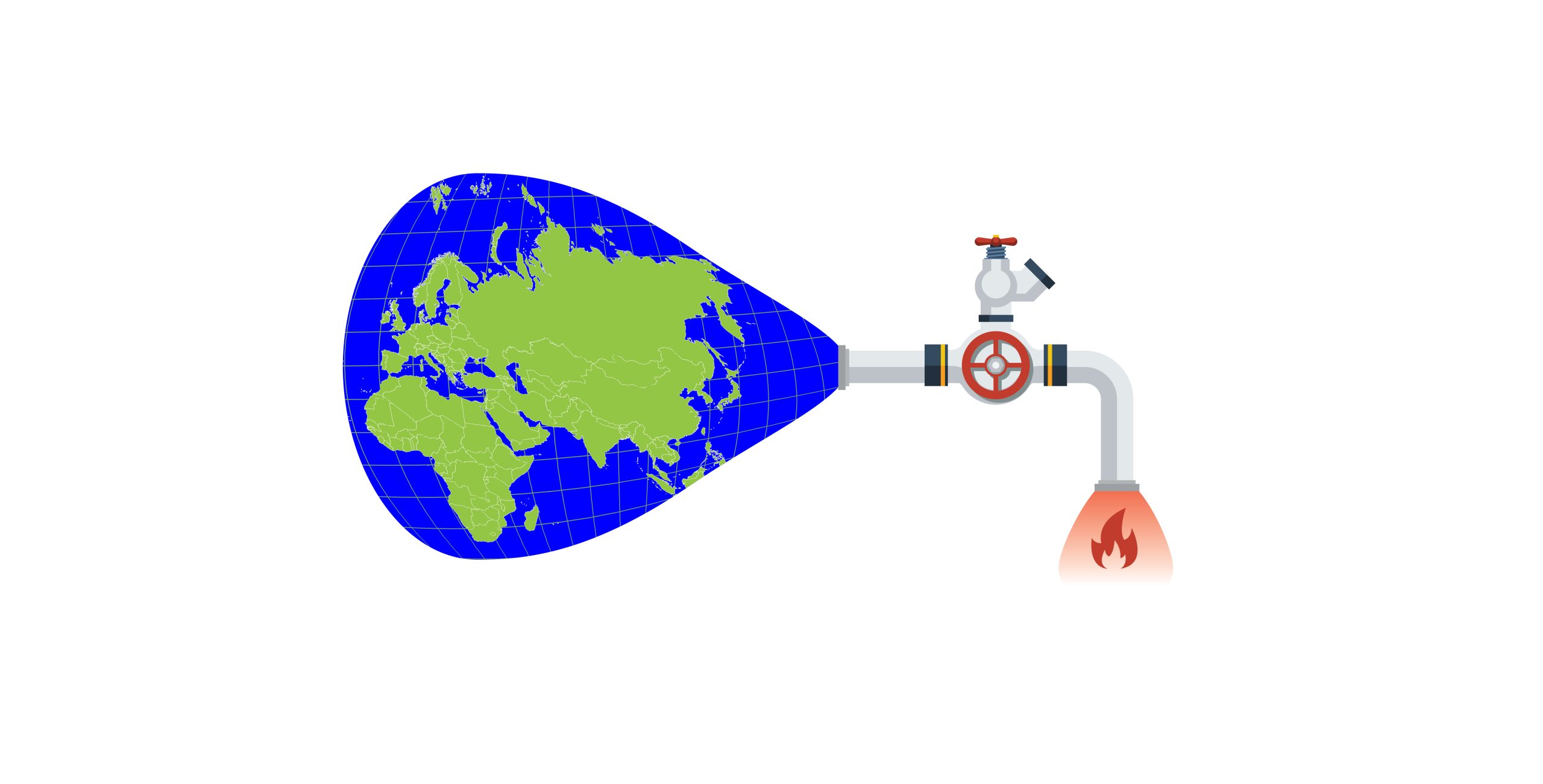

Global trends, shifting demand-supply distribution, technological advancements, changing energy mix and transforming infrastructure characterize the existing Eurasian energy security landscape. While the list goes on, each of these factors raises several questions regarding the anticipated future energy scenarios in the region, and beyond. In this article, I limit myself to one important subtopic, namely, what kind of future awaits the natural gas pipelines in Eurasia considering the growing liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry and trade globally. We are heading toward a more interconnected global gas market in which LNG is set to play a significant role, impacting Eurasian energy supply structures. So, the question is how the ongoing transformation will affect the use of pipelines as a primary means of transportation for natural gas.

Global energy market

To understand the global energy market, and analyze the Eurasian gas supplies, it is necessary to shed light on the continuously evolving role of natural gas in the energy landscape. In the year 2018, Oil (34 percent) of the global primary energy consumption followed by coal at (27 percent) and natural gas at (24 percent) According to BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019, natural gas is expected to leave coal behind in 2030 and is set to become the second-largest fuel in the global energy mix.

World total primary energy consumption by fuel in 2018**

*Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019

While in 1973, natural gas accounted for only 16 percent of the total primary energy supply on a worldwide scale, the rate increased to 21 percent by 2015. The evolution of the share of natural gas in electricity generation over the same period points to even greater expansion. This rate was 12.1 percent in 1973 and reached 22.9 percent by 2015. While in 1973, 1,224 bcm [billion cubic meters] of natural gas was produced worldwide, by 2016, it reached 3,613 bcm. In other words, the annual natural gas production has tripled over the last four decades.

The exploration, production, and trade of natural gas as well as its role in electricity generation, has developed significantly in recent decades. Moreover, the importance of natural gas is likely to continue to increase in the future. The dynamic expansion of Asian markets can be identified as an important factor behind the increase in demand for natural gas. The emergence of new actors on the supply side has also given fresh impetus to the global gas market.

For instance, the US, as a result of the shale gas boom over the past decade, has not only become a net exporter of gas but is now already among the top three LNG exporting countries. Since natural gas is widely considered as the cleanest form of hydrocarbon, the policy environment that encourages the use of environment-friendly energy resources will continue to urge a preference for natural gas over coal or other fossil fuels. This is set to create more demand for natural gas and hence fuel growth.

Pipelines vs LNG

The natural gas market is becoming more flexible, globalized and diversified. LNG is particularly important to this process of transformation as it enables the transportation of natural gas on maritime routes, which gives the gas market a higher degree of flexibility. LNG trade can take place under contracts of varying duration but it can also be conducted by spot market transactions.

To assess whether LNG can become more important than piped gas we have to first compare data related to their usage, which suggests the primacy of the pipelines. In 2018, 805.4 bcm of natural gas was exported/imported by pipelines globally while LNG deliveries amounted to 431.0 bcm. Based on the dataset below, between 2009 and 2018, the volume of piped gas trade increased by approximately 27.1 percent, while LNG grew by 77.5 percent.

Comparison of the volume of natural gas movements via pipelines and in the form of LNG (in bcm)[1]

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018[2] | |

| Pipeline | 633.77 | 677.59 | 694.61 | 705.5 | 710.6 | 663.9 | 704.1 | 737.5 | 740.7 | 805.4 |

| LNG | 242.77 | 297.63 | 330.83 | 327.9 | 325.3 | 333.3 | 338.3 | 346.6 | 393.4 | 431.0 |

[1] Data compiled from BP Statistical Review for World Energy 2010-2018.

[2] BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019

Comparison of the volume of natural gas movements via pipelines and in the form of LNG (in bcm)

While comparing piped natural gas to LNG, one should not lose sight of the cost of the technology applied. Vast spending on infrastructure, including liquefaction capacities, shipping, and regasification, is a precondition to enter LNG trade, while pipelines are relatively simple structures from a technological point of view. Accordingly, their installation is comparatively less expensive compared to the installation of LNG infrastructure. Geographical distance can, however, influence the commercial viability of pipelines. Pipelines in many cases have to traverse state borders or territories due to a lack of security and are subject to geographical conditions more than LNG, which can easily be transported through maritime routes.

The use of LNG does not oblige states – in some cases even transit states – to reach an agreement on the details related to the laying or the management of a common pipeline, which would require collective efforts from the stakeholders. It should also be taken into consideration that pipelines can easily become targets of sabotage or terrorist attacks. Countries in the Middle East are especially prone to such acts. Turkey, for instance, has been facing this kind of security challenges quite frequently, which can have wider ramifications for the country’s energy supply security and also for its objective to become a regional energy hub.

Pipelines in Eurasia

Despite the growing role of LNG globally, pipelines are becoming indispensable for natural gas supplies in Eurasia. First of all, the top four countries with the largest natural gas reserves – namely Russia, Iran, Qatar, and Turkmenistan – are located in Eurasia. The export data for 2017 suggests that the world’s top three gas exporters are also located in Eurasia: Russia, by far the largest exporter with 230.9 bcm, followed by Qatar and Norway with 121.8 bcm, and 115 bcm gas export volumes, respectively.

Looking at the top three suppliers, we must emphasize that approximately 93 percent of Russia’s natural gas export – 95 percent of the gas exports in the case of Norway – is transacted via pipelines. This suggests an almost fully pipeline-based gas trade. At the same time, as the largest LNG provider across the world, Qatar exports only 15 percent of its gas as piped gas. A majority of Qatari gas is exported in the form of LNG.

As the world’s largest natural gas exporter, Russia is a critical player in Eurasian gas dynamics and its pipelines are major geo-economic assets. Europe’s natural gas supply largely depends on the import of Russian gas. Approximately 40 percent of the gas import for member states of the European Union (EU-28) comes from Russia. Accordingly, natural gas relations, and pipeline diplomacy, have become an inseparable dimension of the EU-Russia relations. In the wake of the multiple Russia-Ukraine gas crisis, and their negative impact on the European supply security, the EU’s interest lies in shifting away from Russian gas and diversifying Europe’s gas import structure.

However, this does not mean that the EU member states would have a monolithic approach toward Russian gas. The NordStream2 pipeline project, which is under construction at the moment, is also being discussed most intensely. This pipeline will link Russia to Germany under the Baltic Sea and will add another 55 bcm per annum supply of Russian natural gas to the European markets. The project is being critically viewed from the EU side, given that it would further increase European dependence on Russian gas and pipelines. Interestingly, this is not the only very topical Gazprom pipeline project. The TurkStream pipeline that was officially inaugurated in January 2020, will enable 31.5 bcm gas flow from Russia directly to Turkey every year. At least a part of this gas will be available for export to Europe once the further transportation routes and other conditions are fulfilled.

China appears as an increasingly important new destination on Russia’s gas export map. The Power of Siberia pipeline that was just inaugurated in December 2019, will enable the export of 38 bcm Russian gas to China, once it will be operating at full capacity LNG production is on the rise in Russia, and its export volume is expected to grow to 32 bcm per annum by 2040. Based on the above figures it is evident that Russia is planning to add at least 124.5 bcm new export pipeline capacity to its existing pipelines. As a result, the primacy of pipelines will remain unchanged for Russia in the upcoming decade.

Access to natural gas resources largely depends on geography. A certain country with access to the sea can directly import or export LNG. Landlocked countries, on the other hand, are much more dependent on pipelines. Turkmenistan, for instance, has access to the Caspian Sea but has no access to the world ocean. As an analogy to the 19th-century rivalry for the control over Central Asia, today, the region is often labeled as the geopolitical space where the “Great Energy Game” takes place, and Turkmenistan undoubtedly plays a role in this.

Even though Turkmenistan sits over the fourth-largest natural gas reserve in the world, and the gas export is the main source of income for the country, the export of natural gas from Turkmenistan is possible only via pipelines. For decades, the country has been exporting to and via Russia, through the Gazprom-controlled Central Asia–Center pipeline infrastructure. Unfortunately, by January 2016, relations between the two countries went downhill and completely ceased gas supply. However, in 2019, Turkmenistan’s gas exports to Russia resumed to a limited extent. Based on a new contract inked on 1 July 2019, between Turkmengas and Gazprom, an annual volume of 5.5 bcm of Turkmen gas will be exported to Russia until 2024.

Turkmenistan is currently the largest piped gas exporter to China whose substantial natural gas demand growth can be partly satisfied with domestic production and from LNG import. However, significant further volumes can be exported to China through pipelines. Russia just commissioned the Power of Siberia pipeline and the construction of the so-called Line D from Turkmenistan to China is also on the agenda. Despite the delays due to some shortcomings in the project, in theory, it could add another 30 bcm extra pipeline capacity to the existing Central Asia–China pipelines.

In the case of Turkmenistan, two major pipeline projects are of key geo-economic significance. The so-called Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline has long been on the agenda but has made very limited progress. Once completed, this pipeline would be another export route for Turkmenistan’s gas to energy-hungry markets. The capacity of this pipeline is estimated to be 33 bcm per year. The other project is the Trans-Caspian pipeline, which has been intensively debated in the past two decades but continues to remain in the planning phase, without very bright prospects.

The idea behind this project is to open another window of export for Turkmenistan gas by constructing a 300km-long pipeline from the Western part of Turkmenistan under the Caspian Sea to Azerbaijan, where the gas could be transported to the Southern Gas Corridor. The EU views this corridor as a flagship initiative in its gas supply diversification plans. However, several complex legal, geopolitical, and commercial factors continue to limit the chances of this project.

Besides Russia and Turkmenistan, Iran with its second-largest gas reserves in the world and with a huge potential in the natural gas market also requires attention. This is important while assessing potential natural gas pipeline projects in Eurasia. Despite its enormous gas reserves and being the third-largest natural gas producer worldwide, Iran has not become a major exporting country so far due to its complex political and economic circumstances. However, as outlined in the country’s Sixth Five-Year Economic Development Plan (2016-21), by 2021, Iran aims to export 68-80 bcm of natural gas per year, and pipelines are expected to be the main infrastructure to transport these gas volumes. Today, Turkey and Iraq are the main export destinations for Iranian gas. Iran and Pakistan have concluded an agreement but the gas pipeline between the two countries has been only partially completed and the project faces many difficulties.

The projected capacity of this pipeline is 22 bcm. Once commissioned, it would undoubtedly mean an important export channel for Iran, and also an important source of gas for the energy-hungry Pakistan. Both India and Pakistan are facing dynamic gas demand growth. Hence, in theory, TAPI could become a major source of natural gas for the two South Asian countries. In addition to these projects, the construction of an Iran-India undersea gas pipeline, that would also involve Oman as an intermediary partner has also been actively discussed among the parties, but without much visible success so far. Given the slow progress with these projects, it seems that for India and Pakistan it is an obvious necessity to keep LNG in the focus. India is already the fourth-largest LNG importer in the world while Pakistan became an LNG importing country in 2015, and its import continues to increase since then.

Conclusion

Although this article does not seek to present a fully detailed evaluation of all the existing and planned natural gas pipeline projects in Eurasia, it argues that even if the trade of LNG is on the rise, pipelines will remain geopolitically and geo-economically important assets in the Eurasian energy security landscape. Energy-related interactions among states are getting more and more frequent in our age and pipelines are expected to play a major role. Besides, a regional character is observable in the pipelines vs LNG question within Eurasia: a substantial part of the border-crossing piped gas trade movements take place in the Russia-Europe relations, while LNG is most dominant in the Qatar-East Asia, and Qatar-South Asia relations.

Based on these submissions, and the fact that in Eurasia a large number of gas pipeline projects totaling hundreds of bcm in aggregate capacity are either in the planning or construction phase, it is pertinent to assert that pipelines will remain very crucial at least in the immediate future. At the same time, we can also recognize that the failure or at least delays to these projects are considerably frequent. Yet, when it comes to the future of pipelines in Eurasia, we can conclude that further new pipeline projects are on the agenda in several countries, and Russia stands out on that list. Moreover, pipelines from Russia to three very significant gas markets – Germany, Turkey, and China – are either under construction at the moment, or have just been commissioned recently.