BRICS expands with six new members

The 15th BRICS summit in August 2023 concluded with a declaration that invited six countries (the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Argentina, Ethiopia, and Iran) to become members from 1 January 2024. From a historic perspective, the term “BRICS” is an acronym representing initial letters of five major emerging countries that have the potential to dominate the world economy by 2050s. Established in 2009, it is an intergovernmental organization that acquired heightened importance in recent years as an alternative platform for emerging countries of the Global South against developed nations of the G7. Drawing attention to pressing issues around trade imbalances, income inequality, equitable access to finance, and alternative currencies to the US dollar, BRICS is an attractive advocacy platform for reforming global governance and pooling resources among developing nations in issue-based negotiations. The expectation from BRICS expansion is to have a more ambitious agenda and more forceful position, including a stronger push for reform of the global political, economic, and financial architecture to reflect the Global South’s rising profile.

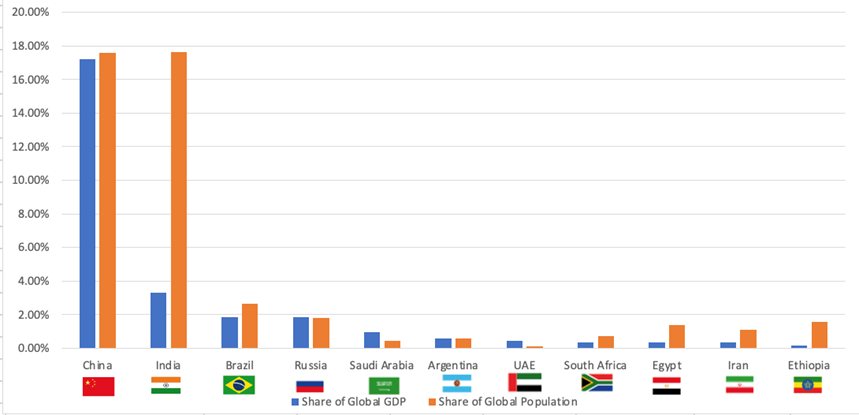

Figure 1: BRICS+ Share of Global GDP and Population, 2023

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), CSIS, European Journal of IR

Adding new members to BRICS represents a victory for China, which pushed for rapid expansion to remake the group into a counterweight to the G7.[1] By 2023, the BRICS nations had already overtaken the G7 states in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, as the initial five members of the group alone accounted for nearly 31.5% of global GDP, compared to 30.7% for the G7.[2] With the six new members, its share of global GDP on a PPP basis increases to 37%. The expanded organization of “BRICS+” not only represents a US$2.5-trillion economic powerhouse, but also brings together oil producers, energy consumers, large mineral resource holders, and funders of mega projects. The expansion increases BRICS+’s share of oil production from 20% to 42% and its reserves of global rare earths, which are critical for high-tech, defense, and energy sectors, to 72%, including three of the five countries with the largest reserves. All this shows that the addition of new members, if coupled with better cooperation within the group, can enable BRICS to wield greater influence over the global economy. At a time when the U.S.-led liberal international order fractures and the perceived inefficacy of the UN bodies disillusioned the Global South, BRICS connects several major emerging economies around common development interests and a quest for a multipolar world order.[3]

Figure 2: BRICS Countries – GDP, Population and GDP per Capita, 2023

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU)

Opportunities: Trade and Finance

The BRICS decision to invite six countries out of the twenty-two that applied (and forty that expressed interest) to join the bloc provides hints at geo-economic calculations behind the scenes. By inviting the UAE and Saudi Arabia, which act more assertively on the global stage and more independently of their traditional ally,[4] the U.S., India strengthens ties with two of its strategic partners while China pushes against Western influence in the Gulf. With the inclusion of the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Iran, BRICS+ now represents 80% of global oil production. Securing Egypt’s and Ethiopia’s membership also diminishes Western influence in a region increasingly balancing the U.S. with Beijing and Moscow for economic relief and arms deals.[5] As a case of “minilateralism”, BRICS forms a small coalition of like-minded states to advance multipolarity in an increasingly tumultuous and uncertain world.

For the Gulf countries, besides re-balancing their global positioning and diversifying their dialogue partners, stronger ties with India and China present scaling opportunities as a trade hub. A significant advantage stemming from BRICS membership is the reinforcement of non-oil trade with other members of the group, especially in the healthcare, education, and tourism sectors. As the UAE and Saudi Arabia gain enhanced access to African markets via Ethiopia, Egypt, and South Africa and consolidate their position as the Middle East hub of the China-backed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), their push for liberalization and harmonization of investment policies and cross-border transactions in Africa can also help support sustainable development for climate adaptation and mitigation.

The purpose of the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB), headquartered in Shanghai, China, is to provide financing for such cross-border trade, investment, and infrastructure projects. It is a multilateral bank with a more inclusive decision-making mechanism than traditional lenders and offers a non-Western alternative to fund emerging sectors such as fintech, clean energy, and digital transformation. With an “AA” credit rating from Fitch,[6] NDB has officially announced a 3-year plan to support local currency transactions following the induction of the six new members to its ranks. NDB is under pressure to raise and lend more in local currencies, and specifically, their plan is set to aid in lending to member countries, diminishing the number of transactions denominated in the US dollar. With a loan portfolio of US$32.8 billion, NDB lends in yuan and rand and considers raising funds through rupee-denominated bonds soon.[7] NDB’s Chief Financial Officer, Leslie Maasdorp, said that “the bank aims to increase local currency lending from 22% to 30% by 2026”.[8]

Many nations agree to end their dependence on the US dollar due to the heightened risks of financial sanctions as demonstrated in the aftermath of the Ukraine-Russia war. Instead of a broader push toward de-dollarization, however, BRICS+ is expected to accelerate trade in local currencies. The UAE can leverage its vast capital resources, managerial know-how, and international financial hubs of Dubai and Abu Dhabi to inject more cash into NDB, raise Dirham-denominated bonds, and perhaps host NDB’s operations or open a new Middle East regional office. India, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia intend to settle cross-border transactions with their respective native currencies, and BRICS+ NDB can help increase interoperability, economic integration, and mechanisms for digital payments between central banks.

Challenges: Cohesion and Policy Coordination

BRICS+ is a useful platform for nation branding, brainstorming, and perhaps injecting hope into demoralized, disadvantaged nations in the least developed parts of the world, but it comes with challenges. Some analysts claim that the BRICS countries are “sidelining the existing institutions of global governance,” thereby making “genuinely multilateral cooperation harder.”[9] This may be an overstatement since, with a few exceptions like the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, there is no effective, inclusive multilateral cooperation in the present system to begin with, and BRICS+ does not offer a viable, alternative institutional mechanism either. Contrarily, the group’s consensus-based decision-making scheme is incapable of resolving the most pressing issues in resource governance and geopolitics, say the Israel-Gaza war or the phasing out of coal as the most polluting hydrocarbon fuel. A more plausible argument is that the lack of formal structures and institutional capacity, diverging priorities, and geopolitical hurdles within BRICS+ inhibit its effectiveness.

BRICS+ represents a counterweight to the U.S.-led neoliberal world order but lacks a coherent policy outlook and a shared agenda. While it is true that individual BRICS+ member nations have differentiated comparative advantages and are likely to be viewed favorably as investors in the Global South more generally, as a group, it has a restricted sphere of influence due to economic imbalances and a lack of a coordinating body. In essence, with its present shape and form, it lacks the teeth to turn vision for a unified economic bloc into tangible action.

To support cross-border transactions among member nations, BRICS+ should establish a formal, institutional structure (BRICS+ secretariat) to increase bilateral trade in local currencies and to raise the NDB’s foreign currency reserves. NDB’s loan portfolio of US$32.8 billion is very small by comparison with other Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), such as the World Bank (US$227 billion), and NDB’s portfolio of projects is concentrated in infrastructure and emergency assistance, with other sectors receiving considerably less finance.[10] Policy and funding within the NDB should promote sustainable development of niche clean energy, water, and food security projects.

Also, the much-hyped formation of a common BRICS currency for the eleven strongly diverging, geographically dispersed economies is unfeasible under present conditions. Russia has the strongest incentive to support the creation of an alternative reserve currency and has led the BRICS effort to do so since over half of its foreign exchange reserves have been frozen by Western sanctions since 2022. But the NDB needs a common exchange rate policy, a joint financial infrastructure, and a central bank with larger reserves to support a BRICS+ currency. The generally poor sovereign credit ratings of BRICS+ countries would also be a concern for a reserve currency. In any case, China and India – the two largest economies in BRICS+ – are not in favor of developing a common currency.

As a priority, BRICS+ should address large trade deficits, focus on FDI, technology transfer, and value-added products rather than commodities trade and extractive sectors. Harmonization of customs, transit fees, and taxation within a “BRICS+ trade zone” would be a big step in that direction. The merging of property legislation among BRICS+ countries might also open the door to cross-border transactions, boosting the UAE’s real estate sector and supporting economic growth.[11]

Conclusion

The expansion of BRICS with the inclusion of six new members marks a significant milestone in the organization’s evolution. The 15th BRICS summit’s decision to invite the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Argentina, Ethiopia, and Iran reflects a strategic move towards creating a more influential and diversified coalition, positioning BRICS as a key player in shaping the global economic and geopolitical landscape. With the expanded organization, now known as “BRICS+”, the group not only solidifies its economic strength, comprising a substantial share of global GDP and critical resources, but also reinforces its commitment to fostering a multipolar world order. The move aligns with the growing discontent with the existing international order and presents an alternative platform for emerging nations to address pressing issues such as trade imbalances, income inequality, and currency dominance. As BRICS+ embarks on this new phase, the expectation is that it will leverage its enhanced collective influence to advocate for meaningful reforms in the global political, economic, and financial architecture.

However, challenges accompany the opportunities presented by BRICS+ expansion. The lack of formal structures, institutional capacity, and a shared agenda within the group may hinder its effectiveness in addressing complex global issues. The call for a BRICS+ secretariat and a more coordinated approach to policy-making highlights the need for a stronger organizational framework. Additionally, while the aspiration for a common currency faces practical hurdles, the organization should prioritize addressing trade deficits, promoting sustainable development, and fostering technological collaboration among member nations. In navigating these challenges and capitalizing on the opportunities, BRICS+ has the potential to play a crucial role in reshaping the narrative of global governance, offering a counterweight to established institutions, and promoting a more inclusive and equitable world order.

[1] Joseph Cotterill, “Brics Leaders Invite 6 Nations Including Saudis and Iran to Join Bloc,” Financial Times, August 24, 2023, sec. Emerging markets, https://www.ft.com/content/30f96f4c-e5a6-452c-a283-265c558b0cf2.

[2] “BRICS Economies Now Larger than G7 – Putin — RT Business News,” RT: Russia Today (blog), October 16, 2023, https://www.rt.com/business/585043-putin-brics-g7-purchasing-power/.

[3] Gregory Shupak, “Bloomberg Hits BRICS as US Power Challenged,” FAIR (blog), September 14, 2023, https://fair.org/home/bloomberg-hits-brics-as-us-power-challenged/.

[4] Alan Smith, Keith Fray, and Alec Russell, “The à La Carte World: Our New Geopolitical Order,” Financial Times, August 21, 2023, sec. The Big Read, https://www.ft.com/content/7997f72d-f772-4b70-9613-9823f233d18a.

[5] Nosmot Gbadamosi, “Why Africans Want to Join BRICS,” Foreign Policy (blog), August 23, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/08/23/brics-ukraine-russia-africa-summit-ramaphosa/.

[6] “Fitch Revises New Development Bank’s Outlook to Stable; Affirms at ‘AA,’” Fitch Ratings, May 16, 2023, https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/fitch-revises-new-development-bank-outlook-to-stable-affirms-at-aa-16-05-2023.

[7] Rachel Savage, “‘BRICS Bank’ Aims to Issue First Indian Rupee Bond by October,” Reuters, August 21, 2023, sec. Markets, https://www.reuters.com/markets/brics-bank-aims-issue-first-indian-rupee-bond-by-october-2023-08-21/.

[8] Rachel Savage et al., “‘BRICS Bank’ Looks to Local Currencies as Russia Sanctions Bite,” Reuters, August 10, 2023, sec. Finance, https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/brics-bank-looks-local-currencies-russia-sanctions-bite-2023-08-10/.

[9] Shupak, “Bloomberg Hits BRICS as US Power Challenged,”op. cit.

[10] “New Development Bank: Investor Memo,” Investor Relations (Shanghai, China: New Development Bank, March 2022), https://www.ndb.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Investor-Memo_202203.pdf.

[11] “How Joining BRICS Will Boost UAE’s Different Economic Sectors,” Khaleej Times, August 27, 2023, https://www.khaleejtimes.com/business/how-joining-brics-will-boost-uaes-different-economic-sectors.