If the enemy of my enemy is my friend, what will happen to the ‘friends’ in Syria now that their common enemy, the Assad regime, is no longer? The various opposition elements that coordinated to take down the regime—the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA), the southern armed factions that constituted the Southern Operations Room (SOR), and Hayyat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)—have varying degrees of conflicting interests between them. Now that the common enemy of the Assad regime is no more, what are the prospects of these elements finding a cooperative path forward versus the alternative? Where are the potential fracture points that foreign policymakers should be aware of as they chart their respective roadmaps ahead for engaging in and with the emerging power structure within Syria in order that their engagement is as stability-inducing as possible?

The ‘conflict trap’ model, which holds that war reverses a country’s development, which in turn increases the likelihood of further war, which in turn further reverses a country’s development, has been sufficiently researched to show that, in the first year of peace after conflict, the chances of conflict reoccurring are more than 20 percent.[1] Starting from scratch, as is the case in post-civil war settings like Syria, means a scarcity of resources and a lack of functional, nationally cohesive, governance structures to ensure stability.

Accordingly, the following months are crucial in Syria. They are crucial in terms of the need for foreign actors to understand how to help build and consolidate alignment between the domestic power centers. But they are also crucial in the sense that foreign actors understand the extent of fragility in the domestic Syrian balance of power and the immense dangers of exacerbating this fragility by pursuing their own interests outside of an internationally coordinated and cohesive approach. Such an outcome, and the backsliding into conflict that would follow, would leave everyone worse off, as the last 13 years have shown perfectly.

Granted, there are numerous sources of risk to consolidating stability in Syria outside of just tensions between armed factions. However, given that a consensus amongst interviewees the author spoke with in Syria from late December 2024 to early January 2025 was that the two greatest threats to ongoing stability are Alawi unrest and tensions between the armed factions and HTS, the focus of this piece on the latter is justified to build greater understanding regarding these factions and the power centers they constitute.

This piece will proceed by examining each of the main power centers currently extant in Syria and where their interests and emerging post-Assad patterns of behavior lie vis-à-vis those of the other relevant actors. Aside from HTS, which is the incumbent authority, and the abovementioned SNA (within which, it must be noted, there are significant levels of factionalism), the other power centers include the various armed factions in Syria’s south (which constituted the SOR during the offensive that removed the regime) and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) alongside the Kurdish administration in Syria’s northeast (known as the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, or AANES). The SDF and the AANES, while not a significant part of the effort to overthrow the regime, are nonetheless a major element that impacts the trajectory of stability in Syria moving forward, as the current clashes between it and the SNA show. The piece will conclude with a discussion and recommendations section that outlines how relevant foreign actors should gear their engagement to optimize the cooperation side of this balance and not undermine Syria’s nascent stability, illustrating how this can serve the interests of all.

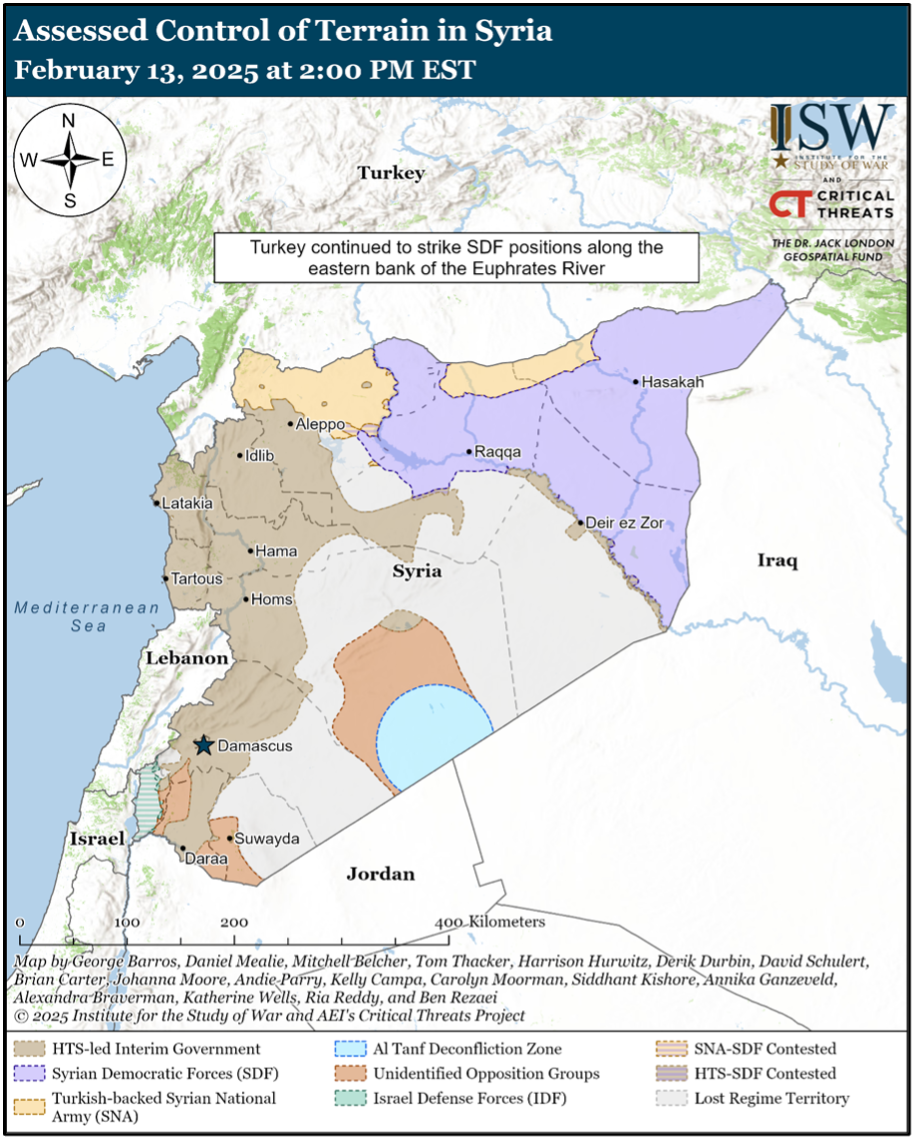

Source: Institute for the Study of War

1) Hayyat Tahrir al-Sham

HTS, with a (conservatively) estimated 30,000 fighters (this number will since have grown seeing as many SDF members have defected to HTS following Assad’s fall),[2] is by far the strongest single armed group compared to the various SNA and southern armed factions,[3] and is also estimated to be stronger than the YPG[4] (the main faction of the SDF, and indeed essentially the faction with which current HTS-SDF negotiations are about given the majority of the remaining SDF members are/were those Arabs that have been deserting in large numbers). Aside from its military superiority, HTS also boasts notably greater governance experience due to its governing entity, the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG), having governed Idlib since 2017 outside of regime control. Even before rising to become the incumbent national authority, HTS also boasted notable economic resources compared to the other groups by virtue of the relatively well-functioning economy it had established in Idlib.

HTS’ leadership of the offensive that overthrew Assad and its greater military and governance experience have so far seen it monopolize Syria’s post-Assad political future. HTS leader Ahmed al-Sharaa has installed a transitional administration, consisting of SSG figures and led by the former SSG Prime Minister Mohammed al-Bashir. This transitional administration has a mandate lasting until March 2025 to implement the processes necessary to establish a technocratic government as of that time.[5] The details surrounding how this government will be established, and how much of a say those outside of HTS will have in its formation, are currently unclear.

HTS has gone to great pains to promote the moderate and inclusive nature of its intended governing nature and objectives, pledging to uphold minority rights, and emphasizing intentions for pluralistic governance through institutions as opposed to Islamist structures. Al-Sharaa’s origin story—a consistent evolution from ideological Islamist beginnings through numerous stages of realignments and separations in the pursuit of consolidating political power within Syria[6]—strongly points to the reality that Sharaa is now driven far more by political power than ideology.[7] Given that, a moderate system is what is most aligned with the diverse society of Syria, much of which would reject an Islamist system, Al-Sharaa’s political pragmatism would point to him pursuing such moderation (it needs to be emphasized, however, that “moderate system” does not necessarily mean liberal democratic). Indeed, so far, HTS has made a concerted effort to reassure minorities like Christians and Druze that HTS is there to help, going as far as to door-knock in Druze and Christian areas to assure them as much[8] (the Druze, located in Suweida governorate, are the key power center in Syria’s south given that Deraa’s factions have already largely submitted to HTS authority).

The consolidated system that Al-Sharaa is likely to push for over the next couple of years is set to involve, on the one hand, a strong presidency (with him as president) in charge of security, foreign relations and the national economy, and on the other hand, a prime ministership (likely with someone from the erstwhile Syrian National Coalition—the previously internationally recognized opposition umbrella body that has just dissolved itself and integrated into the new Syrian state[9]—or a big business individual as prime minister) that oversees more day-to-day bureaucratic-level governance of the country.[10] Al-Sharaa and HTS can’t manage the entire governance system on their own, so this division of power could be how they sustain their authority while also increasing the chances of sanctions being comprehensively lifted.

Nonetheless, the path to this outcome may not be clear for Al-Sharaa. While he holds a certain level of moderate and pluralistic governance ideals, many of the other main power brokers within HTS are the Al-Nusra remnants of the organization. They are largely non-democratic and strongly Islamist in their ideals, and they hold a not insignificant amount of influence over Al-Sharaa.[11] For instance, Al-Sharaa gave these more extreme elements of HTS the judicial and religious administrative offices immediately upon assuming power in December to mollify them due to their dissatisfaction at Al-Sharaa’s espousal of pluralistic intentions for Syria’s governance.[12]

Despite HTS continuing to hold numerous salon gatherings and town halls with all sects and groups to promote its intentions for inclusivity, so far it has not made sufficient tangible actions to back this up. The group has replaced much of Syria’s bureaucracy and all government ministers with their own people, to no small extent due to them not knowing who to trust—a result of HTS having fallen into this leadership position completely unexpectedly.[13] Along with these developments, moves like completely disbanding Syria’s police system in December and delegating policing duties to HTS fighters, mean Al-Sharaa has ground to make up in building confidence across Syria’s population that his declarations of incoming inclusive governance are genuine.

Further demonstrating the trend toward centralization and the yet-to-be-seen inclusivity was the 29 January announcement of Al-Sharaa formally assuming the role of president. Here, he will lead the yet-to-be-appointed transitional government through the up to four-year period he has tabled as the necessary lead-in period to national elections.[14] Al-Sharaa was anointed president on 29 January ostensibly by a portion of the military coalition (HTS, SNA factions, and SOR factions) that constituted the offensive that overthrew Assad in December. However, the full extent to which rebel groups were involved in this anointing process was kept quiet. Nonetheless, it was confirmed that it was, at the least, missing the Druze armed factions, which are key power brokers in Syria’s southwest.[15] Furthermore, it has become apparent that the purpose of this 29 January address was not made clear to many of the armed factions invited before the time, thus its nature duly took them by surprise.[16] Accordingly, it’s unclear that a broad range of factions had a say in the process, which could provide fuel for increased friction later on once tough decisions over Syria’s governance begin to be made and implemented.

2) Syrian National Army and Turkey

The SNA and Turkey are by no means synonymous, and to consider the SNA as merely a set of Turkish mercenaries or direct proxies would be highly fallacious (indeed, the SNA itself is also defined by considerable factionalism).[17] However, when speaking of the different emergent power blocks in post-Assad Syria in the context of this analysis, the SNA and Turkey are sufficiently aligned to speak of them as a general grouping.

The SNA, which receives arms and military support from Turkey, is the armed element of the Syrian Interim Government (SIG), which until the fall of Assad was the leading element of the internationally recognized Syrian opposition. Unlike HTS, the SNA is not a centralized cohesive entity but is instead an umbrella group of more than 40 rebel factions. Faction leaders are typically the primary decision-makers within the SNA, as opposed to the policymakers of the SIG.[18]

Formed in 2017, the SNA’s mandate was to coordinate a panoply of Syrian rebel groups to spearhead Turkey’s counterterror efforts against Islamic State as well as Turkey’s fight against the (Kurdish) People’s Protection Units (YPG), the largest armed group within the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). The SDF is the military element of the AANES, which has governed northeast Syria, also known as Rojava, since 2014, when Kurdish forces reclaimed that territory from the Islamic State.

The SNA and Turkey on one side and the YPG on the other have been in conflict since the year following the SDF’s formation in 2015 due to the strong links between the YPG and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a long-standing key adversary of Turkey, which it designates as terrorists. The downfall of the YPG remains a leading interest of the SNA and Turkey in post-Assad Syria. Turkey also wants to coordinate with the SNA to be able to create a situation in Syria that can ensure the sustainable return of the roughly 3 million Syrian refugees currently in Turkey.

To this end, even as HTS was in the process of leading the offensive that toppled the Assad regime (an offensive indeed coordinated with the SNA), the SNA had simultaneously launched a separate assault on areas held by the SDF in northern Aleppo governorate. This offensive against the SDF and Turkish interests regarding the future of the Kurds in Rojava will be expanded on in the following section, but the reality is that the SDF/AANES future as an autonomous entity within Syria is now incredibly tenuous. Turkey and the SNA, in alignment with HTS on this matter, have the upper hand.

And what about the SNA and Turkey’s stance toward HTS? Regarding Turkey, aside from giving HTS its approval to launch the offensive on 27 November that eventually (and unexpectedly) led to the fall of Assad, they’ve coordinated with HTS and its SSG in Idlib since the establishment of HTS/SSG rule there in 2017. Turkish military and logistical support to HTS over these years has been geared to enable them to repel regime offensives that, if successful, would have led to new influxes of refugees into Turkey.

Aside from enabling HTS to develop into the advanced military entity they now are, this Turkish support for HTS in Idlib indeed saved them from looming destruction by the Syrian regime and the Russian offensive there over 2019-20.[19] Accordingly, Turkey will look to cash in on this debt to shape post-Assad Syria in line with its desires. Here, Ankara wants the SNA to form the core of the new Ministry of Defense and indeed has pushed for this by proposing the establishment of a military council to transition the SNA into a professional military.[20] This is set to become a point of genuine contention between Turkey/SNA and HTS. However, HTS will likely struggle to get all of its own ways due to Turkey being the key international power broker in Syria—Turkey’s National Intelligence Organization, or MIT, alongside various other Turkish counselors, are also the key advisors across all aspects of HTS’ current administration—combined with the extent of SNA influence in key strategic parts of the country.

Regarding the SNA stance toward HTS, the SNA factions that aren’t originally from Aleppo governorate (i.e., the governorate where the SNA, as an umbrella grouping, has been situated since its inception) have now settled back in their hometowns in Homs, Hama, Rural Damascus and Deir ez-Zor governorates, where their numbers and support are set to increase. Most of the SNA factions, however, are originally from Aleppo governorate (particularly Azaz, Afrin and Jarablus), and it looks like HTS will not be getting in the way of these factions establishing influence in their home territories there and indeed over Aleppo city. HTS, which is significantly outweighed by the SNA factions in the Aleppo governorate,[21] is largely conceding the Aleppo governorate to these factions and Turkish influence while it goes about instead consolidating influence over the governorates further south.[22]

But this aforementioned latitude is so far not being offered to those SNA factions that have resettled in the other abovementioned governorates, potentially portending a difficult future. It must be acknowledged that Hama governorate is not looking like it’ll become too problematic for HTS—prominent SNA faction leader Mohammed al-Jassim, otherwise known as Abu Amsha, has been appointed to the rank of Major General by HTS, taking command of a Hama-based division of the under-formation new Syrian army.[23] However, many of the SNA factions in Homs, Deir ez-Zor and Rural Damascus governorates have not integrated with the new Ministry of Defense. If these factions feel that HTS is not affording them a sufficient level of influence in their respective regions in the ongoing attempted integration process of all armed factions, then this could prove problematic for HTS authority, especially as Turkey could apply pressure in support of these factions as part of its effort to consolidate influence over the direction of Syria’s military.

Jaish al-Islam (the most organized faction within the SNA) could be a prominent example if such a trajectory materializes, with the faction having resettled itself in Douma in Rural Damascus and begun rejuvenating.[24] Jaish al-Islam and other SNA factions in the Damascus countryside have long-standing ill-feeling toward Al-Sharaa due to his extremist past and deem his ascension to power over the past weeks to be unjustified and a case of merely being in the right place at the right time.[25] One example of the difficult relationship between the group and HTS was the latter’s detention of Jaish al-Islam’s security chief, Saadou al-Ghazawi, in a raid on 26 January due to his refusal to dissolve the faction.[26]

It is important to emphasize that none of these armed factions want conflict and indeed currently see stability as in their interests vis-à-vis maintaining support from their respective communities.[27] However, many of these factions don’t accept that HTS is the state—they consider HTS as just another one of the factions (and indeed a faction around 25% of which are foreign fighters).[28] Accordingly, despite a 24 December agreement between HTS and many SNA and some southern factions to “integrate” them into the new Syrian armed forces,[29] with 60 more factions joining this supposed integration agreement on 19 January[30] and another 18 more factions on 29 January,[31] many of these factions have only ‘integrated’ into the Ministry of Defense while still maintaining their previous form and structure[32] (i.e., they could retain their ability to act as independent, autonomous units if they feel their interests require it).

Despite this ongoing potential for tensions between SNA factions and HTS, there are factors working against these escalating to conflict. One of these is the reality that SNA factions, for the purposes of sustaining their authority in their respective locales, will need the funding that would come through the future reconstruction process. Al-Sharaa and HTS will inevitably be the gatekeepers of this reconstruction funding, and Al-Sharaa will likely pressure SNA factions to largely demilitarize and integrate into the Ministry of Defense in exchange for the economic and financial authority and legitimacy in their respective locales that would be afforded by this reconstruction money.[33] This future equation presents a more compelling set of incentives to what currently exists for the SNA factions in their calculus regarding integration.

3) Syrian Democratic Forces and the Kurdish-administered northeast

The SDF is an umbrella organization of multiple armed groups, but, as mentioned, the YPG is the largest amongst them. Significantly, while the YPG (a Kurdish group) is the largest single group within the SDF, most of the SDF is not Kurdish, instead being mostly Arab.[34] Another important element to outline within the AANES is the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the Kurdish political party that is attached to the YPG and is the leading political entity within the AANES.

Turkish forces (supported by the rebel groups that constitute the SNA) carried out three separate large-scale military operations in Syria’s north between 2016-19 (Operation Euphrates Shield, Operation Olive Branch, and Operation Peace Spring) in an attempt to undermine the SDF and create buffer zones between it and Turkey. Despite Turkish grievances regarding the YPG/SDF remaining following these operations, Turkey (and the SNA) in recent years had largely withheld attempts to make further incursions against the SDF and AANES. A key reason for this in the last two years particularly was Ankara’s desire to negotiate agreements with the Assad regime to enable the sustainable return of Syrian refugees from Turkey to Syria. These efforts were not progressing due to Assad’s insistence that Turkey first withdraw its forces from northern Syria. Accordingly, if Turkey had expanded its military operations against the SDF, then this (already unpromising) negotiating effort would have been completely dead in the water.

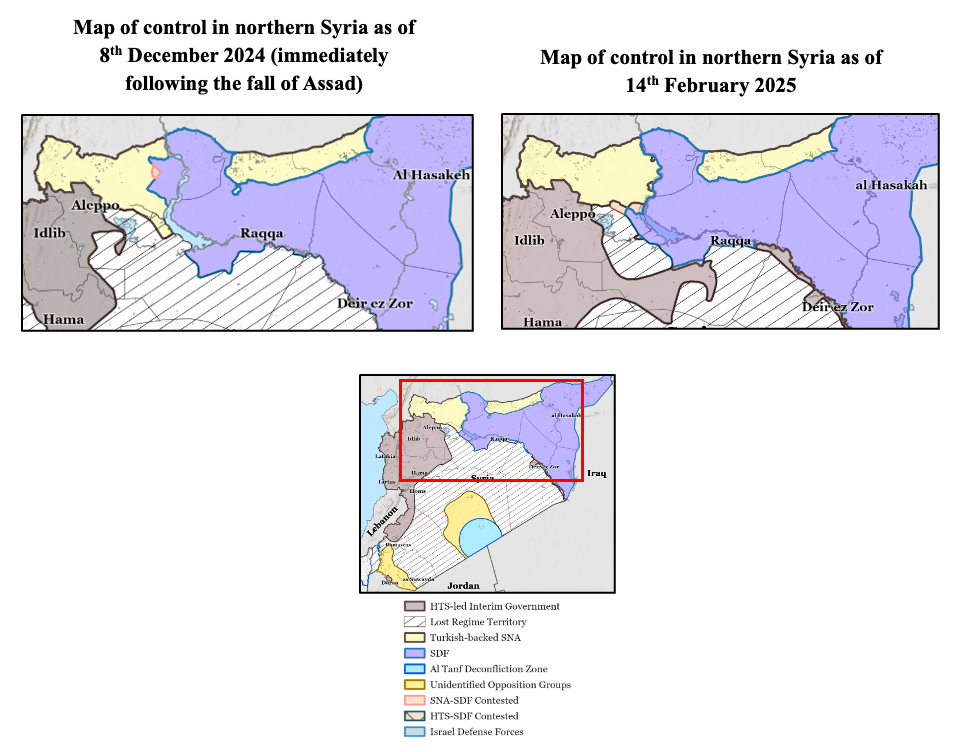

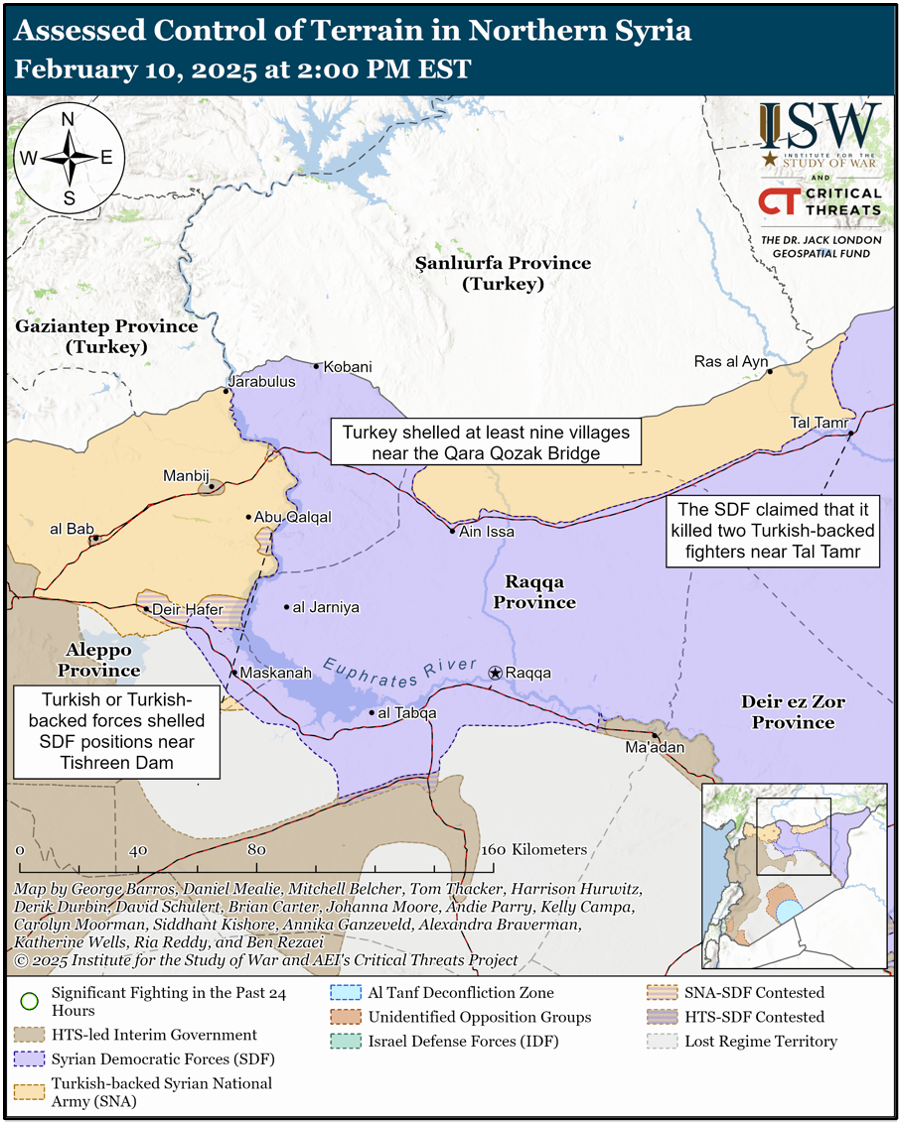

Source: Institute for the Study of War

Now that the Assad regime is no more, however, Turkey is no longer constrained in this way. And Ankara has already taken advantage. The SNA, aided by significant Turkish artillery and air support, seized the strategically important cities of Manbij and Tel Rifaat from the SDF over early-mid December. On top of these territorial changes, Turkish and further SNA troops have been mobilizing along Kobane, Ain Issa and Tal Tamr (i.e., the existing line of control between the Turkish-occupied part of northeast Syria and AANES territory) from late December through January in preparation for what seems a likely assault on SDF/AANES control of Raqqa governorate.[35] This increasingly precarious territorial situation facing the SDF has been compounded by mass defections from the group by its Arab members as they flock to join their Arab kin in HTS and the SNA.[36] Additionally, the SDF is also now in conflict with Arab tribal forces led by Sheikh Ibrahim al-Hifl in Deir ez-Zor governorate.[37]

Source: Institute for the Study of War

Accordingly, the SDF and AANES have been left urgently attempting to negotiate with Turkey and HTS to preserve their autonomy.[38] SDF negotiation demands have centered on agreeing to integrate into the new Syrian army if the SDF is able to do so by integrating in its current form and remaining deployed in northeastern Syria, coupled with maintaining a level of autonomy as part of a new decentralized Syrian political system as well as partial control over oil revenues in the northeast.[39] The conditions pertaining to autonomy and decentralization have been expressly outlined as intolerable by HTS, which demands that all of Syria be part of a centralized national system. The SDF’s negotiation strategy has extended to building a quasi-alignment with the Druze in Suweida, with the political wing of the SDF (the Syrian Democratic Council) and Druze leader Sheikh Hikmat al-Hajri advertising their shared stance that a “comprehensive transitional government” and an end to all fighting in Syria must be achieved before they agree to hand over their weapons to the Syrian state, which itself should embody a decentralized structure.[40]

Since opening negotiations with HTS at the end of December, the SDF has barely moved from its original negotiating demands, and there are no signs this will change.[41] As a result of this intransigence, HTS is now hinting that it may take military action itself against the SDF to force them to disarm.[42] Following this warning, HTS forces have deployed to Rusafa,[43] just south of SDF territory in Raqqa governorate, giving the potential for HTS and the SNA/Turkey to coordinate in a pincer movement, with the former pushing up toward the strategically key Raqqa city from the south while the latter pushes toward the city from the north and west. Given the extensive defections the SDF has suffered since 8 December combined with now being stretched thin due to fighting on multiple fronts, if HTS, the SNA and Turkey were to proceed with such an offensive, it is likely that the SDF would be overcome.

The U.S., which has backed the SDF since its inception, has shown its unwillingness to bring the sort of military support to bear to deter Turkish/SNA designs against the SDF. President Donald Trump doesn’t have any ideological commitment to the Kurds, as displayed during his first term in office. Trump’s only major interest connected to the Kurds is their role in suppressing an ISIS resurgence in the northeast of Syria, but Turkey has detailed plans for taking over this remit in the event of an SDF dissolution. There is little evidence that Trump would oppose such a plan. Accordingly, the looming reality is that the PYD/AANES project in Rojava seems to be on its last legs, and it will likely instead be absorbed, as Turkey desires, into the Syrian national project, and control of the northeast’s oil fields (the key source of YPG revenue) coming under the control of Damascus. This will all mean YPG/PYD strength in the northeast diminishes to an insignificant level (at least vis-à-vis Turkish interests).

Where are the Kurds under this new reality? In the likely process of the absorption of the northeast into the national Syrian project that emerges over the coming months, HTS has already stated its openness to granting Kurdish-majority areas in the northeast bureaucratic control over their local affairs at the municipal governance level,[44] akin to the form of the local councils currently present there that are the primary decision-makers over matters of day-to-day life. However, an autonomous Kurdish region, à la the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq, or indeed à la the current AANES, will be no more,[45] and the SDF would likely be disbanded and Kurds offered integration into the national army.[46] Turkey, in line with its previously stated desires, will also push for the Kurds to leave the Arab parts of Rojava and relocate to the traditional Kurdish territories there, in other words, shrinking the territory that is Kurdish inhabited.

4) Southern armed factions

Rebel factions in southern Syria (Suweida and Deraa governorates) had been inactive since 2018 when they were coerced into ‘reconciliation agreements’ with the regime. However, several days into the HTS-initiated offensive that began on 27 November last year, a coalition of several of these southern factions was announced, called the Southern Operations Room (SOR).

This coalition consisted of around 25 opposition groups originating from the Druze-majority Suweida governorate and the Sunni-majority Deraa governorate.[47] The primary Deraa entities in question are the Central Committee and the Eighth Brigade, and the key Suweida entities are the Sheikh al-Karama Forces, Liwa al-Jabal, Ahrar al-Jabal, and Rijal al-Karama Movement,[48] the latter being the most prominent. While each entity has its own leadership, the titular leader of the SOR has been Ahmed al-Awda (the head of the Eighth Brigade).

The SOR was reportedly formed in collaboration with HTS in the months leading up to the offensive that toppled the Assad regime to coordinate the former’s application of pressure on the regime from the south while the latter would apply pressure from the north.[49] The offensive unfolded far better than hoped, and it manifested with an unpredicted speed in which the SOR was indeed the first to enter and secure Damascus just days into the effort (although control of Damascus was subsequently handed to HTS).

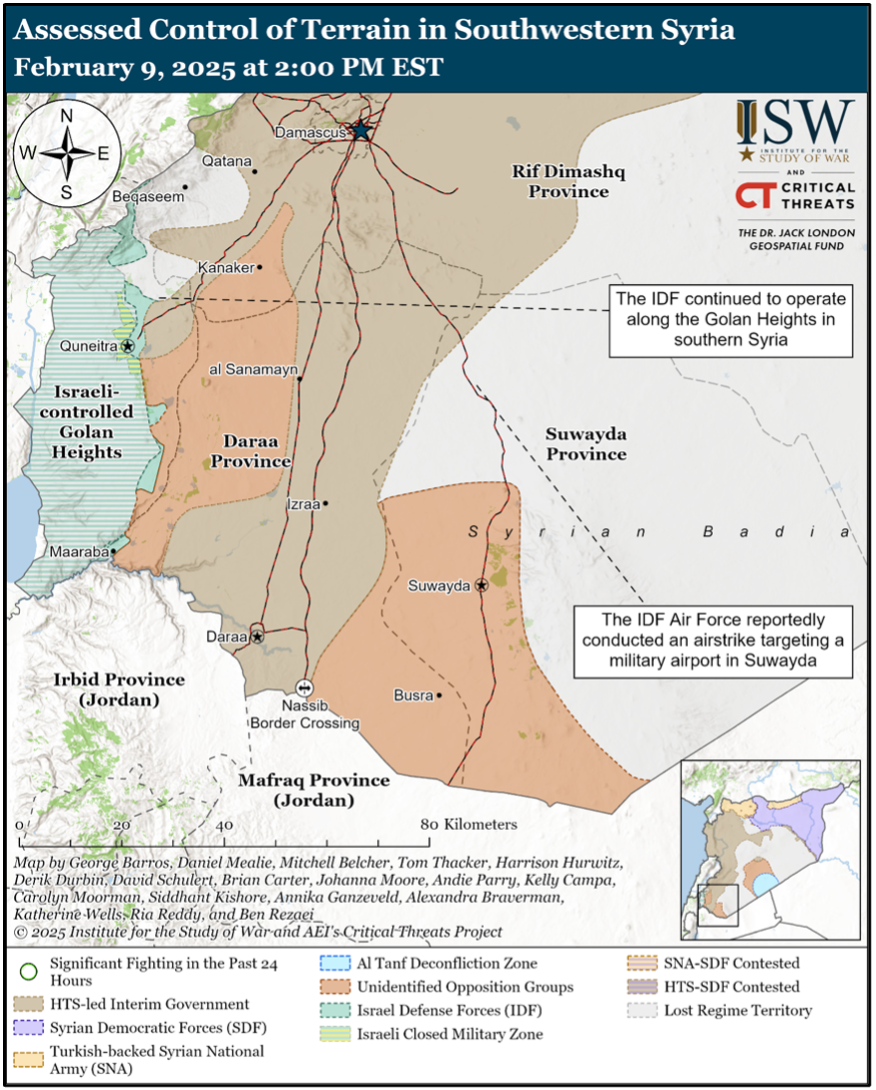

Source: Institute for the Study of War

With the offensive over and the regime no longer, the SOR has inevitably decreased as a cohesive grouping. While erstwhile SOR leader, Al-Awda, who is now largely based in Jordan, has been spending most of his time since the fall of Assad shuttling between Jordan, Turkey and Gulf states looking to gauge the temperature of these external players (multiple of which have provided support to his Eighth Brigade in the past),[50] his leadership lacks legitimacy amongst much of Syria’s south due to his previous collusion with Russia over the formation of the Eighth Brigade,[51] and he would be unable to marshal widespread committed support.

Given that, what are the interests of the main southern factions going forward? The vast majority of the factions do not harbor Islamist views (indeed many of them are Druze), and they are primarily focused on securing their own communities.[52] HTS has been pushing to consolidate control in Deraa by installing HTS figures in governorate-level administrative civilian positions.[53] This has been buttressed by HTS assuming control of the key southern border crossing with Jordan in Deraa (Jaber Crossing), thus resulting in HTS exercising significant influence over eastern Deraa, as alluded to in the above map.

Despite evident disquiet by elements in Deraa at this trajectory, this is unlikely to conflagrate too substantially. There is internal discord in the Deraa portion of the SOR—for instance, Awda’s Eighth Brigade in east Deraa has been in power tussles with the Central Committee in west Deraa.[54] Indeed, as alluded to above, Al-Awda is more of a patron than a dominant leader of the SOR, and he has spread too thin dealing with internal power dynamics to concertedly resist HTS’ consolidation of authority.

Regardless, Al-Awda largely takes his instructions from various regional states, which have harbored and/or supported a notable portion of the southern rebel group leadership since the groups submitted to the Assad regime in 2018. And currently, these states have instructed al-Awda not to turn against HTS for fear of destabilizing the nascent post-Assad system.[55] Furthermore, Al-Awda and much of the southern rebel leadership hold aspirations for becoming members of parliament in the new Syrian government. Additionally, most of them are business leaders in their communities first, and militia figures second, and they know Al-Sharaa is a pro-business figure, as demonstrated by his neoliberal governance of Idlib. Taken together, this means most of these rebel leaders are keen to cash in on the new Syrian system yet to emerge, as opposed to flipping the apple cart.[56]

A caveat needs to be placed here in that the Druze factions in Suweida are exerting pressure on HTS regarding the manner in which they integrate into the new Syrian national system. The reason the Druze factions were noticeably absent at the coalition gathering on 29 January to inaugurate Al-Sharaa as President, mentioned above, was due to their refusal of the invitation.[57] While HTS has been moving quite freely through Deraa, an effort by HTS forces to move through Suweida in early January was turned back by the Rijal al-Karama militia.[58] While this was a non-violent event, it nonetheless displays the greater level of assertiveness the Druze are sustaining in the protection of their authority in the governorate.

Much of the Druze, particularly through leader Sheikh Hikmat al-Hajri and the Rijal al-Karama militia, are refusing to hand over their weapons to HTS on the grounds that since there isn’t a state at the moment, no source of protection would exist for them.[59] Druze factions, and indeed Sheikh al-Hajri, have expressed eagerness to join the new Syria national project, but they have largely been insisting that this national project is decentralized in nature, affording the Druze a high level of autonomy over their affairs.[60] A genuinely representative transitional government process must be secured, and the foundations for an inclusive state established, before the Druze leadership will demilitarize, at least according to their current stance.[61] Nonetheless, negotiations between the Druze and HTS are continuing.[62]

Looking ahead: Implications for relevant foreign states

While, as illustrated, there are numerous points of contention between the emergent centers of power in post-Assad Syria, there is no certainty of genuine rebellion against HTS by the SNA or southern factions. Rebel leaders in post-war Syria are dependent on public opinion for their continuity, and the blowback upon them, if they were to be the ones to ruin nascent post-Assad stability is a risk they will likely be highly averse to.[63]

The likely reality is that HTS will push to establish a form of soft authoritarianism, whereby respect for Syria’s ethnic and socio-cultural diversity is implemented, but where political power is more so centralized by current HTS elements than it is dispersed.[64] But, in pursuit of this, HTS is clearly not strong enough to start taking on multiple SNA and SOR factions on its own, and it is also not in the interests of other factions to be too assertive. Accordingly, the manner in which HTS pursues this centralization will be a delicate one, with a level of measured pushback from Druze and potentially some of the major SNA factions (largely concerning maintaining a level of security autonomy for the foreseeable future until a legitimate state is established) set to make this centralization a circuitous and protracted process. While HTS could join forces with the SNA and Turkey to militarily force the Kurds to integrate into the national Syrian project, such dominant coalitions like these are highly unlikely to be able to be formed to coerce southern factions or SNA factions given the lack of sufficiently aligned interests toward such an end.

In terms of other threats to Syria’s nascent stability, what about the potential intervention of key foreign states, which was indeed the central cause of the sustenance of the civil war since its early years? In mid-December, the foreign ministers of Jordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Egypt, Bahrain, Qatar, Turkey, the UAE, the U.S., the UK, the EU, Germany and France met in Jordan to agree to the Aqaba Declaration, which essentially affirmed that all members want to work with, as opposed to against, the current authority in Syria to achieve the change Syria needs. This level of alignment is nascent, however, and highly rudimentary. Therefore, work must be done immediately to build a granular collective understanding amongst these members regarding the governance and stability risks and exigencies (like those discussed in this insight) in Syria. The aim would then be to establish an institutionalized framework from this foundation of the Aqaba Declaration to be able to bring appropriate coordinated influence to bear on ensuring policy directions that enhance rather than undermine the extant level of stability outlined above.

Such an institutionalized framework (built on a shared vision, understanding, and plan), and its dynamic operation, will also be key to ensuring regional states don’t lose faith in the importance of achieving the necessary change in Syria by working with the nascent system, as opposed to backing different power blocks in the country vis-à-vis others in a zero-sum manner. It will furthermore ensure an effective means by which regional states can work out any differences regarding Syria together, as opposed to deciding to pursue their own individual conflicting agendas.

The emerging system in Syria is one in which regional states in particular (aside from the Iranian regime) could see their interests served, whether that pertains to regional economic corridors and integration, further momentum for the Abraham Accords (Al-Sharaa may well see a path for long-term security in joining the Accords at an appropriate point), sustainable refugee return, ending the captagon trade, or otherwise. Therefore, these states shouldn’t feel the need to back different internal power blocks vis-à-vis the others before Syria has even had a chance to get back on its feet.

The Islamist roots of Al-Sharaa and HTS and the worry that the new Syrian government would espouse a strong Islamist orientation, are major concerns shared by numerous regional states. The fact that several armed factions as well as much of the Syrian population, particularly in ideologically moderate and culturally diverse urban centers like Damascus, eschew Islamist governance means the space for implementing such a governance system, particularly in a comprehensive form, is limited. Furthermore, many have raised concerns that Turkey, the emergent main power broker in Syria, might have interests in engendering an Islamist form of government in Syria. But Turkish Islamism is of a notably different, and milder form, and Ankara would not be interested in supporting the form of Arab Islamism in Damascus that those with concerns might be wary of.

Concomitant to the above-mentioned work of the coordinated framework of regional and international partners could be simultaneous aid from regional partners in supporting the development of Syrian civil society as a check and balance for the Syrian government going forward. A diverse, robust civil society would also be an even greater barrier to any potential for comprehensive Islamist governance. Funding the establishment of media outlets (in the manner of Qatar-funded Syria TV, for instance), think tanks, and opinion polling infrastructure in Syria can help ensure the health of a pluralistic and inclusive Syria moving into the future. HTS is currently openly showing interest in research institutes (of no particular inclination) and similar being established in the country,[65] so there is a prime window for external assistance to begin assisting the development of this civil society ecosystem.

To end, and in returning to the opening reference to the ‘conflict trap’—it takes on average 18 years for countries to properly escape such a cycle.[66] In Syria, it is imperative for all concerned parties, domestic and foreign, to gear policy deftly so as not to make escaping that trap any harder than it already will be.

[1] Joan Margalef and Hannes Mueller, “Exiting the conflict trap,” Barcelona School of Economics, February 14, 2024, https://focus.bse.eu/exiting-the-conflict-trap/.

[2] Lars Hauch and Malik al-Avdeh, “The quasi-coup Assad is gone but the deep state lives on – Syria in Transition Issue 19,” Syria in Transition, December 16, 2024, https://mcusercontent.com/d757b1f58c4239e593b6f47cd/files/db1d0b48-206d-b6da-0f4f-6d619b710679/SiT_Issue_19_December_2024.pdf.

[3] “Who are Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and the Syrian groups that took Aleppo?,” Al Jazeera, December 2, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/12/2/hayat-tahrir-al-sham-and-the-other-syrian-opposition-groups-in-aleppo.

[4] European Union Agency for Asylum, “Syrian Democratic Forces and Asayish,” European Union Agency for Asylum, September 2020, https://euaa.europa.eu/country-guidance-syria/12-syrian-democratic-forces-and-asayish.

[5] Lars Hauch and Malik al-Abdeh, “The quasi-coup Assad is gone but the deep state lives on – Syria in Transition Issue 19,” Syria in Transition, December 16, 2024, https://mcusercontent.com/d757b1f58c4239e593b6f47cd/files/db1d0b48-206d-b6da-0f4f-6d619b710679/SiT_Issue_19_December_2024.pdf.

[6] Dalia Ghanem, “Why Jihadist Groups Never Really Die,” Middle East Council on Global Affairs, December 16, 2024, https://mecouncil.org/blog_posts/why-jihadist-groups-never-really-die/.

[7] Al Jazeera and Patrick Haenni, “Patrick Haenni interview – Syria: The rise of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham,” Al Jazeera, December 23, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F93fJi_YMus.

[8] Author’s interview with Nazir Salem, Damascus, January 5, 2025; Author’s interview with Hazem Youness, online, January 15, 2025.

[9] SANA, “President al-Sharaa meets with delegations of Syrian Negotiation Commission and National Coalition,” SANA, February 12, 2025, https://sana.sy/en/?p=346669.

[10] Author’s interview with Malik al-Abdeh, Damascus, January 3, 2025; Charles Lister, “10 Key Takeaways from Syria,” Syria Weekly, February 10, 2025, https://www.syriaweekly.com/p/10-key-takeaways-from-syria.

[11] Author’s interview with Tarek Hamdan, Damascus, December 29, 2024; Author’s interview with Rabie Munther, Damascus, January 1, 2025.

[12] Author’s interview with Rabie Munther, Damascus, January 1, 2025.

[13] Author’s interview with Nazir Salem, Damascus, January 5, 2025.

[14] Timour Azhari and Tom Perry, “Syria’s Sharaa declared president for transition, consolidating his power,” Reuters, January 30, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/syrias-leader-sharaa-named-president-transitional-period-state-news-agency-says-2025-01-29/.

[15] Christina Goldbaum, “Syria’s New President Pledges Unity in First Address,” New York Times, January 30, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/30/world/asia/ahmed-al-shara-syria-president.html.

[16] Charles Lister, “10 Key Takeaways from Syria,” Syria Weekly, February 10, 2025, https://www.syriaweekly.com/p/10-key-takeaways-from-syria.

[17] Ömer Özkizilcik, “The Syrian National Army (SNA): Structure, Functions, and Three Scenarios for its Relationship with Damascus,” The Geneva Centre for Security Policy, October 2020, https://dam.gcsp.ch/files/doc/sna-structure-function-damascus.

[18] Rayhan Uddin, “The Syrian National Army: Rebels, thugs or Turkish proxies?,” Middle East Eye, December 7, 2024, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/who-are-syrian-national-army.

[19] William Christou, “Syrian rebels reveal year-long plot that brought down Assad regime,” The Guardian, December 13, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/dec/13/syrian-rebels-reveal-year-long-plot-that-brought-down-assad-regime.

[20] Author’s interview with Malik al-Abdeh, online, December 20, 2024.

[21] Author’s interview with Malik al-Abdeh, online, December 20, 2024.

[22] Author’s interview with Malik al-Abdeh, online, February 11, 2025.

[23] Annika Ganzeveld et. al, “Iran Update, February 3, 2025,” Critical Threats, February 3, 2025, https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/iran-update-february-3-2025.

[24] Lars Hauch and Malik al-Avdeh, “The quasi-coup Assad is gone but the deep state lives on – Syria in Transition Issue 19,” Syria in Transition, December 16, 2024, https://mcusercontent.com/d757b1f58c4239e593b6f47cd/files/db1d0b48-206d-b6da-0f4f-6d619b710679/SiT_Issue_19_December_2024.pdf.

[25] Author’s interview with Malik al-Abdeh, online, December 20, 2024.

[26] Charles Lister, “Syria Weekly: Jan 21-28, 2025,” Syria Weekly, January 28, 2025, https://www.syriaweekly.com/p/syria-weekly-jan-21-28-2025.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Author’s interview with Anas Joudeh, Damascus, January 1, 2025; Author’s interview with Tarek Hamdan, Damascus, December 29, 2024.

[29] Hélène Sallon, “Syria’s new government negotiates the disbanding of armed groups,” Le Monde, December 26, 2024, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2024/12/26/syria-s-new-government-negotiates-the-disbanding-of-armed-groups_6736461_4.html.

[30] Siddhant Kishore et. al, “Iran Update, January 19, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, January 19, 2025. https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-january-19-2025.

[31] Oula Rifai, “Syria and the New Era: A Tale of Two Speeches,” Centre for Syrian Studies – University of St Andrews, January 31, 2025, https://css.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/2025/01/31/syria-and-the-new-era-a-tale-of-two-speeches/.

[32] Author’s interview with Malik al-Abdeh, online, February 11, 2025; Carolyn Moorman et. al, “Iran Update, February 6, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, February 6, 2025. https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-february-6-2025.

[33] Author’s interview with Malik al-Abdeh, Damascus, January 3, 2025.

[34] Shelly Kittleson, “Syria Defence Minister to The New Arab: Above all Syria wants peace,” The New Arab, February 3, 2025, https://www.newarab.com/news/syria-defence-chief-new-arab-above-all-we-want-peace.

[35] Annika Ganzeveld et. al, “Iran Update, January 10, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, January 10, 2025; Kelly Campa et. al, “Iran Update, January 28, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, January 28, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-january-28-2025.

[36] Lars Hauch and Malik al-Avdeh, “The quasi-coup Assad is gone but the deep state lives on – Syria in Transition Issue 19,” Syria in Transition, December 16, 2024, https://mcusercontent.com/d757b1f58c4239e593b6f47cd/files/db1d0b48-206d-b6da-0f4f-6d619b710679/SiT_Issue_19_December_2024.pdf.

[37] Carolyn Moorman et. al, “Iran Update, January 21, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, January 21, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-january-21-2025.

[38] Amberin Zaman, “Turkey-backed Syrian factions end US-mediated ceasefire with Kurdish-led SDF,” Al-Monitor, December 16, 2024, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2024/12/turkey-backed-syrian-factions-end-us-mediated-ceasefire-kurdish-led-sdf.

[39] Siddhant Kishore et. al, “Iran Update, January 19, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, January 19, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-january-19-2025; Kelly Campa et. al, “Iran Update, January 15, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, January 15, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-january-15-2025; Siddhant Kishore et. al, “Iran Update, January 27, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, January 27, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-january-27-2025.

[40] Syrian Democratic Council, “MSD meets Sheikh Al-Hajri in Sweida and discusses Syria’s future and political solution paths,” Syrian Democratic Council, January 28, 2025, https://m-syria-d.com/?p=21119; suwayda24, “Urgent | The spiritual leader of the Druze Unitarian Muslims, His Eminence Sheikh Hikmat Al-Hijri,” X.com, December 19, 2025, https://x.com/suwayda24/status/1869503977483579588; Asharq News, “قائد “قسد” لـ”الشرق”: اللامركزية الخيار الأنسب لسوريا,” Asharq News, January 15, 2025, https://asharq.com/politics/113001/%D9%82%D8%B3%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%B2%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AE%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%86%D8%B3%D8%A8-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A7/.

[41] Siddhant Kishore et. al, “Iran Update, January 27, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, January 27, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-january-27-2025.

[42] AFP, “Syria minister says open to talks with Kurds, but ready to use ‘force’,” RFI, January 22, 2025, https://www.rfi.fr/en/middle-east/20250122-syria-minister-says-open-to-talks-with-kurds-but-ready-to-use-force.

[43] Kelly Campa et. al, “Iran Update, January 23, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, January 23, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-january-23-2025.

[44] Kelly Campa et. al, “Iran Update, January 28, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, January 28, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-january-28-2025.

[45] Karwan Faidhi Dri, “Syria appoints defense minister opposing federalism for Kurds,” Rudaw, December 22, 2024, https://manage.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/syria/22122024.

[46] Johanna Moore et. al, “Iran Update, December 22, 2024,” Institute for the Study of War, December 22, 2024, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-december-22-2024.

[47] William Christou, “Syrian rebels reveal year-long plot that brought down Assad regime,” The Guardian, December 13, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/dec/13/syrian-rebels-reveal-year-long-plot-that-brought-down-assad-regime.

[48] Boaz Shapira, “Rebel factions in southern Syria – Southern Operations Room (SOR),” Alma, December 19, 2024, https://israel-alma.org/rebel-factions-in-southern-syria-southern-operations-room-sor/; Charles Lister, “10 Key Takeaways from Syria,” Syria Weekly, February 10, 2025.

[49] William Christou, “Syrian rebels reveal year-long plot that brought down Assad regime,” The Guardian, December 13, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/dec/13/syrian-rebels-reveal-year-long-plot-that-brought-down-assad-regime.

[50] Author’s interview with Malik al-Abdeh, online, December 20, 2024; Author interview with Malik al-Abdeh, Damascus, January 3, 2025.

[51] Author’s interview with Jordan based Syria researcher (anonymity requested), online, January 21, 2025.

[52] Alma Research and Education Center, “Rebel factions in southern Syria – Southern Operations Room,” Alma Research and Education Center, December 19, 2024, https://israel-alma.org/2024/12/19/rebel-factions-in-southern-syria-southern-operations-room-sor/.

[53] Etana Syria, “Syria Update #11: 17 December,” Etana Syria, December 17, 2024, https://etanasyria.org/syria-update-11-17-december/; Alma Research and Education Center, “Rebel factions in southern Syria – Southern Operations Room,” Alma Research and Education Center, December 19, 2024, https://israel-alma.org/2024/12/19/rebel-factions-in-southern-syria-southern-operations-room-sor/.

[54] Author interview with Malik al-Abdeh, online, December 20, 2024.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Charles Lister, “10 Key Takeaways from Syria,” Syria Weekly, February 10, 2025, https://www.syriaweekly.com/p/10-key-takeaways-from-syria.

[58] “Druze militias deny HTS fighters access to Suwayda: Reports,” Rudaw, January 1, 2025.

[59] Author’s interview with Anas Joudeh, Damascus, January 1, 2025.

[60] Dilkhwaz Mohammed, “Syria’s Druze refuse to lay down arms amid uncertain future,” Rudaw, January 4, 2025, https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/syria/04012025; “Druze militias deny HTS fighters access to Suwayda: Reports,” Rudaw, January 1, 2025, https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/syria/01012025.

[61] Ruth Michaelson and Obaida Hamad, “‘We will keep protesting’: Druze minority demands a voice in new Syria,” The Guardian, January 30, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jan/30/syria-druze-minority-protests-militia-suwayda; “Druze militias deny HTS fighters access to Suwayda: Reports,” Rudaw, January 1, 2025, https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/syria/01012025.

[62] Siddhant Kishore et. al, “Iran Update, February 10, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, February 10, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iran-update-february-10-2025.

[63] Author’s interview with Malik al-Abdeh, online, December 20, 2024.

[64] Author’s interview with Malik al-Abdeh, online, December 20, 2024; Author’s interview with Anas Joudeh, Damascus, January 1, 2025.

[65] Multiple conversations had by the author while in Damascus, December 2024 to January 2025.

[66] Hannes Mueller, “Caught in a Trap: Simulating the Economic Consequences of Internal Armed Conflict,” Barcelona School of Economics, September 2023, https://bse.eu/research/working-papers/caught-trap-simulating-economic-consequences-internal-armed-conflict.