Air power projection from the sea has historically been a specialized area in naval warfare, reserved for nations capable of building aircraft carriers and sustaining them on extended missions away from their home ports. Due to significant operational crew requirements, technological sophistication, and high procurement and maintenance costs associated with aircraft carriers, many small and mid-sized nations opted to develop a modest-sized fleet of surface combatants rather than investing in carriers. However, the groundbreaking impact of robotic technology in warfare, particularly through the fast-paced proliferation of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), has substantially reduced crew needs, financial expenses, and risk exposures, thereby broadening the range of countries pursuing UAV-carrying capabilities. As a result, what was once a capability reserved for global naval powers is now within reach of emerging and middle-tier maritime forces. This impacts the balance of power and shifting geopolitical dynamics on a regional scale. Portugal, Iran, and Türkiye are among the nations seizing this opportunity, leveraging automation to redefine their naval strategies and expand their maritime reach. This insight explores each case and examines how these countries are integrating UAV-carrying platforms into their naval forces, assessing the strategic, operational, and technological implications of this shift in maritime power projection.

First Case: Portugal

“We are marking a point of no return towards modernity,”[1] said the former Portuguese Navy’s Chief of Staff, Admiral Henrique Gouveia e Melo, during the signing ceremony to procure the Navio da República Portuguesa (NRP) Dom João II multi-purpose support ship (MPSS). On 24 November 2023, the Portuguese Navy contracted to the Dutch defense conglomerate Damen Shipyards Group for the design, construction, and equipment of a state-of-the-art multi-function ship. Named after the 15th-century Portuguese King who revamped the country’s maritime exploration thrust, the NRP Dom João II is poised to become the Portuguese naval force’s flagship. This multi-purpose vessel “materializes the vision of developing a holistic, technologically advanced, disruptive, and robotized Navy,”[2] Admiral Gouveia e Melo continued.

While shipyard works are proceeding per schedule, with Damen holding a joint steel cutting and keel laying ceremony in Galati, Romania, in early October 2024,[3] the MPSS project began in 2022. The NRP Dom João II is financed by the European Union’s (EU) Recovery and Resilience Facility, part of the Next Generation EU economic recovery package designed to support the member states in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. The MPSS has an estimated cost of €132 million and is expected to enter service in the second half of 2026.[4]

Weighing 7,000 tons, the NRP Dom João II will be the largest vessel in the Portuguese Navy’s fleet. Although its precise range is still unclear, similar ships in its class have an endurance of around 45 days and a range of approximately 10,000 nautical miles at a cruising speed of 15 knots. These capabilities will enable the ship to operate in distant locations for extended periods, making it well-suited for long-duration expeditionary missions, from peacetime to combat and disaster relief operations. With a crew of 48, the 107-meter vessel can also accommodate 42 scientific personnel and temporarily house up to 100 people.[5]

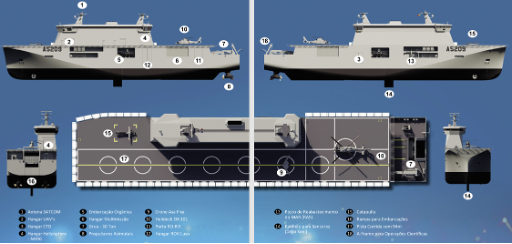

Figure 1: NRP D. JOÃO II’s Operational Profile

Source: Revista de Armada, https://www.marinha.pt/conteudos_externos/Revista_Armada/PDF/2024/RA_592.pdf.

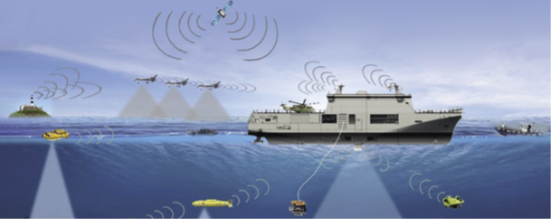

The NRP Dom João II will serve as a hybrid naval asset, blending conventional landing platform dock (LPD) features with cutting-edge capabilities as a mother ship for unmanned systems.

On the one hand, the ship will feature a 94-by-11-meter flight deck, allowing helicopters of various sizes—from light (Westland Super Lynx Mk.95A) to medium-lift (NHIndustries NH90) and heavyweight (AgustaWestland AW101 Merlin)—to operate. The hangar can house two mid-sized rotorcrafts, and the cargo deck will have a maximum capacity of 18 TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units), which can be adapted to carry 18 light utility vehicles or 10 RHIBs (Rigid Hull Inflatable Boats). The flexible cargo deck enhances the ship’s versatility, enabling it to perform a wide range of missions, including search and rescue (SAR), humanitarian assistance, and oceanographic research. Containerized modular systems could include hyperbaric chambers, medical facilities, refrigerated storage, scientific labs, and ROV (Remotely Operated Vehicle) equipment.

On the other hand, the ship will feature more advanced elements. The NRP Dom João II will include at least one catapult on the flight deck’s starboard bow to launch light UAVs. Additionally, the ship’s 94-meter runway can support larger drones. The Portuguese Navy currently operates UAVision’s Ogassa OGS42 UAVs in the VTOL (vertical take-off and landing) configuration,[6] but the new MPSS will also have the capability to deploy them in the STOL (short take-off and landing) mode. The ship will also include a stern ramp for deploying and recovering unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) and unmanned surface vehicles (USVs). For example, the Portuguese Navy uses the SEACON-3 UUS. Developed by the Laboratório de Sistemas e Tecnologia Subaquática (LSTS), a Porto-based interdisciplinary research hub on unmanned technologies, the SEACON-3 is a flexible asset for SAR, mine warfare, and ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance) missions.[7]

Figure 2: NRP Dom João II – mother ship for unmanned systems

Source: Revista de Armada, https://www.marinha.pt/conteudos_externos/Revista_Armada/PDF/2024/RA_592.pdf.

With its rich naval tradition, Portugal faces significant challenges, including a vast maritime territory to safeguard, rapidly evolving threats, a structural shortage of trained manpower, and budget constraints. To address these challenges, Lisbon has embarked on a naval modernization program that incorporates unmanned systems as force multipliers. This approach is aimed at bolstering the Navy’s capacity to respond to both conventional and asymmetric threats.

The establishment of the Unmanned Vehicles Operational Experimentation Cell (Célula de Experimentação Operacional de Veículos Não Tripulados, CEOV) in October 2017 marked a turning point for the Portuguese Navy’s quest in the automation sector. This initiative accelerated the development and experimentation with unmanned technologies in maritime operations. Since then, the Portuguese Navy has tested several USV prototypes for a wide range of tasks, from scientific research to patrolling, surveillance, and combat operations. The Navy trialed the CEOV’s X-2601 catamaran for hydrographic research in 2020.[8] Since 2022, the Navy has also conducted operational experimentation with the X-2701 and X-2801 USVs, which are high-speed, multi-mission armed autonomous vessels.[9] Additionally, the Unmanned Oceanic Patrol Vehicle (UOPV), developed by Portuguese firms TecnoVeritas and Nautiber Shipyard, was tested in 2023.[10] Finally, in October 2024, the Portuguese Navy tested a prototype for an offshore artificial platform to serve as a forward base for supporting diving operations, oceanographic research, ship traffic monitoring, and uncrewed systems.[11]

Figure 3: Portuguese Navy’s UAVision OGASSA OGS42

Source: UAVision, https://www.uavision.com/ogassa-ogs42.

In February 2024, the Portuguese Navy created the X31 Unit, a squadron-like unit responsible for coordinating the integration of unmanned systems across the armed forces. This unit is tasked with developing a multidomain drone warfare doctrine, enhancing manned-unmanned cooperation, and conducting rigorous training exercises to ensure operational readiness.[12] The X31 Unit reflects Portugal’s growing focus on autonomous technologies, which have become a key element of its defense planning and strategic thinking.

Lisbon’s strides in integrating autonomous systems into its naval forces are not isolated efforts but part of a broader plan to modernize the country’s naval inventory.[13] In addition to the NRP Dom João II, Portugal has placed orders for six Viana do Castelo-class offshore patrol vessels (OPVs) from the Portuguese West Sea–Estaleiros Navais and two multirole logistics support ships from the Turkish shipbuilder STM.[14]

Despite challenges, such as staffing shortages and the limited number of surface combatants, Portugal significantly contributes to the defense architecture of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Strategically located at the western edge of continental Europe, Portugal serves as NATO’s sentinel in the eastern Atlantic. Besides, the Azores archipelago provides key military facilities for monitoring maritime routes crossing the Atlantic. As Russian naval activity increases in the region, the Portuguese Navy has seen an unprecedented number of Russian warship transits off Europe’s southwestern coast in 2024.[15] This has highlighted the need for Lisbon to have a more active involvement in NATO’s monitoring infrastructure.

However, ramping Russian naval activity levels, combined with the scarcity of surface vessels and elevated costs of protracted simultaneous deployments, put the Portuguese Navy’s surveillance and data collection capabilities to the test. To address these challenges, Portugal is turning to autonomous systems. Unmanned solutions offer significant advantages, including extended deployment times and reduced operational costs, making them invaluable in surveillance and data collection. Autonomous systems also minimize personnel risks, an important consideration given the high operational tempo of observation missions and the scarcity of surface vessels.

In conclusion, the NRP Dom João II is more than just a naval asset. It is expected to be the cornerstone of Portugal’s drone doctrine, representing Portugal’s commitment to modernizing its naval forces and embracing autonomous technologies to address evolving security challenges. By incorporating unmanned systems into its daily naval operations, Portugal is positioning itself as a key player in NATO’s defense efforts, particularly in the increasingly strategic Atlantic region. The ship’s advanced capabilities underscore Portugal’s determination to maintain a strong, versatile, and technologically advanced naval presence on the global stage.

Second Case: Iran

Iran has also joined the small group of nations worldwide exploring the concept of drone carriers—ships specifically designed or retrofitted to UAVs as part of maritime warfare. Among these, the Islamic Republic has taken a distinct approach, leveraging commercial vessel conversions to enhance its asymmetric warfare doctrine. On 6 February 2025, Iran commissioned the Islamic Republic of Iran Ship (IRIS) Shahid Bahman Bagheri (C110-4) into the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Navy in a ceremony held in Bandar Abbas, on the Strait of Hormuz.[16] Senior Iranian military officials, including General Hossein Salami, Major General Mohammad Bagheri, and the Minister of Defense, attended the event. The commissioning marked a significant milestone in Iran’s naval modernization, introducing its first and only dedicated drone carrier into service.

Figure 4: IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri

Source: Fars News Agency (FN), https://farsnews.ir/Sayeh/1738821811134984162/Iran%E2%80%99s-Drone-Carrier-Warship-Joins-IRGC-Navy-in-Gulf.

Originally built as the South Korean-made container ship Perarin (IMO 9209350) in 2000,[17] the IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri was converted into a drone carrier through an extensive retrofitting process carried out by the Iran Shipbuilding & Offshore Industries Complex Co. (ISOICO) between 2022 and 2024. Named after IRGC commander Shahid (“martyr”) Bahman Bagheri, who died during the Iran-Iraq War, sea trials began in November 2024, with final modifications to the vessel’s aviation facilities completed in early 2025.[18]

Given Iran’s economic constraints and international embargoes, the country has a history of converting commercial vessels for military use. Examples include the IRIS Makran forward base ship and the IRIS Shahid Roudaki and IRIS Shahid Mahdavi warships.[19] However, unlike the latter two—which serve as launch platforms for UAVs and helicopters but lack a dedicated airstrip for UAV recovery—the IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri is specifically configured as a drone carrier.

Information regarding the ship’s capabilities is limited to open-source intelligence and Iranian state media reports, which are often exaggerated for strategic messaging. The vessel retains elements of its original commercial structure while integrating military upgrades, including a 180-meter angled flight deck with a ski jump similar to those on light aircraft carriers. The ship measures 240.2 meters in length, has an estimated displacement of approximately 42,000 tons, and is powered by a MAN B&W Type 8 S70 MC-C diesel engine, providing a top speed exceeding 20 knots.[20]

Figure 5: IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri’s angled deck

Source: Tasnim News Agency (TNA), https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1403/11/18/3252524.

Iranian sources claim that the carrier can deploy up to 60 UAVs alongside helicopters and air defense systems,[21] though independent verification is lacking. Footage from its commissioning ceremony confirmed the presence of Mohajer-6 and Ababil-3N UAVs on its flight deck. The Qods Mohajer-6 is a mid-range ISTAR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Target Acquisition, and Reconnaissance) combat UAV with a claimed operational range of 200 km and a payload capacity of 150 kg, capable of carrying guided missiles or bombs.[22] Meanwhile, the HESA Ababil-3N is the most common version within the Iranian ranks of the Ababil UAV family, designed for ISR and strike missions.[23]

The IRGC Navy also showcased prototype drones of unknown capabilities.[24] One, the Homa, is a vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) UAV, though its operational status remains unclear.[25] Another drone, designated JAS-313, visually resembles the Qaher-313 fighter jet, which Iran first unveiled in 2013 but never entered service. These UAVs, with a stated flight endurance of an hour, were displayed in two scaled variants—20% and 60% of the original Qaher-313.[26] Footage from the ceremony shows a JAS-313 UAV—reportedly powered by a Jahesh–700 turbofan engine— successfully launched from the carrier’s ski-jump and conducted a brief flight over the ship.[27] However, it remains unclear which operational naval UAV platform they represent or whether any are combat-ready. The deck also supports American-designed Bell Model 206 and 212 helicopters and Russian Mi-17 Hips.

Figure 6: JAS-313 UAVs on the IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri’s deck

Source: Tasnim News Agency (TNA), https://www.tasnimnews.com/en/news/2025/03/03/3268599/unmanned-jets-aboard-irgc-navy-s-drone-carrier-fit-for-combat.

Beyond its aviation-related capabilities, the IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri appears capable of launching and recovering up to 30 missile boats and fast-attack craft via davits on either side of its hull. This includes Taregh-class Fast Attack Craft (FAC), each armed with four Kowsar missiles, with a top speed of 46 knots and a range of 500 nautical miles, as well as Zolfaqar, Ashura, Heidar, and Miyad-class vessels—given the IRGC Navy’s extensive fleet of speedboats.[28] Unconfirmed reports suggest it may also deploy uncrewed surface and underwater vehicles (USVs and UUVs), reinforcing Iran’s asymmetric naval doctrine.[29]

The vessel has its own onboard armament, reportedly equipped with a mix of short- and medium-range air defense systems and anti-naval capability. This includes eight C-802A (Ghader) cruise anti-ship missiles launchers at the aft end, eight Kowsar-222 multi-purpose air defense missiles,[30] a 30mm automatic cannon in a turret at the bow and four 20mm Gatling-type cannons, potentially in remote-controlled turrets. Iranian officials also claim the vessel is equipped with electronic warfare (ESM) and intelligence-gathering (SIGINT) systems, though no clear evidence has emerged to verify these capabilities.[31]

Iran’s investment in the IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri drone carrier reflects the evolving nature of its long-standing asymmetric warfare doctrine. Historically, Tehran has relied on a mix of speedboats, mines, anti-ship missiles, and submarines patrolling the Gulf, often threatening to close the Strait of Hormuz. This has allowed Iran to offset its conventional naval disadvantages with Western and regional adversaries.

Iran’s investment in the IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri reflects the evolving nature of its maritime strategy, which traditionally relied on asymmetric warfare.[32] Historically, Iran has used speedboats, mines, anti-ship missiles, and submarines to counterbalance its conventional naval disadvantages. However, in recent years, the Islamic Republic has strengthened its conventional naval forces, acquiring advanced warships[33] and submarines while expanding its presence in international waters as far as the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

These developments align with Iran’s “forward defense” doctrine, which prioritizes power projection beyond its borders to deter adversaries before they pose a direct threat.[34] The addition of a drone carrier enables Iran to expand its UAV capabilities into the maritime domain, enhancing its ability to conduct long-range ISR and strike missions in strategic waterways. As such, the vessel’s immediate role will focus on improving Iran’s brown-water capabilities—securing chokepoints like the Strait of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandeb.

Still, its design indicates ambitions for blue-water operations. IRGC Navy Commander Rear Admiral Ali Reza Tangsiri claims the drone carrier has a 22,000-mile operational range and can operate in Sea State 9, enabling sustained missions without refueling for up to a year. Thus, the ship was developed to extend Iran’s defense capabilities beyond its borders, providing Iran with a mobile base for operations in distant waters like the Gulf of Oman, the Arabian Sea, the Indian Ocean, and perhaps farther. Iranian officials further assert that the vessel will secure Iranian shipping lanes while reducing reliance on foreign naval forces.[35] The presence of a medical bay, a gymnasium with an astroturf soccer pitch, and basketball hoops further underscores that the ship was designed for extended deployments far from Iranian waters. While Iran’s Navy continues to focus on asymmetric tactics, the IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri highlights its aspirations for blue-water capabilities and global power projection.

Iran’s expansion into naval drone warfare also presents new challenges for regional actors, particularly the United States, Israel, and Gulf states like Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Persistent UAV surveillance and potential swarm attacks raise security risks in key shipping lanes. Additionally, the ship’s mobility allows Iran to project power beyond its traditional areas of operation, requiring Western and regional navies to reassess their maritime security strategies. Iran’s naval strategy also involves closer cooperation with China and Russia. Since 2019, Iran has conducted multiple joint naval exercises with both countries, reflecting a broader approach to counterbalance Western maritime dominance. The Defense Industries Organization (DIO) has also sought Russian expertise to enhance Iran’s long-range naval precision missiles.[36]

Despite its strategic ambitions, Iran faces several challenges in fully operationalizing its drone carrier fleet. The IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri and similar vessels have inherent limitations that may restrict their effectiveness in high-intensity conflict scenarios. One major challenge is the vulnerability of these drone carriers to advanced naval forces. Unlike aircraft carriers or large amphibious assault ships, Iran’s converted vessels lack significant defensive systems. Without adequate air defense, these ships could be highly susceptible to preemptive strikes from adversaries using precision-guided munitions or electronic warfare (EW) capabilities.

Furthermore, the IRGC Navy lacks capable escort vessels to protect the IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri against air and underwater threats. Iran’s Second Fleet, responsible for maritime operations within and beyond the Strait of Hormuz, operates only a limited number of outdated light frigates and corvettes, which lack advanced air defense and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capabilities and would be insufficient to safeguard the carrier in high-risk environments. Without significant improvements in naval escorts, Iran’s ability to operate a drone carrier beyond the Gulf remains constrained. Additionally, Iran’s drone carrier’s effectiveness depends on its ability to coordinate complex UAV operations in contested environments. While Iranian drones have proven effective in asymmetric scenarios, their resilience against modern counter-UAV measures, such as laser-based air defenses and advanced electronic jamming, remains questionable. If adversaries deploy more sophisticated UAV countermeasures, Iran’s drone carriers may struggle to maintain their offensive advantage.

Logistical constraints also pose a challenge. Iran’s Navy has historically struggled to maintain and sustain long-range naval operations. Unlike conventional warships with extensive resupply networks, Iran’s drone carriers rely on a more limited support infrastructure, potentially restricting their operational range and endurance.

Nevertheless, the introduction of drone carriers marks a significant step in Iran’s naval modernization, signaling its intent to leverage UAV technology as a force multiplier at sea. The IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri represents the next step in Iran’s evolution as a drone warfare power, signaling Tehran’s commitment to expanding its influence through innovative naval solutions. However, the effectiveness of this new capability will largely depend on Iran’s ability to refine UAV operations in contested maritime environments and overcome operational and logistical constraints.

Third Case: Türkiye

Türkiye developed a homegrown drone industry in the 2010s due to political obstacles in acquiring the U.S.-made Predator drones and technical hurdles in operating Israeli Herons. With the government’s strategic directive to invest in R&D and local arms production, this push for domestically produced drones has resulted in the development of multiple high-standard systems, showcasing advanced capabilities and innovation—with the Baykar Bayraktar TB-2 standing out as a notable success in the global market. With a superior cost-effectiveness ratio and proven battlefield success, Turkish drones have garnered significant attention, particularly from conflict-prone emerging countries in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. With NATO compatibility and cross-domain warfare expertise, Türkiye provides not only UAVs but also a complete doctrine in AI-assisted 5th-generation multidomain warfare. Today, Türkiye holds 65% of the global drone market, mostly through products launched by Baykar and the Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI).[37]

Figure 7: TCG Anadolu LHD

Source: Anatolia News Agency (AA), Türkiye Today, https://www.turkiyetoday.com/region/turkiyes-blue-homeland-2025-naval-drill-sparks-concern-from-greek-media-101282/.

Unlike Portugal and Iran, however, Türkiye’s expansion of drone capabilities into the naval domain was initially unintentional. Its first landing helicopter dock/amphibious assault ship (LHD), TCG Anadolu (L-400), was planned to carry 20 F-35B STOVL fighter jets (the carrier variant of F-35A), a product of the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) consortium that Türkiye had been part of since 2007. However, after Ankara was expelled from the F-35 program in 2019 due to its purchase of Russian S-400 missile systems and subsequent CAATSA sanctions, the Turkish defense industry pivoted toward an indigenous naval drone doctrine, transforming Anadolu into the world’s first dedicated UAV carrier.

Engineers then modified the TCG Anadolu’s original design in 2020 to fit it with foldable-wing Bayraktar TB-3—the sea variant of TB-2—and potentially other UCAVs such as Baykar Kızılelma and TAI Anka-3. Major additions included drone control stations with satellite terminals for longer-range connections, a “roller system” at the ship’s bow to help launch uncrewed aircraft, an arresting gear system on deck to make UCAV landings easier, and safety nets to recover smaller drone types.[38] Powered by the Turkish Engine Industry (TEI)’s indigenous PD-170 engine, TB-3 made its first successful test flight aboard TCG Anadolu on 19 November 2024.[39] The drone is expected to enter service in 2025 and soon become part of manned-unmanned teaming arrangements with other aerial units in Türkiye’s arsenal.

Figure 8: TB-3 takes off from TCG Anadolu

Source: Baykartech, https://baykartech.com/en/press/bayraktar-tb3-uav-successfully-continues-ship-tests/.

Initially, TCG Anadolu will carry up to 50 TB-3s UCAVs plus 10 Super Cobra helicopters. The ship is built by Sedef Shipyard in Türkiye, based on Navantia’s design for Spain’s flagship, Juan Carlos I (L-61), through the transfer of know-how and technical assistance. Measuring 232m in length and 32m in width, it has a displacement of 27,436 tons, making it the largest vessel in the Turkish Navy. With a range of 9,000 miles at 16 knots, Anadolu is designed to transport a battalion-sized amphibious force including a Zaha armored combat vehicle and the soon-to-come Altay battle tank for the marines. Anadolu is equipped with Havelsan ADVENT Combat Management System along with an array of electronic warfare systems, comprehensive communication and tactical data link capabilities, torpedo countermeasures, and a diverse weapons suite including remote-controlled naval guns, close-in weapon systems (CIWS), and a Mk49 Mod 3 RAM missile launcher for robust air and surface defense.[40] It features elevators to transfer NATO-compatible large aerial platforms like S-70 SeaHawk and CH-47 Chinook from the hangar to the flight deck, and a ski-jump with a 12-degree incline on the bow suitable for short take-offs. Türkiye stands out as one of the few operators of unmanned drones on naval carriers, which are also increasingly becoming more popular among Asian navies. Considered as a cheap, efficient option compared to large aircraft carriers, which are vulnerable to hypersonic missiles, naval drones “enable more advanced operations that do not necessarily endanger the pilot or the operator, whether it is a mission of reconnaissance, intelligence or combat.”[41]

With a 75% local input rate, TCG Anadolu is a landmark platform that demonstrates synergies between different branches of the military-industrial complex. The ruling government under President Erdoğan rolled out a techno-economic nationalization program called Yerli ve Milli (local and national) pioneered by the defense industry and starred by his son-in-law Selçuk Bayraktar, chief innovator of Baykar UAVs, “stressing the need for domestic production of goods for strategic reasons.”[42] TCG Anadolu broadens the Turkish defense industry’s horizon and showcases how a middle-sized power like Türkiye can now project force abroad and shape the narrative in easy, straightforward, and cost-effective ways.

TCG Anadolu also marks an essential cornerstone in Türkiye’s quest to claim its place as an emerging maritime power. Türkiye operationalizes a fleet of more than one hundred naval vessels at sea to meet a key criterion for having a formidable maritime force. The next step is to project power beyond Anti-Access/Area-Denial (A2/AD) bubbles in coastal waters, which kick-starts with deployments overseas. In recent years, Türkiye asserted its maritime rights through the “Blue Homeland” concept, often via gunboat diplomacy around Cyprus and the nearby Greek islands. Türkiye’s broader strategy encompasses having a permanent overseas presence in Cyprus, military basing rights in Libya and Qatar, as well as operations in Somalia, all designed to counter perceived encirclement by rivals along its vulnerable frontiers, from Iraq to the Aegean Sea. The Blue Homeland doctrine functions as a coercive diplomatic instrument in theaters of potential conflict while recent naval exercises with the same title highlight its tactical significance within a wider strategic contest across these regions. From this perspective, TCG Anadolu constitutes the backbone of Türkiye’s power projection capabilities for the next decade.

More broadly, the Turkish Navy’s biggest strength is indigenous capabilities to build platforms and modern weapon systems. Twenty years ago, it was largely dependent on U.S./NATO-supplied equipment; today, local components make up about 75-80% of inputs, ranging from Istanbul-class frigates to Ada-class corvettes, from ATMACA anti-ship missiles to the Advent combat management system. TCG Anadolu also paved the way for the Turkish Navy to consider building a homegrown aircraft carrier. In February, the navy announced steel-cutting ceremonies for the MUGEM aircraft carrier (60,000 tons), TF-2000 anti-air warfare (AAW) destroyer, and MİLDEN submarine. If the goal is to establish a complete power-projection force, it should consist of a carrier strike group centered on the MUGEM carrier, two amphibious task groups led by TCG Anadolu and the future TCG Trakya, and TF-2000-class AAW destroyers for air coverage. This structure would enable operations across the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and the western Indian Ocean.

Türkiye’s rapid naval advancements, driven by local production and drone integration, signal its ambition to transition from a regional power to a true blue-water navy. The development of TCG Anadolu underscores a strategic shift toward power projection beyond its immediate waters. However, sustaining this momentum will require balancing technological innovation with economic feasibility and managing regional tensions, particularly with Greece and NATO allies. As automation and unmanned systems redefine modern naval warfare, Türkiye’s evolving maritime doctrine will play a crucial role in shaping the geopolitical landscape of the Mediterranean and beyond.

Conclusion

The increasing adoption of drone carriers by small and mid-powers reflects a broader shift in naval strategy, where unmanned systems are reshaping power projection. Portugal’s NRP Dom João II represents a technologically advanced platform designed to integrate UAVs into daily fleet operations, mitigating manpower constraints and enhancing NATO’s surveillance capabilities. Iran’s IRIS Shahid Bahman Bagheri exemplifies an asymmetric approach, leveraging commercial vessel conversions to expand its maritime UAV operations and project power beyond its borders. Meanwhile, Türkiye’s TCG Anadolu highlights the nation’s rapid strides in indigenous drone development, transforming its naval doctrine toward greater force projection and regional influence.

Each of these nations is utilizing drone carriers to expand its maritime presence and strategic reach, albeit through different operational and technological approaches. As unmanned systems become a central component of naval warfare, drone carriers will play a critical role in shaping future maritime security dynamics, enabling smaller and medium-sized powers to extend their operational reach at a lower cost than traditional aircraft carriers. This shift not only expands access to sea-based air power but also introduces new security challenges, compelling naval forces to adapt to an era in which unmanned systems are poised to play a decisive role in maritime strategy.

[1] “Intervenção do CEMA e AMN – Cerimónia da Assinatura do contrato de construção da Plataforma Naval Multifuncional do PRR,” Revista de Armada, n. 592, Ano LIV, February 2024, pp. 14-15, https://www.marinha.pt/conteudos_externos/Revista_Armada/PDF/2024/RA_592.pdf.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Damen holds joint steel cutting and keel laying ceremony for Portuguese Navy’s Multi-Purpose Ship,” Damen, October 3, 2024, https://www.damen.com/insights-center/news/damen-holds-joint-ceremony-for-portuguese-navy-s-multi-purpose-ship.

[4] “Intervenção do CEMA e AMN – Cerimónia da Assinatura do contrato de construção da Plataforma Naval Multifuncional do PRR,” Revista de Armada, op. cit.

[5] Ibid; “Multi-Purpose Support Ships,” Damen, https://www.damen.com/vessels/defence-and-security/multi-purpose-support-ships.

[6] “OGASSA OGS4,” UAVision, https://www.uavision.com/ogassa-ogs42.

[7] “Revamp of LAUV-SEACON-3,” Laboratório de Sistemas e Tecnologia Subaquática, May 20, 2022, https://lsts.fe.up.pt/news/revamp-lauv-seacon-3.

[8] “Inovação: Marinha desenvolve sistema marítimo autónomo para apoiar investigação científica,” Marinha, May 18, 2020, https://www.marinha.pt/pt/media-center/Noticias/Paginas/Inovacao-Marinha-desenvolve-sistema-maritimo-autonomo-para-apoiar-investigacao-cientifica-.aspx.

[9] Victor Barreira, “Portugal develops armed USV,” Janes, July 4, 2022, https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-news/defence/portugal-develops-armed-usv.

[10] “UOPV,” Tecnoveritas, https://www.tecnoveritas.net/rd-projects/uopv/; Rolando Santos, “UOPV: o drone naval português que vai ser testado pela Marinha,” CNN Portugal, March 17, 2023, https://cnnportugal.iol.pt/videos/uopv-o-drone-naval-portugues-que-vai-ser-testado-pela-marinha/6414be4a0cf2c84d7fcd01d8.

[11] Lee Willett, “REPMUS 24: Portuguese Navy Tests Autonomous ‘Island’ to Support Maritime Uncrewed System Operations,” Naval News, October 3, 2024, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/10/repmus-24-portuguese-navy-tests-autonomous-island-to-support-maritime-uncrewed-system-operations/.

[12] “Marinha faz História com a criação de uma nova unidade!,” Marinha, February 9, 2024, https://www.marinha.pt/pt/media-center/Noticias/Paginas/Marinha-faz-Historia-com-a-criacao-de-uma-nova-unidade.aspx.

[13] Victor M.S. Barreira, “Portugal’s comprehensive equipment modernisation,” European Security and Defence, March 14, 2024, https://euro-sd.com/2024/03/articles/37091/portugals-comprehensive-equipment-modernisation/.

[14] Victor Barreira, “Portugal orders six modified Viana do Castelo-class OPVs,” Janes, January 3, 2024, https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-news/sea/portugal-orders-six-modified-viana-do-castelo-class-opvs; Tayfun Ozberk, “Portuguese Navy Awards Türkiye’s STM Contract to Build Multirole Logistics Support Ships,” Naval News, December 17, 2024, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/12/portuguese-navy-awards-turkiyes-stm-contract-to-build-multirole-logistics-support-ships/.

[15] “Portugal’s Small Navy Tracks Rising Level of Russian Activity in Atlantic,” The Marine Executive, November 26, 2024, https://maritime-executive.com/article/portugal-s-small-navy-tracks-rising-level-of-russian-activity-in-atlantic#:~:text=Portugal’s%20Small%20Navy%20Tracks%20Rising%20Level%20of%20Russian%20Activity%20in%20Atlantic,-The%20Russian%20spy&text=Portugal’s%20military%20is%20warning%20of,require%20diligent%20monitoring%20and%20tracking.

[16] “Unique Features of the “Shahid Bagheri Drone Carrier,”” Tasnim News, February 18, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1403/11/18/3252456.

[17] PERARIN, Container Ship (IMO: 9209350), Marinetraffic, March 13, 2021, https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/details/ships/shipid:657729/mmsi:422026800/imo:9209350/vessel:PERARIN

[18] Boaz Shapira, “Iran unveils its first drone ship, the “Shahid Behman Bagheri,” Aurora, February 9, 2025, https://aurora-israel.co.il/en/Iran-unveils-its-first-drone-ship-Shahid-Behman-Bagheri/

[19] Yusuf Çetiner, “The IRGC Navy Adds 95 Speedboats and the Shahid Mahdavi Warship To Its Fleet,” Overt Defense, March 14, 2023, https://www.overtdefense.com/2023/03/14/the-irgc-navy-adds-95-speedboats-and-the-shahid-mahdavi-warship-to-its-fleet/

[20] Joseph Trevithick, “Iran’s Wacky Aircraft Carrier Has Entered Service,” The War Zone, February 6, 2025, https://www.twz.com/sea/irans-wacky-aircraft-carrier-has-entered-service#:~:text=The%20new%20pictures%20and%20videos,Revolutionary%20Guard%20Corps%20(IRGC)

[21] “Shahid Bagheri drone carrier joins IRGC Navy,” IRNA, February 18, 2025, https://www.irna.ir/news/85742064

[22] Francesco Salesio Schiavi, “Assessing Russian Use of Iranian Drones in Ukraine: Facts and Implications,” ISPI, October 26, 2022, https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/assessing-russian-use-iranian-drones-ukraine-facts-and-implications-36520.

[23] “Ababil-3 Iranian Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV),” ODIN TCT, https://odin.tradoc.army.mil/WEG/Asset/38ce4c2315f24f7be37704d9cd1603cc.

[24] “The shadow of IRGC drones over the oceans with the Shahid Bagheri ship,” TNA, February 18, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1403/11/18/3252524.

[25] “Homa & Chamrosh-4 VTOL UAVs,” Iran Defense, Twitter, December 2, 2023, https://x.com/IranDefense/status/1731061137754443919.

[26] “Unmanned Jets Aboard IRGC Navy’s Drone Carrier Fit for Combat,” TNA, March 3, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/en/news/2025/03/03/3268599/unmanned-jets-aboard-irgc-navy-s-drone-carrier-fit-for-combat.

[27] Tayfun Ozberk, “Iran accepts delivery of homegrown drone carrier Shahid Bahman Bagheri,” NavalNews, February 6, 2025, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2025/02/iran-accepts-delivery-of-homegrown-drone-carrier-shahid-bahman-bagheri/.

[28] “The Military Balance 2024,” IISS, Routledge, February 2024, pp.354-55.

[29] “Salami: We have built the drone carrier for long-distance defense,” TNA, February 18, 2024, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1403/11/18/3252459.

[30] “Iran debuts Kowsar 222 Missile in Gulf Naval Drills: Advanced Air Defense in Action,” Army Recognition, January 28, 2025, https://tinyurl.com/2enzkwrt.

[31] “IRGC Navy’s Drone Carrier A Mobile Maritime Platform for Drone, Helicopter Missions,” TNA, February 6, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/en/news/2025/02/06/3252659.

[32] Farzin Nadimi, “Iran’s Evolving Approach to Asymmetric Naval Warfare: Strategy and Capabilities in the Gulf,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, April 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20200504225030/https:/www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/pubs/PolicyFocus164-Nadimi-v2.pdf.

[33] “Two new warships added to IRGC Navy Force,” Tehran Times, February 19, 2024, https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/495138/Two-new-warships-added-to-IRGC-Navy-Force.

[34] Hamidreza Azizi, “Iran’s New Naval Ambitions,” Foreign Affairs, July 10, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/iran/irans-new-naval-ambitions.

[35] “Salami: We have built the drone carrier for long-distance defense,” TNA, February 18, 2024, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1403/11/18/3252459.

[36] “Iran’s Long Range Missile Capabilities,” The Iran Watch, https://www.iranwatch.org/library/government/united-states/congress/legislation-reports/irans-long-range-missile-capabilities.

[37] Pramod Kumar, “Turkey Holds 65% of Global Drones Market,” AGBI, December 16, 2024, https://www.agbi.com/manufacturing/2024/12/turkey-holds-65-of-global-drones-market/.

[38] Sakshi Tiwari, “Bayraktar Drone ‘Replaces’ F-35 For TCG Anadolu Ops! Turkey Operates TB3 UCAV From Amphibious Warship,” EURASIAN TIMES, November 21, 2024, https://www.eurasiantimes.com/turkish-revenge-for-f-35-humiliation/.

[39] “Bayraktar TB3, TCG Anadolu’ya Ilk Kalkış ve Inişini Başarıyla Tamamladı,” AA, November 19, 2024, https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/gundem/bayraktar-tb3-tcg-anadoluya-ilk-kalkis-ve-inisini-basariyla-tamamladi/3398031.

[40] İbrahim Sünnetçi, “TCG ANADOLU Multi-Purpose Amphibious Assault Ship Planned to Be Delivered at the End of 2022,” Defense Turkey, September 17, 2022, https://www.defenceturkey.com/en/content/tcg-anadolu-multi-purpose-amphibious-assault-ship-planned-to-be-delivered-at-the-end-of-2022-5238.

[41] Tavşan Sinan, “Asian Navies Adopt Drone Warfare as Cheap, Efficient Option,” Nikkei Asia, March 2, 2025, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Aerospace-Defense-Industries/Asian-navies-adopt-drone-warfare-as-cheap-efficient-option.

[42] Norrin M. Ripsman, Jeffrey W. Taliaferro, and Steven E. Lobell, Neoclassical Realist Theory of International Politics, Neoclassical Realist Theory of International Politics (Oxford University Press, 2016), 154, https://oxford-universitypressscholarship-com.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199899234.001.0001/acprof-9780199899234.