1. Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa has grown into a region of increasing significance in the global economic landscape, and its relationship with international organizations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been crucial in shaping its development trajectory. Despite a wealth of resources and a young, dynamic population, Sub-Saharan Africa faces unique economic challenges. How have the IMF and the World Bank influenced the development of key African economies, and what role do these institutions play in navigating the regional economic stability?[1]

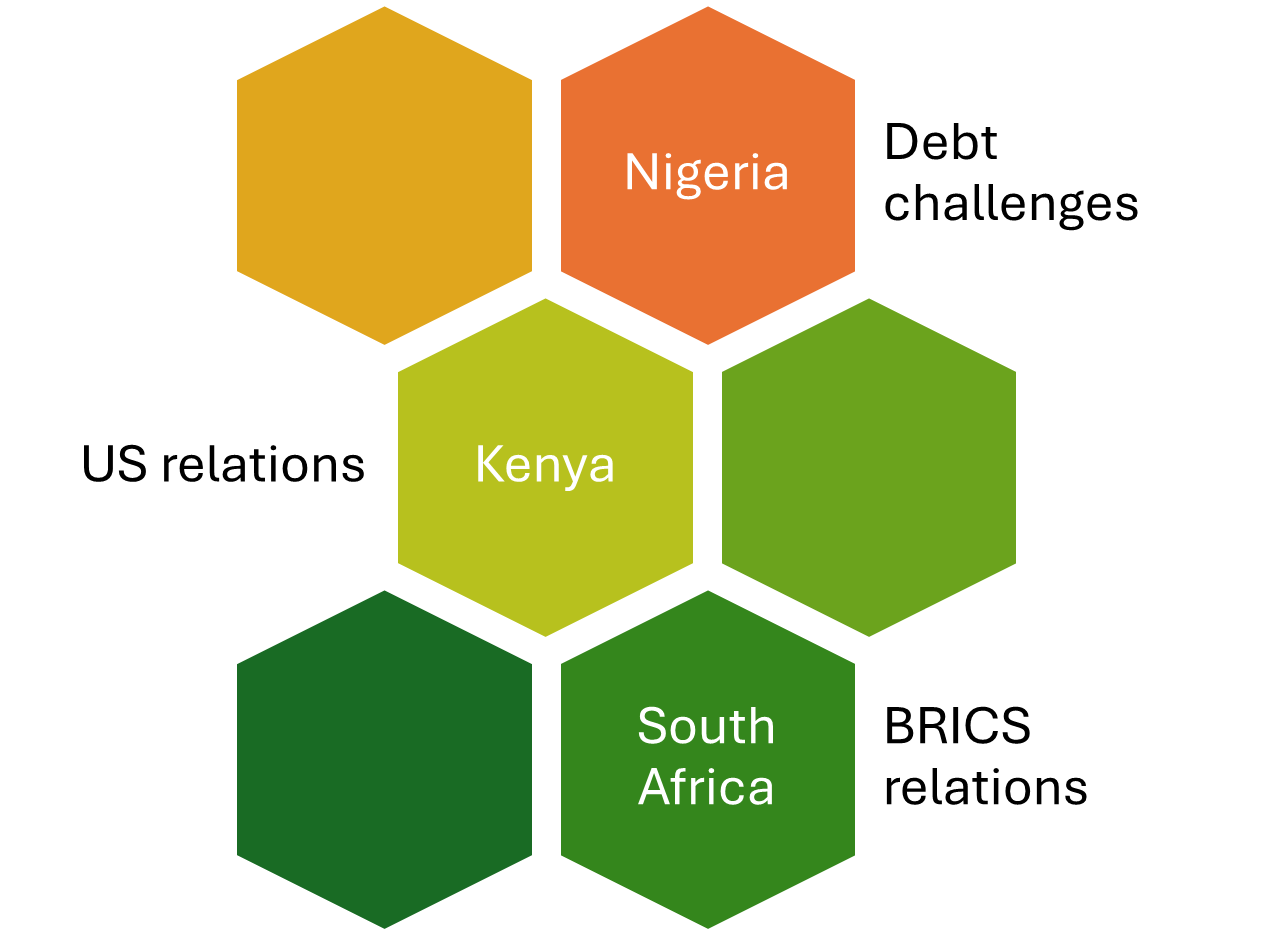

This paper examines the relationships between Sub-Saharan Africa and the Bretton Woods institutions, focusing specifically on Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa. These countries’ interactions with the IMF and the World Bank illustrate the varying influence of these institutions on the region’s economic strategies. Nigeria, with its resource-rich economy, faces complex debt and development challenges. Kenya, positioned as an East African economic hub, aligns with U.S.-backed policies in pursuit of growth. Meanwhile, South Africa, the continent’s most industrialized nation and a BRICS member, represents an alternative approach by balancing traditional IMF/World Bank relations with emerging economic partnerships. Each case study illustrates the broader implications of Bretton Woods engagement for Sub-Saharan Africa.[2]

This analysis is based on historical data, economic reports, and direct insights from the World Bank and IMF. By examining economic policies, development programs, and growth metrics influenced by Bretton Woods institutions, the paper provides a detailed evaluation of these relationships. Quantitative data, including recent reports from the IMF and World Bank, support the analysis of each case study.[3]

2. Theoretical Framework

Clarifying key terms and organizations relevant to this paper is essential for enhancing the reader’s understanding throughout. Therefore, this section addresses three foundational aspects: a brief history of the Bretton Woods institutions and their inception, an overview of the economic context in the Sub-Saharan region, and an exploration of the link between the two. These elements will set the stage for a clearer discussion of the topic in the subsequent sections.

2.1 Brief History of Bretton Woods

The Bretton Woods system was established in July 1944 at the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, held at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, U.S. Forty-four nations gathered to design a new international monetary system aimed at ensuring economic stability and preventing crises like those experienced during the Great Depression and the two world wars.[4] The outcome of the conference was the creation of two major financial institutions: the IMF and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which later became part of the World Bank Group.[5]

The IMF was initially responsible for overseeing a system of fixed exchange rates, where currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar, while the World Bank primarily focused on post-war reconstruction and long-term economic development in struggling nations.[6] Although the fixed exchange rate system eventually collapsed in the 1970s, the IMF and World Bank have endured, adapting to the evolving global financial landscape. Today, these institutions play pivotal roles in providing financial assistance and policy guidance to countries worldwide, particularly to developing economies that seek economic stability and growth,[7] like Sub-Saharan Africa.

2.2 Economic Context of Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa, known for its abundant natural resources and cultural diversity, has long faced economic challenges rooted in colonial legacies, political instability, and widespread poverty. The region comprises many low-income countries that struggle with limited funding, high borrowing costs, and substantial debt-related risks. Despite these obstacles, Sub-Saharan Africa possesses valuable resources, including oil, gas, and minerals, that—if effectively managed—hold the potential to enhance financial stability. In recent years, however, economic difficulties have deepened as many nations struggle to mobilize domestic resources to meet financial obligations. Low-income countries in the region now need over $70 billion annually—about 6 percent of their GDP—for the next four years to manage their finances effectively.[8] This financial strain has led governments to reduce essential public services and redirect funds intended for development toward debt repayment, hindering long-term growth prospects.[9]

Despite these challenges, Sub-Saharan Africa has significant opportunities for development, particularly due to its youthful population and the potential for human capital investment. With a projected population increase of 740 million by 2050, the region could benefit from policies promoting economic diversification, education, and job creation. However, current job creation rates fall short of accommodating the approximately 12 million young people entering the workforce each year.[10] The region’s dependence on external support, particularly from the IMF and World Bank, underscores the need for strategies that strengthen economic resilience, improve governance, and promote sustainable growth.[11]

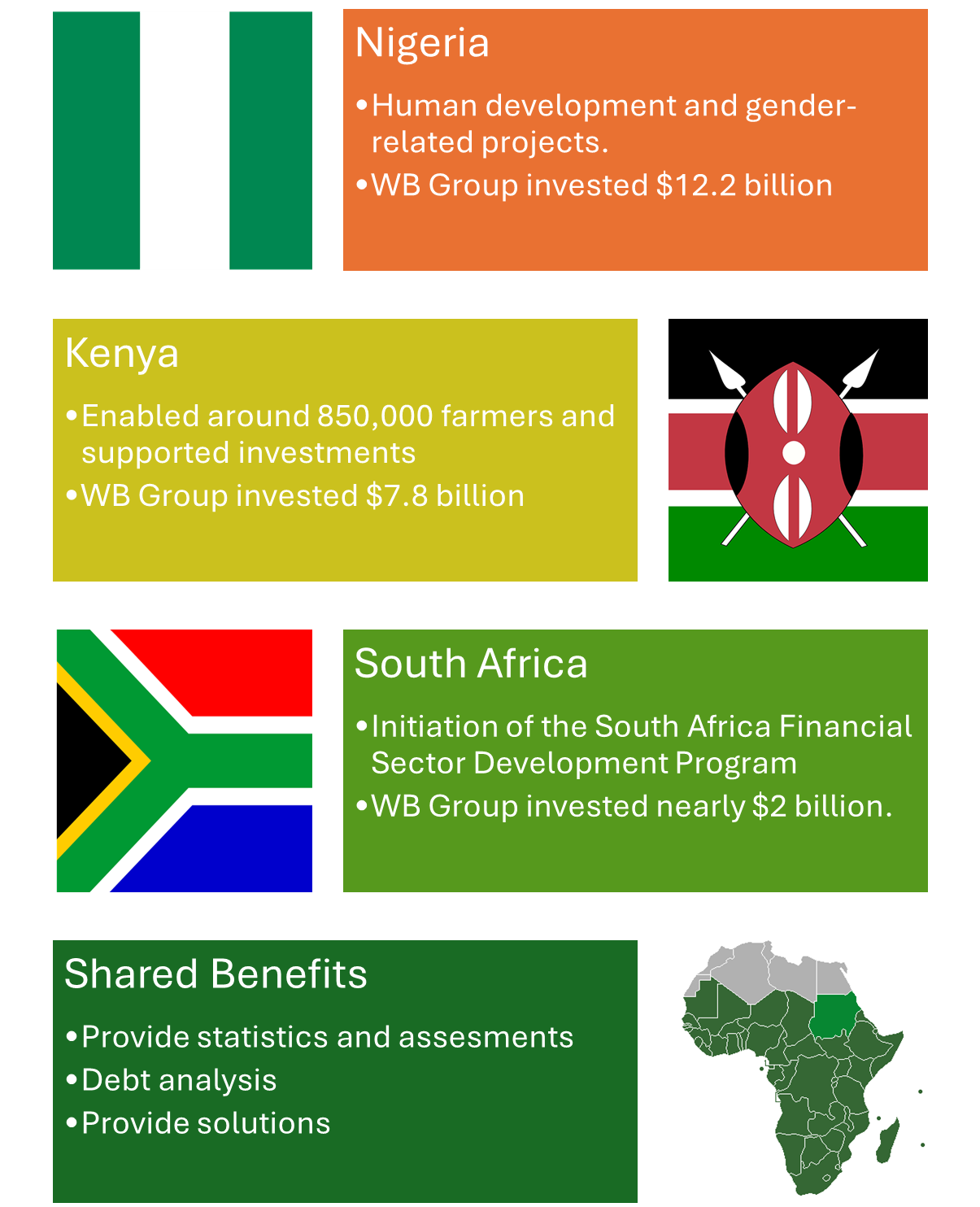

Figure 1: World Bank projects in Sub-Saharan Africa

Source: worldbank.org

2.3 Link Between Bretton Woods and Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa’s engagement with the Bretton Woods institutions has profoundly influenced its economic policies and development paths. Both the IMF and the World Bank play critical roles in shaping the region’s strategies for growth, offering financial resources, policy recommendations, and technical assistance. Each case study—Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa—illustrates a unique aspect of the region’s relationship with these institutions, reflecting various degrees of dependency, alignment, and adaptation. While these institutions aim to promote stability and growth, they have also been criticized for promoting policies that sometimes overlook local needs and exacerbate social inequalities. The Bretton Woods institutions’ influence in Sub-Saharan Africa highlights the complex balance between global financial systems and the autonomy of developing nations in determining their own economic futures.[12] This can be observed particularly with the case studies that this paper focuses on.

Figure 2: Case studies’ challenges

Source: author

3. Case Studies

In the case of Nigeria, the IMF and World Bank have frequently provided financial assistance to manage the country’s high debt levels, often tied to fluctuations in global oil prices. These interventions have been pivotal during periods of economic instability but have also resulted in complex debt-servicing challenges that continue to impact Nigeria’s fiscal policy.

Kenya’s relationship with the Bretton Woods institutions has also been significant, particularly as it navigates its role as a key East African economy. American influence, both through direct aid and policy alignment, has played a central role in Kenya’s economic reforms, particularly in infrastructure development and poverty reduction programs supported by the World Bank. This relationship with the U.S. will be explored as a critical aspect of Kenya’s engagement with the global financial system.

South Africa offers a unique case with its involvement in BRICS, which has complicated its relationship with the Bretton Woods institutions. As South Africa balances its BRICS membership with IMF and World Bank engagement, its economic strategies reflect a dual alignment with both Western and emerging economies, highlighting the complexities of its global economic positioning.

3.1 Nigeria: Managing High Debt

Nigeria, with a population of around 202 million, stands as one of the largest economies in Sub-Saharan Africa and serves as a key case study in exploring the region’s relationship with the Bretton Woods institutions. Known for its vast natural resources, particularly oil, Nigeria’s wealth places it in a unique position among Sub-Saharan African nations. However, despite its economic potential, Nigeria is also one of the continent’s most indebted nations, with public debt reaching $121.67 billion as of March 2024. External debt alone is $36 billion,[13] while nearly 100 million Nigerians live on less than a dollar per day, reflecting inequality in resource distribution.[14]

IMF and World Bank interventions in Nigeria are largely driven by the country’s high debt levels and the volatility of global oil prices, which directly affect the economy.[15] Between 2012 and 2023, Nigeria’s debt increased by 123%, largely due to externally sourced loans that raise concerns over sustainability. Global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict, have further complicated Nigeria’s economic stability, leading to rising inflation and increased poverty rates.[16] The World Bank has been a crucial partner in Nigeria’s development efforts, providing $12.2 billion from 2021 to 2024 to support diverse projects aimed at poverty alleviation, job creation, and social service utilization.[17]

While Bretton Woods interventions aim to stabilize Nigeria’s economy, they often come with conditions that require Nigeria to implement stern fiscal policies. These include the reduction of subsidies and diversification away from oil dependency, which, although beneficial in the long term, have proven politically challenging for Nigeria’s leadership. The World Bank also supports conflict-affected regions, such as North-East Nigeria, where efforts focus on strengthening livelihoods and promoting sustainable development.[18] Statistics show that as Africa’s top oil exporter, Nigeria’s high debt levels have led to substantial IMF interventions, especially when oil price fluctuations impact economic stability. This support has helped stabilize Nigeria’s economy during crises, even though debt challenges persist.[19] Nigeria remains burdened by high debt, and its future development depends on balancing IMF recommendations with local priorities. Ongoing IMF assistance for debt management could help stabilize Nigeria’s economy, but long-term success will require effective resource utilization for diversified growth and political stability.[20] Debt-related issues can be observed in each of the case studies but handling of the issue differentiate as it can be seen in the case of Kenya, where diplomatic closeness to a world power gave it an advantage.

3.2 Kenya: American Relations and Economic Reforms

Kenya’s role as an East African economic hub and its close relationship with the U.S. significantly influence its interactions with the Bretton Woods institutions, particularly the World Bank. As a key U.S. ally in the region, Kenya receives substantial support for development and infrastructure projects funded by the World Bank. One notable initiative is the Kenya Urban Support Program, which aims to improve urban infrastructure and foster sustainable cities. [21] Additionally, the IMF has backed Kenya’s economic reforms, focusing on policies such as trade support and financial discipline to promote steady economic growth.[22]

However, Kenya’s rising public debt, exacerbated by the effects of climate change and a high cost of living, presents major challenges. In 2023, Kenya’s total debt reached concerning levels, prompting the IMF to introduce a program to help Kenya address this issue. This multi-year strategy aims to increase government revenue through tax reforms, prioritize public spending, and support vulnerable communities.[23] The IMF program also emphasizes strengthening governance by addressing inefficiencies in state-owned enterprises and enhancing anti-corruption measures.[24]

Critics argue that while these reforms are necessary, they often come at the cost of deepening social inequalities, as market reforms and privatization can adversely affect local industries and public services. Furthermore, a significant portion of Kenya’s revenue is allocated to debt repayment, which limits funding for essential services.[25] For Kenya to achieve sustainable growth, it is crucial to balance external financial support with local priorities, particularly in advancing social programs that serve lower-income communities. Kenya’s alignment with U.S. and World Bank policies suggests continued infrastructure growth and economic reform, though rising debt levels pose risks.

Kenya’s success will depend on balancing IMF and World Bank policies with domestic needs, especially concerning public spending and efforts to reduce inequality. These strategies should guide Kenya’s path toward steady growth and long-term stability.[26] While Kenya’s relations with the U.S. have provided an advantage in managing some economic challenges, South Africa has positioned itself as a partner with multiple major economic blocs, allowing for a more diversified approach.

3.3 South Africa: Balancing BRICS and Bretton Woods Institutions

South Africa’s relationship with the Bretton Woods institutions is unique due to its status as the most industrialized country in Sub-Saharan Africa and its membership in BRICS. Following the end of apartheid, the World Bank played a supportive role in South Africa’s reconstruction, funding projects aimed at reducing inequality and improving infrastructure.[27] Recently, the World Bank approved a $1 billion loan to assist South Africa’s transition to a “green and just” economy, though this initiative has raised concerns about balancing public benefit with the risks associated with private capital investments.[28] The IMF also provided crucial financial support during the COVID-19 pandemic to help stabilize South Africa’s economy.[29]

South Africa’s BRICS membership adds an additional layer of complexity, as BRICS provides an alternative to Western financial institutions like those within the Bretton Woods system. Through BRICS, South Africa can access the New Development Bank (NDB), which offers loans and grants without the conditionalities often imposed by the IMF or World Bank.[30] This dual alignment allows South Africa to benefit from both traditional Bretton Woods support and more flexible financing options through BRICS, enabling it to pursue diverse economic strategies.

While this dual engagement has given South Africa access to various forms of financial support, the country continues to face significant economic challenges, including high unemployment, persistent inequality, and a need for energy transition. South Africa’s future success relies on balancing its relationships with the IMF and World Bank alongside the flexibility of BRICS. This approach will be essential to achieving economic stability and growth in a complex global landscape.[31]

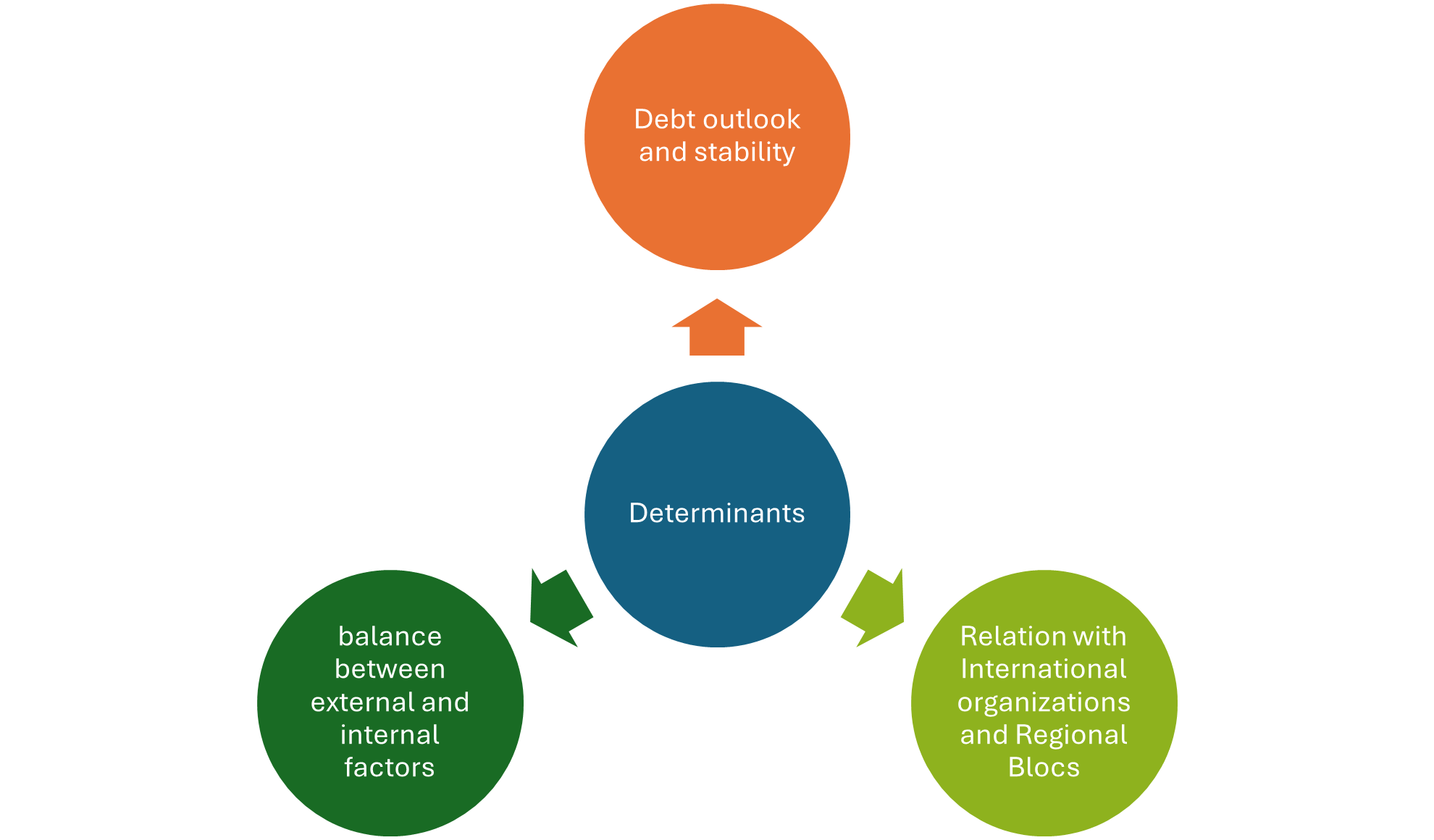

Figure 3: Determinants (suggestions)

4. Conclusion

The relationships of Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa with the Bretton Woods institutions reveal a mix of opportunities and challenges. Nigeria’s combination of oil wealth and a significant debt burden, Kenya’s alignment with U.S.-backed policies, and South Africa’s dual affiliation with both BRICS and the IMF/World Bank illustrate the complexities inherent in reliance on these institutions. As Sub-Saharan Africa seeks economic stability, finding the right balance between external partnerships and internal development policies will be essential for achieving long-term growth and integration into the global economy. Local initiatives focused on economic diversification, improved governance, and human capital investment will be pivotal for sustainable progress. For Sub-Saharan Africa, balancing engagement with Bretton Woods institutions while maintaining local autonomy will be key to fostering resilient, inclusive growth in the future.[32]

[1] Ben Steil, The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 17.

[2] World Bank, “The History of the World Bank,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/about/history.

[3] Barry Eichengreen, Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System, 2nd ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 91.

[4] International Monetary Fund, “The IMF at a Glance,” https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-at-a-Glance.

[5] World Bank Group, “Overview of Sub-Saharan Africa,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/overview.

[6] Brookings Institution, “Africa’s Labor Market: Challenges and Opportunities,” https://www.brookings.edu/articles/africas-labor-market-potential.

[7] Sarah Bracking, Money and Power: Great Predators in the Political Economy of Development (London: Pluto Press, 2009), 38-39.

[8] Debt Management Office, “Nigeria’s Total Public Debt Stock as at March 31, 2024,” https://www.dmo.gov.ng/debt-profile/total-public-debt/4731-nigeria-s-total-public-debt-stock-as-at-march-31-2024/file.

[9] “South Africa Overview,” World Bank, accessed October 21, 2024, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/southafrica/overview.

[10] “World Bank’s $1 billion loan to South Africa risks green and just transformation,” Bretton Woods Project, July 2024, https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2024/07/world-banks-1-billion-loan-to-south-africa-risks-green-and-just-transformation-by-doubling-down-on-de-risking-private-capital/.

[11] “Debt Relief for Nigeria,” Center for Global Development, https://www.cgdev.org/page/debt-relief-nigeria.

[12] “Fiscal Policy Options for Growing Out of Debt: Evidence from Nigeria,” Brookings Institution, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/fiscal-policy-options-for-growing-out-of-debt-evidence-from-nigeria.

[13] “BRICS Summit 2024: South Africa’s Role,” GIS Reports Online, October 2024, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/brics-summit-2024-south-africa/.

[14] International Monetary Fund, “The IMF at a Glance,” https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-at-a-Glance.

[15] Barry Eichengreen, Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System, 2nd ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 91.

[16] “World Bank’s $1 billion loan to South Africa risks green and just transformation,” Bretton Woods Project, July 2024, https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2024/07.

[17] International Monetary Fund, “IMF Report on Africa’s Economic Outlook 2023,” https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/Africa-debt-report.

[18] Sarah Bracking, Money and Power: Great Predators in the Political Economy of Development (London: Pluto Press, 2009), 45-46.

[19] World Bank, “The History of the World Bank,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/about/history.

[20] Debt Management Office, “Nigeria’s Total Public Debt Stock as at March 31, 2024,” https://www.dmo.gov.ng/debt-profile/total-public-debt/4731-nigeria-s-total-public-debt-stock-as-at-march-31-2024/file.

[21] World Bank Group, “Overview of Sub-Saharan Africa,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/overview.

[22] “Kenya Urban Support Program,” World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/10/30/kenya-urban-support-program.

[23] International Monetary Fund, “The IMF at a Glance,” https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-at-a-Glance.

[24] World Bank, “Kenya Economic Update: Navigating the Pandemic,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kenya/publication/kenya-economic-update.

[25] “Africa’s Labor Market: Challenges and Opportunities,” Brookings Institution, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/africas-labor-market-potential.

[26] IMF Report: “Africa’s Economic Outlook 2023,” International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/Africa-debt-report.

[27] Vishnu Padayachee, ed., The Political Economy of Africa, 225-230.

[28] “South Africa Overview,” World Bank, accessed October 21, 2024, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/southafrica/overview.

[29] “BRICS Summit 2024: South Africa’s Role,” GIS Reports Online, October 2024, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/brics-summit-2024-south-africa/.

[30] “Kenya Urban Support Program,” World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/10/30/kenya-urban-support-program.

[31] World Bank, “Kenya Economic Update: Navigating the Pandemic,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kenya/publication/kenya-economic-update.

[32] Ben Steil, The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 17.

The Role of Bretton Woods Institutions in Shaping Economic Strategies in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Case Study of Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa

Rashed Hasan Alhosani

- Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa has grown into a region of increasing significance in the global economic landscape, and its relationship with international organizations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been crucial in shaping its development trajectory. Despite a wealth of resources and a young, dynamic population, Sub-Saharan Africa faces unique economic challenges. How have the IMF and the World Bank influenced the development of key African economies, and what role do these institutions play in navigating the regional economic stability?[1]

This paper examines the relationships between Sub-Saharan Africa and the Bretton Woods institutions, focusing specifically on Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa. These countries’ interactions with the IMF and the World Bank illustrate the varying influence of these institutions on the region’s economic strategies. Nigeria, with its resource-rich economy, faces complex debt and development challenges. Kenya, positioned as an East African economic hub, aligns with U.S.-backed policies in pursuit of growth. Meanwhile, South Africa, the continent’s most industrialized nation and a BRICS member, represents an alternative approach by balancing traditional IMF/World Bank relations with emerging economic partnerships. Each case study illustrates the broader implications of Bretton Woods engagement for Sub-Saharan Africa.[2]

This analysis is based on historical data, economic reports, and direct insights from the World Bank and IMF. By examining economic policies, development programs, and growth metrics influenced by Bretton Woods institutions, the paper provides a detailed evaluation of these relationships. Quantitative data, including recent reports from the IMF and World Bank, support the analysis of each case study.[3]

- Theoretical Framework Clarifying key terms and organizations relevant to this paper is essential for enhancing the reader’s understanding throughout. Therefore, this section addresses three foundational aspects: a brief history of the Bretton Woods institutions and their inception, an overview of the economic context in the Sub-Saharan region, and an exploration of the link between the two. These elements will set the stage for a clearer discussion of the topic in the subsequent sections.

2.1 Brief History of Bretton Woods

The Bretton Woods system was established in July 1944 at the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, held at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, U.S. Forty-four nations gathered to design a new international monetary system aimed at ensuring economic stability and preventing crises like those experienced during the Great Depression and the two world wars.[4] The outcome of the conference was the creation of two major financial institutions: the IMF and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which later became part of the World Bank Group.[5]

The IMF was initially responsible for overseeing a system of fixed exchange rates, where currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar, while the World Bank primarily focused on post-war reconstruction and long-term economic development in struggling nations.[6] Although the fixed exchange rate system eventually collapsed in the 1970s, the IMF and World Bank have endured, adapting to the evolving global financial landscape. Today, these institutions play pivotal roles in providing financial assistance and policy guidance to countries worldwide, particularly to developing economies that seek economic stability and growth,[7] like Sub-Saharan Africa.

2.2 Economic Context of Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa, known for its abundant natural resources and cultural diversity, has long faced economic challenges rooted in colonial legacies, political instability, and widespread poverty. The region comprises many low-income countries that struggle with limited funding, high borrowing costs, and substantial debt-related risks. Despite these obstacles, Sub-Saharan Africa possesses valuable resources, including oil, gas, and minerals, that—if effectively managed—hold the potential to enhance financial stability. In recent years, however, economic difficulties have deepened as many nations struggle to mobilize domestic resources to meet financial obligations. Low-income countries in the region now need over $70 billion annually—about 6 percent of their GDP—for the next four years to manage their finances effectively.[8] This financial strain has led governments to reduce essential public services and redirect funds intended for development toward debt repayment, hindering long-term growth prospects.[9]

Despite these challenges, Sub-Saharan Africa has significant opportunities for development, particularly due to its youthful population and the potential for human capital investment. With a projected population increase of 740 million by 2050, the region could benefit from policies promoting economic diversification, education, and job creation. However, current job creation rates fall short of accommodating the approximately 12 million young people entering the workforce each year.[10] The region’s dependence on external support, particularly from the IMF and World Bank, underscores the need for strategies that strengthen economic resilience, improve governance, and promote sustainable growth.[11]

Figure 1: World Bank projects in Sub-Saharan Africa

Source: worldbank.org

2.3 Link Between Bretton Woods and Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa’s engagement with the Bretton Woods institutions has profoundly influenced its economic policies and development paths. Both the IMF and the World Bank play critical roles in shaping the region’s strategies for growth, offering financial resources, policy recommendations, and technical assistance. Each case study—Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa—illustrates a unique aspect of the region’s relationship with these institutions, reflecting various degrees of dependency, alignment, and adaptation. While these institutions aim to promote stability and growth, they have also been criticized for promoting policies that sometimes overlook local needs and exacerbate social inequalities. The Bretton Woods institutions’ influence in Sub-Saharan Africa highlights the complex balance between global financial systems and the autonomy of developing nations in determining their own economic futures.[12] This can be observed particularly with the case studies that this paper focuses on.

Figure 2: Case studies’ challenges

Source: author

- Case Studies

In the case of Nigeria, the IMF and World Bank have frequently provided financial assistance to manage the country’s high debt levels, often tied to fluctuations in global oil prices. These interventions have been pivotal during periods of economic instability but have also resulted in complex debt-servicing challenges that continue to impact Nigeria’s fiscal policy.

Kenya’s relationship with the Bretton Woods institutions has also been significant, particularly as it navigates its role as a key East African economy. American influence, both through direct aid and policy alignment, has played a central role in Kenya’s economic reforms, particularly in infrastructure development and poverty reduction programs supported by the World Bank. This relationship with the U.S. will be explored as a critical aspect of Kenya’s engagement with the global financial system.

South Africa offers a unique case with its involvement in BRICS, which has complicated its relationship with the Bretton Woods institutions. As South Africa balances its BRICS membership with IMF and World Bank engagement, its economic strategies reflect a dual alignment with both Western and emerging economies, highlighting the complexities of its global economic positioning.

3.1 Nigeria: Managing High Debt

Nigeria, with a population of around 202 million, stands as one of the largest economies in Sub-Saharan Africa and serves as a key case study in exploring the region’s relationship with the Bretton Woods institutions. Known for its vast natural resources, particularly oil, Nigeria’s wealth places it in a unique position among Sub-Saharan African nations. However, despite its economic potential, Nigeria is also one of the continent’s most indebted nations, with public debt reaching $121.67 billion as of March 2024. External debt alone is $36 billion,[13] while nearly 100 million Nigerians live on less than a dollar per day, reflecting inequality in resource distribution.[14]

IMF and World Bank interventions in Nigeria are largely driven by the country’s high debt levels and the volatility of global oil prices, which directly affect the economy.[15] Between 2012 and 2023, Nigeria’s debt increased by 123%, largely due to externally sourced loans that raise concerns over sustainability. Global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict, have further complicated Nigeria’s economic stability, leading to rising inflation and increased poverty rates.[16] The World Bank has been a crucial partner in Nigeria’s development efforts, providing $12.2 billion from 2021 to 2024 to support diverse projects aimed at poverty alleviation, job creation, and social service utilization.[17]

While Bretton Woods interventions aim to stabilize Nigeria’s economy, they often come with conditions that require Nigeria to implement stern fiscal policies. These include the reduction of subsidies and diversification away from oil dependency, which, although beneficial in the long term, have proven politically challenging for Nigeria’s leadership. The World Bank also supports conflict-affected regions, such as North-East Nigeria, where efforts focus on strengthening livelihoods and promoting sustainable development.[18] Statistics show that as Africa’s top oil exporter, Nigeria’s high debt levels have led to substantial IMF interventions, especially when oil price fluctuations impact economic stability. This support has helped stabilize Nigeria’s economy during crises, even though debt challenges persist.[19] Nigeria remains burdened by high debt, and its future development depends on balancing IMF recommendations with local priorities. Ongoing IMF assistance for debt management could help stabilize Nigeria’s economy, but long-term success will require effective resource utilization for diversified growth and political stability.[20] Debt-related issues can be observed in each of the case studies but handling of the issue differentiate as it can be seen in the case of Kenya, where diplomatic closeness to a world power gave it an advantage.

3.2 Kenya: American Relations and Economic Reforms

Kenya’s role as an East African economic hub and its close relationship with the U.S. significantly influence its interactions with the Bretton Woods institutions, particularly the World Bank. As a key U.S. ally in the region, Kenya receives substantial support for development and infrastructure projects funded by the World Bank. One notable initiative is the Kenya Urban Support Program, which aims to improve urban infrastructure and foster sustainable cities. [21] Additionally, the IMF has backed Kenya’s economic reforms, focusing on policies such as trade support and financial discipline to promote steady economic growth.[22]

However, Kenya’s rising public debt, exacerbated by the effects of climate change and a high cost of living, presents major challenges. In 2023, Kenya’s total debt reached concerning levels, prompting the IMF to introduce a program to help Kenya address this issue. This multi-year strategy aims to increase government revenue through tax reforms, prioritize public spending, and support vulnerable communities.[23] The IMF program also emphasizes strengthening governance by addressing inefficiencies in state-owned enterprises and enhancing anti-corruption measures.[24]

Critics argue that while these reforms are necessary, they often come at the cost of deepening social inequalities, as market reforms and privatization can adversely affect local industries and public services. Furthermore, a significant portion of Kenya’s revenue is allocated to debt repayment, which limits funding for essential services.[25] For Kenya to achieve sustainable growth, it is crucial to balance external financial support with local priorities, particularly in advancing social programs that serve lower-income communities. Kenya’s alignment with U.S. and World Bank policies suggests continued infrastructure growth and economic reform, though rising debt levels pose risks.

Kenya’s success will depend on balancing IMF and World Bank policies with domestic needs, especially concerning public spending and efforts to reduce inequality. These strategies should guide Kenya’s path toward steady growth and long-term stability.[26] While Kenya’s relations with the U.S. have provided an advantage in managing some economic challenges, South Africa has positioned itself as a partner with multiple major economic blocs, allowing for a more diversified approach.

3.3 South Africa: Balancing BRICS and Bretton Woods Institutions South Africa’s relationship with the Bretton Woods institutions is unique due to its status as the most industrialized country in Sub-Saharan Africa and its membership in BRICS. Following the end of apartheid, the World Bank played a supportive role in South Africa’s reconstruction, funding projects aimed at reducing inequality and improving infrastructure.[27] Recently, the World Bank approved a $1 billion loan to assist South Africa’s transition to a “green and just” economy, though this initiative has raised concerns about balancing public benefit with the risks associated with private capital investments.[28] The IMF also provided crucial financial support during the COVID-19 pandemic to help stabilize South Africa’s economy.[29]

South Africa’s BRICS membership adds an additional layer of complexity, as BRICS provides an alternative to Western financial institutions like those within the Bretton Woods system. Through BRICS, South Africa can access the New Development Bank (NDB), which offers loans and grants without the conditionalities often imposed by the IMF or World Bank.[30] This dual alignment allows South Africa to benefit from both traditional Bretton Woods support and more flexible financing options through BRICS, enabling it to pursue diverse economic strategies.

While this dual engagement has given South Africa access to various forms of financial support, the country continues to face significant economic challenges, including high unemployment, persistent inequality, and a need for energy transition. South Africa’s future success relies on balancing its relationships with the IMF and World Bank alongside the flexibility of BRICS. This approach will be essential to achieving economic stability and growth in a complex global landscape.[31]

Figure 3: Determinants (suggestions)

- Conclusion

The relationships of Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa with the Bretton Woods institutions reveal a mix of opportunities and challenges. Nigeria’s combination of oil wealth and a significant debt burden, Kenya’s alignment with U.S.-backed policies, and South Africa’s dual affiliation with both BRICS and the IMF/World Bank illustrate the complexities inherent in reliance on these institutions. As Sub-Saharan Africa seeks economic stability, finding the right balance between external partnerships and internal development policies will be essential for achieving long-term growth and integration into the global economy. Local initiatives focused on economic diversification, improved governance, and human capital investment will be pivotal for sustainable progress. For Sub-Saharan Africa, balancing engagement with Bretton Woods institutions while maintaining local autonomy will be key to fostering resilient, inclusive growth in the future.[32]

[1] Ben Steil, The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 17.

[2] World Bank, “The History of the World Bank,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/about/history.

[3] Barry Eichengreen, Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System, 2nd ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 91.

[4] International Monetary Fund, “The IMF at a Glance,” https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-at-a-Glance.

[5] World Bank Group, “Overview of Sub-Saharan Africa,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/overview.

[6] Brookings Institution, “Africa’s Labor Market: Challenges and Opportunities,” https://www.brookings.edu/articles/africas-labor-market-potential.

[7] Sarah Bracking, Money and Power: Great Predators in the Political Economy of Development (London: Pluto Press, 2009), 38-39.

[8] Debt Management Office, “Nigeria’s Total Public Debt Stock as at March 31, 2024,” https://www.dmo.gov.ng/debt-profile/total-public-debt/4731-nigeria-s-total-public-debt-stock-as-at-march-31-2024/file.

[9] “South Africa Overview,” World Bank, accessed October 21, 2024, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/southafrica/overview.

[10] “World Bank’s $1 billion loan to South Africa risks green and just transformation,” Bretton Woods Project, July 2024, https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2024/07/world-banks-1-billion-loan-to-south-africa-risks-green-and-just-transformation-by-doubling-down-on-de-risking-private-capital/.

[11] “Debt Relief for Nigeria,” Center for Global Development, https://www.cgdev.org/page/debt-relief-nigeria.

[12] “Fiscal Policy Options for Growing Out of Debt: Evidence from Nigeria,” Brookings Institution, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/fiscal-policy-options-for-growing-out-of-debt-evidence-from-nigeria.

[13] “BRICS Summit 2024: South Africa’s Role,” GIS Reports Online, October 2024, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/brics-summit-2024-south-africa/.

[14] International Monetary Fund, “The IMF at a Glance,” https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-at-a-Glance.

[15] Barry Eichengreen, Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System, 2nd ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 91.

[16] “World Bank’s $1 billion loan to South Africa risks green and just transformation,” Bretton Woods Project, July 2024, https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2024/07.

[17] International Monetary Fund, “IMF Report on Africa’s Economic Outlook 2023,” https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/Africa-debt-report.

[18] Sarah Bracking, Money and Power: Great Predators in the Political Economy of Development (London: Pluto Press, 2009), 45-46.

[19] World Bank, “The History of the World Bank,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/about/history.

[20] Debt Management Office, “Nigeria’s Total Public Debt Stock as at March 31, 2024,” https://www.dmo.gov.ng/debt-profile/total-public-debt/4731-nigeria-s-total-public-debt-stock-as-at-march-31-2024/file.

[21] World Bank Group, “Overview of Sub-Saharan Africa,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/overview.

[22] “Kenya Urban Support Program,” World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/10/30/kenya-urban-support-program.

[23] International Monetary Fund, “The IMF at a Glance,” https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-at-a-Glance.

[24] World Bank, “Kenya Economic Update: Navigating the Pandemic,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kenya/publication/kenya-economic-update.

[25] “Africa’s Labor Market: Challenges and Opportunities,” Brookings Institution, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/africas-labor-market-potential.

[26] IMF Report: “Africa’s Economic Outlook 2023,” International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/Africa-debt-report.

[27] Vishnu Padayachee, ed., The Political Economy of Africa, 225-230.

[28] “South Africa Overview,” World Bank, accessed October 21, 2024, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/southafrica/overview.

[29] “BRICS Summit 2024: South Africa’s Role,” GIS Reports Online, October 2024, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/brics-summit-2024-south-africa/.

[30] “Kenya Urban Support Program,” World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/10/30/kenya-urban-support-program.

[31] World Bank, “Kenya Economic Update: Navigating the Pandemic,” https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kenya/publication/kenya-economic-update.

[32] Ben Steil, The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 17.