Contemporary security dynamics require a reevaluation of military doctrine, where conventional indicators of capability, like firepower and advanced technology, need to balance environmental sustainability. The shifting global climate, based on environmental degradation, diminishing resource availability, and growing societal oversight, places armed forces in a contradictory situation. While militaries must preserve combat integrity to counter multifaceted geopolitical challenges, they also face heightened pressure to reduce their ecological footprint. Activities ranging from major deployments and supply chains to energy-heavy production of armaments and machinery are unavoidably resource-intensive, affecting environmental weaknesses and playing a notable role in greenhouse gas output.

In this context, sustainable military innovations are no longer superficial demonstrations of ecological awareness but practical necessities. Developments such as compostable munitions, environmentally safe propellants, and less wasteful production techniques are transitioning from marginal trials to crucial elements in contemporary defense planning. Integrating environmental considerations into military strategy enables forces to improve supply chain adaptability and lower mission hazards while strengthening their global reputation. Initiatives such as the U.S. Department of Defense’s (DoD) extensive trials with eco-friendly ammunition[1] and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s (NATO) Smart Energy Program[2] demonstrate the practical effectiveness of sustainable military technologies. This suggests that green alternatives can endure harsh operational conditions, challenging common assumptions regarding their stability and effectiveness.

This paper highlights how eco-friendly advancements in defense systems do not just supplement conventional methods; they significantly increase military potential. Environmental approaches directly boost strategic proficiency by minimizing fuel supply risks, optimizing logistical networks, and refining rapid response capabilities. Additionally, as global governance grows progressively attuned to ecological concerns, armed forces embracing sustainable technology will secure greater geopolitical influence, shaping cooperative agreements, multinational operations, and societal approval. Responsible military power is not just a moral concept for periods of peace; it serves as a crucial strategic asset, determining combat superiority and reinforcing global authority where ecological responsibility and operational durability are further interconnected.

The Technological Shift Toward Eco-Friendly Defense

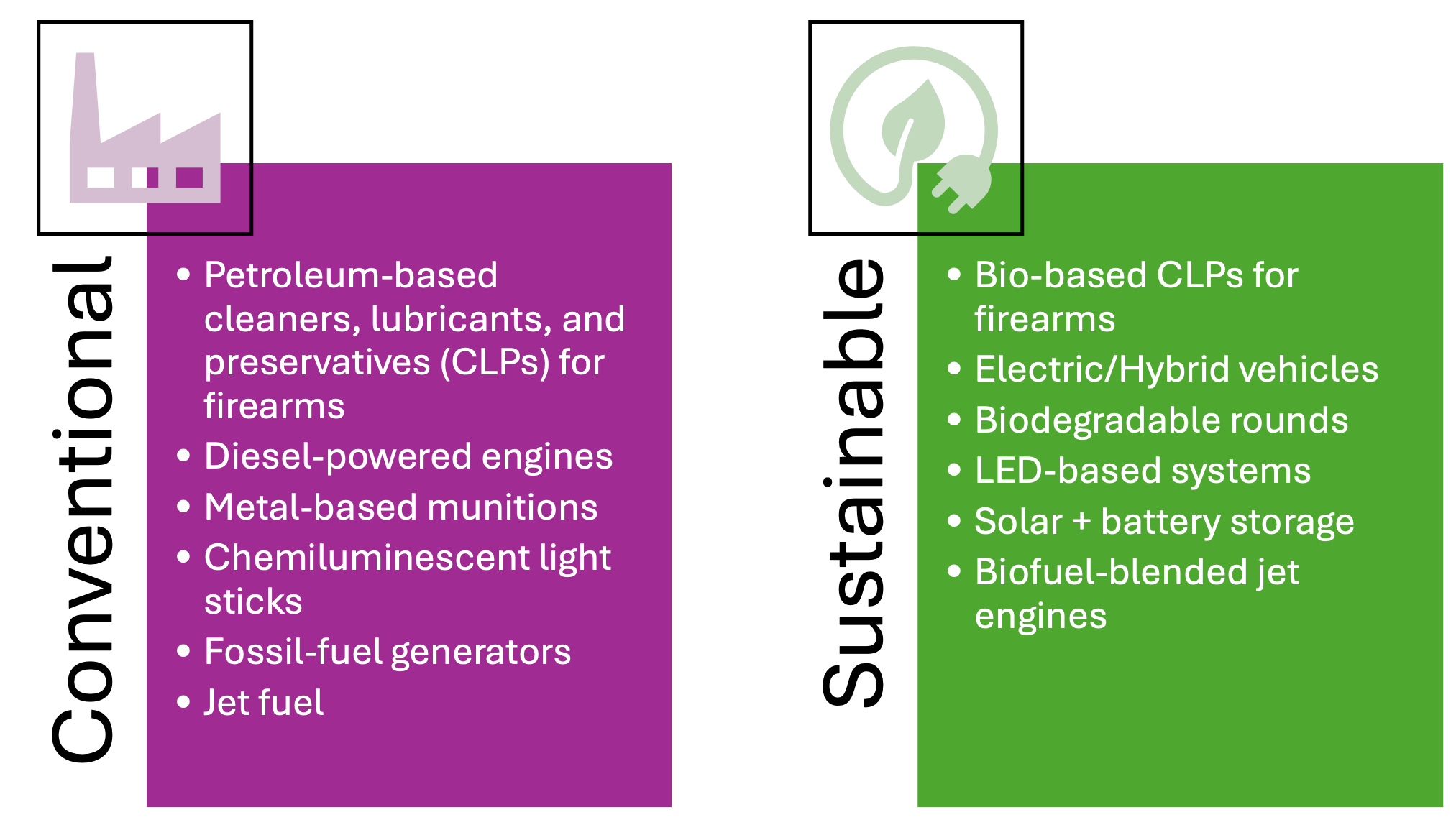

Contemporary defense is transitioning toward newer technological and strategic goals, which are driven by the dual imperatives of maintaining military advantage, yet still addressing environmental responsibility. Emerging sustainability measures, including decomposable munitions, environmentally safer propellants, and electric-powered military vehicles, are challenging older operational doctrines while demonstrating that environmental priorities can align with mission standards. Rather than reducing performance, green technologies offer practical advantages through stronger logistical resilience, fewer tactical liabilities, and more efficient resource use.[3] Biodegradable munitions highlight this transition, minimizing pollution linked to traditional metal-based projectiles. Such ammunition breaks down into harmless substances after use, reducing environmental harm during training exercises and combat missions.[4] Similarly, non-toxic propellants decrease harmful substance exposure for personnel while reducing ecological harm, ensuring training areas and battlegrounds remain viable for prolonged operational use. Electric military vehicles, ranging from tactical supply carriers to armored transports, deliver notable improvements in reduced noise and thermal signatures, considerably decreasing detection risks on the battlefield.[5]

Nevertheless, the move toward sustainability within the defense industry still faces skepticism, stemming from experiences based on the lack of tactical efficacy. In 2011, during the U.S. Navy’s Green Fleet trial, the branch spent around $27 per gallon on biofuel, nearly ten times the price of traditional fuel, leading Defense Department leaders to doubt whether such expensive and scarce biofuel supply systems could support large-scale, high-intensity operations globally.[6] Even so, real-world applications by key defense entities, particularly the U.S. DoD and NATO, prove that sustainability and combat efficiency can not only coexist but also mutually reinforce one another.

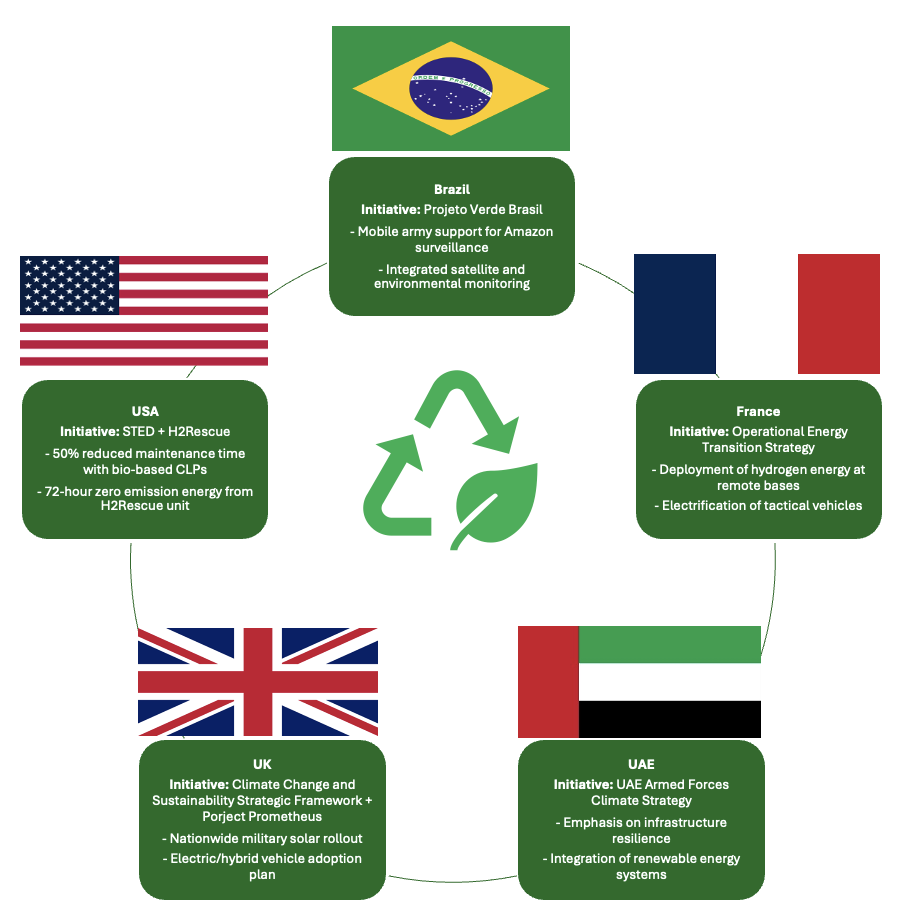

The U.S. DoD’s Sustainable Technology Evaluation and Demonstration (STED) initiative provides evidence backing the functional viability of green innovations. The initiative places technologies under field conditions to assess both performance outcomes and cost efficiency over time.[7] One notable success involved a bio-based cleaner, lubricant, and preservative tested by Marine Corps personnel. The findings showed a 50% decrease in firearm maintenance time, less carbon buildup, smoother operation, fewer breakdowns, and reduced lubricant use compared to standard petroleum-based alternatives.[8] These refinements directly correlate with heightened combat preparedness, weapon dependability, and logistical effectiveness. The bio-based formula was subsequently mandated for universal DoD implementation, confirming the strategic necessity of ecological innovation. Furthermore, sustainable construction methods tested under STED featured energy-efficient entry systems capable of drastically lowering power usage. If adopted across the entire department, these measures could save $170 million yearly, greatly improving financial adaptability and available resources.[9] Swapping out conventional chemiluminescent devices with LED alternatives led to observable benefits in field visibility, operational endurance during extended deployments, and fiscal savings over time. These outcomes support the case that green measures do not hinder performance. On the contrary, they enable smoother logistics, lower exposure to risk, and better resource allocation. The DoD’s program challenges prevailing misconceptions that eco-friendly measures inherently weaken combat potential. Mirroring U.S. efforts, NATO’s Smart Energy Program showcases how ecological efforts reinforce operational capacity. The initiative specifically targets merging solar power setups, lithium-ion battery units for frontline bases, and hybrid-electric drivetrains in tactical vehicle groups.[10] NATO’s strategy prioritizes renewable energy options, modern battery storage solutions, and hybrid-electric transports to cut down logistical burdens, especially susceptible fuel convoys.[11] Fuel supply routes have long been exposed to threats in asymmetric conflict areas, where adversary tactics frequently target supplies via ambushes or explosive traps. Throughout conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, fuel routes represented a disproportionately high number of losses and tactical setbacks.[12] NATO’s introduction of renewables and hybrid-electric technology addresses these vulnerabilities. On-site power generation paired with lower reliance on fossil fuels grants forces enhanced operational independence, reducing the need for precarious resupply runs.

Figure 1: Comparative Efficiency Outcomes of Military Technologies

Source: Author’s creation using Microsoft SmartArt

NATO-aligned initiatives also show that environmentally focused technologies can meet operational standards. Following NATO protocols, the Swedish Armed Forces performed successful test flights of the JAS 39 Gripen using a blend of jet fuel and plant-derived biofuel with no impact on performance.[13] At the same time, the UK trialed electric versions of the Foxhound armored vehicle that matched or surpassed standard performance criteria.[14] By 2025, the UK military aims to fully deploy hybrid-electric prototypes, demonstrating faith in their battlefield reliability.[15] Despite these advancements, the effectiveness lacks in certain environments, especially regarding electric or hydrogen-fuelled mechanisms that could fail during intense heat, cold, or uneven landscapes. Nevertheless, sustainable defense projects deliver tactical strengths, including lighter logistical footprints, better stealth qualities, and extended operational durability.[16]

Furthermore, this sustainability shift mitigates broader strategic constraints tied to fossil fuel reliance, most prominently the logistical challenges and related risks stemming from fuel transport. Renewable and electrified systems curtail dependence on insecure supply chains, thereby amplifying strategic adaptability. Armed forces are beginning to acknowledge sustainability globally as central to tactical effectiveness. The European Union (EU) has placed significant emphasis on sustainability within its defense policy, specifically aiming to lower emissions from field operations.[17] Likewise, the UAE Armed Forces’ climate strategy highlights sustainability as crucial for maintaining long-term combat effectiveness, asserting that eco-conscious methods strengthen resilience and adaptability against climate-related operational threats.[18] Additionally, the UAE stresses that sustainable transitions, rather than weakening security, enhance operational capacities by mitigating environmental risks and reinforcing infrastructure durability.[19]

Brazil provides a different yet equally revealing model. In 2023, its army introduced Projeto Verde Brasil, focusing on reduced military environmental harm within Amazon deployment zones. The project included the mobilization of temporary Army installations to assist ecological monitoring units in isolated Amazonian regions, facilitating strategic operations, safeguarding personnel, and sustaining substantial numbers of staff.[20] Brazil’s military utilized airborne surveillance, terrestrial and fluvial checkpoints, with patrol crafts to aid in deforestation control. Moreover, satellite-connected observation mechanisms were utilized alongside domestic agencies to reinforce both the armed forces and immediate environmental monitoring throughout Brazil’s Amazonian jurisdiction.[21] These initiatives not only underline Brazil’s capacity for merging ecological measures with ecologically sensitive areas but also signal awareness among rising powers that environmental responsibility supports regional stability and strategic mobility. Brazil’s initiatives emphasize sustainability’s relevance not solely within NATO or developed economies, but also across the Global South.

The DoD, working alongside the Department of Energy, contributed to H2Rescue, a zero-emission hydrogen fuel-cell emergency response unit able to provide power, heating, and potable water in disaster scenarios while mitigating carbon emissions. Developed by the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center, the prototype features an 18-unit hydrogen containment setup allowing for 180-mile mobility and 25 kilowatts of uninterrupted energy production spanning 72 hours, with potential uses in future military deployments.[22] Incorporating sustainability into military planning, far from detracting from readiness, yields tactical and strategic benefits. This effort aligns with a wider shift in the U.S. armed forces, wherein the DoD has acknowledged that adopting sustainable innovations such as hydrogen energy cells, plant-based fuels, and electric mobility can provide energy durability, lessen logistical weaknesses, and increase mission efficiency in both combat and relief scenarios.[23] These projects simplify resupply protocols, boost maneuverability within low-emission sectors, augment mission duration, and reduce ecological tolls. Field implementation in actual combat and training settings clarifies that ecological innovation is not a detriment but can be used as a strategic asset.

Integrating Sustainability into Defense Supply Chains

Military sustainability extends far beyond the battlefield. Instead, it starts in production facilities, R&D labs, and acquisition frameworks. Embedding eco-friendly principles into defense logistics and sourcing delivers key strategic benefits. These include strengthening long-term durability, lowering operational risks, and aligning military priorities with wider environmental goals. Green production in the defense industry means adopting methods that limit ecological harm by improving energy use, cutting waste, and selecting sustainable resources. Lifecycle assessments (LCAs) have become crucial methods, delivering thorough appraisals of ecological consequences across all phases of a product’s lifespan, spanning initial resource procurement to fabrication, active use, and eventual decommissioning.[24] Use of LCAs allows defense industries to identify crucial improvement zones, reducing the carbon cost of military equipment and field operations.

Defense firms are starting to acknowledge the practical and reputational benefits tied to sustainable production. BAE Systems has integrated ecological responsibility into its defense supply networks via the adoption of low-energy production techniques, embedding LCA instruments and collaborating with vendors to maintain adherence to strict ecological performance benchmarks.[25] Likewise, Rheinmetall has adopted sustainable production strategies through energy-conscious manufacturing processes and the application of circular economic frameworks,[26] illustrated by their sophisticated reprocessing of composite substances used in armored transport and weapon platforms. Such methods not only reduce direct emissions but also secondary ecological effects linked to supply networks. Corporate initiatives, like BAE Systems’ low-carbon materials or Rheinmetall’s composite reuse, demonstrate that eco-conscious production improves both practicality and ecological responsibility. Sustainable manufacturing diminishes logistical hazards and fortifies supply network robustness by weakening reliance on politically unstable materials, such as neodymium necessary for electric propulsion and lithium vital for energy retention mechanisms.[27]

Yet incorporating sustainability into armed forces procurement systems presents substantial practical and systemic barriers that impede wholesale adoption. Defense production hinges on intricate arrangements involving scarce minerals, power-heavy procedures, and precision elements, which are costly for being emission-neutral without jeopardizing manufacturing schedules. Earth-conscious substitutes frequently miss the ruggedness or dependability crucial for military settings, primarily during rigorous field use. Ethical procurement may introduce weak points in substituting established vendors with innovative, sustainability-approved suppliers that might affect logistical ties, generating choke points or restricted compatibility among partners. Strategists additionally grapple with aligning environmental directives against swift mobilization necessities, notably during hostilities or elevated manufacturing phases. Financial limitations further obstruct the transition, given that renewable substances and facility upgrades demand considerable initial costs without prompt functional benefits. Ecological substitutes can still achieve the expansiveness, steadfastness, and output of traditional production techniques. The EU, via its Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and European Defence Fund (EDF), has demonstrated this method by clearly imposing ecological stipulations in military procurement deals.[28] These structures integrate ecological accountability into defense programs, encouraging a broad transition toward sustainable production and sourcing in allied nations. In 2024, the EU reaffirmed its pledge by introducing a sweeping green defense program, “Strategic Compass 2025,” enforcing demanding ecological metrics for impending military procurements and missions.[29] Under this effort, newer defense agreements must adhere to strict environmental benchmarks. This guarantees renewable power integration and sustainable supplies become standard in European armed forces.

Likewise, the UK’s Defence Ministry has actively embedded sustainability for future purchasing decisions. Its “Climate Change and Sustainability Strategic Framework,” revised in 2024, requires the incorporation of environmentally sound innovations across military procedures.[30] This policy includes obligatory fuel conservation regulations, broad implementation of electric and hybrid transport, and extensive renewable power projects, including Project Prometheus, which installed solar panel networks across British military sites to boost energy independence and curtail fossil fuel reliance.[31] NATO has likewise established aggressive sustainability objectives, striving for carbon neutrality by 2050.[32] Consistent with this target, the U.S. Army launched its “Electric Vehicle Transition Plan” in 2023, pursuing the electrification of major portions of its combat and support vehicle fleets by 2035.[33] At the same time, the military is expanding renewable energy efforts in home and foreign installations. This cuts fossil fuel reliance and increases operational stability against unpredictable energy markets and broken supplier networks.

The integration of sustainability directly strengthens strategic resilience by addressing risks related to fossil fuel needs. Forces depending heavily on conventional fuels face growing exposure to logistics failures, geopolitical friction, and unstable fuel costs. Transitioning to renewables, hybrid-electric systems, and eco-friendly supplies grants troops greater independence, flexibility, and durability. This adjustment affects hazards tied to distribution, especially in contested or distant operational zones. Emerging firms have incorporated the adoption of sustainable supply chain approaches in defense. Uplift360, a British startup founded by veterans, secured substantial investment from the UK Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA) during 2023 to develop circular economy approaches aimed at recycling obsolete Kevlar vests and recovering high-strength carbon fibers.[34] Previously burned or trashed, these supplies now re-enter manufacturing cycles. This notably decreases both ecological impact and buying expenses. Initiatives like Uplift360 highlight how green practices can innovate defense supply chains. They support self-sufficiency, cut supplier reliance, and expand operational sustainability.

Despite notable progress, major constraints persist in making defense supply chains sustainable. The sector remains a leading source of greenhouse gases, with noticeable emissions from production, logistics, and mission use. Full-scale decarbonization plans are required to manage these emissions. Such strategies need thorough energy reviews, smarter resource handling, and tight partnerships with eco-conscious vendors.

Eco-Deterrence and Strategic Legitimacy

As awareness of climate challenges grows worldwide, armies around the world face mounting pressure to balance conventional security roles with ecological leadership. This evolving framework, termed eco-deterrence, merges environmental considerations with defense planning, impacting perceptions of national credibility and combat integrity. When military organizations implement greener operational norms, they reduce environmental harm while boosting their strategic position globally, crafting reputations as reliable global partners committed to sustainability.

Ecological responsibility impacts international diplomatic leverage. In an era where climate issues dominate global discourse, countries that pioneer ecological reforms within defense architectures often command greater diplomatic esteem, facilitating stronger coalition building and tactical alliances. The United Nations continues to prioritize climate-conscious initiatives in peacekeeping, showing how embedding ecological concerns into defense activities can improve a country’s global reputation.[35] UN Peacekeeping missions have gradually included ecological accountability as a central aspect of their functions, declaring openly in regulatory documents that minimizing the environmental impact of such operations is essential for overall effectiveness.[36] Key measures include innovations such as battle camp solar arrays, wastewater repurposing infrastructure, and stringent toxic material protocols that safeguard local wildlife, reducing operational impact on surrounding habitats. These efforts reinforce the credibility of UN missions by connecting them to wider global priorities, such as the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, notably Objectives 13 and 16 concerning climate measures and stable governance, thereby supporting greater confidence and collaboration within the global community.[37]

Nordic states and French programs exemplify how green defense policy strengthens diplomatic weight while ensuring domestic credibility. Nordic states, including Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Denmark, have jointly pursued ambitious climate-focused defense strategies, leveraging their authority in environmental responsibility as a geopolitical instrument.[38] Via cooperative ventures, these governments advocate sustainable armed forces methods, improving local partnerships while projecting identities as visionary world leaders committed to ecological stability. Likewise, France has successfully incorporated ecological deterrence via programs such as its Operational Energy Transition Strategy, designed to support strategic independence by embracing renewable energy technologies inside its military forces.[39] Recent developments are seen in electric tactical transport and hydrogen energy solutions for remote bases, reducing logistical weaknesses while showcasing environmental dedication during high-profile summits and climate discussions.

Adopting green military methods offers benefits to the battlefield. Reducing reliance on traditional fuels both lessens supply chain risks and improves tactical mobility. Contemporary engagements repeatedly highlight the combat merits of efficient energy use, where conventional power options, mainly petrol derivatives, introduce substantial operational hazards. Extended fuel networks supporting resource-heavy missions prove susceptible to sabotage and interruption, undermining both mission success and soldier welfare. Consequently, forces investing in renewables and cleaner tech gain mobility advantages by simplifying logistics while achieving greater self-reliance, thus boosting adaptability across varied warzone conditions.

The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung highlights how militaries worldwide are integrating eco-friendly weapons and technologies. At the Korea Army International Defence Exhibition, South Korean companies showcased “eco-friendly” technologies, including lead-free ammunition and carbon-neutral weapon systems.[40] Though counterintuitive initially, their tactical value proves significant. Cleaner ordnances minimize ecological pollution, especially crucial in jungle warfare or protected conflict zones, preventing long-term environmental harm. Such ammunition additionally improves compliance with international ecological norms, strengthening institutional standing both at climate negotiations and during domestic environmental reviews. Even as the contradiction of environmentally conscious warfare remains contested, deploying sustainable munitions and cleaner technologies aids in reducing field pollution, thus strengthening military justification in both political and domestic strategies.[41]

Britain’s defense sustainability blueprint illustrates eco-deterrence through homegrown schemes like its energy sovereignty objectives and renewables development programs. Acknowledging climate shifts as an instability catalyst, the UK stresses readiness via renewable power developments and eco-conscious base management.[42] Enhancing military accommodation and infrastructure for energy efficiency not only cuts emissions but also improves troop welfare, indirectly boosting morale and performance. The UK’s approach reveals how green initiatives can synchronize ecological, tactical, and strategic aims, strengthening its NATO role and sway over climate-security policies. Similarly, France’s Operational Energy Transition Strategy proves that eco-innovation can play a role in combat operations, enhancing energy resilience, easing supply burdens, and protecting strategic independence. Initiatives funded by the UK’s Defence and Security Accelerator, such as hybrid battery logistics and hydrogen field generators, highlight how environmental stewardship reshapes military supply networks, solidifying strategic credibility.

Figure 2: Defense Sustainability Initiatives

Author’s creation using Microsoft SmartArt

Eco-deterrence gains legitimacy through projects such as NATO’s Climate and Security Action Plan and the EU’s 2024 Environmental Defence Directive, which embed green metrics into mission planning and procurement. NATO now treats climate change as a tactical and doctrinal priority, ensuring conservation into its frameworks to improve alliance cohesion. Meanwhile, EU tools like PESCO and the EDF green procurement with lifecycle carbon tracking directly impact reviews, pushing innovations like clean propulsion and recyclable hardware, which cement bloc-wide climate leadership. These cases show how green defense methods boost global credibility and deterrence. Meeting ecological standards improves national reputation, expanding diplomatic influence. Environmental scrutiny also reduces operational backlash, easing foreign collaboration. Practical perks like fewer fuel needs ensure resistance and adaptability, underpinning deterrence. Eco-deterrence frames militaries as forward-thinking actors managing modern risks, sharpening their strategic edge. The rise of eco-deterrence marks a potential turning point in defense doctrine. With climate concerns vital to global politics, forces incorporating sustainability into operations gain diplomatic weight, sharper agility, and firmer legitimacy.

Conclusion

Sustainability now functions as a key aspect of modern defense, influencing not only battlefield dynamics but also broader strategic outcomes. What once seemed like an environmental concern has evolved into a vital factor impacting military capability, geopolitical influence, and long-term stability. Armed forces that integrate eco-adapted systems, ranging from biodegradable munitions and low-toxicity fuels to electrified transport and decentralized energy platforms, can further reduce exposure to supply chain threats. It has been demonstrated that environmentally conscious defense models support military performance. NATO’s Smart Energy Program highlights this, showing how renewable systems and hybrid-electric units reduce exposure to fuel convoy attacks while enhancing battlefield endurance. In parallel, the U.S. Department of Defense’s STED initiative has validated the utility of greener components, including plant-based lubricants and energy-saving equipment, resulting in lower operational expenditures and longer equipment lifespans.

Beyond tactical gains, military forces that act on environmental priorities can strengthen their diplomatic standing. Climate-aware defense policy enhances trust and credibility, which can translate into more durable partnerships. France and the Nordic states have already shown how military strategy aligned with climate goals can amplify a country’s influence in both defense alliances and climate negotiations. To capitalize on these advantages, policy frameworks must evolve. Investment in defense R&D should prioritize energy-efficient platforms and recyclable systems. NATO members and their partners can lead this effort by embedding environmental standards in procurement and operational planning. Public-private ventures like the UK’s DASA-backed Uplift360, which recycles military-grade materials, also offer viable models for expanding sustainable innovation across defense industries.

Eco-adapted warfare is not a luxury or symbolic gesture. It is a practical shift that enhances readiness, improves strategic flexibility, and supports the values that many allied democracies claim to defend. As NATO deployments and U.S. defense trials have shown, this transformation is not only feasible but also already underway. In a world where military credibility is tied not just to force projection but to ethical conduct and resilience, choosing sustainable defense practices is a strategic choice grounded in necessity.

[1] Green Ammo, AS, “Green Ammo Secures Contracts with U.S. Department of Defence to Deliver Nearly 1,300 E-Blanks Training Kits Amid Global Blank Ammunition Shortage,” GlobeNewswire, October 16, 2024, https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2024/10/16/2963888/0/en/Green-Ammo-Secures-Contracts-with-U-S-Department-of-Defense-to-Deliver-Nearly-1-300-E-Blanks-Training-Kits-Amid-Global-Blank-Ammunition-Shortage.html.

[2] North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), “Environment, Climate Change and Security,” Last modified July 18, 2024, Accessed June 30, 2025, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_91048.htm.

[3] Aisha Issa, Amir Khadem, Ahmad Alzubi, and Ayşen Berberoğlu, “The Path from Green Innovation to Supply Chain Resilience: Do Structural and Dynamic Supply Chain Complexity Matter?” Sustainability 16, no. 9 (2024): 3762, https://doi.org/10.3390/su16093762.

[4] Rob Smith, “Environmentally Friendly Ammunition,” Gun Trade World, April 16, 2021, https://www.guntradeworld.com/environmentally-friendly-ammunition.

[5] Andreas Heldwein, “Emerging Electrification of Military Ground Systems,” Power Systems Design, July 1, 2025, https://www.powersystemsdesign.com/articles/emerging-electrification-of-military-ground-systems/154/22887.

[6] Mark F. Cancian, “Sink the Great Green Fleet,” Proceedings 143, no. 9 (September 2017), U.S. Naval Institute, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2017/september/sink-great-green-fleet.

[7] David Vergun, “DOD Tests and Evaluates Improved and Sustainable Technologies,” U.S. Department of Defense, October 3, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3925229/dod-tests-and-evaluates-improved-and-sustainable-technologies/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] NATO, “Energy Security,” Last updated January 11, 2024, Accessed July 3, 2025, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_49208.htm.

[11] Ana Gogoreliani, Fabio Indeo, and Teimuraz Puluzashvili, Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Solutions in NATO and PfP Countries’ Military Operations: Final Report of the Study, Vilnius, Lithuania: NATO Energy Security Centre of Excellence, July 2021, https://www.enseccoe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/2021-09.pdf.

[12] Adam Tiffen, “Going Green on the Battlefield Saves Lives,” War on the Rocks, May 22, 2014, https://warontherocks.com/2014/05/going-green-on-the-battlefield-saves-lives/.

[13] “Successful Tests with Fossil-Free Fuel,” Swedish Armed Forces, December 3, 2020, https://www.forsvarsmakten.se/en/news/2020/12/successful-tests-with-fossil-free-fuel/.

[14] Tom Barton, “IAV 2025: GDLS Preparing Mk 2 C2 Foxhound Variant, Soon to Finish Mk 1 Conversions,” Janes, January 22, 2025, https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-news/land/iav-2025-gdls-preparing-mk-2-c2-foxhound-variant-soon-to-finish-mk-1-conversions.

[15] Alistair Beard and Sarah Ashbridge. “Greening Defence: The British Army’s Bet on Electrification,” Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), March 23, 2022, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/greening-defence-british-armys-bet-electrification.

[16] Sustainability Directory, “Military Innovation,” Energy Sustainability Directory, April 26, 2025, https://energy.sustainability-directory.com/term/military-innovation/.

[17] Christoph Meyer, Edouard Simon, Francesca Vantaggiato, and Richard Youngs, Preparing the CSDP for the New Security Environment Created by Climate Change. In-depth analysis requested by the SEDE Subcommittee, Brussels: European Parliament, Directorate-General for External Policies, June 2021, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2021/653639/EXPO_IDA(2021)653639_EN.pdf.

[18] United Arab Emirates Ministry of Defence, UAE Armed Forces Climate Change Strategy 2023, MOD, 2023, https://mod.gov.ae/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Climate-Change-Strategy-EN.pdf.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Alexandre Baretta, “Operation Green Brazil: Contributions and Challenges for the Preservation of the Amazon,” Security and Land Power 4, no. 1 (2025): January–April, Lima: Peruvian Army Center for Strategic Studies, June 22, 2023, https://ceeep.mil.pe/2023/06/22/operacion-verde-brasil-contribuciones-y-retos-para-la-preservacion-de-la-amazonia/?lang=en.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ann Vaughan, “H2Rescue Mission,” Army.mil, April 18, 2024, Accessed July 3, 2025, https://www.army.mil/article/275433/h2rescue_mission.

[23]Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, Department of Defense Climate Adaptation Plan 2021, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Defense, 2021, https://www.sustainability.gov/pdfs/dod-2021-cap.pdf.

[24] Zazala Quist, “Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) – Everything You Need to Know,” Ecochain, February 3, 2024, https://ecochain.com/blog/life-cycle-assessment-lca-guide/.

[25] “Climate and Environment,” BAE Systems, Accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.baesystems.com/en/sustainability/climate-and-environment.

[26] “Sustainable – Using Electrical Energy More Efficiently,” Rheinmetall, May 3, 2020, https://www.rheinmetall.com/en/media/stories/2020/sustainable.

[27] Hanna Lehtimäki, Marjaana Karhu, Juha M. Kotilainen, Rauno Sairinen, Ari Jokilaakso, Ulla Lassi, and Elina Huttunen-Saarivirta, “Sustainability of the Use of Critical Raw Materials in Electric Vehicle Batteries: A Transdisciplinary Review,” Environmental Challenges 16 (August 2024): 100966, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2024.100966.

[28] “Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO),” European Defence Agency, 2025, https://eda.europa.eu/what-we-do/EU-defence-initiatives/permanent-structured-cooperation-(pesco).

[29] European Union, A Strategic Compass for Security and Defence: For a European Union That Protects Its Citizens, Values and Interests and Contributes to International Peace and Security, Brussels: European Union, 2022, https://www.satcen.europa.eu/keydocuments/strategic_compass_en3_web6298d4e4601f2a0001c0f871.pdf.

[30] Duncan Depledge and Tamiris Santos, “The UK Ministry of Defence and the Transition to ‘Low-Carbon Warfare’: A Multilevel Perspective on Military Change,” European Journal of International Security, (December 23, 2024): 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2024.52.

[31] UK Ministry of Defence, “Construction Starts on New Solar Array at Weeton Barracks,” GOV.UK, February 4, 2025, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/construction-starts-on-new-solar-array-at-weeton-barracks.

[32] Marju Kõrts, Climate Change Mitigation in the Armed Forces, Tallinn: International Centre for Defence and Security (ICDS), 2025, https://icds.ee/en/climate-change-mitigation-in-the-armed-forces/.

[33] Luke Clover, Stacy Moore-Callaway, Erik Oksenvaag, John Oliver, and Eric Soler, Envisioning the U.S. Army’s Transition to Electrification and Carbon Neutrality by 2035, Carlisle, PA: U.S. Army War College, April 17, 2024, https://media.defense.gov/2024/Aug/30/2003535966/-1/-1/0/FINAL%20REPORT_%20FOR%20HON%20JACOBSON%20V2%202.PDF.

[34] UK Defence and Security Accelerator, DASA Funded Innovation Gives Old Body Armour a Second Life, GOV.UK, August 29, 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/case-studies/dasa-funded-innovation-gives-old-body-armour-a-second-life.

[35] Agathe Sarfati, Toward an Environmental and Climate-Sensitive Approach to Protection in UN Peacekeeping Operations (New York: International Peace Institute, October 2022), https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2210_Environmental-Protection-Peace-Operations.pdf.

[36] Ibid.

[37] United Nations, “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2015, https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

[38] Robert Strand, “Global Sustainability Frontrunners: Lessons from the Nordics,” California Management Review 66, no. 3 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1177/00081256241234709.

[39] Council of the European Union, Analysis and Research Team (ART), Greening the Armies: Is a Sustainable Approach to National Defence Possible? January 2024, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/67189/art-paper-greening-the-armies.pdf.

[40] Minyeong Kim Han, “Eco-Friendly War: The Paradox of Military Activity amid the Climate Crisis,” Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Asia, November 11, 2024, https://asia.fes.de/news/eco-friendly-war.html.

[41]Duncan Depledge, “Low-Carbon Warfare: Climate Change, Net Zero and Military Operations,” International Affairs 99, no. 2 (February 2023): 423–444, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiad001.

[42] UK Department of Energy & Climate Change, UK Renewable Energy Roadmap, London: Department of Energy & Climate Change, July 2011, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a79e9bae5274a18ba50fb84/2167-uk-renewable-energy-roadmap.pdf.