The expansion of BRICS into BRICS+ with the inclusion of five new members—UAE, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and Indonesia—marks a significant evolution in the bloc’s quest for a more representative multipolar world order. Against this backdrop, Türkiye’s interest in engaging with BRICS+ reflects a broader recalibration of its foreign policy, seeking greater strategic autonomy amid the erosion of Western-centric global structures, such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the European Union (EU). This paper examines Türkiye’s motivations for pursuing closer ties with BRICS+, the opportunities and dilemmas it faces, and the broader implications for global governance.

Türkiye’s strategic rationale aligns with three key dynamics: diversification of economic partnerships beyond traditional Western markets, assertion of geopolitical influence in emerging multilateral frameworks, and positioning itself as a pivotal middle power within the Global South. By aligning with BRICS+, Türkiye aims to expand its access to alternative finance mechanisms like the New Development Bank (NDB), promote trade in local currencies, and enhance cooperation in critical sectors such as infrastructure, energy, and technology. However, Türkiye’s NATO membership, close ties with its traditional allies in the West, and its nuanced relations with India pose constraints to full BRICS accession.

The paper argues that while immediate full membership may be politically complex, Türkiye’s gradual engagement with BRICS+ fits within its evolving multi-vector diplomacy. It explores how Ankara’s ambitions resonate with the broader Global South’s call for more equitable global governance and identifies areas—such as finance, energy transition, and South-South cooperation—where Türkiye could contribute meaningfully to BRICS+ initiatives. Ultimately, Türkiye’s approach to BRICS+ illustrates its pursuit of strategic flexibility amid shifting geopolitical dynamics in the wider Middle East and greater agency in shaping the emerging international order.

Introduction: BRICS+ and the New Multipolar Order

The 17th BRICS Summit, held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on 6-7 July 2025 was significant in many ways. Overshadowed by Middle East tensions, the summit spotlighted Brazil’s leadership in advocating for the interests of the Global South, particularly on climate finance and development (Savarese & Hughes, 2025). Among topics of criticism were the United States’ indiscriminate tariffs and NATO’s decision to hike military spending to 5% of GDP by 2035. However, notable absences from the summit, including presidents of China, Russia, and Egypt, raised questions “over the group’s cohesion and global clout” (Al Jazeera, 2025).

The term “BRIC” was first coined in 2001 by economist James O’Neill, then working at Goldman Sachs, to describe four emerging markets suitable for investment: Brazil, Russia, India, and China. In 2009, South Africa joined the group, transforming it into BRICS. After 15 years, in early 2024, BRICS expanded significantly by admitting four new members—the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Iran, and Ethiopia—broadening its geographic and political reach. This was followed by Indonesia’s accession in 2025, further strengthening the group’s economic weight and strategic relevance, and marking a pivotal shift toward a more ambitious agenda. With these additions, BRICS+ is increasingly positioning itself as an alternative platform to the G7 for the Global South.

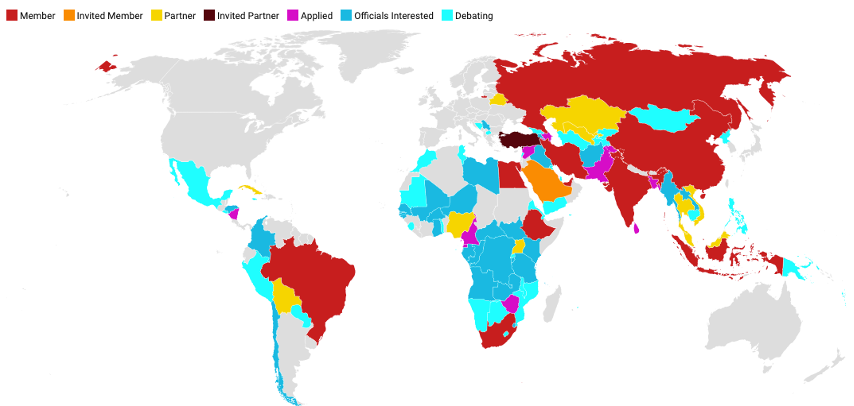

Figure 1: The BRICS Map

Source: BRICS Lab MIT (2025), https://tinyurl.com/yy45nmv7.

BRICS was initially established to challenge the dominance of Western-led institutions such as the Bretton Woods system by addressing shared concerns among emerging economies, ranging from trade imbalances and income inequality to equitable access to financing and the search for alternatives to the U.S. dollar. The BRICS partnership has been built on three main areas of cooperation: political and security collaboration, economic and financial cooperation, and cultural and people-to-people exchanges (Yücel, 2025). Over time, it has evolved into a key advocacy platform for reforming global governance and coordinating issue-based negotiations among developing nations. The Rio summit, the first to include Indonesia, attracted over 20 observer and partner countries—including Türkiye—and was held in the footsteps of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) meeting of the Ministers of Defense in Qingdao, China, just days after the NATO Summit in The Hague, signaling an intentional effort to position BRICS as a counterweight to Western alliances.

The bloc’s growing appeal in the Global South has been accelerated by geopolitical developments, notably the Russia-Ukraine war and intensifying U.S.-China rivalry. Western sanctions on Russia, exclusion from SWIFT, asset seizures, and broader supply chain disruptions have underscored the need for alternative economic platforms. Trade barriers have urged countries to seek alternative sources of critical supplies such as rare earths, semiconductors, and dual-use high-technology products. In this context, BRICS+ has gained traction as a strategic and economic coalition for the Global South. Now comprising ten members, the group accounts for approximately 40% of global GDP (PPP) and almost 45% of the world’s population, surpassing the G7 in demographic weight and rivaling its economic clout. In 2024, BRICS collectively reached 4% GDP growth, while worldwide growth stood at 3.3% (BRICS Brasil, 2025). As it evolves into a US$30 trillion economic powerhouse, BRICS is expected to assume a more assertive role in reshaping the global political, economic, and financial architecture to better reflect multipolar realities.

In this context, Türkiye submitted its application to join BRICS ahead of the summit in Kazan, Russia (2024) with the aim to “bolster its global influence and forge new ties beyond its traditional Western allies” (Hacaoglu & Kozok, 2024). Instead of full membership, however, “Türkiye was offered partner country status” (Reuters, 2024). Türkiye’s bid to join has reportedly been blocked primarily due to India’s objection, rooted in Ankara’s close ties with Pakistan, alongside concerns over its economic instability. India has also entered a bilateral defense cooperation agreement with Türkiye’s archrival Greece, “targeting defense industries, ports, tourism, and potential labor agreements, as part of its broader effort to strengthen its presence in Europe” (Nedos, 2025). Additionally, some member countries such as Russia opposed further enlargement with Türkiye due to “lack of institutional capacity to absorb several new members at once” (A Senior Russian Diplomat, personal communication, October 23, 2024). Still, Türkiye’s bid carries important weight as a symbol of careful balancing by a regional power. As with other multi-aligned middle powers such as Brazil, the UAE, and Pakistan, Türkiye’s approach reflects a strategic hedging posture—leveraging multi-vector partnerships to enhance resilience amid shifting power centers. In this sense, Ankara’s BRICS+ application illustrates not a break from the West but an attempt to expand agency within an evolving multipolar system.

This paper is structured to reflect Türkiye’s evolving calculus toward BRICS+ and assesses its engagement across four analytical pillars. The next section outlines Türkiye’s strategic rationale for aligning with BRICS+, particularly as a middle power, seeking greater agency within an eroding liberal international order. The third section explores the specific opportunities Türkiye envisions within the grouping, ranging from financial and trade mechanisms to South-South cooperation and energy transition partnerships. The fourth section addresses the constraints and dilemmas facing Türkiye’s trajectory, such as tensions with key BRICS+ members, its NATO membership, and unresolved trade imbalances. Finally, the conclusion argues that Türkiye’s approach reflects a strategy of flexible alignment and incremental integration rather than binary alliances. In doing so, the paper aims to contribute to broader debates on how emerging powers are recalibrating their foreign policy to shape a more equitable and pluralistic system of global governance.

Türkiye’s Strategic Rationale for BRICS+ Engagement

Türkiye’s prospective BRICS+ membership represents a strategic maneuver rooted in both economic pragmatism and geopolitical foresight. Ankara’s interest in joining the bloc stems from a desire to diversify its economic partnerships, hedge against volatility in Western alliances, and expand its role within the Global South. As highlighted in the Kazan (16th) and Rio (17th) summits, Türkiye’s presence as an observer and prospective applicant has been welcomed, particularly by Russia and China, which view its accession as enhancing the bloc’s geographic and political weight.

Russia, eager to break its isolation, is open to BRICS+ expansion and supports NATO-member Türkiye’s potential membership, albeit in a staged manner. Moscow’s priority is to enlist closer allies in the “post-Soviet space such as Kazakhstan” and to create a robust economic and political counterweight to Western sanctions by promoting alternative systems outside of SWIFT (A Senior Russian Diplomat, personal communication, October 23, 2024; BRICS Expansion and the Future of World Order, 2025). As the only NATO member that has refrained from imposing sanctions on Russia following the Ukraine war, Türkiye occupies a strategically important position in Moscow’s geopolitical calculus. However, Turkish President Erdoğan aimed to allay suspicion in the West toward the perceived shift in Ankara’s position by saying that “Türkiye’s developing relations with BRICS is by no means an alternative to our existing agreements” (TRT World, 2025).

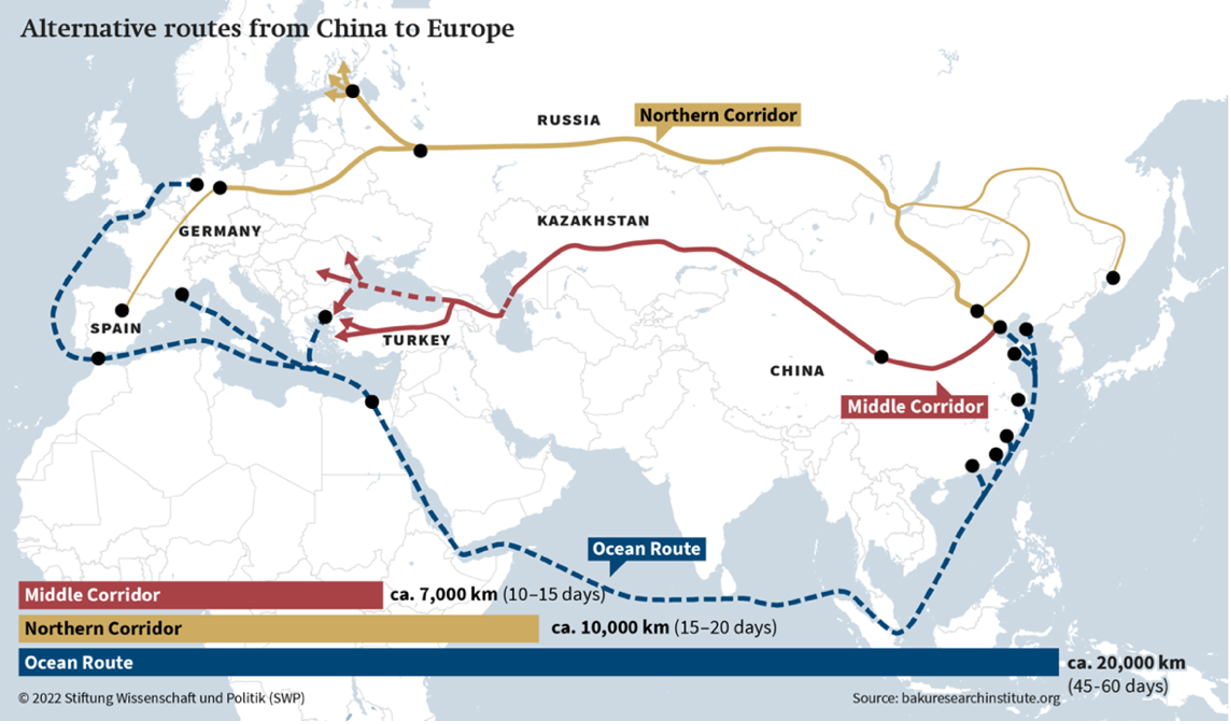

China seeks to legitimize its vision of a “new, non‑Western world order, strengthen its geopolitical leadership among developing nations, and protect its economic interests” by showcasing broad support for multipolarity through BRICS growth (Thibault, 2024). Ongoing geopolitical risks to China’s Belt and Road Initiative’s (BRI) two alternative routes in the north and the south have positioned Türkiye as the most reliable and strategic trade corridor between Europe and Asia. The war in Ukraine has severely disrupted the Northern Corridor, reducing annual container traffic from over 20,000 to 19,000, doubling delivery times from 15–20 days to up to 40, and driving costs up by US$1,000 per container to as high as US$7,500 (Bingöl, 2025). The Maritime Silk Road (Ocean Route) in the Southern Corridor is under challenge by escalating geopolitical risks at sea—such as the “South China Sea disputes, piracy hotspots in the Strait of Malacca, rising instability in the Red Sea corridor”, and tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean—which have threatened the security of vital sea lines of communication, prompting Beijing to pursue alternate overland routes to safeguard its economic lifelines (Oral, 2024).

Freight trains traversing the modern Silk Road via the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR) can complete the journey in as little as 25 days, with Türkiye serving as a central hub along this strategic corridor (Bingöl, 2025). China would benefit from Türkiye’s BRICS+ membership by enhancing synergy between BRI and Türkiye’s Middle Corridor, “strengthening overland connectivity across Central Asia and expanding China’s access to European and Mediterranean markets” through a more secure, diversified, and geopolitically influential transport route (Wenting, 2024). Türkiye’s deep-rooted cultural and linguistic ties with Central Asia allow it to act as a diplomatic bridge within the Global South, especially in engaging Turkic-speaking countries like Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan that are increasingly aligning with BRICS+’ cooperative frameworks. This follows Ankara’s broader strategic efforts in Central Asia, where it has promoted transport and energy connectivity through the Middle Corridor and deepened institutional ties via the Organization of Turkic States (OTS).

Figure 2: Trade Corridors between China and Europe

Source: SWP (2022), https://tinyurl.com/6narwmew, Baku Research Institute (2022), https://tinyurl.com/486w79ja.

Türkiye’s motivation for BRICS+ membership, therefore, is driven more by economic than political reasons. Financially, Türkiye aims to gain access to alternative development financing through the New Development Bank (NDB), reduce transaction costs through local currency settlements, and deepen sectoral cooperation in infrastructure, defense, green energy, and digital innovation. Türkiye’s conservative ruling elite widely view Bretton Woods institutions like the IMF and World Bank as favoring wealthy nations and reinforcing the interests of leading powers within the Western-dominated neoliberal order. At the Rio summit, President Lula da Silva reaffirmed BRICS+’ commitment to democratizing global institutions such as the UN Security Council and the IMF (Savarese & Hughes, 2025), which aligns with Türkiye’s own critiques of Western-dominated structures. Facing growing trade volumes with China and Russia—despite a sizeable trade deficit—Ankara sees BRICS+ as a useful forum to rebalance trade terms, broaden its defense export markets, and create leverage in negotiations with Western partners, including over sanctions and arms procurement.

Politically, some analysts in Türkiye argue that it can leverage BRICS membership as a counterweight to strengthen its hand in dealing with the EU (Polat, 2024). However, BRICS+ offers Türkiye a platform to assert strategic autonomy without abandoning EU aspirations or rupturing its existing ties to NATO. The claim that “by turning to BRICS, Türkiye is abandoning democratic governance” also appears to be an overstatement and lacks sufficient grounding (Demircan, 2024). Ankara’s interest in being a rule-maker, not a rule-taker, fits BRICS+’ reformist ambitions to redefine global governance in more equitable terms, while not necessarily undermining its broader quest for inclusion in Western decision-making circles. Türkiye’s application is not a rejection of the West but a calculated pursuit of multidimensional engagement in an evolving multipolar world.

Opportunities for Türkiye within BRICS+

Türkiye’s prospective inclusion in BRICS+ presents a significant opportunity to recalibrate its geopolitical alignment in a rapidly shifting global order. As the Global South increasingly asserts itself in matters of global governance, Türkiye views BRICS+ as a strategic platform to elevate its voice in international economic and political forums. Like Arab Gulf states such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia, Türkiye’s pursuit of BRICS+ engagement stems from its desire to “reduce dependency on Western institutions while hedging against disruptions in traditional alliances”, especially amid growing U.S.-China rivalry and uncertainty over the West’s future posture toward Eurasia (Çubukçuoğlu et al., 2024).

As a form of pragmatic “minilateralism,” BRICS+ functions less as a unified bloc and more as a flexible coalition of states with shared interests in challenging the asymmetries of the current international system. Its primary agenda, reaffirmed at the Rio summit, centers on reducing the dominance of the U.S. dollar by promoting trade in national currencies and expanding financial sovereignty among member states. This agenda reflects a broader structural shift: over the past 25 years, the U.S. dollar’s share of global reserves has declined from 73% to 56%, mirroring the gradual rebalancing of global power from the Euro-Atlantic toward the Asia-Pacific and emerging economies across the Global South. Türkiye’s membership in BRICS+ could facilitate its participation in the NDB, offering access to non-Western financing mechanisms in local currencies, crucial for insulating its economy from global monetary shocks and U.S. dollar fluctuations. A weaker dollar due to U.S. fiscal and trade policy direction benefits Türkiye by reducing the value of its foreign exchange-denominated debt and “prompting a shift toward assets seen as a hedge against currency volatility”, such as gold or emerging market equities (Nair, 2025).

BRICS+ also offers an alternative forum for conflict transformation, increasingly positioning itself as a diplomatic platform for addressing global crises outside the Western-led multilateral system. Just two days before the BRICS summit in Kazan in 2024, China and India—despite longstanding border tensions—signed a memorandum to “establish joint patrols aimed at easing their disputes”, signaling a cautious thaw in bilateral relations (Al Jazeera, 2024). In a parallel move, China and Brazil led the “Friends of Peace Group” initiative during a high-level meeting of Global South countries and jointly proposed a six-point peace plan to end the war in Ukraine (BRICS Brasil, 2025), further showcasing BRICS+ members’ willingness to act as mediators in protracted global conflicts.

China’s involvement in mediating tensions between Russia and Ukraine, Iran and Saudi Arabia, and potentially India and Pakistan, demonstrates how BRICS+ is evolving into a forum not only for economic coordination but also for de-escalation and dispute resolution among member states and partners. Gulf countries like the UAE are also “actively utilizing their roles in mediation, positive neutrality, and strategic hedging to advance these principles in BRICS+” (BRICS Expansion and the Future of World Order, 2025).

Türkiye—having positioned itself as a facilitator in both the Russia-Ukraine war and regional normalization processes—could bring considerable value to this conflict transformation role within BRICS+, amplifying its own aspirations for middle power mediation and complementing its “Asia Again” initiative (Yeniden Asya Çalıştayı Hitabı, 2019). Moreover, Iran’s active participation in BRICS+—driven by a shared agenda with Russia to counter U.S. influence amid the conflict with Israel—has added urgency to building non-Western coalitions capable of strategic coordination during crises. For Türkiye, whose foreign policy increasingly embraces flexible engagement across rival blocs, this opens up new avenues to contribute to regional stability while pursuing its own interests in a turbulent global environment.

Potential BRICS+ membership could also serve as a strategic lever for Türkiye in its complex relationship with the United States, bolstering Ankara’s negotiating position on critical issues such as the delivery of F-16 fighter jets, the easing of CAATSA-related sanctions, and the return to the F-35 program. As “foreign direct investment (FDI) flows from the West have declined and technology sharing has diminished, Turkish authorities have decided to seek these critical resources for Türkiye’s development objectives from a China-centered ecosystem” (Ülgen, 2025). By signaling its willingness to engage with alternative multilateral frameworks, Türkiye strengthens its geoeconomic flexibility and expands its room for maneuver. The challenge lies in carefully balancing between an assertive U.S. administration intent on containing China and a resurgent Eurasia seeking a greater share of global economic influence and military power.

Constraints and Dilemmas in Türkiye’s BRICS+ Trajectory

Türkiye’s aspiration to join BRICS+ faces structural challenges rooted in the platform’s limited institutional capacity and internal heterogeneity. Unlike the EU or other formalized multilateral frameworks, BRICS+ remains a loosely organized coalition without a standing secretariat, binding legal framework, or unified decision-making body. Its consensus-driven governance model often hampers “swift and decisive action on complex global issues such as climate change, crisis management, or institutional reform” (Çubukçuoğlu, 2024a, 2024b). For Türkiye, which has traditionally leveraged institutional anchoring—whether through NATO or the European Customs Union—this lack of structure may constrain its ability to shape outcomes or safeguard its interests within the bloc.

Geopolitical divergences within BRICS+ also present a dilemma for Türkiye’s strategic balancing act. While Russia and Iran push for a confrontational posture toward the West, other members like India, Brazil, and the UAE maintain more pragmatic ties with the United States and remain cautious about fully aligning with the Sino-Russian axis. Türkiye’s NATO membership and its desire to preserve strong economic ties with the EU and the United States put it in a delicate position. Engaging with BRICS+ without alienating its Western partners requires a nuanced hedging strategy. Complicating Türkiye’s path further, India has reportedly opposed Ankara’s BRICS+ membership , in part due to its deepening strategic partnerships with Greece and Greek Cyprus—states with which Türkiye remains at odds over maritime and sovereignty issues in the Eastern Mediterranean (Ioannidis, 2024; Waldman, 2025), and in part to promote its own intermodal India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC) over Türkiye’s land-based Middle Corridor.

Given that Türkiye’s outreach to BRICS+ is driven more by geo-economic interests—such as financial diversification and trade expansion—than by ideological opposition to the West, it may “temporarily deprioritize its membership ambitions” amid renewed personal diplomacy between Presidents Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Donald Trump”, particularly during a period of heightened U.S.-China tensions (Ülgen, 2025). By contrast, the growing U.S.-China trade war may bolster Chinese investment in Türkiye (The Geopolitics of Trade, n.d.), as firms like BYD shift manufacturing operations there and gain significant market share in the growing Turkish electric vehicle sector.

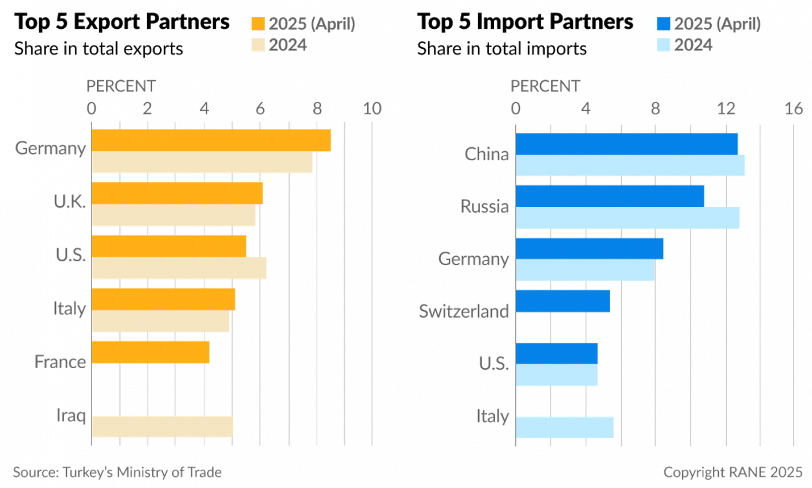

Additionally, Türkiye’s deepening trade relations with BRICS+ economies expose it to risks of economic asymmetry. Its trade deficit with China and Russia alone exceeds US$70 billion—nearly double Türkiye’s current account deficit, raising questions at first sight about the utility of enhanced trade with BRICS+ countries. However, while Türkiye’s trade deficit with China and Russia appears substantial, “much of its imports from China consist of intermediate goods and affordable machinery” that support export-oriented production, while “imports from Russia are largely energy-related”—unlike Western imports, which are predominantly “finished consumer goods”—highlighting the functional and strategic value of Türkiye’s trade with BRICS+ partners (Demircan, 2024). The Prebisch-Singer hypothesis argues that developing countries like Türkiye face deteriorating terms of trade, as the relative prices of their primary goods—such as agricultural and raw materials—consistently decline compared to the manufactured products exported by developed nations (Toye & Toye, 2003). To overcome the unequal exchange between the industrial core and the agrarian periphery, Türkiye’s strategy has focused on sourcing affordable imports to support its manufacturing sector while securing export markets (The Geopolitics of Trade, n.d.), aiming to position itself as an alternative manufacturing hub within BRICS+ for emerging markets in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Africa. This is a long and arduous journey, however, since Türkiye’s largest trading partners are predominantly in the West.

Figure 3: Türkiye’s Largest Trade Partners

Source: Stratfor (2025), https://tinyurl.com/23c736a5.

Still, unless BRICS+ adopts a more proactive agenda that prioritizes technology transfer, FDI, and cooperation in high-value-added sectors, Türkiye may find itself repeating patterns of dependence it has long sought to escape. The absence of clear dispute-resolution mechanisms, harmonized regulatory standards, or coordinated trade facilitation tools within BRICS+ further complicates Türkiye’s potential integration. These structural constraints underscore the importance of realism in Ankara’s BRICS+ ambitions and the need to pursue diversified, rather than exclusive, multilateral engagements.

Conclusion: Strategic Flexibility and Incremental Integration

In an era marked by great power competition, institutional realignment, and fluidity of alliances, Türkiye’s optimal strategy lies in maintaining open channels with all major blocs, broadening its trade partnerships, diversifying sources of financing, and cultivating new markets, particularly for its burgeoning defense industry. As BRICS+ transitions into a more influential platform, Türkiye is well-positioned to leverage its regional leadership and diplomatic agility to contribute meaningfully to the reform of the global political, economic, and financial architecture in pursuit of a more balanced and inclusive international order.

Rather than seeking abrupt alignment or ideological rupture with its Western partners, Türkiye’s engagement with BRICS+ reflects a calibrated strategy of flexible alignment and incremental integration. Ankara’s goal is not to replace one bloc with another, but to expand its agency within an increasingly multipolar world by participating in multiple institutional configurations. This approach enables Türkiye to hedge against geopolitical risks, increase its bargaining leverage in global negotiations, and shape the evolution of non-Western platforms without abandoning its longstanding ties with NATO and the EU.

The path to full BRICS+ membership may remain complex—impeded by geopolitical frictions, institutional limitations, and intra-bloc asymmetries—but Türkiye’s gradual deepening of cooperation through observer status and sectoral partnerships offers a viable roadmap. As a self-styled middle power, Türkiye is not merely reacting to shifts in the global order but actively seeking to shape them. Its BRICS+ engagement thus mirrors a broader foreign policy doctrine that favors agency over alignment, pluralism over polarity, and resilience over rigid dependency.

Ultimately, Türkiye’s BRICS+ trajectory serves as a case study in middle power hedging, wherein states seek to navigate uncertainty not by choosing sides, but by widening their strategic bandwidth. This multi-vector diplomacy allows Türkiye to align with emerging power centers while keeping the door open to reformist dialogue with the West, thereby reinforcing its aspiration to act as a bridge between continents, ideologies, and global governance frameworks.

References

A Senior Russian Diplomat. (2024, October 23). Russia-Türkiye Relations [In Person].

Al Jazeera. (2024, October 21). India says it reached deal with China on army patrols along disputed border. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/10/21/india-says-it-reached-deal-with-china-on-army-patrols-along-disputed-border

Al Jazeera. (2025, July 6). Brazil hosts BRICS summit; Russia’s Putin, China’s Xi skip Rio trip. L. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/7/6/brazil-hosts-brics-summit-russias-putin-chinas-xi-skip-rio-trip

Bingöl, Ö. F. (2025, June 23). Turkish Economy in Brief, Weekly. Türkiye Today. editor@turkiyetoday.com

BRICS Brasil. (2025, May 2). BRICS Brasil 2025. https://brics.br/en/news/brics-gdp-outperforms-global-average-accounts-for-40-of-world-economy

BRICS Expansion and the Future of World Order: Perspectives from Member States, Partners, and Aspirants. (2025, March 31). Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2025/03/brics-expansion-and-the-future-of-world-order-perspectives-from-member-states-partners-and-aspirants?lang=en

Çubukçuoğlu, S. S. (2024a, January 5). The New Horizons for BRICS in 2024. Trends Research & Advisory. https://trendsresearch.org/insight/the-new-horizons-for-brics-in-2024/

Çubukçuoğlu, S. S. (2024b, October 24). Dr. Süha Çubukçuoğlu yazdı: BRICS Zirvesi ve Türkiye’nin Dış Politika Ekseni. Al Ain News Türkçe. https://tr.al-ain.com/article/suha-cubukcuoglu-yazdi-brics-zirvesi-ve-turkiyenin-dis-politika-ekseni

Çubukçuoğlu, S. S., Lyall, N., & Al Midfa, N. (2024, July 28). Perspectives of GCC States Towards BRICS Membership: An Analysis at Macro, Meso, and Micro Levels. Trends Research & Advisory. https://trendsresearch.org/insight/perspectives-of-gcc-states-towards-brics-membership-an-analysis-at-macro-meso-and-micro-levels/

Demircan, N. (2024, September 24). Türkiye’s Eyes on BRICS But Ear to EU. Modern Diplomacy. https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2024/09/24/turkiyes-eyes-on-brics-but-ear-to-eu/

Hacaoglu, S., & Kozok, F. (2024, September 2). Bloomberg.Com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-09-02/turkey-submits-bid-to-join-brics-as-erdogan-pushes-for-new-alliances-beyond-west

Ioannidis, S. (2024, April 4). Greece and India to sign defense cooperation agreement. eKathimerini.Com. https://www.ekathimerini.com/news/1235610/greece-and-india-to-sign-defense-cooperation-agreement/

Nair, D. (2025, July 1). Weaker US dollar dents purchasing power and discretionary spending in Gulf. The National. https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/money/2025/07/01/weak-us-dollar-gulf-spending-investing/

Nedos, V. (2025, May 26). India eyes strategic push in Greece. eKathimerini.Com. https://www.ekathimerini.com/politics/foreign-policy/1270724/india-eyes-strategic-push-in-greece/

Oral, F. (2024). Securing Threatened Maritime Corridors. Journal of Nautical Eye and Strategic Studies, 4(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.58932/MULG0041

Polat, A. C. (2024, September 9). İktidarın siyasi kaygılarla AB’ye karşı BRICS alternatifi yaratma hamlesi tepki çekti: Eksen değişimi riskli. Cumhuriyet. https://www.cumhuriyet.com.tr/ekonomi/iktidarin-siyasi-kaygilarla-abye-karsi-brics-alternatifi-yaratma-2245530

Reuters. (2024, November 14). Turkey was offered partner country status by the BRICS group of nations. https://www.reuters.com/world/brics-offered-turkey-partner-country-status-turkish-trade-minister-says-2024-11-14/

Savarese, M., & Hughes, E. (2025, July 6). BRICS group condemns increase of tariffs in summit overshadowed by Middle East tensions. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/brics-summit-brazil-2025-lula-ee830be326e295fed787032abf43d59a

The Geopolitics of Trade: Turkey’s Export Strategy Hinges on Neutrality | RANE. (n.d.). Stratfor. Retrieved July 2, 2025, from https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/article/geopolitics-trade-turkeys-export-strategy-hinges-neutrality

Thibault, H. (2024, October 22). China pushes for BRICS expansion to legitimize its vision of a new world order. Le Monde.Fr. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2024/10/22/china-pushes-for-brics-expansion-to-legitimize-its-vision-of-a-new-world-order_6730151_4.html

Toye, J. F. J., & Toye, R. (2003). The Origins and Interpretation of the Prebisch-Singer Thesis. History of Political Economy, 35(3), 437–467. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/4/article/46958

TRT World (Director). (2025, July 6). Türkiye maintains close ties with BRICS alliance [YouTube]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNk8NAY7lmM

Ülgen, S. (2025, March 31). BRICS Expansion. Aspirant: Türkiye. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2025/03/brics-expansion-and-the-future-of-world-order-perspectives-from-member-states-partners-and-aspirants?lang=en

Waldman, Dr. S. (2025, June 30). Turkey, BRICS and Erdogan’s Global Aspirations. RUSI. https://www.rusi.orghttps://www.rusi.org

Wenting, X. (2024, July 11). Turkey does not subscribe to anti-China rhetoric, hopes to enhance economic cooperation with Beijing: Ambassador. Global Times. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202407/1315880.shtml

Yeniden Asya Çalıştayı Hitabı. (2019, December 26). T.C. Dışişleri Bakanlığı. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/sayin-bakanimizin-yeniden-asya-calistayi-hitabi-26-12-19.tr.mfa

Yücel, U. T. (2025, July 4). Umur Tugay Yücel | BRICS dışişleri bakanları zirvesi mesajları ve BRICS çalışma grubu toplantıları. Independent Türkçe. https://www.indyturk.com/node/761297/t%C3%BCrki%CC%87yeden-sesler/brics-d%C4%B1%C5%9Fi%C5%9Fleri-bakanlar%C4%B1-zirvesi-mesajlar%C4%B1-ve-brics-%C3%A7al%C4%B1%C5%9Fma-grubu