Abstract

Despite its widespread use as a primary theoretical framework for exploring residents’ attitudes and support towards tourism, and being acclaimed for its significant explanatory potential, Social Exchange Theory (SET) faces scholarly critique for its lack of comprehensiveness and limited ability to fully capture residents’ perspectives. Studies indicate that various factors, notably value orientation, significantly shape residents’ attitudes towards local cultural festivals. This study aims to assess the influence of value orientations towards Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) on attitudes and support for local cultural festivals. By utilizing the Values-Attitudes-Behavior Hierarchy, it seeks to enhance the analysis of residents’ responses within the SET framework, aiming to uncover insights into how these value orientations shape residents’ attitude and support. Analyzing responses from 449 UAE residents using PLS-SEM, findings revealed the significant influence of value orientation on positive impacts attitude, leading to support for local cultural festival development. This research introduces a new framework based on SET to understand the complex factors influencing residents’ support for the development of local cultural festivals, highlighting how their value orientation towards ICH shapes their attitudes and support levels. Discussion on the theoretical and practical implications, limitations of the research, and recommendations for future inquiries are also presented.

Keywords: Intangible cultural heritage; Social Exchange Theory; Cultural festivals; United Arab Emirates

Introduction

Short-term events and festivals are considered a crucial component of cultural tourism and have gained significant attention in destination planning and management (Formica and Uysal, 2016). Local cultural festivals, in particular, have emerged as one of the fastest-growing types of events and have become an essential feature of tourism destinations (Getz, 2008). They play a crucial role in promoting tourism and enhancing regional economies, creating a positive image, expanding tourist seasons, fostering social cohesion within communities and reinforcing the life and pride of local communities (Getz, 2008; Mason and Nassivera, 2013; Chen et al., 2014; Lee, 2014; Felsenstein and Fleischer, 2016). Therefore, local cultural festivals have become an increasingly important aspect of destination planning and management.

To ensure the efficient planning and management of a destination, it is imperative to possess a comprehensive understanding of the attitudes and support of the local community toward local cultural festivals (Sharpley, 2014; Ribeiro et al., 2017). Supporting tourism activities by the local community is crucial for the prosperity of local tourism industries and the long-term sustainability of communities that experience tourism (Sharpley, 2014; Nunkoo and So, 2015). This is especially true for destinations that seek to establish themselves as superlative destinations, such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE), where part of its strategy involves becoming a world-class Events Destination (Sutton, 2016). Therefore, evaluating the local community’s attitudes toward local festivals is essential for tourism planners and managers in the UAE.

Although the potential for local cultural festivals to provide positive economic, social and cultural impacts to the local community appears promising, the extent to which this industry growth can be maintained depends in part on the support of the residents (Sharpley, 2014). Local cultural festivals are vulnerable if the local community observes negative impacts (Jackson, 2008). However, if the positive impacts of local cultural festivals are maintained, they will likely generate and sustain community support (Jackson, 2008). This relationship between the attitudes of the local community toward and support for local cultural festivals can be understood by Social Exchange Theory (Nunkoo and So, 2015), whereby people who benefit from these festivals will also tend to support them. However, according to Li, Wan and Uysal (2019), there are limits to how well Social Exchange Theory accounts for the community’s support for local cultural festivals. How communities think about the development of local cultural festivals is influenced by several factors (Getz, 2010), such as value orientation (Sharpley, 2014). For destinations such as the UAE, which have rich intangible heritage, the community’s value orientations toward Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) likely influence local community’s attitudes toward local cultural festivals.

The main objective of this study is to examine the potential effect of residents’ value orientations toward ICH on their attitudes and support toward the development of local cultural festivals. In particular, the study evaluates the value orientations of the local community in the UAE toward ICH and how such orientations might affect the Social Exchange Theory explanations of local community attitudes and support toward the development of local cultural festivals. The study relied on data from a survey of the local community in the UAE to test the hypothesized relationships.

A Social Exchange Perspective of Community’s Support for Local Cultural Festivals

Scholars have discussed various factors and theories to assess how residents perceive the impacts of tourism and their level of support for tourism development. These factors include emotional solidarity and its factors drawing from Durkheim’s Theory (Woosnam and Aleshinloye, 2013), community participation associated with stakeholder theory (Jaafar, Rasoolimanesh and Ismail, 2017), social disruption theory (Lynn and Stan, 1984), and social representation theory (Pearce, Moscardo and Ross, 1996). However, previous studies lack consensus on the theory and factors with the most significant predictive potential in assessing residents’ support for tourism development. Nevertheless, among the factors that have been examined and recognized are those associated with the widely influential Social Exchange Theory (SET).

SET is a widely used theoretical framework in the field of social psychology that explains how individuals interact with each other in social relationships. According to Ap (1992), SET is “a general sociological theory concerned with understanding the exchange of resources between individuals and groups in an interaction situation”. The theory has been applied to tourism research to understand residents’ attitudes toward tourism development. Previous studies demonstrated that support for tourism development and growth is often higher among residents who personally perceive or experience positive impacts from tourism (Li, Wan and Uysal, 2019; Yeager et al., 2019; Munanura and Kline, 2022).

SET has also been found to be applicable in understanding the residents’ support of events and festival development (Song, Su and Liaoning Li, 2013). However, when looking at the previous studies, the findings and conclusions have varied. For instance, Song, Xing and Chathoth (2015) revealed the significant influence of perceived benefits and costs on individuals’ attitudes and willingness to support and participate in future festivals. Their findings demonstrate a positive correlation between perceived benefits and the level of support for future festivals while perceiving higher costs negatively predicts support. However, even though the Tour de France event had negative impacts, Bull and Lovell (2007) found that Canterbury residents overwhelmingly supported the decision to host it in 2007. These contrasting outcomes emphasize the importance of – and the need for – further research to explore the complexities and contextual factors that shape residents’ attitudes and support for events and festivals. Moreover, there is a concern that individuals’ attitudes might be influenced by factors other than just the exchange relationships between tourism and residents (Sharpley, 2014; Nunkoo and So, 2015). Sharpley (2014), for instance, proposes that individuals’ attitudes toward tourism can be influenced by their value orientations in addition to their direct encounters and experiences with tourism activities.

Value Orientation and Local Cultural Festival Attitudes

Previous studies have argued that several factors underlying the transactional relationship between attitudes toward and support for tourism play an essential role in forming the community’s attitudes toward tourism activities (Sharpley, 2014; Nunkoo and So, 2015; Lai, Pinto and Pintassilgo, 2020). However, according to these studies, the antecedents of tourism attitudes still need to be better understood, and other underlying factors should be explored. One of these factors arguably that could predict a community’s attitudes toward tourism is value orientation (Sharpley, 2014).

Value orientation is the foundation that directs an individual’s behavior; how people evaluate the value of one thing affects their attitude toward that thing or adoption of a particular behavior (Su et al., 2020). The role of value orientation in predicting attitudes is supported by the Values-Attitudes-Behavior Hierarchy (Homer and Kahle, 1988). Homer and Kahle (1988) suggested the cognitive hierarchy model that theorizes a causal relationship from more abstract cognitions (value) to mid-range cognitions (attitude) to a particular behavior. In other words, attitudes toward local cultural festivals are likely to be directly influenced by value orientations that indirectly predict support for local cultural festivals.

Vaske and Donnelly (2007) argued that values transcend objects, situations, and issues; they shape individuals’ lives and are stable over time (Han et al., 2019). In heritage tourism literature, most previous research on value orientations has focused on the experience economy, and value orientations are generally measured by tourists’ willingness to pay (Su et al., 2020). However, tourists were the main focus of these studies (e.g., Alazaizeh et al., 2016). In the context of ICH, it is unclear if local communities have the same value orientations as tourists (Su et al., 2020).

ICH value orientations might include use and non-use (Preservation) values (Klamer, 2013; Alazaizeh et al., 2016; Alazaizeh, Ababneh and Jamaliah, 2020). Use values emphasize the instrumental value of heritage resources; they are derived from the actual use of these resources in tourism activities (e.g., cultural festivals) (Vaske et al., 2001). Meanwhile, non-use values are linked to the benefits from preservation satisfaction of heritage (Lee & Han, 2002). Based on the Values-Attitudes-Behavior Hierarchy approach, both use and non-use values arguably have a potential effect on tourism attitudes (Han et al., 2019). Accordingly, residents’ attitudes toward cultural festivals are assumed to be influenced by their value orientation.

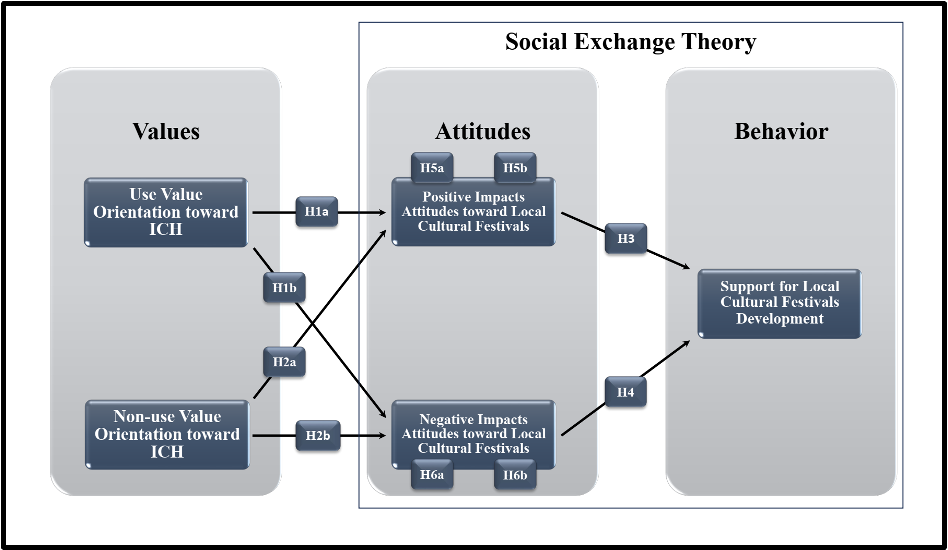

Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

Figure 1 represents the study’s conceptual model. Based on the Values-Attitudes-Behavior Hierarchy, hypotheses 1 and 2 test the potential effect of value orientations on impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals. Hypotheses 3 and 4 examine how impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals might predict the community’s support of local cultural festivals based on the Social Exchange Theory. Hypotheses 5 and 6 examine the potential mediation role of impacts attitudes on the relationship between value orientations and support for local cultural festival development. Thus, the following hypotheses were tested:

H1a: Use value orientation toward ICH is positively related to positive impacts attitudes of local cultural festivals.

H1b: Use value orientation toward ICH is negatively related to negative impacts attitudes of local cultural festivals.

H2a: Non-use value orientation toward ICH is positively related to positive impacts attitudes of local cultural festivals.

H2b: Non-use value orientation toward ICH is negatively related to negative impacts attitudes of local cultural festivals.

H3: Positive impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals positively influence support for local cultural festivals development.

H4: Negative impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals negatively influence support for local cultural festivals development.

H5a: Positive impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals positively mediate the relationship between use value orientation toward ICH and support for local cultural festivals development.

H5b: Positive impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals positively mediate the relationship between non-use value orientation toward ICH and support for local cultural festivals development.

H6a: Negative impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals negatively mediate the relationship between use value orientation toward ICH and support for local cultural festivals development.

H6b: Negative impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals negatively mediate the relationship between non-use value orientation toward ICH and support for local cultural festivals development.

Figure 1. Research conceptual model

Methodology

Survey Development

A quantitative approach was employed to examine the hypothesized relationships in the study. An online self-administrated questionnaire using the SurveyMonkey platform was developed specifically for the study and based on scales used in previous studies. Overall, the final survey contained 37 items on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (7). Value orientations toward ICH were measured by 15 items (Use values 7 items; Non-use values 8 items) adopted from Alazaizeh et al. (2020) and Su et al. (2020). Impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals were measured by 19 items (Positive impacts 9 items; Negative impacts 10 items) adopted from Chen and Chen (2010) and Munanura and Kline (2022). Support for local cultural festival development was measured by 6 items adopted from Chen and Chen (2010), Jaafar et al. (2015) and Ramkissoon and Nunkoo (2011). The survey also included demographic characteristics and general questions.

A consent form was added at the beginning of the questionnaire, including information about the researchers and research institution, the purpose of the study, data confidentiality, anonymity, and security issues. The questionnaire was reviewed by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) at the university were the authors are affiliated and granted a full ethical clearance.

Data Collection

SurveyMonkey Audience service was used to recruit a convenient sample of participants online. SurveyMonkey Audience is a professional online platform with volunteer participants in which responses can be purchased with specific demographic requirements. It recruits survey-takers from millions of people who voluntarily take SurveyMonkey surveys each month. For this research, SurveyMonkey invited participants from a random sample of Audience members who live in the UAE and are 18 years or older. Payment was made for the use of this service based on a requested sample size of 500 participants.

Data Analysis

First, the dataset underwent outlier screening using the SPSS. Of 500 surveys, 449 were deemed valid and included in the final analysis. Data analysis was performed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) with the support of Smart PLS 4.0 software.

The data analysis process involved two main steps. First, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was employed to estimate the construct validity and reliability of items (Byrne, 2013). Second, structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to test the hypothesized relationships between the constructs.

Results

Demographic Profile

Table 1 presents the demographic profile of the respondents. The gender distribution was slightly skewed toward females (55.2%) compared to males. Most respondents fell within the age range of 25 to 44 (61.9%) years old. About three-quarters (76.1%) of the respondents held at least a year of college degree and 53.2% were married. Regarding their residence status, less than half of the respondents live in Abu Dhabi (44.1%), followed by Dubai (33.0%). Almost half of the respondents (49.7%) were citizens, while 47.9% were residents. Lastly, nearly 44 % of the respondents attended one to two festivals the previous year.

Table 1. Demographic profiles of the respondents

| Variable | N | Percentage | |

| GenderMaleFemaleMissingTotal | 1992482449 | 44.355.2.4100 | |

| Age (years)18-2425-3435-4445-54Above 55MissingTotal | 1341641143232449 | 29.836.525.47.1.7.4100 | |

| EducationLess than high schoolHigh school diplomaTwo year college degreeUndergraduate degreePostgraduate degreeMissingTotal | 1887102156842449 | 4.019.422.734.718.70.4100 | |

| Monthly incomeLess than 10,000 AED10,000 – 19,999 AED20,000 – 29,999 AED30,000 – 39,999 AED40,000 – 49,999 AED50,000 – 59,999 AED60,000 AED and aboveMissingTotal | 1548581601923252449 | 34.318.918.013.44.25.15.60.4100 | |

| Marital statusSingleMarriedWidowedDivorcedMissingTotal | 1882391282449 | 41.953.22.71.80.4100 | |

| Residency statusCitizenResidentTourist/VisitorMissingTotal | 22321592449 | 49.747.92.0.4100 | |

| Place of residenceAbu DhabiDubaiSharjahAjmanUmm Al-QuwainFujairahRas Al-KhaimahMissingTotal | 19814851288763449 | 44.133.011.46.21.81.61.30.7100 | |

| Number of visited festival last year0 festival1 – 2 festivals3 – 4 festivals5 festivals and aboveMissingTotal | 56196120752449 | 12.543.726.716.70.4100 |

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of the measurement items utilized in the research model. Given that normality tests can be less reliable for large samples (300 and above), the assessment of normality relied on Skewness and kurtosis values, following the recommendation by Kim (2013); the absolute values of skewness and kurtosis within the range of -2 and 2 are considered acceptable. As presented in Table 2, all measurement items fall within these acceptable levels.

Table 2. Results of the measurement model

| Indicators and factors | Mean (SD) | Skewness (Std Error) | Kurtosis (Std. Error) | Factor loading | a | CR | Rho | AVE |

| F1: Use value orientation toward ICH (USE) | 0.889 | 0.889 | 0.923 | 0.750 | ||||

| USE2: ICH is valuable because it can promote the employment of local peopleUSE3: ICH is valuable because it can generate economic income for the local communityUSE4: ICH is valuable because it is resource with commercial development valueUSE5: ICH is valuable because it is an important economic source | 5.04 (2.03) 4.89 (2.10) 4.96 (2.01) 4.89 (2.03) | -0.838 (0.115) -0.732 (0.115) -0.770 (0.115) -0.727 (0.115) | -0.520 (0.230) -0.762 (0.230) -0.583 (0.230) -0.663 (0.230) | 0.855 0.861 0.900 0.847 | ||||

| F2: Non-use value orientation toward ICH (NON) | 0.896 | 0.897 | 0.928 | 0.762 | ||||

| NON1: ICH is valuable because it is the reflection of the cultural tradition of the UAE communityNON4: ICH is valuable because it can enhance local community importanceNON7: ICH is valuable because it reflects the spirit of UAENON8: ICH is valuable to keep for future generations of humans | 5.15 (2.09) 5.04 (2.14) 5.06 (2.13) 5.18 (2.11) | -0.910 (0.115) -0.848 (0.115) -0.861 (0115) -0.924 (0115) | -0.483 (0.230) -0.688 (0.230) -0.644 (0.230) -0.515 (0.230) | 0.867 0.867 0.869 0.889 | ||||

| F3: Positive impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals (POS) | 0.869 | 0.870 | 0.911 | 0.719 | ||||

| POS4: Shopping opportunities in the community are better because of local cultural festivalsPOS6: Local cultural festivals help to preserve the cultural identity of the communityPOS7: Local cultural festivals lead to more understanding of local heritagePOS8: Local cultural festivals improve infrastructure and facilities | 5.03 (2.06) 5.30 (2.05) 5.25 (2.05) 4.91 (2.02) | -0.835 (0115) -1.015 (0.115) -0.989 (0.115) -0.731 (0.115) | -0.562 (0.230) -0.288 (0.230) -0.314 (0.230) -0.643 (0.230) | 0.846 0.865 0.855 0.825 | ||||

| F4: Negative impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals (NEG) | 0.902 | 0.977 | 0.911 | 0.595 | ||||

| NEG1: Local cultural festivals will create conflict with residentsNEG2: Local cultural festivals cause more traffic congestion and parking problemsNEG3: Local cultural festivals raise local product pricesNEG4: Local cultural festivals increase residents’ living costNEG7: Local cultural festivals misuse the resources of local heritageNEG8: Local cultural festivals cause more litter and pollutionNEG10: Local cultural festivals cause more inconvenience for local residents | 3.30 (2.09) 3.90 (1.97) 3.93 (1.98) 3.74 (1.95) 3.17 (2.11) 3.51 (2.12) 3.32 (2.15) | 0.478 (0.115) -0.028 (0.115) 0.023 (0.115) 0.147 (0.115) 0.528 (0.115) 0.267 (0.115) 0.418 (0.115) | -0.028 (0.115) -1.181 (0.230) -1.126 (0.230) -1.121 (0.230) -1.098 (0.230) -1.297 (0.230) -1.232 (0.230) | 0.753 0.830 0.848 0.744 0.712 0.757 0.750 | ||||

| F5: Support for local cultural festivals development (SUP) | 0.890 | 0.892 | 0.920 | 0.696 | ||||

| SUP1: Overall, I support local cultural festivals development in my citySUP2: I favor implementing new local cultural festivals to attract more touristsSUP3: I would want to see more local cultural festivals in my citySUP5: Tourism authorities should encourage further local cultural festival developmentsSUP6: I frequently visit local cultural festivals | 5.28 (2.13) 5.01 (2.14) 5.36 (2.07) 5.34 (2.06) 4.72 (2.06) | -1.005 (0.115) -0.802 (0.115) -1.070 (0.115) -1.047 (0.115) -0.539 (0.115) | -0.387 (0.230) -0.745 (0.230) -0.202 (0.230) -0.217 (0.230) -0.957 (0.230) | 0.843 0.8210.875 0.858 |

Note: a: Cronbach’s alpha; CR: Composite reliability; AVE: Average Variance Extract

The Measurement Model

CFA first was employed to estimate the relationships of the observed variables with the main constructs. Establishing reflective measurement models requires confirming internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2017). The internal consistency reliability is assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability. As indicated in Table 2, both Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values are above 0.85, signifying high levels of reliability (Hair et al., 2021). The convergent validity was evaluated through outer loading and the average variance extracted (AVE). As presented in Table 2, the convergent validity is met, with all indicators having outer loadings above 0.7, and AVE values surpassing 0.5 (Hair et al., 2017).

The discriminant validity was assessed using Fornell and Larcker’s Criterion (Table 3) (Hair et al., 2017). It is confirmed when the square root of each constructs’ AVE exceeds its correlation with other constructs (Hair et al., 2017). As demonstrated in Table 3, the square root of AVE for each construct is greater than its correlation with other constructs, affirming adequate discriminant validity of all constructs (Fair, et al., 2017).

Table 3. Assessment of discriminant validity using Fornell and Larcker’s Criterion

| Use value orientation | Non-use value orientation | Positive impacts attitudes | Negative impacts attitudes | Support for local cultural festivals | |

| Use value orientation | 0.866 | ||||

| Non-use value orientation | 0.799 | 0.873 | |||

| Positive impacts attitudes | 0.793 | 0.809 | 0.848 | ||

| Negative impacts attitudes | 0.280 | 0.240 | 0.260 | 0.772 | |

| Support for local cultural festivals | 0.788 | 0.787 | 0.779 | 0.227 | 0.834 |

Model fit

The model’s goodness-of-fit was evaluated using Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (RSMR) and the Normed Fit Index (NFI). According to Hu and Bentler (1998, 1999), a satisfactory fit is indicated when SRMR is equal to or less than 0.08 and NFI is equal or larger than 0.85. The results reveal that the SRMR value is 0.069 and the NFI value is 0.845, indicating that the goodness-of-fit measures were within acceptable ranges.

The structural model

According to Fair et al. (2021), the key criteria for assessing the structural model include the path coefficients, effect size (F2), coefficient of determinations (R2), and predictive relevance (Q2). Before conducting the structural model, the model must be examined for potential collinearity issues among constructs to avoid biases. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated to detect the presence of collinearity issues among constructs. The results in table 4 show that the full collinearity of constructs is established, as the VIF values are lower than 5 (Hair et al., 2011).

Table 4. Results of the structural model (bootstrapping)

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Std. Beta | T-value | Decision | VIF | F² | Q² | R² |

| 1a | USEPOS | 0.405 | 7.204* | Supported | 2.760 | 0.207 | 0.709 | 0.714 |

| 1b | USENEG | -0.334 | 4.864* | Supported | 2.760 | 0.023 | 0.069 | 0.079 |

| 2a | NONPOS | 0.486 | 8.206* | Supported | 2.760 | 0.299 | ||

| 2b | NONNEG | 0.045 | 0.652 | Not Supported | 2.760 | 0.001 | ||

| 3 | POSSUP | 0.271 | 4.158* | Supported | 3.508 | 0.073 | 0.684 | 0.711 |

| 4 | NEGSUP | -0.010 | 0.436 | Not Supported | 1.090 | 0.000 | ||

| 5a | USEPOS SUP | 0.110 | 3.874* | Supported | ||||

| 5b | NONPOS SUP | 0.132 | 3.620* | Supported | ||||

| 6a | USENEG SUP | -0.002 | 0.422 | Not Supported | ||||

| 6b | NONNEG SUP | -0.000 | 0.197 | Not Supported |

Note: *= p<0.001

The hypothesized relationships among constructs were tested using structural equation modeling. Bootstrapping, a non-parametric re-sampling technique, was conducted to test the significance of path coefficients (Hair et al., 2017). Table 4 outlines the findings of the hypothesis testing process. Use value orientation toward ICH was found to be positively related to positive impacts attitude toward local cultural festivals (β = 0.405, p < 0.001) and negatively related to negative impacts attitude (β = -0.334, p < 0.001), as hypothesized in H1a and H1b. Non-use value orientation toward ICH was found to be positively related to positive impacts attitude toward local cultural festivals (β = 0.486, p < 0.001), supporting hypothesis H2a. However, the results showed no significant relationship between non-use value orientation and negative impacts attitude (β = 0.045, p > 0.05). Thereby not supporting hypothesis H2b.

Regarding the relationship between attitudes towards the impacts of local cultural festivals and support for their development, the results reveal a significant positive relationship between positive impacts attitude and support for festival development (β = 0.271, p < 0.001), supporting hypothesis H3. Conversely, negative impacts attitude was not found to have a significant influence on support for development of local cultural festivals (β = -0.010, p > 0.05), leading to not supporting hypothesis H4.

In the analysis of mediation effects, hypotheses H5a and H5b were supported. Specifically, the findings show that positive impacts attitude significantly mediates the relationship between use value orientation and support for local cultural festivals development (β = 0.110, p < 0.001), as well as between non-use value orientation and support for local cultural festivals development (β = 0.132, p < 0.001). However, the results indicate that negative impact attitude does not have any significant mediation role between value orientation (both use and non-use) and support for local cultural festivals development (β = -0.002, p < 0.001; β = -0.000, p < 0.001). Consequently, the findings do not support hypotheses H6a and H6b.

It is important to evaluate the effect size (F2) for each path. F2 measures the strength of the relationship between exogenous and endogenous constructs (Cohen, 1988). According to Cohen (1988), the effect size of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 are respectively described as small, medium, and large, whereas the effect size smaller than 0.02 indicates no effect. As shown in Table 4, use value orientation has a strong effect on positive impacts attitude (F2 = 0.207) and a small on negative impacts attitude (F2 = 0.023). In contrast, non-use value orientation has a strong effect on positive impacts attitude (F2 = 0.299), yet it appears to have no effect on negative impacts attitudes (F2 = 0.001). Furthermore, while a positive impacts attitude has a negligible effect on the support for local festivals (F2 = 0.073), a negative impacts attitude does not have an effect on support for the development of local cultural festivals (F2 = 0.000).

The coefficient of determinations (R2) values, as presented in Table 4, indicate the proportion of the endogenous construct variance that can be explained by exogenous constructs (Chin, 1998). Based on Chin (1998), the R2 values of 0.67, 0.33, and 0.19 are regarded as substantial, moderate, and weak. Accordingly, the R2 value of positive impacts attitude can be considered as moderate (R2 = 0.714), substantial for both negative impacts attitude (R2 = 0.079), and support for local cultural festival development (R2 = 0.711).

Finally, the Stone–Geisser index (Q2) value is used to measure the predictive relevance of the research model (Hair et al., 2017). It should be greater than zero to confirm the predictive capability of the research model (Hair et al., 2017). As shown in Table 4, The Q2 value of support for local cultural festival development is 0.684, indicating that the research model has high predictive relevance.

Discussion

Understanding residents’ attitudes and support is crucial for local cultural festivals to be successfully developed and maintained over time. In tourism research, SET is frequently adopted as a primary theoretical framework to examine resident support and is recognized by scholars for its substantial explanatory capacity. Nonetheless, there are concerns raised by some academics regarding the theory’s comprehensiveness in accurately reflecting residents’ perspectives, pointing to its somewhat restricted scope (Hadinejad et al., 2019; Li, Wan and Uysal, 2019). According to Getz (2010), the attitude of residents towards local cultural festivals is shaped by numerous factors, among which value orientation plays a significant role (Sharpley, 2014). Therefore, based on the Values-Attitudes-Behavior Hierarchy approach, this research assesses the value orientations of the UAE residents towards ICH and examines how these orientations might influence the Social Exchange Theory’s explanation of community attitudes and support for these festivals.

The findings reveal a significant correlation between the value orientation of UAE residents toward ICH and their attitudes towards the positive impacts of local cultural festivals. This implies that individuals who place higher use and non-use value on ICH tend to perceive local cultural festivals more favorably, appreciating the benefits these events bring to the community. Indeed, individuals who value ICH, either as a crucial economic resource or as a reflection of the UAE’s cultural traditions, are likely to see the cultural festivals as beneficial, contributing positively to the community by preserving the cultural identity and enhancing the understanding of local heritage. Similarly, Wei, Liu and Park (2021) found that residents who feel a closer personal or communal connection to cultural heritage are more likely to see positive outcomes from ICH–related tourism activities.

A notable aspect of the study is the differing influences of use and non-use value orientations on residents’ perceptions of the negative impacts of local cultural festivals. It was found that residents who place high importance on the instrumental benefits of ICH are likely to perceive or be concerned with fewer potential negative impacts of local cultural festivals. However, residents who appreciate ICH for its intrinsic, non-functional values – such as cultural identity, historical significance, and aesthetic appreciation – do not necessarily correlate this appreciation with a concern about the negative impacts of local cultural festivals. This could be explained through a cognitive bias known as ‘confirmation bias’, where individuals favor perspectives that confirm their pre-existing values (Nickerson, 1998). In this case, the belief in the use of ICH might lead to overlooking any negative impacts associated with local cultural festivals, such as environmental issues, disruption of daily life, or cultural modification. On the other hand, this may be attributed to the fact that despite being perceived as not having an economic exchange value, UAE residents would still not hold negative impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals due to their role in representing and fostering individual and collective identities in a relatively young nation. Furthermore, it could suggest that UAE residents trust that local cultural festival organizers and local authorities will manage these events in a way that minimizes negative impacts, reflecting confidence in the management of cultural events in the region.

The findings corroborate existing critiques of the transactional relationship between residents’ attitudes and their support for local cultural festivals, as conceptualized within the framework of SET (Hadinejad et al., 2019; Li, Wan and Uysal, 2019). Specifically, similar to previous research (Lee, 2013; Nunkoo and Smith, 2013; Nunkoo and So, 2016), the findings suggest that when residents perceive the festivals as having beneficial effects–such as cultural enrichment, community engagement, economic benefits, or tourism development–they are more likely to support the development and continuation of these festivals. However, negative attitudes towards local cultural festivals do not significantly influence the level of support for their development. This finding aligns with the results of prior studies conducted by Gursory, Jurowski and Uysal (2002), Gursoy and Kendall (2006) and Nunkoo and Ramkisson (2012). This means that even if residents have some concerns or perceive certain negative impacts related to the local cultural festivals, these concerns do not affect their overall support for these festivals. In the UAE context, this might reflect a cultural context where the value placed on cultural festivals and their role in preserving and promoting cultural heritage outweighs potential negative attitudes. Furthermore, the positive attitude toward these festivals likely stems from their role in showcasing the UAE’s rich ICH. This is significant in a rapidly globalizing world, where maintaining a distinct cultural identity is both a challenge and a priority. For the UAE residents, therefore, the support for local cultural festivals is not just a matter of preferences; it is a statement of cultural preservation and a response to the globalizing pressures that threaten to homogenize distinct cultural practices.

The results reveal that the way the UAE residents perceive the benefits of local cultural festivals acts as a crucial link between their value orientation and their overall support for these festivals. For instance, if a resident values ICH for its use value or its intrinsic cultural significance (non-use value), this valuation is likely to translate into support for festival development, largely because of their positive perception of the festival’s impacts. This exemplifies how the UAE’s diverse value orientations towards ICH are intricately woven into the societal narrative, leading to a robust support system for these festivals. This deep-rooted cultural reverence for festivals is pivotal in understanding the UAE’s approach to cultural preservation and promotion in the face of rapid modernization and globalization. It underscores the strategic importance of these festivals in maintaining cultural continuity, fostering national pride, and projecting a vibrant cultural image on the world stage. However, while negative impacts of local cultural festivals are perceived, they are not essential in determining the overall support for the festivals, even when residents hold strong value–based connections to the ICH. Within the context of the UAE, most festivals and cultural events are small or medium in size and last for relatively short periods. As such, although they may create minor concerns (e.g., an increase in traffic volume in the areas where the events are held), they do not interfere in a pressing fashion with residents’ routines as, for example, mega-events like the Olympic Games may do. Moreover, since they are regarded as crucial industries to boost and diversify the economy, local festivals in the UAE are parts of a strategic portfolio characterized by rigorous planning and substantial provision of ancillary facilities (e.g., roads, cultural centers, public transport) (Sutton, 2016), an aspect that, in general, may tend to reduce and minimize perceived negative impacts.

Theoretical implications

The findings of this research present several theoretical contributions to the literature on events and cultural festivals. First, as residents’ attitudes and support toward the development of local cultural festivals are shaped by a range of factors (Getz, 2010), this study proposes an alternative framework to understand the dynamics of multiple determinants affecting support for the development of local cultural festivals. Utilizing Social Exchange Theory (SET) as a conceptual basis, this research examines how residents’ value orientation toward Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) influences their level of support for local cultural festival development.

Second, the findings from this study further confirm the value of Social Exchange Theory in explaining residents’ attitudes and their support for local cultural festival development. This is evident as residents show greater support for cultural festival development when they perceive more positive outcomes (Li and Wan, 2013; Li, Wan and Uysal, 2019). Furthermore, the findings reveal that how residents value ICH indirectly affects their willingness to support the development of local cultural festivals. This influence operates through their positive attitude toward the impact that these festivals could have. This suggests that the support for local cultural festivals extends beyond simple preference, signifying a profound dedication to preserving cultural heritage.

Third, the findings reassert the value-attitude-behavior hierarchical model, namely that value orientation toward ICH influences support for local festivals’ development through the mediating role of positive impacts attitudes toward local cultural festivals. Previous research has already established a relationship between value attitude and support for events. In examining reasons for supporting events by local communities in Australia, Gration et al. (2016) found that residents’ support is influenced by different values, including option value (the value of having various options in terms of events), existence value (the value of having events due to their economic and socio-cultural benefits), and bequest value (the value of preserving events for future generations). Our study casts additional light on the nexus between values and behavior by incorporating positive impacts attitude as an additional mediating contributor to consider.

Practical implications

The results of this research have also important practical implications. DMOs and local cultural festival organizers in the UAE can use the findings to make the cultural festivals sector more supportive. Findings indicate that residents’ attitudes towards local cultural festivals are positively related to their support for the development of these events. Thus, organizers of cultural festivals should ensure that developing these festivals results in greater benefits for the local community. It is also important to prioritize keeping the residents aware of the benefits involved. Therefore, the DMOs should implement an internal promotion program to highlight the positive impacts of local cultural festivals on the local population and ensure that these benefits reach the majority of residents.

Furthermore, when planning and promoting local cultural festivals, DMOs and festival organizers should consider the value orientation of residents toward Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH). It is beneficial to adopt a community-centric planning approach that respects and reflects the diverse interests, values, and expectations of the local population. Local cultural festivals in the UAE should offer activities and programs that appeal to the diverse values of residents. For instance, to appeal to residents valuing economic benefits (use value), incorporating elements that promote local businesses, craftsmanship, and tourism is important. However, to meet the expectations of those who appreciate the intrinsic value of cultural heritage (non-use value), focusing on authentic cultural displays, educational workshops, and activities that deepen the understanding of local traditions are essential.

Engaging the community in the planning process is essential to ensure that events reflect the cultural values and expectations of the local population. Such involvement can promote a sense of ownership and pride within the community, resulting in heightened support and diminished resistance to potential negative impacts. For DMOs and local cultural festival organizers in the UAE, some effective practices to consider include showcasing local cultures and artists, local business engagement, involvement in decision-making, community input and feedback facilitation, community development and capacity building (Rogers and Anastasiadou, 2011; Piazzi and Harris, 2016).

Conclusion and future research

In order to provide a supplementary discussion on attitudes and support for local cultural festival development, this study aims to assess residents’ value orientations toward ICH and examine how these orientations might influence the Social Exchange Theory’s explanation of community attitudes and support for local cultural festivals. Employing the assumptions of SET, ten hypotheses were tested using data collected from the residents of the UAE. The Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) approach was used to perform data analysis. The results demonstrated acceptable model fit indices and offered support for six of the ten hypotheses originally proposed. The study results suggest that value orientation toward ICH is a significant predictor of support for local cultural festival development. The results indicate that UAE residents value ICH for both its use and non-use significance; this valuation is likely to translate into support for festival development, largely due to their positive perception of the festivals’ impacts. The findings also indicate that support for SET varies. It was found that residents’ support for the development of cultural festivals increases when they perceive these events as beneficial. However, negative attitudes towards cultural festivals do not significantly influence their support for the festivals’ development.

Despite its theoretical and practical contributions, some limitations of this study are also evident. The foremost limitation is the absence of definitive evidence confirming the representativeness of the study population, as it entirely depends on responses gathered from the SurveyMonkey Audience. The included sample may introduce a bias towards individuals who are more likely to be online. Furthermore, although the study targets all residents in the UAE, it did not sufficiently differentiate between the perspectives of UAE citizens and expatriates. Given the UAE’s diverse population, where expatriates constitute a significant portion, their cultural backgrounds, experiences, and perceptions of local cultural festivals could differ markedly from those of UAE nationals. Future research should focus on conducting a comparative analysis of the attitudes and value orientations towards local cultural festivals between UAE citizens and expatriates. Finally, this research focuses on only the use and non-use value orientations towards ICH. While these two aspects are significant, cultural heritage can encompass a broader spectrum of value orientations, such as educational value, symbolic value, emotional value, or spiritual value. Future research should aim to include a wider range of value orientations towards ICH in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of residents’ attitudes towards local cultural festivals.

References

Alazaizeh, M.M. et al. (2016) ‘Value orientations and heritage tourism management at Petra Archaeological Park, Jordan’, Tourism Management, 57, pp. 149–158. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.05.008.

Alazaizeh, M.M., Ababneh, A. and Jamaliah, M.M. (2020) ‘Preservation vs. use: understanding tourism stakeholders’ value perceptions toward Petra Archaeological Park’, Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 18(3), pp. 252–266. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2019.1628243.i

Ap, J. (1992) ‘Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts’, Annals of Tourism Research, 19(4), pp. 665–690.

Bull, C. and Lovell, J. (2007) ‘The impact of hosting major sporting events on local residents: An analysis of the views and perceptions of canterbury residents in relation to the tour de France 2007’, Journal of Sport and Tourism, 12(3–4). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14775080701736973.

Chen, C.F. and Chen, P.C. (2010) ‘Resident Attitudes toward Heritage Tourism Development’, 12(4), pp. 525–545. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2010.516398.

Chen, P.J. et al. (2014) ‘Can fundraising be fun? An event management study of unique experiences, performance and quality’, Tourism Review, 69(4), pp. 310–328. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-07-2014-0039/FULL/PDF.

Felsenstein, D. and Fleischer, A. (2016) ‘Local Festivals and Tourism Promotion: The Role of Public Assistance and Visitor Expenditure’, 41(4), pp. 385–392. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287503041004007.

Formica, S. and Uysal, M. (2016) ‘Market Segmentation of an International Cultural-Historical Event in Italy’, 36(4), pp. 16–24. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759803600402.

Getz, D. (2008) ‘Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research’, Tourism Management, 29(3), pp. 403–428. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2007.07.017.

Getz, D. (2010) ‘The nature and scope of festival studies’, International Journal of Event Management Research, 5(1), pp. 1–47. Available at: www.ijemr.org.

Gursoy, D., Jurowski, C. and Uysal, M. (2002) ‘Resident attitudes: A Structural Modeling Approach’, Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), pp. 79–105. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00028-7.

Gursoy, D. and Kendall, K.W. (2006) ‘Hosting mega events: Modeling Locals’ Support’, Annals of Tourism Research, 33(3), pp. 603–623. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ANNALS.2006.01.005.

Hadinejad, A. et al. (2019) ‘Residents’ attitudes to tourism: a review’, Tourism Review, 74(2), pp. 157–172. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-01-2018-0003/FULL/XML.

Han, H. et al. (2019) ‘Word-of-mouth, buying, and sacrifice intentions for eco-cruises: Exploring the function of norm activation and value-attitude-behavior’, Tourism Management, 70, pp. 430–443. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2018.09.006.

Homer, P.M. and Kahle, L.R. (1988) ‘A Structural Equation Test of the Value-Attitude-Behavior Hierarchy’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(4), pp. 638–646. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.4.638.

Jaafar, M., Noor, S.M. and Rasoolimanesh, S.M. (2015) ‘Perception of young local residents toward sustainable conservation programmes: A case study of the Lenggong World Cultural Heritage Site’, Tourism Management, 48, pp. 154–163. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2014.10.018.

Jaafar, M., Rasoolimanesh, S.M. and Ismail, S. (2017) ‘Perceived sociocultural impacts of tourism and community participation: A case study of Langkawi Island’, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 17(2), pp. 123–134. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358415610373.

Jackson, L.A. (2008) ‘Residents’ perceptions of the impacts of special event tourism’, Journal of Place Management and Development, 1(3), pp. 240–255. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/17538330810911244/FULL/PDF.

Klamer, A. (2013) ‘The values of cultural heritage’, in I. Rizzo and A. Mignosa (eds) Handbook on the economics of cultural heritage. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, pp. 421–437.

Lai, H.K., Pinto, P. and Pintassilgo, P. (2020) ‘Quality of Life and Emotional Solidarity in Residents’ Attitudes toward Tourists: The Case of Macau:’, 60(5), pp. 1123–1139. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520918016.

Lee, C. and Han, S. (2002) ‘Estimating the use and preservation values of national parks ’ tourism resources using a contingent valuation method’, Tourism Management, 23, pp. 531–540.

Lee, J. (Jiyeon) (2014) ‘Visitors’ Emotional Responses to the Festival Environment’, 31(1), pp. 114–131. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.861726.

Lee, T.H. (2013) ‘Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development’, Tourism Management, 34, pp. 37–46. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2012.03.007.

Li, X. and Wan, Y.K.P. (2013) ‘Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development in macao: A path model’, Tourism Analysis, 18(4), pp. 443–455. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3727/108354213X13736372326073.

Li, X., Wan, Y.K.P. and Uysal, M. (2019) ‘Is QOL a better predictor of support for festival development? A social-cultural perspective’, 23(8), pp. 990–1003. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1577807.

Lynn, E.J. and Stan, A. (1984) ‘Boomtowns and Social Disruption’, Rural Sociology, 49(2), pp. 230–246.

Mason, M.C. and Nassivera, F. (2013) ‘A Conceptualization of the Relationships Between Quality, Satisfaction, Behavioral Intention, and Awareness of a Festival’, 22(2), pp. 162–182. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2011.643449.

Munanura, I.E. and Kline, J.D. (2022) ‘Residents’ Support for Tourism: The Role of Tourism Impact Attitudes, Forest Value Orientations, and Quality of Life in Oregon, United States’, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2021.2012713.

Nickerson, R.S. (1998) ‘Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises’, 2(2), pp. 175–220. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175.

Nunkoo, R. and Ramkissoon, H. (2012) ‘Power, trust, social exchange and community support’, Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), pp. 997–1023. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ANNALS.2011.11.017.

Nunkoo, R. and Smith, S.L.J. (2013) ‘Political economy of tourism: Trust in government actors, political support, and their determinants’, Tourism Management, 36, pp. 120–132. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2012.11.018.

Nunkoo, R. and So, K.K.F. (2015) ‘Residents’ Support for Tourism: Testing Alternative Structural Models’, 55(7), pp. 847–861. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515592972.

Nunkoo, R. and So, K.K.F. (2016) ‘Residents’ Support for Tourism: Testing Alternative Structural Models’, Journal of Travel Research, 55(7), pp. 847–861. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515592972/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_0047287515592972-FIG2.JPEG.

Pearce, P.L., Moscardo, G. and Ross, G.F. (1996) Tourism Community Relationship. Oxford: Pergamon.

Piazzi, F. and Harris, R. (2016) ‘Community Engagement and Public Events: The Case of Australian Folk Festivals’, Event Management, 20(3), pp. 395–408. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3727/152599516X14682560744794.

Ramkissoon, H. and Nunkoo, R. (2011) ‘City Image and Perceived Tourism Impact: Evidence from Port Louis, Mauritius’, 12(2), pp. 123–143. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2011.564493.

Ribeiro, M.A. et al. (2017) ‘Residents’ attitudes and the adoption of pro-tourism behaviours: The case of developing island countries’, Tourism Management, 61, pp. 523–537. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2017.03.004.

Rogers, P. and Anastasiadou, C. (2011) ‘Community Involvement in Festivals: Exploring Ways of Increasing Local Participation’, Event Management, 15(4), pp. 387–399. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3727/152599511X13175676722681.

Sharpley, R. (2014) ‘Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research’, Tourism Management, 42, pp. 37–49. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2013.10.007.

Song, Z., Su, X. and Liaoning Li (2013) ‘The Indirect Effects of Destination Image on Destination Loyalty Intention Through Tourist Satisfaction and Perceived Value: The Bootstrap Approach’, Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 30(4), pp. 386–409. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.784157.

Song, Z., Xing, L. and Chathoth, P.K. (2015) ‘The effects of festival impacts on support intentions based on residents’ ratings of festival performance and satisfaction: a new integrative approach’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.957209.

Su, X. et al. (2020) ‘How is Intangible Cultural Heritage Valued in the Eyes of Inheritors? Scale Development and Validation’:, https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348020914691, 44(5), pp. 806–834. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348020914691.

Sutton, J. (2016) ‘From desert to destination: conceptual insights into the growth of events tourism in the United Arab Emirates’, https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2016.1191765, 27(3), pp. 352–366. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2016.1191765.

Vaske, J. and Donnelly, M. (2007) Perceived Conflict with Off Leash Dogs at Boulder Open Space and Mountain Parks Sponsored by the City of Boulder Open Space and Mountain Parks and conducted by. Fort Collins.

Vaske, J.J. et al. (2001) ‘Demographic Influences on Environmental Value Orientations and Normative Beliefs About National Forest Management’, Society & Natural Resources, 14(9), pp. 761–776. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/089419201753210585.

Wei, Y., Liu, H. and Park, K.S. (2021) ‘Examining the Structural Relationships among Heritage Proximity, Perceived Impacts, Attitude and Residents’ Support in Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism’, Sustainability 2021, 13(15), p. 8358. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/SU13158358.

Woosnam, K.M. and Aleshinloye, K.D. (2013) ‘Can Tourists Experience Emotional Solidarity with Residents? Testing Durkheim’s Model from a New Perspective’, Journal of Travel Research, 52(4), pp. 494–505. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512467701.

Yeager, E.P. et al. (2019) ‘Modeling Residents’ Attitudes toward Short-term Vacation Rentals:’, 59(6), pp. 955–974. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519870255.