Introduction

Forming the Western flank of the vast Indo-Pacific region, the Western Indian Ocean is rapidly emerging as a strategic theatre in its own right. Beyond its evident energy and resource potential, this vast oceanic region is gaining in strategic importance on account of heightened geopolitical contestation. In its waters and strewn-out archipelagos, and among the states lining the Western Indian Ocean’s edges, major world powers with global reach are eyeing each other’s activities, including the establishment of military facilities in the area. Such developments possess a local dimension. African coastal states abutting the Indian Ocean and tiny island states alike are leveraging their location, as well as resource potential, to extract benefits from these interested parties.

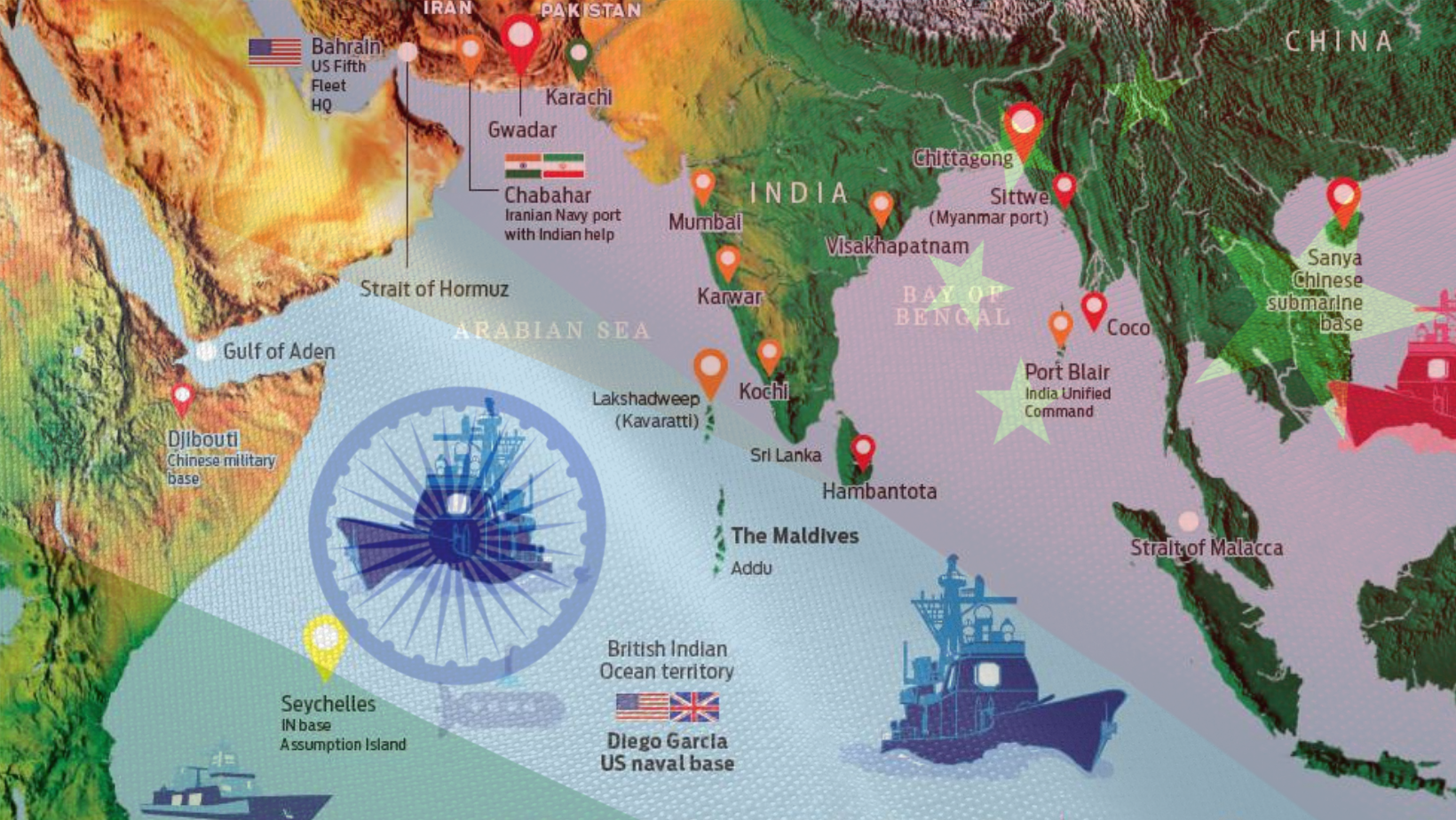

A surprising range of regional and extra-regional powers have shown their interest in this maritime zone. Indeed, military forces from such diverse countries as France, China, Japan, Britain, Germany, and South Korea enjoy some sort of permanent or semi-permanent presence in the Western Indian Ocean. These powers were more recently joined by Russia. This heightened activity has pressed New Delhi to ramp up its presence in what it sees as an area falling within its natural sphere of influence. To be sure, the Indian Navy—alongside the United States from its indispensable military installation in Diego Garcia—has been the major player in this region for some time. India’s renewed drive to establish a stronger basing presence in the Western Indian Ocean, however, is largely a reaction to the real and perceived military and political maneuverings by Beijing in what Indian strategists consider the rising power’s own backyard.

Chinese base chasing

Since 2017, China has made no bones about its intention to build overseas military facilities in a bid to project influence as well as safeguard its economic interests and citizenry. World-wide, the U.S. and its Quad partners, of which India is perhaps the lynchpin,[1] find themselves maneuvering to try to block China from projecting its military power from new overseas bases, from Cambodia to the Atlantic coast of West Africa. Headlines were awash with rumors that Beijing was building a military installation in the UAE, a key U.S. partner in the Middle East. More recently, classified American intelligence reports that reached the public domain suggest China intends to establish its first permanent military presence on the Atlantic Ocean in the tiny Central African country of Equatorial Guinea.[2]

Observers have been swift to see China’s basing ambitions in the Western Indian Ocean as being driven by the need to have a military component complementing the economic and political aims of its so-called One Belt, One Road (OBOR) plan. In line with this thinking, it was little surprise that Beijing formally opened its first overseas military base in 2017 in Djibouti. The former French colony looks onto the Bab-el-Mandeb strait, a strategic chokepoint for shipping traffic transiting the Suez Canal. It is more than a symbolic or low-key facility, like some of Beijing’s other titular “bases”. The Chinese facility at Djibouti has a pier capable of docking an aircraft carrier and nuclear submarines. Upgrades to the base give China potential inroads into the wider Indian Ocean.[3] Reflecting growing U.S. suspicions of Chinese basing ambitions in the Western Indian Ocean, a Pentagon report issued to Congress in 2021 concluded that China “has likely considered” bases in Kenya, Seychelles, and Tanzania.[4] One difficulty analysts have in determining China’s basing strategy is the way Beijing mixes the building of civilian infrastructure with possible defense uses and other security benefits. Chinese state-owned companies have built 100 commercial ports around Africa in the past two decades, according to Chinese government data.[5]

India’s Indian Ocean pivot

To be clear, India has been pushing for deeper security ties with Indian Ocean nations to its south and southwest long before China’s establishment of a base in Djibouti. India’s reemphasis in the security of the Western Indian Ocean is the consequence of the massive movement of geopolitical tectonic plates underway. Geopolitical realities are never static and shifts in the balance of power challenge old assumptions; countries routinely adjust their strategies and find partners appropriate for responding to the evolving structure of the strategic environment. Of the four Quad members, India is the only country which defines the entire Indian Ocean as its area of priority.[6] When it comes to the Western Indian Ocean, India is simply indispensable in fulfilling the Indo-Pacific strategies of the Quad partners and their like-minded allies attempting to uphold what they describe as the global rules-based order.[7] There is little doubt that China’s seemingly military interest in the Western Indian Ocean has accelerated and intensified India’s already-underway pivot.

New Delhi’s foci for its overseas military involvement have been Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Mauritius and the Seychelles. Indeed, the small, remote Mauritian island of North Agalega, located in the south-western Indian Ocean, 1,122 kilometers north of Mauritius, is currently a hive of construction activity – both Indian and Chinese.[8] India, for instance, sought access to the islands in 2015 to develop as an air and naval staging point for surveillance of the south-west Indian Ocean.[9] India has long had a close security relationship with Mauritius, anchoring its prominent role in the south-west Indian Ocean. The relationship is bolstered by ethnic ties and a shared Hindu religion with many Mauritians. This has led commentators to describe Mauritius as the “Little India” of the south-west Indian Ocean—evidenced in part by Indian funding of major infrastructure projects, and provision of lines of credit. This simplistic explanation, however, tends to rub many Mauritians up the wrong way and leaders in Port Louis regularly engage China, Japan, and other powers to balance an omnipresent and, at times, overweening India. Geopolitical wrangling, nevertheless, is even more pronounced in the paradisiac Seychelles archipelago.

Presumptions about Assumption Island

India has sought to further develop its military access to the south-west Indian Ocean and Mozambique Channel by building a new naval and air facility on Seychelles’ remote Assumption Island. Indeed, in 2015, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi even signed an agreement with his Seychellois counterpart to develop Assumption Island for military use.[10] Modi’s deal —in India’s eyes— was necessitated by China’s previous actions on the island. These date to 2011, when a Chinese defense minister visited and the Seychellois leadership offered China port access to resupply Chinese navy vessels enroute to anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden. This led New Delhi to propose closer naval collaboration and offer to build a coastguard facility and airstrip on Assumption Island. The deal, however, generated considerable political opposition in the Seychelles. A revised deal was signed in 2018, but the recently elected Seychelles president, Wavel Ramkalawan, recently shelved the project, purportedly over sovereignty and environmental concerns. Ramkalawan found himself in an awkward diplomatic spot as a result of the stances he adopted during his years in opposition. In 2015, for example, he campaigned against India’s plans for Assumption Island, and forced them to be canceled.

The strategic significance of the island for great powers like China and India should not be ignored. According to Dennis Hardy, Emeritus Professor and former Vice Chancellor of the University of Seychelles, “Assumption is not just about an airstrip and naval jetty.” Leaked reports, he claims, included plans for a garrison of up to 500 military personnel. “It is extraordinary that a small island state with a population below 100,000 can have this attraction to a world power,” Hardy told press sources.[11] China has certainly taken steps to counter India’s moves by deepening its own defense and security co-operation with Seychelles. It has trained the military units of Seychelles’ armed forces as well as gifting two light aircraft and two naval ships. In addition, Beijing has dispatched senior figures from the Chinese armed forces and the Central Military Commission to visit the islands. Displaying its financial muscle, China had financed the building of Seychelles’ parliament building as well.

As the geopolitics in the Indian Ocean heats up, the importance of smaller yet geostrategically located island nations like the Seychelles is growing—and its politicians know it. Seychelles has been playing the geopolitical game quite smartly and has managed to keep competing powers on their toes.

Scrimmage in the Maldives

Located southwest of India’s west coast, the Maldives archipelago is known for its coral atolls and white sand beaches. The capital, Malé, is in the grips of a great power tug-of-war that once again pits its traditional partner, India, against a newcomer, China. Using its economic strength, China has attempted to gain access to strategic territory in the archipelago for the ostensible purposes of developing much-needed infrastructure in the country. Generous loans from Beijing finance these dual-use projects. As in the Seychelles, China used a state visit by President Xi Jinping in 2014 to establish closer relations with then-President Abdulla Yameen. In 2016, a Chinese company received a 50-year lease to develop the tiny island of Feydhoo Finolhu, located just three nautical miles from the Maldivian capital, Malé. Fehdhoo Finolhu is not just a tourist gem, but strategically located to allow surveillance of nearby shipping channels as well as traffic at the capital’s main airport, which China is expanding and upgrading with funding from the Export Import Bank of China.[12] Building on the small island also attracted local opposition, even though the work done thus far shows tourist accommodations and a small dock for tour boats. Nevertheless, Yameen’s political nemesis, former president Mohamed Nasheed, asked for India’s assistance to counter what some Maldivians perceived as a Chinese takeover. Yameen countered this move by calling elections. Surprisingly, he was thrown out of office by the opposition leader, Ibrahim Mohamed Solih, who quickly distanced himself from China and drew close to India, which announced a $500 million package to fund the Maldives’s largest infrastructure project to connect Malé to three nearby islands.[13]

String of ports or global entrepot connectors?

Rounding out what New Delhi increasingly sees as Chinese attempts to surround it with bases are the ports in Kenya, Oman and Pakistan. Operations at the port of Mombasa on Kenya’s Indian Ocean coast, and the main port in East Africa, may be assumed by China should a Kenya default on its $7 billion loan for a railroad built by China.[14] According to a leaked document, Mombasa may serve as collateral for the railroad, which is not profitable. While this would certainly give China more leverage in Kenya, India sees the possibility that Chinese naval vessels may be able to operate from the port. Given the Chinese presence in Djibouti and possibly Mombasa, India’s fears of the Indian Ocean becoming a Chinese lake are compounded by China’s building of ports in Duqm (Oman) and Gwadar (Pakistan). Both are earmarked as blue water ports and should the Chinese navy continue to grow at its current rate, a permanent Chinese naval presence may be seen to India’s west.

Conclusion

Small states often bear the brunt of great power politicking. According to Mohan Malik, “more often than not… the attempts by small states to extract benefits by playing one great power off against another boomerang as they fall prey to intervention by external forces aimed at influencing and shaping domestic political outcomes in places like the Seychelles and Mauritius to their advantage.”[15] Certainly, the internal politics of these small, Indian Ocean island states has been thrown into flux by the arrival of China as an alternative partner to India. Yet, have distributions of power really shifted in China’s favor as opposed to India’s and its natural geopolitical advantage of being the Indian Ocean state? The fact remains that China’s economic presence has grown exponentially across the region on account of its all-directional Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), but its military footprint, while slightly larger on account of its bases in Djibouti, remains underdeveloped. This is on account of its national interests, which means that the majority of its newly minted blue water navy remains in waters near China’s east coast, and also because it currently lacks the material capabilities to deploy significant numbers of its surface fleet to the Indian Ocean. In addition, none of the states have explicitly agreed to a Chinese naval presence at their ports, bar Djibouti, which also has deals to base American, Japanese, French and other militaries on its soil. Indian naval power, together with America’s might via its bases at Djibouti, Bahrain, Qatar, Diego Garcia, Singapore, and Australia, remain the major Indian Ocean naval powers for the time being. That China may seek to upend this in the future remains to be seen.

References

[1] Brendon J. Cannon and Ash Rossiter, “Locating the Quad: Informality, Institutional Flexibility, and Future Alignment in the Indo-Pacific,” International Politics (published online, March 2022).

[2] Michael M. Phillips, “China Seeks First Military Base on Africa’s West Coast, U.S. Intelligence Finds,” Washington Post, 5 December 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-seeks-first-military-base-on-africas-atlantic-coast-u-s-intelligence-finds-11638726327.

[3] Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury, “China Widens Presence in Indian Ocean through Massive Inroads in Djibouti,” Economic Times, 1 October 2021, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/china-widens-presence-in-indian-ocean-through-massive-inroads-in-djibouti/articleshow/86676234.cms?from=mdr.

[4] Ryo Nakamura, Ken Moriyasu and Tsukasa Hadano, “China Has Multiple Military Basing Options in Africa, Analysts Say,” Nikkei Asia, 22 December 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Indo-Pacific/China-has-multiple-military-basing-options-in-Africa-analysts-say.

[5] Michael M. Phillips, “China Seeks First Military Base on Africa’s West Coast, U.S. Intelligence Finds,” Washington Post, 5 December 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-seeks-first-military-base-on-africas-atlantic-coast-u-s-intelligence-finds-11638726327.

[6] Shannon Tiezzi, “Darshana M. Baruah on Indian Ocean Geopolitics,” The Diplomat, 1 June 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/05/darshana-m-baruah-on-indian-ocean-geopolitics/.

[7] Harsh V. Pant and Shashank Matoo, “The Rise and Rise of the ‘Quad’: Setting an Agenda for India,” Observer Research Foundation, Special Report, no. 161, September 2021, https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-rise-and-rise-of-the-quad-setting-an-agenda-for-india/.

[8] Mohan Malik, “Small Island States’ Security in the Indo-Pacific,” in Brendon J. Cannon and Kei Hakata, Indo-Pacific Strategies: Navigating Geopolitics at the Dawn of a New Age, (171-172), Oxon: Routledge, 2021.

[9] Samuel Bashfield, “Agalega: A Glimpse of India’s Remote Island Military Base,” The Interpreter (Lowy Institute), 2 March 2021, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/agalega-glimpse-india-s-remote-island-military-base.

[10] Dipanjan Rou Chaudhury, “India and Seychelles Agree on Naval Base at Assumption Island,” Economic Times, 13 June 2018, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/india-and-seychelles-agree-on-naval-base-at-assumption-island/articleshow/64731817.cms?from=mdr.

[11] Marwaan Makan-Marker, “Seychelles in Crosshairs of India’s Maritime Security Axis,” Nikkei Asia, 11 December 2020, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Indo-Pacific/Seychelles-in-crosshairs-of-India-s-maritime-security-axis.

[12] AMTI, “Chinese Investment in the Maldives: Appraising the String of Pearls,” CSIS, 4 September 2020, https://amti.csis.org/chinese-investment-in-the-maldives-appraising-the-string-of-pearls/.

[13] Mohan Malik, “Small Island States’ Security in the Indo-Pacific,” in Brendon J. Cannon and Kei Hakata, Indo-Pacific Strategies: Navigating Geopolitics at the Dawn of a New Age, (171-172: 171), Oxon: Routledge, 2021.

[14] Brendon J. Cannon, “Influence and Power in the Western Indo-Pacific: Lessons from Eastern Africa,” in Brendon J. Cannon and Kei Hakata, Indo-Pacific Strategies: Navigating Geopolitics at the Dawn of a New Age, (216-232: 223-227), Oxon: Routledge, 2021.

[15] Mohan Malik, “Small Island States’ Security in the Indo-Pacific,” in Brendon J. Cannon and Kei Hakata, Indo-Pacific Strategies: Navigating Geopolitics at the Dawn of a New Age, (171-172: 171), Oxon: Routledge, 2021.