The conflict in the South China Sea, one of the world’s most vital waterways, has escalated to a dangerous level recently, with rising tensions between China and the Philippines over their competing maritime claims. In August 2024, a Chinese naval vessel rammed a Philippine ship during a routine resupply mission to Sabina Shoal, an island the Philippines fears China might seize, as the latter claims sovereignty over about 90% of the South China Sea. The situation worsened when China demanded the withdrawal of a Philippine Coast Guard vessel anchored at the shoal, threatening to use force. The vessel was eventually withdrawn, although Manila announced plans to replace it with another. The United States condemned China’s “dangerous and destabilizing conduct” in the region and expressed its readiness to escort Philippine resupply ships in the South China Sea and activate the mutual defense treaty with the Philippines.[1]

While Chinese naval exercises were underway around Scarborough Shoal, which has been under China’s control since 2012, the Philippines, the United States, Canada, and Australia conducted joint naval and air exercises. Following that, the Philippines engaged in bilateral naval exercises with the United States in the South China Sea (July-August 2024).[2]

This raises the issue of U.S. intervention in the South China Sea conflict, which is sometimes referred to as “the most dangerous conflict no one is talking about,”[3] which could potentially lead to a confrontation with China. Until recently, the Philippines had been using double strategic hedging toward China and the U.S. However, the election of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. as President of the Philippines in June 2022 marked a critical turning point in the country’s relations with both nations. The new president began strengthening the alliance with the U.S., engaging more closely with the U.S.-led network of alliances in the Indo-Pacific region, and pursuing an assertive policy toward China. It seems that the Philippines has abandoned its strategic hedging policy in favor of pursuing a balancing strategy toward China.

This paper examines how and why the foreign policy of the Philippines toward China and the U.S. has changed. In doing so, the paper is divided into three sections. The first section shows the distinction between hedging and balancing strategies. The second section examines the variables that explain the shifts in Philippine policy toward China and the U.S. Finally, the third section tackles the main manifestations of these policy shifts.

The distinction between hedging and balancing strategies

Strategic hedging entails that a “hedging” state engages in various interactions with the powerful threatening state (PTS) to mitigate risks or avoid entering disproportionate conflicts. Simultaneously, the “hedging” state prepares for any potential confrontation with the PTS by developing its military and economic capabilities, and/or engaging in alliances with powers that rival the PTS.[4]

The main threat to the hedging state is not only a possible confrontation with the PTS but may also take the form of an economic blockade, diplomatic boycott, or even armed clashes. Strategic hedging works to minimize these threats by enhancing the military capabilities of the hedging state while avoiding engaging in hard balancing and developing economic capacities through various means, such as diversifying energy sources, increasing the number of trade partners, and acquiring advanced technology.[5] It is noted that the short-term costs accepted by the hedging state to enhance its own capabilities are far less burdensome than the potential costs of a sudden conflict with the PTS.

Therefore, hedging is defined as an insurance-seeking behavior under high-stakes and high-uncertainty conditions that aims at mitigating and offsetting risks while maximizing returns via three approaches: active neutrality, inclusive diversification and prudent fallback cultivation. Accordingly, hedging is conceived of not only as a “middle” position between the competing powers but also as an “opposite” position, where two or more mutually counteractive measures are pursued to offset risks of uncertainties and cultivate fallback options.[6]

The balancing strategy, or balance of power, aims to maintain the national security of a state by engaging in alliances (external balancing) and developing military capabilities (internal balancing) to counter the PTS.[7] What is meant here is positive balancing, which refers to improving military and non-military capabilities by pursuing internal or external balancing strategies, whether military or non-military.

Military internal balancing strategies include intensive development of military capabilities, increased military spending, advancements in military technology, and increasing the size of the armed forces and import of weapons. Non-military internal balancing strategies involve improving economic capabilities, maintaining a strategic reserve of essential goods, developing infrastructure, and enhancing the quality of the media.

Military external balancing strategies include military alliances, joint defense agreements, arms exports, the transfer of military technology to allies, and joint military drills. Non-military external balancing strategies include providing economic aid to allies, increasing direct foreign investment in their countries, expanding trade exchange with them, and fostering technological cooperation and training programs with them.[8]

The distinction between balancing and hedging strategies can be drawn based on their principal drivers, enabling conditions, the nature of alliances, and the key tools employed in their execution. The principal driver behind hedging is the quest for insurance, which means minimizing and offsetting risks and cultivating fallback options. In contrast, the principal driver behind balancing is the quest for security, which involves counterbalancing the PTS. The enabling conditions for adopting a hedging strategy arise from uncertainty in the existing structural conditions (diffuse threats and uncertain support from allies), whereas the enabling conditions for adopting a balancing strategy stem from a state’s certainty about the presence of a major threat and the support of its principal ally or allies.

With regard to the nature of alliances, a hedging state avoids aligning itself with any particular party, keeps an equal distance from competing powers and refrains from taking sides while engaging in multiple partnerships. In contrast, a state pursuing a balance of power fully aligns with one power against another (a rising power or a power that poses a growing threat). Finally, the key tools employed in executing a hedging strategy involve using all available instruments in an opposite and mutually counteractive manner. As for a balancing strategy, the key tools are primarily military (alliances and armament), along with any other instruments and means available.[9]

When a state (such as the Philippines in this case) moves from a hedging-based foreign policy to a new strategy centered on balancing, this is called foreign policy restructuring. It is a multidimensional change that includes reformulating the state’s foreign policy orientations and the consequent shifts in policies, behaviors, tools, and roles. Therefore, this phenomenon is sometimes called reorienting foreign policy. It happens within a relatively short period, unlike normal gradual changes that occur over a relatively long period.[10]

Explaining the shift in Philippine policy toward China and the U.S.

Perhaps the first of the key variables that led Manila to abandon strategic hedging and even consider it a luxury it can no longer afford was the change of political leadership and the ascension of Marcos Jr. to the presidency in June 2022. The new president holds a negative view of China and has significant concerns about its regional ambitions and intentions. Marcos Jr.’s reorientation of the Philippines’ foreign policy has gained public support, especially his stance on the South China Sea dispute.[11]

Marcos Jr.’s policy toward China and the U.S. differs sharply from that of his predecessor, President Rodrigo Duterte (2016-2022). During the Duterte administration, the Philippines revived the strategic hedging policy it had been pursuing toward China since the mid-1970s, following a period of conflictual interactions under President Benigno Aquino III (2010-2016). On his first visit to China in 2016, President Duterte announced his “Realignment with China” policy. He downplayed the political tensions between the two countries resulting from the South China Sea dispute to revive and strengthen diplomatic and economic ties. This was clearly evident in China’s agreements and promises to inject significant investments and provide soft loans to finance numerous development projects in the Philippines. In 2017, Chinese exports to the Philippines increased by 26.4% compared to the previous year. Also, Filipino fishermen have been allowed to return to their work in the waters surrounding the disputed islands after years of being driven out.[12]

The conflict in the South China Sea, the growing Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific region, and U.S. support are among the key factors that have driven Manila to abandon its strategic hedging and reorient its policies toward adopting a strategy of positive balancing.

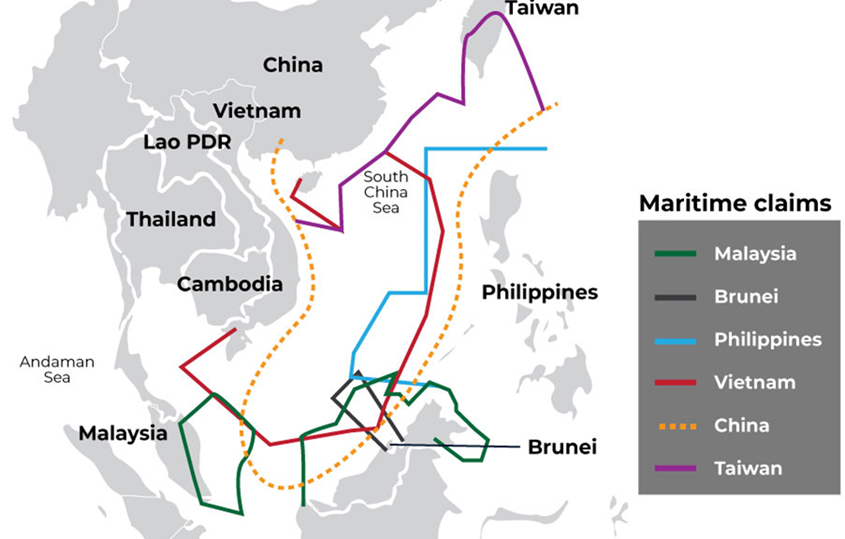

Tensions have recently escalated to dangerous levels in the South China Sea off the western coast of the Philippines, as China seeks to impose its control over almost the entire sea, overlapping with the exclusive economic zones of Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Beijing claims sovereignty over the entire strategic maritime area; claims that are rejected by the Philippines and other coastal states, which, in turn, demand the return of sovereignty to each country over its designated areas, according to their historical and legal rights, as stipulated in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)[13] (see the map below). To accentuate its claims, China uses the so-called “grey-zone tactics,”[14] leading to violent confrontations between Chinese and Filipino naval forces.

The dispute in the South China Sea, which is described as the “throat of global sea routes”[15] where nearly 30% of global maritime trade, valued at more than $3 trillion annually, passes through it, in addition to the vast hydrocarbon and fishery resources it contains, centers around a group of coral islands and maritime zones. The most important of these are the Paracel Islands, Spratly Islands, Scarborough Shoal, and Second Thomas Shoal.

Map (1)

Overlapping interests in the South China Sea

Source: Aristyo Rizka Darmawan, “ASEAN Outlook to solve South China Sea dispute?” The ASEAN Post, January 2020. https://shorturl.at/33pCb

The Philippines views the continuous interference of China in its maritime activities within its exclusive economic zone, particularly in the areas of Mischief Reef, Scarborough Shoal, and Second Thomas Shoal, as a violation of Philippine sovereignty and maritime law. Manila also asserts its sovereignty over the western part of the Spratly Islands, which it calls “Kalaya’an”, and refers to the area as the “West Philippine Sea.” In 2012, the Chinese seized Scarborough Shoal, an area that has been claimed by the Philippines for more than half a century. In 2016, an international tribunal at the Hague ruled the Philippines has exclusive economic rights in a 200-mile zone that includes, among others, Scarborough Shoal, and the Second Thomas Shoal, which makes China’s claim to sovereignty over it legally unfounded—a ruling that Beijing has decisively rejected. In reality, China maintains military presence at Mischief Reef, which it seized in the 1990s and transformed it into a military base, as well as Fiery Cross Reef, Subi Reef, and the Woody Islands, despite the ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration.[16]

Recently, clashes between the Chinese and Philippine coast guards in the South China Sea have intensified. In June 2024, Chinese Coast Guard personnel surrounded and attacked three Filipino supply boats that were on a mission to resupply forces stationed on the Second Thomas Shoal. The confrontation involved hand-to-hand combat and bladed weapons, resulting in injuries to a Filipino sailor and damage to the boats and the equipment they were carrying.[17]

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. strongly condemned China’s actions in the South China Sea and warned that his country would consider the killing of any Filipino by China “an act of war.”[18] In August 2024, a Chinese Coast Guard vessel rammed a Philippine ship on a routine resupply mission near the disputed Sabina Shoal. The incident marked a major escalation in the dispute between Beijing and Manila over sovereign rights in the waters off the western coast of the Philippines, moving the lines of conflict closer to the Philippine shore than ever before. Both Manila and Beijing have deployed Coast Guard ships around the island in recent months, and China has demanded the withdrawal of a Philippine Coast Guard vessel from Sabina Shoal. The vessel was in fact withdrawn,[19] although the Philippines claimed it was because of bad weather, running out of supplies, and the need to evacuate personnel requiring medical attention.[20]

Another factor that led the Philippines to strengthen its alliance with the U.S. at the expense of China is the failure of regional efforts through ASEAN or the ASEAN+1 meetings with China to reach a political settlement for the South China Sea dispute. In fact, the 2023 ASEAN Summit failed to issue a substantive joint statement to address the dispute, as so did the Australia-ASEAN Summit (March 2024) in Melbourne.[21]

Manifestations of a shift in the Philippine policy toward China and the U.S.

President Marcos Jr. has pursued an assertive stance toward China, particularly regarding the South China Sea dispute. This includes withdrawing from China’s Belt and Road Initiative and prioritizing geopolitical concerns over economic gains, a move only a few other countries in the region have made. In a speech he delivered at the Lowy Institute during his visit to Melbourne in March 2024, Marcos Jr. emphasized that he had a duty to defend his country’s territory in the South China Sea against Chinese actions.[22]

In March 2024, the Philippine military began implementing a new strategy to defend the country’s territory and economic interests, some days after a Philippine clash with Chinese vessels in the disputed South China Sea. In addition, the Comprehensive Archipelagic Defense concept was presented to be part of the plan to upgrade the country’s military capabilities and coordinate government efforts to give Filipino citizens and companies the right to freely explore natural resources within the country’s exclusive economic zone unimpeded.[23]

Since Marcos Jr. assumed the presidency, U.S.-Philippine relations have seen a positive transformation. He has allowed the U.S. to reactivate its military cooperation with Manila after years of curtailment under his predecessor, Rodrigo Duterte, and has pushed to enhance bilateral military, security, and political collaboration.[24] Manila has had a mutual defense treaty with the U.S. since 1951 and the two countries signed the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) in 2014.[25] In 2023, Manila allowed increased U.S. access to Philippine military bases and the storing of supplies in these bases, which the U.S. provided $128 million in 2024 to be upgraded.[26] In the same year, the U.S. also offered $500 million in military aid to reinforce the Philippine military and naval capabilities.[27]

In fact, the Philippines has become a trusted component of the U.S. defense strategy in the Indo-Pacific region, alongside Japan, South Korea, and Australia.[28]

Mutual visits have been one of the most important manifestations of change in the Philippines-U.S. relations. In March 2024, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Manila, where he underscored “Washington’s ironclad commitment” to help defend the Philippines in case of an armed attack against its forces. He was of course referring to an attack from China. President Marcos Jr. took part in the historic summit held in Washington in April 2024 along with U.S. President Joe Biden, and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, with the aim of enhancing regional security cooperation. The three leaders expressed “serious concerns” about Beijing’s “dangerous and aggressive behavior” in the South China Sea. President Biden also affirmed that “any attack on a Philippine aircraft, vessel, or armed forces in the South China Sea will invoke the Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT) binding Washington and Manila,” in a clear warning to Beijing.[29]

The most prominent development, albeit symbolic, in this regard was the statement by Admiral Samuel Paparo, Commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, during an international military conference in Manila on 25 August 2024. He said that the U.S. is open to consultations about escorting Philippine ships as they sail to resupply ships anchored in conflict zones with China. Beijing viewed such statements as only aggravating tensions.[30]

At the same time as conflict in the South China Sea escalated, military exercises between the Philippines and the U.S. (as well as Japan) intensified.[31] In this respect, Philippine and American forces conducted the “Balikatan” exercises in April 2024, which were the largest joint military drill ever held between the two countries. The exercises lasted three weeks, with the participation of nearly 17,000 soldiers in the Philippines and included operations in the South China Sea. Australia also participated in these exercises, during which the U.S. deployed Typhon Medium-Range Capability (MRC) missile systems that can fire M-6 and Tomahawk missiles to the Philippines. While it is true that the U.S. has not announced that the deployment of these systems to the Philippines is for purposes beyond the previous exercises, their presence is strategically indicative of the deepening of the U.S.-Philippine Alliance.[32]

In August 2024, while Chinese naval drills were underway around Scarborough Shoal, the Philippines, the U.S., Canada, and Australia conducted joint naval and air exercises, which were the first involving all four countries as a group, in the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone. The Philippines also held bilateral naval exercises with the United States (and Japan and Vietnam) in the South China Sea during July and August 2024.[33]

The Philippines is engaged in American alliances in the region, especially the Quad, joining forces with its members (Japan, Australia, and India) in a growing defense cooperation. Efforts to enhance defense cooperation between Japan and the Philippines have intensified since Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s visit to Manila in 2023. In July 2024, the two countries signed a bilateral defense agreement, known as the Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA), which allows the deployment of forces on each other’s territory for joint exercises or other operations, such as disaster relief operations. Under this agreement, Japan will be able to participate as a full member in the Balikatan military exercises conducted annually by the Philippines and the U.S. near Philippine shores, in which Japanese Self-Defense Forces previously took part as observer. Clearly, the key purpose of this agreement is to counter China’s growing military power and influence in the region. The signing of the agreement came amid rising Chinese threats toward Taiwan and the South China Sea, stoking fears of a possible conflict that could drag in the U.S. The agreement also came at a time of increasing worry felt by Japan and the Philippines, two longtime U.S. allies, regarding China’s expanding influence in the region.[34]

In addition to the agreement with Japan, the Philippines has a similar agreement with Australia and plans to sign another with France. This will further enhance the Philippines’ security partnerships within the network of alliances centered around the U.S.[35]

The Philippines and Australia cemented their relations by signing a strategic partnership in 2023, which also includes defense cooperation. More bilateral joint patrols in the South China Sea and other areas of mutual interest are also on the table. Australia intends to bolster its presence in the South China Sea through joint naval defense activities with the Philippines.[36]

Defense cooperation between the Philippines and India has also increased. The Philippines bought ‘BrahMos’[37] missiles, jointly developed by India and Russia, as part of its defense upgrade program. It is worth noting that the contract signed for the purchase of these missiles and their launch platforms in January 2022 includes training for military personnel who will operate these batteries, as well as technicians responsible for their maintenance in India. Previously, India offered the Philippines a line of credit to purchase Indian military equipment. Defense procurement from India, and potentially joint production as well, could play a crucial role in strengthening bilateral relations and enhancing Manila’s defense readiness.

The Philippines is also intensifying its defense cooperation with U.S. allies in NATO. It has signed a memorandum of understanding with Canada to enhance bilateral defense cooperation.[38] Furthermore, the Philippines and Germany set the groundwork in August 2024 for a defense agreement allowing joint military training, weapons sales, information sharing and closer collaboration between their forces.[39]

In summary, the Philippines has abandoned the longstanding hedging strategy it had followed toward China since the mid-1970s and is now working to establish a positive balancing (both internally and externally) in the face of Beijing. It is doing so by strengthening its alliance with the U.S. This paper has elaborated on the aspects of this dramatic shift (or restructuring) in Philippine foreign policy and presented a number of variables to explain it.

Despite Marcos Jr.’s enthusiasm and public support for his new foreign policy, this approach will face a significant test following the U.S. presidential elections in November 2024. If Donald Trump regains the presidency, it remains uncertain whether the U.S. will maintain its commitment to the region or fulfill its obligations to its allies. Recent comments from Taiwan seem to reflect some of these concerns.[40] Nevertheless, the momentum of the Philippines’ pivot toward the U.S. and tensions between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea are expected to rise in the near term, at least.

[1] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat, “The Philippines vows to remain in a disputed area of the South China Sea,” September 15, 2024. https://cl.gy/azvvd. [In Arabic].

Cecilia Vega, “Conflict between China, Philippines could involve U.S. and lead to a clash of superpowers,” 60 minutes, CBS News, September 15, 2024, https://shorturl.at/AMHqj.

[2] Indo-Pacific Defense Forum, “Philippine military personnel train with Allies and Partners in South China Sea,” August 9, 2024, https://cl.gy/BxVLr.

[3] Vega, “Conflict between China, Philippines.”

[4] Ayman Ibrahim Eldessouki, “Strategic Hedging in the Middle East,” Al-Siyassa Al-Dawliya 54, no. 215 (January 2019), pp. 33-34. [In Arabic].

[5] Mohammad Salman, “Strategic Hedging and Unipolarity’s Demise: The Case of China’s Strategic Hedging,” Asian Politics & Policy 9, no. 3 (July 2017), 357-360.

[6] Cheng-Chwee Kuik, “Explaining Hedging: The Case of Malaysian Equidistance,” Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs 46, no. 1 (2024): 46, muse.jhu.edu/article/925575.

[7] Kenneth Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, (1979)

[8] Mohammad Salman & Gustaaf Geeraerts, “Strategic Hedging and Balancing Model Under the Unipolarity,” paper presented at annual Midwest Political Science Association (Chicago), April 16-19, 2015, pp. 4-5.

[9] Ayman Eldessouki and Najla AlMidfa, “Malaysia’s Strategic Hedging toward China and the United States,” Trends Research & Advisory, September 16, 2024, https://bit.ly/4d7mA2c.

[10] Ayman Eldessouki, “The shift in the UAE foreign policy in the aftermath of the Arab revolutions,” Journal of the Faculty of Economics and Political Science 18, no. 4 (2017), 107-108. [In Arabic];

A. Rosati, M. W. Sampson III and J. D. Hagan, “The Study of Change in Foreign Policy,” in Foreign Policy Restructuring: How Governments Respond to Global Change, eds. J.A. Rosati, J.D. Hagan and M.W. Sampson III (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1994), 3-21.[11] Rahul Mishra and Peter Brian M. Wang, “The Philippines seeks out old friends and new,” The Interpreter, March 25, 2024, https://shorturl.at/CNYRE.

[12] Andrea Chloe Wong, 2017.

[13] X, Shi. “UNCLOS and China’s Claim in the South China Sea” Australian Defense College, 2015, p. 1

[14] The “grey zone” is part of China’s playbook with Taiwan and countries in the region with which it has territorial disputes. It refers to coercive geopolitical, economic, and military activities or tactics, as well as cyber and information operations, employed by the Chinese government to achieve its external objectives. These tactics go beyond standard diplomatic and economic activities but stop short of using military force. [In Arabic]. See: Bonny Lin, et al., A New Framework for Understanding and Countering China’s Gray Zone Tactics. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RBA594-1.html.

[15] Robert D. Kaplan, “The South China Sea is the Future of Conflict,” Foreign Policy, October 2011, https://shorturl.at/gYTkM.

[16] Ajeng Rizqi Rahmanillah, Tiara Putih Bastian, and Rizky Ihsan, “Indonesia’s South China Sea Policy: The Limits of Hedging,” Edunity Kajian Ilmu Sosial dan Pendidikan 2, no. 11 (2023),1279. DOI:10.57096/edunity.v2i11.177.

[17] Vega, “Conflict between China, Philippines.”

[18] “Japan, Philippines sign defense pact with eyes on China,” Al Jazeera, July 8, 2024, https://shorturl.at/mRwJH.

[19] Al-Sharq Al-Awsat, “The Philippines vows to remain in a disputed area in the South China Sea,” September 15, 2024, https://cl.gy/azvvd. [In Arabic].

[20] Al-Shorouk, “Philippine Foreign Minister: We did not make an agreement with China on withdrawing the ship from the South China Sea,” September 19, 2024, https://2u.pw/6EInGQgy.[In Arabic].

[21] Melanie Burton and Renju Jose, “Australia and ASEAN call for restraint in South China Sea, ceasefire in Gaza,” Reuters, March 6, 2024, https://shorturl.at/ePisc.

[22] Mishra and Wang, “The Philippines seeks out.”

[23] Sara Al-Neyadi, “The Philippines: Has it become part of the U.S. deterrence strategy against Beijing?” TRENDS Research & Advisory, May 31, 2023, https://2u.pw/UtCmReW. [In Arabic].

[24] Commodore Agus Rustandi, “The South China Sea Dispute: Opportunities for ASEAN to enhance its Policies in order to Achieve Resolution,” Center for Defense and Strategic Studies, 2016, p 3; Ahmed Qandil, “Balikatan Exercises 2024: The Philippines’ dilemma in the South China Sea between the American ally and the Chinese neighbor,” Future for Advanced Research and Studies (FARAS), May 10, 2024, https://shorturl.at/DlSfY. [In Arabic].

[25] U.S. Embassy Manila, Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) Fact Sheet, March 20, 2023, https://2u.pw/BmuV4Vn7.

[26] Cecilia Vega, “Conflict between China, Philippines.”

[27] “Philippines, US navies hold joint exercise in South China Sea,” Reuters, July 31, 2024, https://cl.gy/vDpQR.

[28] President of the Philippines: Manila will “vigorously Defend what is ours” in the South China Sea, Al-Sharq, May 18, 2024, https://shorturl.at/XgX0M. [In Arabic].

[29] Ahmed Qandil, “Balikatan Exercises 2024: The Philippines’ dilemma in the South China Sea between the American ally and the Chinese neighbor,” Future for Advanced Research and Studies (FARAS), May 10, 2024, https://shorturl.at/DlSfY. [In Arabic].

[30] Qandil, “Balikatan Exercises 2024”. [In Arabic].

[31] Qandil, “Balikatan Exercises 2024”. [In Arabic].

[32] Institute for the Study of War, Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, July 28, 2024, https://2u.pw/s1pJTsdM.

[33] Indo-Pacific Defense Forum, “Philippine military personnel train with Allies and Partners in South China Sea,” August 9, 2024, https://cl.gy/BxVLr.

[34] ABS-CBN News, “Philippines, Japan sign landmark defense pact,” July 8, 2024, https://shorturl.at/4Gd69.

[35] ABS-CBN News, “Philippines, Japan sign”.

[36] Australian Government, “Philippines country brief: Bilateral relations,” n.d., https://shorturl.at/OyLqa.

[37] Arab Security and Defence Website, “India and Russia working to extend BrahMos missile range to 500 km,” Defense and Security Arabia, April 8, 2019, https://shorturl.at/f2xwm. [In Arabic].

[38] Mishra and Wang, “The Philippines seeks out.”

[39] Indo-Pacific Defense Forum, “Philippine military personnel train with Allies and Partners in South China Sea,” August 9, 2024, https://cl.gy/BxVLr.

[40] Mishra and Wang, “The Philippines seeks out.”