In response to the growing geopolitical conflict between the United States and China in Southeast Asia and China’s gray zone[1] tactics in the region, most ASEAN countries opt for a hedging strategy. They are engaging in cooperative interactions with both major powers, strengthening their own military and economic capabilities, and diversifying their external partnerships.

In other words, most Southeast Asian countries prefer not to fully side with either the U.S. or China, a strategy known as “bandwagoning,”[2] nor do they wish to put themselves in a situation where they must choose between the two. As a result, these countries resort to a hedging strategy toward both competing powers. Their goals are to maintain a degree of strategic independence, secure flexibility in foreign policies, and build a stable regional environment. Malaysia is no exception to this.

Ironically, Malaysia did not adopt any form of hedging during the first decade following its independence in 1957. During that period, the then-small nation chose to align itself directly with Britain and, indirectly, with the U.S., maintaining a hostile policy toward China. However, from the late 1960s and early 1970s, Malaysia reoriented its foreign policy from a Western-aligned balancing to strategic hedging. This shift involved a practical change in Malaysia’s policy toward China, previously perceived as a source of threats, by engaging directly and politically with it.[3]

Malaysia has viewed itself as a country maintaining an “equidistant” stance between the U.S. and China. This means maintaining an active neutral, non-aligned position while seeking to form comprehensive but selective partnerships across various domains with all competing powers in the Indo-Pacific region. This approach aims to minimize risks, maximize benefits, and keep options open amidst uncertainty.[4]

This paper aims to examine the contours of the strategic hedging model presented by Kuala Lumpur and to elucidate how this middle power[5] has continued to pursue hedging despite the intensifying competition between the U.S. and China in the Indo-Pacific.

Theorizing Strategic Hedging

Strategic hedging entails that a “hedging” state engages with the powerful threatening state (PTS) to mitigate risks or avoid entering disproportionate conflicts. Simultaneously, the “hedging” state prepares for any potential confrontation with the PTS by developing its military and economic capabilities, and/or engaging in alliances with powers that rival the PTS.[6]

The main threat to the hedging state is a possible confrontation with the PTS (a major power or a key regional state). Such confrontation may take the form of an economic blockade, a diplomatic boycott, or even an armed confrontation. Hence, the behavior of the hedging state is driven by the fear of a potential confrontation with the PTS, given the significant gap in capabilities between the two parties. Here, strategic hedging works to minimize these threats by enhancing the military capabilities of the hedging state while avoiding engaging in hard balancing and developing economic capacities through various means, such as diversifying energy sources, increasing the number of trade partners, and acquiring advanced technology.[7] It is noted that the short-term costs accepted by the hedging state to enhance its own capabilities are far less burdensome than the potential costs of a sudden conflict with the PTS.

Therefore, hedging is defined as insurance-seeking behavior under high-stakes and high-uncertainty conditions. It seeks to mitigate and offset risks while maximizing returns via three approaches: active neutrality, inclusive diversification and prudent fallback cultivation. Hedging is conceived not only as a “middle” position between competing powers but also as an “opposite” position, where mutually counteractive measures are pursued to offset risks of uncertainties and cultivate fallback options.[8]

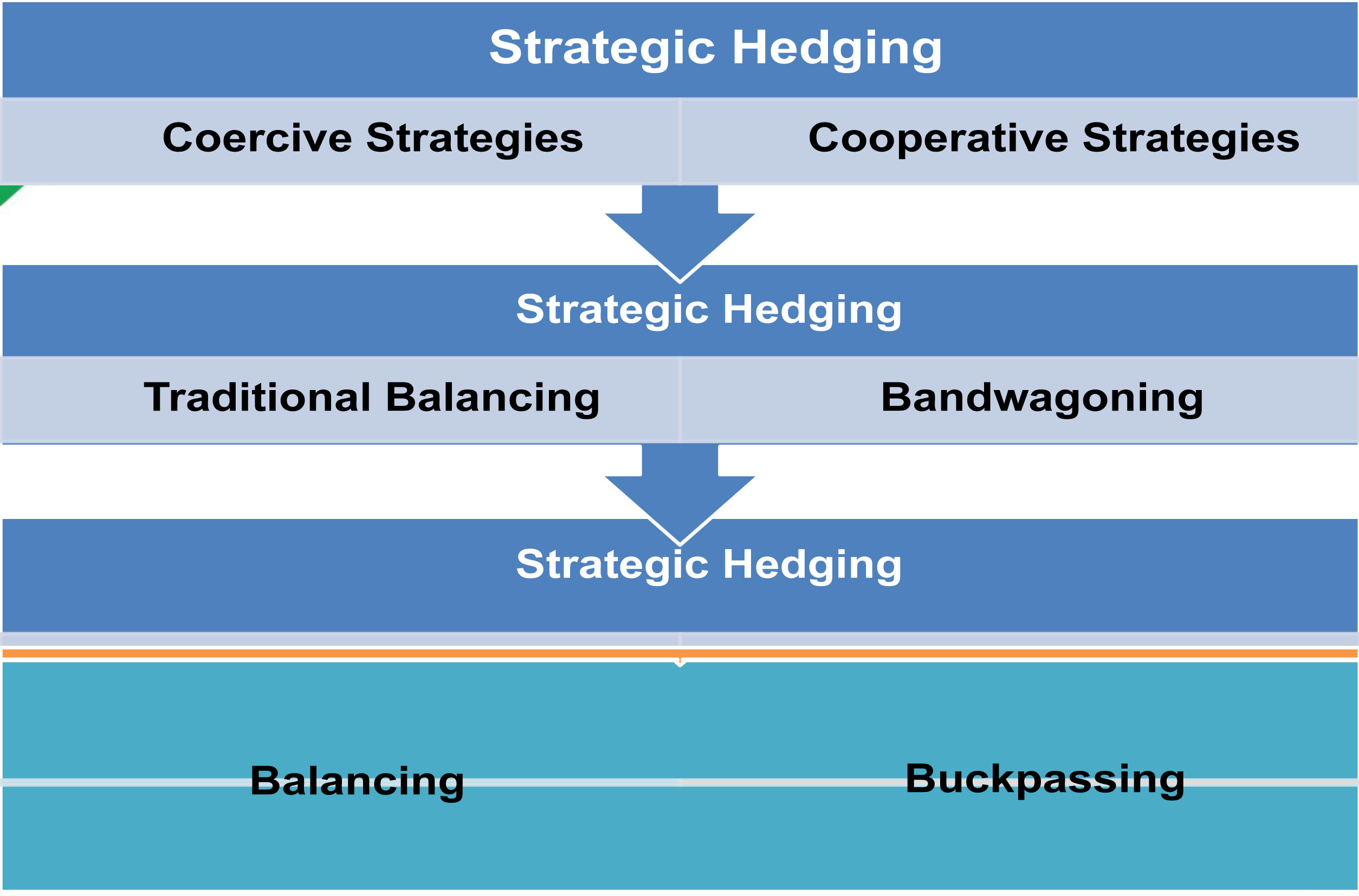

Conceptually, hedging is distinguishable from “balancing”, “bandwagoning” and “buckpassing”. Balancing means a security-seeking act of pursuing alliance (external balancing) and armament (internal balancing) to counter the PTS.[9] In contrast, bandwagoning refers to a utility-seeking act of accepting a subordinate role to a rising or dominant power in exchange for profit or security.[10] Buckpassing involves the tendency of nation-states to refuse to confront a growing threat in the hopes that another state will. It is a state policy of ‘staying out of it all together’. Put differently, buckpassing is a free ride on the balancing efforts of others.

Table 1: Hedging vs. Balancing and Bandwagoning

| Hedging | Bandwagoning | Balancing | Comparison Aspect |

| Not taking sides / neutral / equidistance / non-alignment via multi-alignments. | Fully siding with one power (a rising power or a growing threat). | Fully siding with one power against another (a rising power or a growing threat). | Macro-level alignment |

| Insurance-seeking: Mitigating and offsetting risks; Cultivating fallback options. | Utility-seeking: Maximizing profits/Minimizing security threat. | Security-seeking: Balancing the strongest power/ Balancing the most threatening power. | Principal drivers |

| All available instruments pursued in an opposite and mutually counteractive manner. | Primarily political means (displaying full deference) + any other tools. | Primarily military means (alliance and armament) + any other tools and instruments. | Principal means |

| Uncertainty in structural conditions (diffuse threats, uncertain supports). | Certainty in principal patron or principal threat. | Certainty in principal threat and principal patron. | Antecedent conditions |

As the following figure indicates, a state hedges, when it seeks a middle ground between coercive and cooperative strategies, hard and soft balancing,[11] balancing and bandwagoning, and confrontation and buckpassing.

Figure 1: Strategic Hedging as a Middle-position-strategy

In the real world, a hedging strategy involves several dimensions and features, as follows:

1. Mixing policy tools:

The hedging strategy combines both cooperative and confrontational policy mechanisms. However, the use of a mix of policy tools is a necessary but not sufficient condition for strategic hedging; a hedging strategy must also include contingency planning for unfavorable future scenarios. Additionally, one requirement of hedging is the ability to pass risks onto others. For example, many ASEAN states pass security risks and burdens onto the U.S., as it provides public goods like freedom of navigation and takes on the primary responsibility for managing Chinese behavior.[12]

2. Engagement and participation:

Engagement means establishing and maintaining communication with major powers (or the PTS) to create channels for dialogue and increase the “opportunity to express” and influence the political choices of these actors. Participation involves institutionalizing relations with major powers (or the PTS) through diplomatic networking, involvement in international and regional institutions, and limited bandwagoning. This aspect of hedging also includes security and defense cooperation, such as the participation of the hedging state(s) in formal alliances with regional or major powers opposed to the policies of the threatening state, and the establishment of cooperative relationships in political, economic and social fields with the powerful threatening state.

When engagement and participation are combined, they serve to help major powers understand and integrate into the existing system, aiming to neutralize the revisionist tendencies of the dominant power.[13]

3. Limited Bandwagoning:

This refers to a policy driven by the desire to gain current or future rewards by forging a partnership with a big power that shows potential for supremacy or with the powerful threatening state through selective deference or selective collaboration on key external issues, but without accepting a subordinate position.

4. Active neutrality:

The hedgers adopt a neutral external behavior toward crises/conflicts in which the PTS is a party or perhaps adopting an external interventionist behavior that focuses entirely on mediation and good offices. This approach can be termed “active neutrality”. However, it is important to emphasize that a hedging strategy is different from neutrality; neutrality compels the state to refrain from intervening in a conflict and to maintain uniform behavior toward all parties involved. In contrast, hedging allows the state to cooperate simultaneously with both the adversary state and the power or powers allied against it.

5. Separating issue areas:

A hedging state (or states) resorts to separating issue areas to expand the strategic space for its foreign policy. Separating issue areas involves a hedging state allying with other states on different issues to benefit from their capabilities. For instance, East Asian countries prefer to cooperate with the U.S. on security issues but engage with China on economic issues. Diversifying partners is based on the strengths and characteristics of these partners. For example, China and the U.S. are highly prioritized in the choices of East Asian countries, followed by Japan, the European Union, and India.[14]

In this context, hedging states pursue a policy based on economic pragmatism toward the stronger or threatening state. Economic pragmatism refers to the situation where a state seeks to maximize economic gains from its direct trade and investment ties with the state that threatens its national security, regardless of any political problems that may exist between them. In this regard, economic pragmatism is one of the policies endorsed by all ASEAN countries in their relations with China.[15]

6. Diversification of partners:

Diversification of partners is based on the characteristics and strengths of the partners and seeks to develop the hedging state’s relations with a number of states, both within and outside the region, in economic, defense and strategic areas, to avoid reliance on a specific partner. The diversification of partners is contingent upon the strengths and characteristics of those partners.[16] Partner diversification is seen as a logical or natural outcome of the hedging strategy. Rejecting a binary logic (either siding with one great power or the other) opens the strategic space for third parties to engage in relations with hedging states and provide them with alternative and comprehensive strategic options.[17]

Based on the above, it can be argued that a hedging strategy involves a mix of cooperation and conflict, which is why it is described as “mixed”. It enables states that follow it to engage in economic and socio-political cooperation with the threatening state while employing military, economic and diplomatic mechanisms to balance the source of the threat.[18] This means that the hedging state seeks a middle path. According to Evelyn Goh, hedging establishes a middle position for the state by avoiding choosing one party at the expense of the other.[19]

States do not follow a single pattern of strategic hedging; the patterns of strategic hedging vary according to the target country, motivation and level of engagement. Based on the target, distinction can be made between mono hedging (a state hedges against a single PTS) and dual hedging (a state hedges against two states that it perceives as threats to its national security).[20] China’s hedging against the U.S. is one of the most prominent examples of a state employing strategic hedging toward a single state. Most Southeast Asian countries are prime examples of states that practice dual hedging in their foreign policies toward China and the U.S.

Based on the hedgers’ motivations, a distinction can be made between the two types. Type A hedging is driven by the fear of a possible clash with the PTS. It involves some enhancement of the military capabilities of the hedging state but falls well short of the internal or external hard balancing that might provoke the PTS and lead to a dispute, crisis, or armed confrontation. Type A hedging may be economic, diplomatic, or even military in form. In this case, reference can be made to China’s hedging against the U.S. in the Indo-Pacific. Type B hedging is followed by hedgers aiming to address macro-level systemic imbalances. It refers to actions that address the potential loss of public goods or subsidies currently being provided by the system leader. Here the behavior of European states, especially France and Germany, toward the U.S. comes to mind. The European Union’s decision to develop some independent military capabilities in order to avoid too much reliance on U.S. forces.

Additionally, according to the degree of engagement, we can differentiate between light hedging and heavy or strong hedging. These two types of hedging differ in at least three aspects. First, states that engage in either light or heavy hedging recognize various risks in the world, but those in the first category tend to perceive lighter shades of risks and dangers, preferring to minimize risks whenever possible. Second, light or heavy hedgers see the need to pursue risk mitigation measures, when necessary, but the former prefer less confrontational and lower-level approaches. Third, while light and heavy hedgers recognize the need for countermeasures and reciprocal responses to offset risks, light hedgers tend to show more respect than challenge toward larger powers, whereas heavy hedgers are more willing to challenge, oppose, and even confront stronger powers when their core interests are at stake.[21]

From Balancing to Hedging: Explaining the Restructuring of Malaysian Foreign Policy

As a result of structural changes in the late 1960s and early 1970s, particularly the British “East of Suez” policy, Malaysian leaders began to recognize that fully aligning with one side against another could yield significant benefits for their country but also carry substantial risks. They also realized that they could no longer rely on their Western patrons for security protection, prompting them to engage directly with China. Put differently, security concerns became the primary driver for the restructuring of Malaysian foreign policy. Given the reduction of Western strategic presence, Malaysian elites—like the leaders of other ASEAN countries—began to see that reducing friction and normalizing relations with China were necessary steps to mitigate the threats posed by Chinese-supported communist movements. As a result, Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak Hussein (1970–76) replaced Malaysia’s previous pro-Western stance with a policy of non-alignment and regional neutrality. The long negotiations for normalization between Malaysia and China culminated in May 1974 when Abdul Razak visited Beijing, making Malaysia the first ASEAN country to establish official relations with China. This move not only marked Malaysia’s shift away from balancing but also represented the first such shift within ASEAN, followed by similar moves by the Philippines and Thailand.[22]

Thus, Malaysia ceased its full alignment with the West and its overt confrontation with China. Instead, it sought to mitigate the risks of the political and security situation by isolating the ethnic Chinese minority from Beijing’s influence while maintaining defense ties with Western powers and simultaneously establishing economic and diplomatic relations with China. Over the next half century, Malaysia consistently adopted a neutral, non-aligned policy. In addition to joining the Non-Aligned Movement in 1970, Malaysia began to use ASEAN as the cornerstone of its foreign policy.

Malaysia’s regional policy and non-aligned stance did not prevent it from developing and maintaining defense partnerships with countries far beyond its geographical surroundings, particularly with the U.S. and other Western nations, as well as with neighboring countries such as China and other Asian states. Although Malaysia’s defense and security cooperation arrangements with China pale in comparison to those with the U.S., its decision to maintain concurrent security relations with both powers, while also engaging in other partnerships, reflects its neutrality and “equidistant” stance. However, being equidistant does not mean being equally distant or close to competing powers but rather maintaining a neutral and non-aligned overall position while simultaneously seeking comprehensive but selective partnerships with all powers in various domains at the micro-level, focusing on risk mitigation, benefit maximization, and keeping options open amid uncertainty.[23]

While changing structural factors led to the shift from balancing to hedging, local circumstances determined the pace and pattern of this shift. In fact, Malaysia presents a model of light hedging in East Asia. PM Abdul Razak’s rapprochement with China was partly aimed at restoring domestic stability and the ruling elite’s legitimacy after the electoral setback suffered by the ruling coalition in May 1969 and the subsequent ethnic conflict between Malays and Chinese.[24]

Structural uncertainties deepened and persisted in the post-Cold War era, leading Malaysia and other ASEAN countries to maintain and even expand their “equidistant” policy. In addition to solidifying its role in ASEAN and ASEAN-led institutions, defending non-alignment and South-South issues, and strengthening ties with Islamic countries, Malaysia also deepened its neutral stance toward major powers.[25]

Malaysia’s post-Cold War “equidistant” policy does not equate to passive non-alignment but rather signifies active neutrality and adaptability to changing circumstances. Kuala Lumpur actively pursued this policy by engaging with major powers simultaneously to maintain its non-aligned stance, employing countermeasures to address multiple risks, keeping options open, and exploring ways to adapt to shifting power dynamics. This included taking the initiative to elevate certain partnerships when the PTS became too strong or unpredictable, and expanding alignment pathways when the international power structure became more ambiguous.[26]

Key Features of the Malaysian Hedging Model

By the end of the Cold War, Malaysia’s relations with the U.S. were strong and well-institutionalized. Despite occasional political differences, especially during Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s first tenure (1981–2003), Malaysian-U.S. relations were close and broad, encompassing strong economic ties, human exchanges in education, technology, socio-cultural fields, and military and security cooperation.

While continuing to develop stronger developmental and defense relations with the U.S., Kuala Lumpur took the initiative to engage with China on both bilateral and regional levels. Malaysia sent an official delegation to Beijing when China was isolated by the West following the Tiananmen Square incident in June 1989. Mahathir Mohamad invited Chinese Foreign Minister Qian Qichen as a guest of the Malaysian government to attend the opening session of the ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Kuala Lumpur in July 1991, marking the beginning of a dialogue between ASEAN and China. Efforts to develop relations between Malaysia and China and between ASEAN and China intensified, paving the way for broader regional integration. By the late 2000s, China had emerged as Malaysia’s prime trading partner, and by mid-2010, China had become a major investor in Malaysia.[27] In 2022, China was Malaysia’s top trading partner, with bilateral trade valued at around $130.5 billion, ahead of Singapore ($89.7 billion) and the U.S. ($62.6 billion).[28] Despite growing concerns in Malaysia about China’s intentions in the South China Sea, where China has become more assertive near Malaysian waters, Kuala Lumpur has developed close defense and security cooperation with China since 2010.[29]

Malaysia has demonstrated both deference and challenge in its interactions with the U.S. as reciprocal countermeasures. In 2004, Malaysia challenged the U.S. when it proposed deploying U.S. forces in the Malacca Strait to counter potential maritime piracy and terrorism threats. Kuala Lumpur insisted that regional security issues should not compromise its sovereignty. In September 2021, when the AUKUS, a trilateral security pact between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the U.S., was announced, Malaysia challenged the Western powers, expressing concerns that the alliance could exacerbate regional tensions. Despite its initial vocal objection to the pact, AUKUS has not caused a dramatic shift in Malaysia’s relations with Australia, the UK, and the U.S. Instead, Kuala Lumpur has continued to work with the three powers as important strategic partners. In fact, Malaysia has a complicated relationship with AUKUS. While it may seem that Malaysia has not followed through on its condemnation, its response is complicated by a complex domestic political climate and an increasingly tense geopolitical environment.[30]

Under Prime Minister Najib Razak (2009–2018), Malaysia showed consideration for U.S. interests and preferences on issues ranging from Iran and North Korea to nuclear non-proliferation and economic initiatives. Malaysia was a signatory to the U.S.-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the U.S. proposal known as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). Malaysia’s mixed policy of selective compliance and challenge can also be seen in its approach toward China, particularly on issues such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the South China Sea, and human rights in Xinjiang. By implementing such reciprocal and simultaneous countermeasures, Malaysia avoids the risks of falling into the orbit of any single power, thereby maintaining its independence and neutrality on a macro level. When the Obama administration implemented the “Pivot to Asia” policy[31] in November 2011, Malaysia embraced Washington’s initiatives, and Malaysian-U.S. relations were elevated to a “comprehensive partnership” in 2014, shortly after Malaysia and China established a comprehensive strategic partnership in 2013.[32]

Malaysia’s partnerships with the U.S. and China are, in many ways, “alignments” rather than formal alliances.[33] Its partnership with both powers is largely driven by the convergence of strategic interests, developed out of the ongoing need to establish closer cooperation, and maintained through regular institutionalized collaborative mechanisms and high-level consultative processes. These characteristics make Malaysia’s alignment with both countries distinct from other less strategic, less institutionalized, and narrower partnerships. As mentioned earlier, Malaysia’s alignment with both powers is broad and multi-dimensional, covering nearly all areas. This comprehensive and multi-layered approach has enabled Malaysia to maintain its active neutrality at the macro level. On various occasions, Anwar Ibrahim, the current Malaysian PM (2022-present), has used the term “ally” to describe both the U.S. and China. This term is technically inaccurate, as Malaysia’s partnership with either power does not involve any mutual defense commitments. However, Ibrahim’s repeated use of the term “ally” to describe both reflects how Malaysian elites view their partnerships with both great powers as de facto alliances, albeit with an uneven focus across different domains.[34] For instance, while the Malaysia-American defense partnership is much closer than its Malaysian Chinese counterpart, the Malaysian-Chinese diplomatic and developmental ties are more diverse than those between Malaysia and the U.S.

Malaysia’s hedging strategy is based on the principle of diversifying partners. Besides the U.S. and China, Malaysia’s partners range from geographically proximate countries in the Indo-Pacific, such as Australia, South Korea and India, to geographically distant countries, such as Russia and the European Union. Malaysia also expanded its engagements with those partners across defense, diplomatic and developmental domains.

Russia has been among the primary arms suppliers to Kuala Lumpur, particularly for fighter jets. However, this appears to be changing as Malaysia’s Russian-made fighter jets face several shortcomings, and sanctions on Moscow limit Kuala Lumpur’s ability to purchase arms from Russia. Therefore, Malaysia is turning elsewhere for arms purchases, with South Korea emerging as one of the most prominent options. Last year, the two countries signed a contract for the sale of 18 South Korean-made FA-50 fighter jets. Additionally, Malaysia seeks to enhance local manufacturing capabilities for defense products through cooperation and technology transfer from other countries.[35]

Australia and Malaysia elevated their bilateral relationship to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP). The CSP covers trade and investment, education and cyber, defense and regional security, as well as new areas such as the digital economy and climate change. In 2022-23, Australia was Malaysia’s 10th largest trading partner. In 2023, bilateral trade was valued at $22.8 billion. The two countries have been linked by a bilateral Free Trade Agreement since 2013. Australia and Malaysia are also parties to the Agreement Establishing the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Area (AANZFTA), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF).[36]

The defense relationship between Australia and Malaysia has continued to mature under the auspices of the Five Power Defence Arrangements (1971) and the Malaysia-Australia Joint Defence Program (1992). In addition to numerous reciprocal secondments, courses and annual exercises, Malaysia hosts an ongoing Australian Defence Force presence at Royal Malaysian Air Force Base Butterworth.[37]

India and Malaysia also signed a comprehensive strategic partnership during Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s visit to India in August 2024. The bilateral trade volume between India and Malaysia stands at about $20 billion (2023). Malaysia ranks as the 16th largest trading partner of India, while India is among Malaysia’s top 10 trading partners. The two countries are focusing on cooperation in emerging technologies, which could drive technological innovation, expand economic opportunities, and facilitate the employment of Indian labor in Malaysia.[38]

In summary, Malaysia’s hedging policy is active and adaptable. The policy is characterized by not targeting any specific country and relies on a mix of compliance and defiance toward major powers. By applying these two contrasting approaches of deference and challenge, Malaysia actively asserts its neutrality, diversifies its external ties comprehensively and keeps its options open.[39]

[1] The “gray zone” refers to a set of tactics employed by China in its dealings with Taiwan and other neighboring countries with which it has territorial disputes. These tactics include geopolitical, economic and military coercive activities, as well as cyber and information operations. These actions are used by the Chinese government to achieve its foreign policy objectives, going beyond regular diplomatic and economic activities yet stopping short of direct military force. See: Bonny Lin et al., “A New Framework for Understanding and Countering China’s Gray Zone Tactics,” RAND Corporation, 2022, https://shorturl.at/CV2ft.

[2] Laos and Cambodia are among the most dependent or aligned countries with China, and they follow a strategy of bandwagoning toward it. Meanwhile, the Philippines has restructured its foreign policy to balance against China. See: Cheng-Chwee Kuik and Gilbert Rozman, “Light or Heavy Hedging: Positioning between China and the United States,” in Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies 2015, vol. 26, edited by Gilbert Rozman, Washington, D.C.: Korea Economic Institute of America, 2015, 2.

[3] Kuik Cheng-Chwee, “Explaining Hedging: The Case of Malaysian Equidistance,” Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs 46, no. 1 (2024): 52, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/925575.

[4] Kuik, “Explaining Hedging,” p. 46.; Elisabeth Gosselin-Malo, “Malaysia is becoming wary of its Russian-made weapons,” Defense News, February 21, 2024, https://2u.pw/oTR1EFBq.

[5] Since 2003, Malaysia has ascended into the ranks of the middle powers in the international system. Bruce Gilley, “Will Malaysia Become an Active Middle Power?” Australian Journal of International Relations 64, no. 3 (2024): 293–311.

[6] Ayman Ibrahim Eldessouki, [“Strategic Hedging in the Middle East”,] Al Siyassa Al Dawliya 54, Issue 215 (2019), 33-34.

[7] Mohammad Salman, “Strategic Hedging and Unipolarity’s Demise: The Case of China’s Strategic Hedging,” Asian Politics & Policy 9, no. 3 (July 2017), 357-360.

[8] Kuik, “Explaining Hedging,” 46-47.

[9] Kenneth Waltz, Theory of International Politics (McGraw-Hill, 1979).

[10] Randall Schweller, “Bandwagoning for Profit: Bringing the Revisionist State Back In,” International Security 19, no. 1 (1994): 72–107.

[11] Soft balancing relies on soft power tools, while Strategic hedging is a mixed/hybrid strategy of cooperation and conflict, relying on both soft and hard power tools.

[12] Ryan Yu-Lin Liou and Philip Szue-Chin Hsu, “The Effectiveness of Minor Powers’ Hedging Strategy: Comparing Singapore and the Philippines” (PhD diss., University of Georgia, 2019), 3.

[13] Kuik, “The essence of hedging: Malaysia and Singapore’s response to a rising China,” Contemporary Southeast Asia 30, no. 2 (2008): 167-169.

[14] Kuik and Gilbert Rozman, “Light or Heavy Hedging,” 3-4.

[15] Kuik, “The Essence of Hedging,” 168-169.

[16] Ola Mansur and Ayman Eldessouki, [Strategic Hedging in Iranian policy towards the United States ] (Doha: Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, 2022), 45-46, 56-57.

[17] Fabio Figiaconi, “Southeast Asia’s Hedging: A Strategic Opportunity for the European Union?,” EGMONT Policy Brief 314, September 2023, https://2u.pw/z8Hd6Hh.

[18] Ayman Eldessouki, [“Strategic Hedging: Theory and Practice”,] Trending Events, Issue 18 (2016): 17-21.

[19] Evelyn Goh, Meeting the China Challenge: The U.S. in Southeast Asian Regional Security Strategies (Washington, D.C.: East-West Center Washington, 2005), 2.

[20] Mansur and Eldessouki, [“Strategic hedging in Iranian”], 64-65.

[21] Kuik and Rozman, “Light or Heavy Hedging,” 1–9.

[22] Kuik, “Explaining Hedging,” 53-54.

[23] Kuik, “Explaining Hedging,” 45-46.

[24] Kuik, “Explaining Hedging,” 55-56.

[25] Kuik, “Explaining Hedging,” 56.

[26] Kuik, “Explaining Hedging,” 56.

[27] Kuik, “Explaining Hedging,” 56-57.

[28] OEC, Malaysia, https://shorturl.at/ShBe5.

[29] Kuik, “Explaining Hedging,” 45.

[30] Izzah Ibrahim, “Malaysia’s Position on AUKUS – A question of stagnation or pragmatism?,” Perth USAsia Centre, December 2023, https://shorturl.at/fztuj.

[31] Kenneth G. Lieberthal, “The American Pivot to Asia,” Brookings, December 21, 2011, https://shorturl.at/h2VDj.

[32] Kuik, “Explaining Hedging,” 57.

[33] Thomas S. Wilkins, “‘Alignment’, Not ‘Alliance’–The Shifting Paradigm of International Security Cooperation: Toward a Conceptual Taxonomy of Alignment,” Review of International Studies 38, no. 1 (2012): 53–76.

[34] Kuik, “Explaining Hedging,” 58.

[35] Elisabeth Gosselin-Malo, “Malaysia is becoming wary of its Russian-made weapons,” Defense News, February 21, 2024, https://2u.pw/oTR1EFBq.

[36] Australian Government, “Malaysia country brief,” n.d., https://shorturl.at/Ls0ZO.

[37] Australian Government, “Malaysia country brief.”

[38] Prime Minister’s Office, India, “Joint Statement on India – Malaysia Comprehensive Strategic Partnership,” August 20, 2024, https://shorturl.at/R5qTM.

[39] Kuik, “Explaining Hedging,” 57-58.