China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), originally launched as the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative by President Xi Jinping in 2013, is a cross-border initiative aiming at boosting connectivity and economic development among countries along the routes of the BRI’s two main components, the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. China launched the BRI to build a more effective trading path to Europe, Russia, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. It aims to promote investment and consumption, cooperation, people-to-people bonds and cultural exchange, create jobs and demand, and encourage trade. China intends to achieve its goals by financing infrastructure projects in key places/cities of the two “routes,” enabling it to streamline its trading paths, contribute to economic growth along the two routes, and increase its “soft power.”

The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) was launched at the G20 Summit in India on 9 September 2023. It also has two components that will connect India with the Gulf and Middle East and proceed to connect the latter to Europe via Greece. It has been touted as an alternative to the BRI, with the aim of limiting China’s growing influence in the Middle East.

In May 2024, China’s President Xi visited Europe to discuss issues that could affect relations between the European Union (EU) members and China. This could potentially impact both the BRI and the IMEC.

This paper will address the two initiatives to better understand their nature and whether they compete. It will also address the impact of the above events and initiatives on the Middle East in general and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states specifically.

The framework of the BRI

The BRI connects participating countries through six economic cooperation corridors. Aligned with the United Nations Charter’s Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, it has adopted the values of being open for cooperation, harmonious and inclusive, following market operations, and seeking mutual benefit.

The trade routes along the two main components, i.e., the land-based “Silk Road Economic Belt” and the ocean-going “Maritime Silk Road,” provide a framework for cooperation, trade, investment and development for the countries that comprise the BRI. The vision of the BRI was originally to connect 64 countries via infrastructure projects between Western Europe and Asia at a cost ranging between US$4 and US$8 trillion. It is the primary funder of many of these projects.

The BRI connects China to Africa, Europe, Russia, and Central Asia. The six international economic cooperation corridors that form the “Belt”, are as follows:[1]

- New Eurasia Land Bridge

- China-Mongolia-Russia

- China-Central and Western Asia

- China-Indochina Peninsula

- China-Pakistan

- Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar

The “Road” is formed by three routes:[2]

- The China-Indian Ocean-Africa-Mediterranean Sea

- The China-Oceania-South Pacific

- The Arctic Ocean to Europe

The framework will eventually consist of a network of railroads, roads, pipeline connections, fiber-optic cables, ports, and upgraded telecommunication networks, which will much more efficiently connect China to the rest of the world. As for whom the BRI will be beneficial, China has been quite clear that the initiative will be inclusive. This means that even countries that are not on the stipulated routes will be able to tap into the benefits of the BRI, as many have done.

According to Banerjee (2016), the original cooperation priorities of the BRI focused on policy coordination, facilitating connectivity (infrastructure), unrestricted and free trade across borders, financial integration (investment and financing systems), and strengthening people-to-people contacts.[3]

China initiated the following financial institutions and funding mechanisms:[4]

- The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was launched in 2015 with a capital of US$100 billion.

- The BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) started with a capital base of US$100 billion.

- The US$40 billion Silk Road Fund (SRF) was established in 2014 to boost development along the BRI and strengthened by a further US$14.5 billion in May 2017.

- The South-South Climate Cooperation Fund, worth approximately US$3 billion, was announced in 2015 to assist developing countries with climate issues.

- In August 2016, the China EXIM Bank launched a US$1 billion industrialization program with the African Export-Import Bank.

The BRI’s political cooperation mechanism enhances the roles of bilateral and multilateral cooperation mechanisms, using existing mechanisms to intensify communication and promote regional cooperation. On financial integration, the BRI adds multilateral funding via the AIIB, the NDB, etc.

The current status of the BRI

The BRI currently represents approximately 30% of the world’s GDP, which is set to increase to nearly 67% by 2040. According to the World Bank, the BRI could, by 2030, “lift 7.6 million out of extreme poverty and 32 million out of moderate poverty.”

According to a study by Garcia-Herrero and Schindowski (2023), the BRI had officially expanded to 149 member states by 2022. The potential benefits of the BRI to Europe are clear when it is shown that Europe’s expected trade gains are 6% above the non-BRI benchmark case (based on a 2017 case study) and 3% above trade gains in Asia.[5]

At a global level, the BRI has been accepted and promoted at institutions such as the UN’s General Assembly and Security Council, the UNDP, the WHO, and the WTO.[6]

The BRI has also supported regional integration and global development by supporting the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the EU’s Strategy on Connecting Europe and Asia, the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025, the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific, and the African Union’s Agenda 2063.[7]

The BRI has also coordinated with many bilateral initiatives. These include Egypt’s Suez Canal Corridor Project, Kazakhstan’s Bright Road economic policy, Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union framework, Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, Qatar’s Vision 2023, and Egypt’s Vision 2023. By June 2023, 150 countries and 30 international organizations had signed more than 200 BRI agreements with China, indicating the huge and growing interest in it.[8]

This growing interest in the BRI was evident in the number of countries attending the three BRI Forums since 2017. The third BRI Forum, hosted in October 2023 and attended by representatives from more than 150 countries, addressed topics such as promoting unimpeded trade, enhancing maritime cooperation, promoting a clean Silk Road, strengthening think tank exchanges, enhancing people-to-people exchanges, and strengthening subnational cooperation.[9]

BRI partner countries have also expanded practical cooperation through major multilateral platforms such as the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum, China-Central and Eastern European Countries Cooperation, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, and the World Economic Forum.[10]

By the end of June 2023, the Silk Road Maritime network had reached 117 ports in 43 countries. As for the Air Silk Road, China signed bilateral air transport agreements with 104 BRI partner countries and opened direct flights with 57 to facilitate cross-border transport.[11] These are merely examples of the expansion of the BRI infrastructure network.

Trade between China and its BRI partners grew at an average annual rate of 6.4% from 2013 to 2022 to reach US$19.1 trillion. In 2022, trading between China and its partners reached nearly US$2.9 trillion, constituting 45.4% of China’s total foreign trade, and representing an increase of 6.2% compared with 2013. An excess of 80 countries and international organizations had, by the end of June 2023, subscribed to the “Initiative on Promoting Unimpeded Trade Cooperation Along the Belt and Road.” China has signed 21 free trade agreements (FTAs) with 28 countries and regions.[12]

There has also been progress on project funding. The SRF had, by the end of June 2023, committed investments amounting to US$22 billion in 75 projects. The AIIB members had grown to 106, while it had approved investments of US$43.6 billion in 227 projects in transport, energy, public health, etc.[13]

In the social sphere, cities from 60 BRI partners have formed more than 1,000 pairs of friendly cities with their Chinese counterparts. The Silk Road NGO Cooperation Network, created by 352 NGOs from 72 countries, has launched over 500 projects and activities. It is an important platform for collaboration between NGOs in these countries.[14]

The Griffith Asia Institute (GAI) (2023) provides the following view of the status quo:[15]

- Since 2013, cumulative BRI engagement has reached US$1.053 trillion, with US$634 billion in construction contracts and US$419 billion in non-financial investments.

- In 2023, the BRI saw 212 deals worth US$92.4 billion (2022 – US$74.5 billion) in finance and investments.

- In 2023, investments in technology (+1046%) and metals and mining (+158%) grew significantly.

- Chinese companies target metals and mining relevant to the green transition (e.g., lithium) and batteries for electric vehicles (US$8 billion in batteries).

- In 2023, private-sector companies continued to dominate BRI, although construction contracts were dominated by state-owned enterprises.

- GAI believes that 2024 will see a strong BRI focus on renewable energy, mining and related technologies.

- It expects future engagements in six project types: high-visibility projects (railways, etc.), ICT (data centers, etc.), manufacturing in new technologies (batteries, etc.), renewable energy, resource-backed deals (e.g., mining, oil, gas), and trade-enabling infrastructure (pipelines, roads, etc.).

Overall, the progress of the BRI since its inception in 2013 has been remarkable.

Arab world and the BRI

In the GCC region, all six member states are BRI partner countries, i.e., Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, and Bahrain. Egypt and Jordan, although not GCC members, are also prominent BRI partners.

According to President Xi, China has established comprehensive strategic partnerships with 12 Arab states and signed documents on BRI cooperation with 20. In addition, 17 Arab countries have expressed their support for the Global Development Initiative (GDI), 15 have become members of the AIIB, and 14 have participated in the China-League of Arab States Cooperation Initiative on Data Security.[16]

In the Arab world, the following initiatives were hosted, signed, or participated in:[17] [18] [19] [20] [21]

- The China-Arab States Expo

- The China-UAE Industrial Capacity Cooperation Demonstration Zone

- The China-Egypt TEDA Suez Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone

- The China-Arab Countries Interbank Association

- The China-Arab States Forum on Radio and Television Cooperation

- The Arab States Broadcasting Union

- China-Arab States Health Cooperation

- The China-League of Arab States Cooperation Initiative on Data Security

- BRICS Digital Economy Partnership Framework

- The China-Arab Online Silk Road

- The China-UAE Space Debris Joint Monitoring Center

- Chinese investment in the Duqm Port (Oman, 2018)

- Chinese construction engagement in the Middle East: The region received 36.7% of total BRI construction engagement in 2023, a 31% increase from 2022. Saudi Arabia received US$5.6 billion (US$2.6 billion in 2022), and the UAE US$2 billion.

- Saudi Arabia ranked second after Russia on BRI Project Nations based on project value since 2011 (US$152.74 billion) compared to Russia’s US$231.58 billion. Egypt ranked ninth (US$73.55 billion), and the UAE tenth (US$49.50 billion).

- The BRI contributed to the Vision 2030 of Egypt, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia.

- China mainly imports energy from the GCC, primarily from Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

- In 2023, Saudi Arabia received the most energy engagement (US$3.7 billion). Between 2013 to 2023, Saudi Arabia received the third-highest energy engagement from China and a significant share (19%) of green energy engagement.

- Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, and the UAE were other GCC countries that received significant Chinese energy engagement in 2023.

- China invested in a copper processing plant in Saudi Arabia.

- In 2023, shipping and port-related projects with Saudi Arabia were announced to support Aramco’s shipping projects.

China Energy Engineering Group Co Ltd has been developing oil-related energy projects in Saudi Arabia and other parts of the Middle East. In November 2022, it started building a 2.6-GW photovoltaic project in Saudi Arabia, which is expected to be the largest individual solar PV project in the MENA region. It will boost the transformation of Saudi Arabia’s energy structure and its low-carbon development.[22]

China has also been supporting Saudi Arabia to diversify its economy and integration with the BRI. The Saudi government aims to reduce its dependence on oil and transform the country into a “leading industrial powerhouse and global trading and logistics hub.”[23]

In the UAE, the Emirates News Agency (WAM) reported that the country has contributed to and benefited from the BRI and will support its future economic development and prosperity. It has been a partner since 2013. The country’s economic and trade partnerships with China are extensive and diverse, as is the case with countries contributing to the commercial routes of the Silk Road. It is also a founding member of the AIIB.[24]

With its advanced logistics capabilities (ports and airports), the UAE can support the BRI’s land and maritime routes. Its involvement will enhance trade and infrastructure development and transportation projects and reduce investment costs. The UAE’s competencies and geostrategic location, supported by the BRI, will facilitate the achievement of its regional and international goals.[25] The WAM report indicated the following:

- The BRI can greatly enhance the UAE’s sources of competitive advantage and develop its foreign trade and re-export competence.

- The UAE has invested US$10 billion to support BRI projects in East Africa in collaboration with China.

- In 2018, the UAE signed 13 MoUs with China aimed at investments in the UAE.

- 88% of the UAE’s imports are from BRI partner countries, which receive 94% of its non-oil exports and 92% of its re-exports.

- In the first half of 2023, the UAE’s non-oil trade with BRI member countries reached US$305 billion, which is 90% of its non-oil trade.[26]

In September 2022, the UAE’s Minister of Energy and Infrastructure described the relationship between China and the UAE as becoming increasingly closer and characterized the relations between the two countries as having “broad development potential and positive prospects.” According to the Minister, the UAE contributed to more than 650 projects with Chinese investments, while over 4,000 Chinese companies were operating in the UAE at that time, creating more than 400,000 jobs.[27]

In November 2022, the UAE’s Ambassador to China stated that Silk Road e-commerce helped conventional foreign trade companies realize customized manufacturing. He also stated that the UAE was ready to develop bilateral relations through the BRI.[28]

Saudi Arabia hosted the China-GCC Summit in December 2022. The relationship between the two entities dates back to 1981, when the GCC was created. According to President Xi, China and the GCC have a history based on “solidarity, mutual assistance and win-win cooperation.” He described them as “natural partners of cooperation,” as China has a “vast consumer market and a complete industrial system, while the GCC, with rich energy and resources, is embracing diversified economic development.” Xi believes that China and the GCC should partner for greater solidarity, common development, common security, and cultural prosperity. He committed China to work with the GCC states over the period to 2027 on the following priorities:[29]

- Set up a new paradigm of all-dimensional energy cooperation. This will include China continuing to import crude oil on a long-term basis from the GCC and purchasing more LNG. He proposed, among others, that the Shanghai Petroleum and Natural Gas Exchange platform be used for RMB settlement in the oil and gas trade. In addition, the two parties will collaborate closely on clean energy projects and technologies and the local production of new energy equipment.

- Progress in finance and investment cooperation. China and the GCC could collaborate on financial regulation and facilitate GCC companies’ entry into China’s capital market. China will collaborate with the GCC in setting up a joint investment commission and support cooperation between their sovereign wealth funds. Specific projects could include currency swaps, digital currency cooperation, and advancing the m-CBDC Bridge project.

- Expand new areas of cooperation in innovation, science, and technology. China is ready to collaborate with GCC countries on building big data and cloud computing centers, innovation and entrepreneurship incubators, 5G and 6G technology, and implementing digital economy projects in areas such as e-commerce and communications networks.

- Seek new breakthroughs in aerospace cooperation. China will collaborate on infrastructure projects with the GCC on remote sensing, communications satellites, space utilization, and the aerospace sectors. This will include collaboration on developing astronauts, payloads for China’s aerospace missions, and establishing a China-GCC joint center for lunar and deep space exploration.

- Nurture new highlights in language and cultural cooperation. China will cooperate with 300 universities and schools in GCC countries on Chinese language education.

The above examples are not an exhaustive list of projects between China and the GCC. The GCC in general, and Saudi Arabia and the UAE in particular, are clearly heavily invested in the BRI. They contribute to its initiatives while also benefiting significantly from their participation in it.

Introducing IMEC

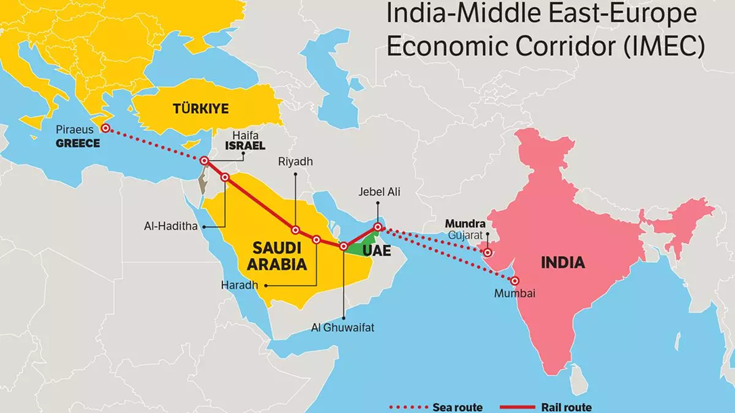

The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) is a collaborative initiative created on 9 September 2023 by the European Union (EU) and the governments of the United States of America, France, Germany, India, Italy, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.[30] IMEC will be approximately 4,800 kilometers long, with two separate wings and the Gulf countries in the center. The eastern maritime wing will connect India to the Middle East states of the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Israel, which will be connected by rail. The western or northern wing will connect the Gulf states to Europe (Greece) via shipping and rail.[31] See Figure 1 for a map of the IMEC.

The corridor’s transport infrastructure will “connect commercial hubs, facilitate clean energy export, lay undersea fiber-optic cables and pipelines for clean hydrogen, link energy grids and telecommunication lines to expand reliable access to electricity and improve cooperation in clean energy technology.” As such, the IMEC aims to boost trade flows in goods, energy, and services between India, the Middle East, and the EU.[32]

According to Matthee (2023), IMEC will complement the EU’s current initiative, the Global Gateway. The latter aims to build “strategic leverage, entrench economic partnerships, and promote European interests in crucial trade partners,” and has set aside €300 billion for infrastructure investments abroad between 2021 and 2027.[33]

Figure 1: Map of IMEC

Source: “India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor: A passage of possibilities,” Frontline, October 5, 2023, https://frontline.thehindu.com/world-affairs/how-the-india-middle-east-europe-economic-corridor-opens-up-a-passage-of-possibilities/article67344064.ece.

Matthee describes IMEC as a “helpful move to achieve de-risking,” or “the gradual rebalancing of trade and economic relations between the EU and China.” He believes it can be an alternative to, among other things, the BRI and describes it “as one of the pillars of Europe’s broader Indo-Pacific strategy.”[34]

For the EU, IMEC could support its stakeholders to promote their climate and renewable energy goals. In addition, the European Commission’s Economic Security Strategy states that managing risks to its supply chains and critical infrastructure, technology leakage, and the weaponization of the economic sector is important.[35]

The U.S. as driver of IMEC

It was U.S. President Joe Biden who announced the IMEC initiative at the G20 Summit in India in September 2023, stating that the IMEC “is expected to stimulate economic development through enhanced connectivity and economic integration across two continents, thus unlocking sustainable and inclusive economic growth.”[36]

Fuad Shahbazov, an international security expert, did not hesitate to describe IMEC as part of the West’s efforts to restrict the influence of the BRI and “prevent it from dominating trade between Europe and Asia.” He believes that while IMEC is unable to challenge the BRI in the short term, it could “revolutionize global trade dynamics” in the longer term. Shahbazov also believes that a successful IMEC could weaken Iran, and also improve the relationship between the U.S. and its allies.[37]

According to Shahbazov, the U.S. wants to use IMEC to transform the geoeconomics and geopolitics in the Middle East. It has had to deal with the fact that three of its allies in the Middle East, i.e., Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, became members of BRICS on 1 January 2024, thereby moving closer to both China and Russia. Saudi Arabia improved its relationship with Iran through the mediation of China.[38] This would not have gone off well with the U.S. Boosting IMEC would, therefore, support the U.S.’s endeavors to demonstrate its long-term commitments to its Gulf partners.

Shahbazov points out that IMEC provides several benefits to Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Among others, IMEC is aligned with Saudi Arabia’s “Vision 2030” for economic diversification. Shahbazov stated that the U.S.’s quest to get Saudi Arabia involved could be driven by its goal of normalizing relations between Saudi Arabia and Israel. He acknowledges that the Israel-Gaza war has severely damaged cooperation between Israel and the Arab world.[39]

The Asia Research Unit (ARU) of the Emirates Policy Center opines that for the U.S., IMEC is an element in its “comprehensive regional strategy to boost the confidence of GCC partners in Washington’s commitment to the region, isolate Iran, incorporate Israel in the regional order, enhance India’s status and influence in the region, and, first and foremost, confront China’s increasing influence in the region.”[40] It, therefore, agrees with Shahbazov, by seeing IMEC as a U.S. attempt to limit China’s influence in the region.

IMEC as an alternative to the BRI

There are contrasting views on whether IMEC is a competitor to the BRI. According to Matthee, China and India are in different positions regarding trade with the EU. Chinese companies are some of the largest suppliers of goods to the EU, and China is the continent’s second-largest trade partner after the U.S. (US$850 billion in 2022). India’s trade with the EU, in contrast, is much lower, at US$90 billion. It begs the question of why the EU would endanger such a significant trade relationship with China in favor of one with India. Should EU-based companies be compelled to abandon China, it would harm them and could cause them to leave the EU for elsewhere, while also weakening Europe’s economy. However, this question is only relevant should one see the situation as a zero-sum game, with the EU being forced to either trade with China or India, which is definitely not the case.[41] It must be admitted, though, that the balance of trade between China and the EU is heavily in China’s favor.

Matthee believes that while IMEC offers EU countries an “opportunity to enhance economic ties and serve their geopolitical interests,” the various countries have different strategic interests. For example, he states that France’s defense industry links with Gulf countries would be different from Germany’s, while Italy would be more concerned about enhancing its maritime interests than Germany would. To increase the complexity of IMEC, the Israel-Hamas conflict has led to major internal differences in the EU institutions and national ministries and even casts doubts on the viability of IMEC should Israel remain in the equation.[42]

Compared directly with the BRI, IMEC’s scope is narrower. The governments involved view it as an instrument to grow economic partnerships and increase their influence. However, IMEC faces challenges such as integrating its transport modes and managing diverse stakeholders. Despite having several land and sea connections, it lacks the scale of required highways and railways and must deal with difficult geography—mountains in Greece and deserts in the GCC. Moving goods and services along the IMEC corridor must also deal with challenges such as diverse customs procedures, legal systems, policies and regulations, transportation protocols, and taxation.[43] In addition, Matthee points out that it is not known whether the region’s trade volume would be sufficient to support both the IMEC and the BRI. Potential private investors may also be hesitant to invest, as they could perceive it as too costly and difficult.[44]

Matthee makes an interesting point when he refers to the “increased power of medium-sized powers and their choice not to align with the United States or Russia in the Ukraine war.” He views IMEC as an attempt by “the EU to provide infrastructure investments in partnership with non-Western actors.” The implementation of IMEC would help EU governments to expand their economic interests in the Gulf, while “the Gulf would become even more important as a hub between Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.”[45] It can also be seen as an attempt by the EU to reduce any economic dependence it might have on the U.S.

Matthee believes that Europe’s existing political and security relationships with the Gulf region will remain significant, irrespective of what happens with IMEC. A successful IMEC, however, could cause more active intelligence collaboration and security cooperation with the Gulf region.[46]

If implemented, IMEC would increase Europe’s influence alongside China’s. In its interaction with the EU, Matthee believes Gulf countries could pursue IMEC as an open-ended platform and provide them with more options for their economic and geopolitical strategies.[47]

The ARU analyzed whether IMEC was indeed to compete with the BRI. Trade between India and the GCC has improved significantly, growing from US$87.4 billion in 2021 to US$184 billion in 2022/2023. The UAE and India’s trade amounted to US$84.5 billion by March 2023, while Saudi Arabia and India pledged to speed up the Saudi investment program in India by US$100 billion. Similarly, the GCC’s trade with the EU also increased to US$186 billion in 2022.[48]

As was their response when India and Japan launched the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC) in 2016, China responded to the IMEC by commenting that global infrastructure initiatives should cooperate and not compete. The ARU believes that “the IMEC may not directly threaten the more stable, deep, mature, and vast BRI. Instead, it might, if achieved, turn into a parallel and complementary initiative, not an alternative one.” China stated that the IMEC overlaps with the BRI’s projects at several central logistical points, such as India’s ports, the UAE’s Khalifa Port, Haifa Bayport, the Greek port of Piraeus, and the Greek rail company Piraeus Europe Asia Rail Logistics (PEARL), which moves goods from Piraeus Port to all of Europe and Asian countries. Chinese corporations have a shareholding in either the port infrastructure or the railway lines connecting the various countries. BRI and IMEC projects are, therefore, interdependent. According to the ARU, “IMEC enhances direct gains by Chinese firms working in these strategic points. This implies that China and the BRI might be IMEC’s biggest beneficiaries.”[49]

The ARU also identified potential opportunities for China to expand logistical, technical, and energy projects with countries whose interests might be undermined by IMEC’s implementation, including Egypt and Turkey. Egypt’s revenue potential might be negatively affected by the IMEC taking transportation away from the Suez Canal, an important revenue generator for Egypt. Turkey’s President Erdogan stated, “There is no corridor without Turkey.” Erdogan identified the Development Road Project that would connect the Gulf region with Turkey and Europe through a railway that passes through Iraq. Chinese companies could take advantage of the emerging skepticism about the IMEC and sign additional agreements as part of the BRI.[50]

According to the ARU, the neutral stakeholders in IMEC who wish to remain non-aligned between China and the West, i.e., the UAE and Saudi Arabia, would prefer an integration between the two initiatives. India, on the other hand, has been feeling “strategically and geo-economically surrounded by China.” It has also felt threatened by China’s growing influence in the Gulf. IMEC, therefore, represents an opportunity for India to address its geo-economic and geopolitical situation.[51]

According to Barnes-Dacey and Bianco (2023), the Gulf has embraced “global multipolarity.” While IMEC can improve Western economic influence and stabilize economic growth, “it will not, however, be a vehicle to pull regional powers away from Beijing.” They point out that the Gulf states see IMEC “within the context of a new global order in which they can balance ties with both China and the West to maximize their own gains.” According to these authors, Saudi Arabia and the UAE do not share the concerns of Europe and the U.S. about “the vulnerabilities of economic dependence on China and energy ties to Russia.” Instead, they have identified the opportunity to serve as global hubs, given their location and reach into Africa, Asia, and Europe. The authors believe that the Gulf states will grasp opportunities to enhance their connectivity and, as such, “increase their own reliance on fully globalised supply chains.” Given this, IMEC will align rather than compete with the BRI, with Saudi Arabia and the UAE perceiving it in their interest to work with both.[52]

The Gulf states have strong ties with China and Russia. China is reportedly the largest single buyer of GCC oil and gas. Barnes-Dacey and Bianco point out that Huawei, which is strongly mistrusted by the West, has a dominant position in the GCC market for digital infrastructure. In addition, China has interests in several regional ports, for example in Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.[53]

Conclusions

The remarkable growth and success of the BRI, despite its slowdown during the COVID-19 pandemic era, makes it an attractive option to support. The huge growth in trade, infrastructure (road, rail, ports, airports), and social initiatives (health, culture, education, and digital) for the BRI partners is a clear indication of the progress that has been achieved.

Arguments that a successful IMEC could weaken Iran and also improve the relations of the U.S. with its allies are not strong arguments. Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have become members of the BRICS, dominated by China. Iran is also a beneficiary of the BRI and enjoys support from China and Russia. China has also facilitated the rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

While Saudi Arabia and the UAE are willing to develop sound relations with Europe and the U.S., they are not willing to limit their relations with China and Russia. They have also already committed to a large number of projects in the BRI. IMEC membership will not move the GCC states away from China or Russia.

It is clear that Saudi Arabia and the UAE will benefit from their involvement in not only the BRI but also in IMEC. There is no downside for them in their relations with China as China itself would be a significant beneficiary of IMEC’s success. IMEC is, therefore, as far as the GCC is concerned, not a competitor to China’s BRI.

The GCC’s involvement in IMEC would also not only not affect their relations with China negatively, but would, in contrast, positively impact these relations that have already been bolstered by their involvement in the BRI and BRICS. The potential growing rapprochement between the EU and China, as seen during the very recent visit of President Xi Jinping, will also benefit Saudi Arabia and the UAE, as well as the other members of the GCC. What is good for China, is good for the GCC, if not economically, then strategically.

Given Saudi Arabia’s and the UAE’s extensive involvement in the BRI, as well as the rest of the GCC, it is highly unlikely that the GCC countries targeted for involvement in IMEC would leave the BRI to join IMEC, were that a requirement. It is unthinkable that the GCC states will abandon the BRI for IMEC. Both initiatives are aligned with Qatar and Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 of economic diversification and serve the same purpose for the other GCC states.

Therefore, those who propagate IMEC as an initiative to curb the influence and impact of China’s BRI by roping in Saudi Arabia and the UAE have made a strategic miscalculation. Membership of the BRI, IMEC, and BRICS is a win-win for the GCC countries involved.

Therefore, the GCC members find themselves in a wonderful win-win situation. They benefit from the BRI and will also benefit from IMEC, should the latter eventually manifest. This situation where the GCC states are actively wooed to become members of the various geoeconomic and geopolitical groupings works in their favor and might even embolden them to demand greater commitments from the initiators of these groupings.

Should IMEC lead to resistance from Turkey with the latter developing its Development Road Project in collaboration with the Gulf states, China could benefit from this, and conclude agreements as part of the BRI. This would provide the GCC with additional avenues of revenue and benefits.

China could also benefit from Egypt’s resistance to IMEC by increasing its investments in Egypt in, amongst others, the Suez Canal Free Zone. Egypt’s membership in BRICS and existing Chinese investments in the country make such a possibility quite likely. China is already the largest investor in Egypt’s Suez Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone.

The potential investments in Turkey and Egypt would increase China’s strategic influence in the Middle East, which would benefit the GCC as well.

President Xi Jinping’s visit to Europe in May 2024 may not have been successful for France in addressing its trade issues. However, their views on support for the development of a multipolar world are aligned, an ideology embraced by, among others, the GCC states. The development of Hungary as a beachhead in Europe could benefit China and its BRI. Whatever benefits the BRI vis-a-vis Europe would benefit the GCC states. Economically, China’s success or lack thereof in the EU would not meaningfully affect the GCC. However, China’s success in gaining EU support for a multipolar world will have a meaningful impact on the GCC.

One should not see the GCC states as preparing to choose between supporting either China or the U.S. at the cost of the loser. It has embraced the adoption of a multipolar dispensation and is comfortable working with all the global parties, such as China, the U.S., and the EU.

The ARU’s perspective that IMEC could potentially become a complementary initiative if it is successful is valid. It is also correct to state that IMEC is not a direct threat to the much larger BRI. So are its views that China and the BRI might be IMEC’s biggest beneficiaries

Barnes-Dacey and Bianco’s view that the GCC will not be beholden to either the U.S. or China is also valid. As they state, the GCC will wish to see the IMEC and the BRI as complementing each other, and they will support the initiatives that drive multipolarity and their economic well-being. Indeed, IMEC will significantly increase the Gulf region’s already huge strategic importance in the future. It is already an important hub for the world’s large players, such as China, the EU, India, Japan, Russia, and the U.S.

The final message is that whatever is good for China is good for the GCC. The BRI is good for China, the IMEC is good for China, Turkey’s Development Road Project is good for China, and investments in Egypt are good for China. Therefore, all of these are good for the GCC.

[1] D. Yong, “The Belt and Road Initiative: The New Silk Road to the Chinese World Order,” RSIS Seminar, Nanyang Technological University, July 25, 2017.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Deepankar Banerjee, “China’s One Belt One Road Initiative — An Indian Perspective,” Yusof Ishak Institue, March 31, 2016, https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/ISEAS_Perspective_2016_14.pdf.

[4] Lauren A. Johnston, “Africa’s and China’s One belt One Road initiative: Why now and What next?,” International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, September 15, 2016, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316194863_Africa_and_China’s_One_Belt_One_Road_initiative_Why_now_and_what_next.; D. Yong, “The Belt and Road Initiative: The New Silk Road to the Chinese World Order,” op.cit.

[5] Alicia Garcia-Herrerro and Robin Schindowski, “Global trends in countries’ perceptions of the Belt and Road Initiative,” Bruegel, April 25, 2023, https://www.bruegel.org/working-paper/global-trends-countries-perceptions-belt-and-road-initiative.

[6] The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, “Full text: The Belt and Road Initiative: A Key Pillar of the Global Community of Shared Future,” October 10, 2023, https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/whitepaper/202310/10/content_WS6524b55fc6d0868f4e8e014c.html.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] British Council, “China’s Third Belt and Road Forum,” October 26, 2023, https://opportunities-insight.britishcouncil.org/news/news/china’s-third-belt-and-road-forum.

[10] The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, “Full text: The Belt and Road Initiative: A Key Pillar of the Global Community of Shared Future,” op. cit.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Christoph Nedopil, “China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): Investment Report 2023, Griffith Aisa Institute, Griffith University, February 2024, https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0033/1910697/Nedopil-2024-China-Belt-Road-Initiative-Investment-report.pdf.

[16] Belt and Road Portal, “Full text of Xi’s signed article on Saudi media,” December 8, 2022, https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/295294.html.

[17] The State Council; The People’s Republic of China, “Full text: The Belt and Road Initiative: A Key Pillar of the Global Community of Shared Future,” op. cit.

[18] Christoph Nedopil, “China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): Investment Report 2023,” op. cit.

[19] The World Bank, “Belt and Road Economics: Opportunities and Risks of Transport Corridors,” June 18, 2019, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/regional-integration/publication/belt-and-road-economics-opportunities-and-risks-of-transport-corridors.

[20] Zawya BRI Focus: A New Narrative, https://api.zawya.atexcloud.io/file-delivery-service/version/c:ZDQ0MTA0ZWYtZjcwMi00:ZWYtZjcwMi00ZDY3NzFk/ZAWYA-BRI-Focus-Issue-3-6.pdf.

[21] Mercy A. Kuo, “China-Russia Cooperation in Africa and the Middle East,” The Diplomat, April 3, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/04/china-russia-cooperation-in-africa-and-the-middle-east/.

[22] NDRC, People’s Republic of China, “Belt & Road fits well with nations’ growth strategies,” December 30, 2022, https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/netcoo/goingout/202212/t20221230_1346105.html.

[23] Ibid.

[24] “UAE celebrates 10 years of BRI, maintains focus on development,” China Daily, October 20, 2023, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202310/20/WS6531e8dfa31090682a5e9bc0.html.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] NDRC, People’s Republic of China, “BRI projects connect the world and improve livelihoods, forum hears,” September 29, 2022, https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/news/mediarusources/202210/t20221008_1338358.html.

[28] NDRC, People’s Republic of China, “Silk Road e-commerce boosts two-way trade between China, countries along BRI route,” November 3, 2022, https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/news/mediarusources/202211/t20221103_1340809.html.

[29] Belt and Road Portal, “Full text of Xi Jinping’s keynote speech at China-GCC Summit,” December 10, 2022, https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/295963.html.

[30] Heinrich Matthee, “The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor Beyond Transactional Opportunites,” Emirates Policy Center, November 28, 2023, https://epc.ae/en/details/featured/the-india-middle-east-europe-economic-corridor-beyond-transactional-opportunities.

[31] Fuad Shahbazov, “Reimagining Geopolitics: How the IMEC Corridor Aims to Reshape Global Trade Dynamics,” Gulf International Forum, 2023, https://gulfif.org/reimagining-geopolitics-how-the-imec-corridor-aims-to-reshape-global-trade-dynamics/.

[32] Asia Research Unit, “IMEC and BRI: Beyond Complementary Competition,” Emirates Policy Center, October 20, 2023, https://epc.ae/en/details/scenario/imec-and-bri-beyond-complementary-competition

[33] Heinrich Matthee, “The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor Beyond Transactional Opportunites,” op. cit.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Asia Research Unit, “IMEC and BRI: Beyond Complementary Competition,” op. cit.

[37] Fuad Shahbazov, “Reimagining Geopolitics: How the IMEC Corridor Aims to Reshape Global Trade Dynamics,” op. cit.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Asia Research Unit, “IMEC and BRI: Beyond Complementary Competition,” op. cit.

[41] Heinrich Matthee, “The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor Beyond Transactional Opportunites,” op. cit.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Asia Research Unit, “IMEC and BRI: Beyond Complementary Competition,” op. cit.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Julien Barnes-Dacey and Cinzia Bianco, “Intersections of Influence: IMEC and Europe’s role in a multipolar Middle East,” European Council on Foreign Relations, September 15, 2023, https://ecfr.eu/article/intersections-of-influence-imec-and-europes-role-in-a-multipolar-middle-east/.

[53] Ibid.