2023: The Hottest Year on Record

In July this year, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres raised alarm when he stated, “Climate change is here. It is terrifying. And it is just the beginning. The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived.”[i] Calling for swift climate action, the secretary-general added that “the extreme impacts of climate change have been in line with scientists’ “predictions and repeated warnings”, and that the “only surprise is the speed of the change.”[ii] Indeed, climate scientists believe July 2023 was the hottest month in 120,000 years, with over 10,000 records of temperature and rainfall broken globally.[iii] In 2015, world leaders established a goal of restricting the maximum increase in the average global temperature to 1.5 degree Celsius above preindustrial global temperatures as a crucial ceiling to avoid climate catastrophe; however, in July, the average global temperature breached that level, albeit briefly. Clearly, 2023 is on track to be the hottest year on record ever. What does this mean for the world and how does it impact the Middle East region? This article examines the likely impact of these changes globally in general and in the Middle East in particular and discusses what could be the way ahead.

The impact of the rapid increase in global temperatures is already being seen in the form of unprecedented natural or climatic disasters such as bigger floods, widespread droughts, intense cyclones and frequent massive forest fires in regions where they were almost unheard of. For instance, in Europe the extreme heat this summer led to hundreds of wildfires in Greece. While many of these fires were put out quickly, some spread out of control, such as the one in the Alexandroupolis and Evros regions of northeastern Greece — near the border with Turkey — which reportedly was the biggest the European Union has ever recorded, claiming over 20 lives.[iv] According to the European Union-backed Copernicus Climate Change Service, firefighters from five countries battled to contain the fire that lasted 11 days and destroyed over 800 square kilometers of forest land — an area larger than New York City![v] Greece was not the only location to witness such fires; earlier in the year, wildfires in Canada razed territory equal to the size of Greece! In another event, temperatures in excess of 51 degrees Celsius recorded in parts of southern Iran forced the government to declare a two-day public holiday, advising people to stay indoors.[vi]

Higher temperatures recorded globally means that the warmer atmosphere can now hold and deliver greater precipitation. This explains the recently recorded heavy rains causing widespread destruction in many cities. For instance, in July, Beijing saw the heaviest rains in 140 years, bringing the city to a halt. About 31,000 people had to be evacuated from their homes and almost 20,000 buildings were inspected for damage while both airports in the capital cancelled more than 200 flights.[vii] During the same time, heavy rains resulted in massive floods in northern India, with New Delhi recording its ‘wettest July day in more than 40 years,’[viii] according to authorities and local reports. The rains also triggered flash floods and landslides, killing at least 22 people, mostly in the northern state of Himachal Pradesh. The same warm and wet conditions in the entire region in Asia also precipitated the worst ever outbreak of Dengue fever in Bangladesh that reportedly killed over 1,000 people and infected over 208,000, overwhelming the country’s healthcare system.[ix]

The above list of climatic disasters is not exhaustive and includes various other recent disasters, such as the major floods in New York that cost the city about $19 billion in damages[x] and the September floods in Libya. Overall, it is clear that extreme climatic events are becoming more intense and frequent. And many of these events, once regarded as once-in-a-lifetime occurrences, are now recurring annually. Although major climatic disasters have occurred in various places globally, they have rarely been reported from the same places repeatedly. For instance, a major heat wave in Europe last happened 500 years ago. Floods in New York were reported once in 250 years.[xi] Furthermore, in the United States, the number of billion-dollar disasters has increased from two in 2002 to 18 in 2022 and 15 until July 2023. As global temperatures rise, the chances that extreme climatic events will recur at the same location are growing rapidly. It is likely that by 2050, many countries will experience flood levels annually that until recently were seen once in a century.[xii] Seeing these as isolated incidents or ‘freak events’ does not fully explain the situation because when natural disasters occur in the same area again and again and more frequently, the combined effects of such events can often be greater than the sum of their parts. For instance, repeated droughts in Syria precipitated a collapse of the economy leading to a political crisis. This is discussed later in the article.

Approaching a New Normal

It seems that a new normal for the climate has been established and we now need to adapt to it, particularly in the cities where more than half of the world’s population or about 4.3 billion people live. Pertinently, in the Middle East more than 80 percent of the population now lives in urban areas.[xiii] Accordingly, governments must now focus on adjusting to the new reality by upgrading infrastructure to withstand extreme weather, else the ongoing scale of climate related disasters could cause widespread damage. Already, as described above, the intensity and frequency of climate related disasters in major cities across the world such as New York, Beijing and New Delhi seems to have overwhelmed existing infrastructure efforts. While countries with poor infrastructure are likely to be impacted the most, even the ‘best prepared’ countries in the world do not seem to be ready to face climate change in the twenty-first century. Take, for instance, the Netherlands. Geographically, one-third of the country is located below sea level, with the lowest point being 6.7 meters below sea level. Yet the country has not just survived floods but continues to flourish thanks to the world’s most advanced and extensive system of dikes, pumps and artificial embankments along the coast. But in July 2006, the country witnessed its warmest month ever in its history, resulting in about 1,000 fatalities.[xiv] Since then, the Netherlands has faced several heat waves, with several deaths being reported. Evidently, no country in the world is prepared for all the vagaries of climate change.

Reaching Tipping Points

According to climate scientists, our greatest worry is about reaching ‘tipping points’ or potential rapid disruptive effects that could trigger massive impacts. For instance, the melting of ice in Greenland alone could rapidly raise sea level up to six meters, eventually ‘drowning Miami and Manhattan and London and Shanghai and Bangkok and Mumbai.’[xv] Pertinently, Greenland is already losing almost a billion tons of ice daily. Since 2014, scientists believe Greenland and the Antarctic are more vulnerable to melting than previously known, and perhaps a tipping point has been reached with respect to the ice sheets in Western Antarctic more than doubling its ice loss in five years. According to Peter Brannen, an award-winning science journalist, the last time the earth was four degrees warmer, there was no ice at either pole and sea level was 260 feet higher![xvi]

The other tipping point could be the melting of the Arctic permafrost, which could lead to the release of large amounts of greenhouse gases that include methane and carbon dioxide, which could further accelerate global warming. Significantly, methane is far more dangerous as a GHG than carbon dioxide. Evidently, atmospheric levels of methane have risen significantly in recent years, and a new study reveals that by 2100, the Arctic will have released a hundred billion tons of carbon, which is the ‘equivalent of half of all the carbon produced by humanity since industrialization began.’[xvii] Finally, rising global temperatures could even lead to the reversal of the Gulf Stream, a warm current flowing from the Equatorial region to the middle latitudes in the Atlantic Ocean. The Gulf Stream acts as a great circulatory system that essentially regulates and modulates the temperature of the planet. How does this work? The waters of the Gulf Stream cool off in the atmosphere of the Norwegian Sea, making the water itself denser, which sends it down into the bottom of the ocean. This body of water is then pushed southward by more Gulf Stream water and melting ice from Greenland falling to the ocean floor, replaced by warm currents flowing from the Equatorial region; the entire trip can take a thousand years. A reversal of the Gulf Stream could be catastrophic for large parts of Europe and North America, as it could lower temperatures by up to 10 or 15 degrees in Europe and lead to rising sea levels in the eastern U.S.[xviii] While precise tipping points are not yet known, scientists believe these are not very far. The greatest worry is that each of these points could lead to a ripple or cascading effect. For example, the melting of ice in Greenland could dilute the salinity of the Atlantic Ocean, which could hasten the reversal of the Gulf Stream. Clearly, there is a sense that the window to respond to or adapt to these threats is small and that calls for urgent action by all countries.

Based on the above, it is evident that the world is now entering a ‘dangerous phase’ in climate change. The question is: how does it impact the MENA region, which is already among the planet’s hottest and driest regions? According to climate forecasts, a ‘business-as-usual’ approach to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions could lead to average global temperatures rising by over 4 degrees Celsius by 2100.’[xix] However, since temperature changes are unevenly distributed around the planet, with some regions experiencing more warming than others, experts warn that the MENA region could be subjected to a temperature rise of up to 4 degrees Celsius by 2050 and up to 7 degrees Celsius by the end of the century. Already, a visible pattern of climatic distress can be seen emerging across the MENA region revealing inherent vulnerabilities in certain countries, particularly the poorer states with an agrarian economy as compared to the oil-rich states of the region. For example, in 2020, heavy floods affected Egypt, Iran and Tunisia while in the same year, wildfires spread in Lebanon, Syria and Turkeye. The next summer brought a crippling drought in Iraq and Syria – its worst in 70 years. It really can’t be a coincidence that many of these countries are also facing internal political turmoil. For instance, Syria spiraled into civil war in 2011, following a major drought from 2006 to 2010, which triggered a collapse of the agricultural economy, resulting in the mass migration of millions of refugees across the region.[xx] Manifestly, repeated climatic disasters in the same place have a multiplier effect making a bad situation worse as noted by the U.S. president Barack Obama who stated: “Climate change helped fuel the early unrest in Syria, which descended into civil war.”

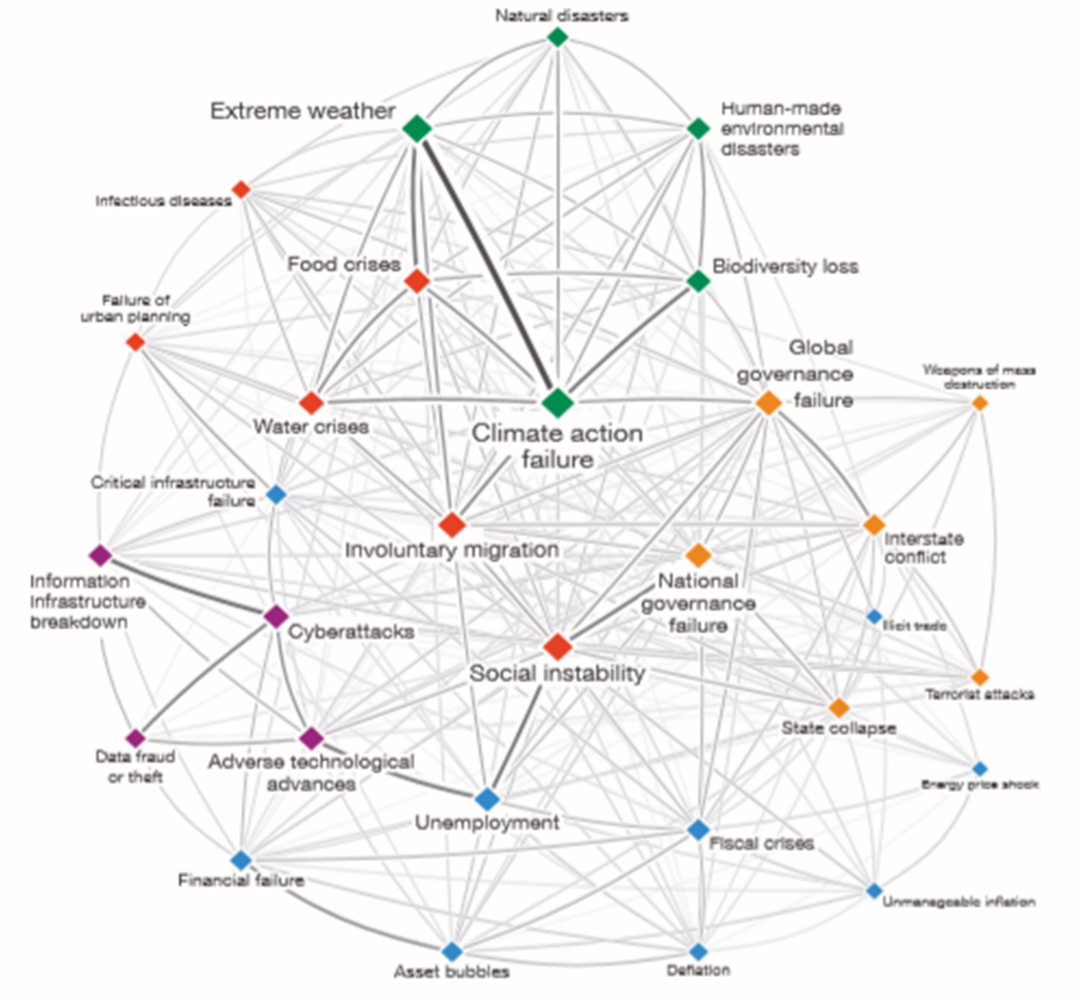

Evidently, there is a link between climate change and security. According to the World Economic Forum report on global risks, climate action failure can lead to extreme weather events that could cause food and water shortages, leading to mass migrations, which would potentially lead to interstate border conflicts, and so on. The following chart shows how each threat is closely related.

Source: World Economic Forum Global Risks Report 2021

Many of the inter-connected effects of extreme climatic conditions such as high temperatures, floods and droughts/desertification leading to water and food shortage have been seen in the Middle East region. For instance, in addition to the case of Syria discussed above, the largest country in the region, Saudi Arabia is now considered as one of the most water-scarce countries globally, with its ‘per capita water demand levels double the global average at 265 liters per day.’ Furthermore, the country is also dependent on imports for 80 percent of its food supplies[xxi] and could potentially face a total collapse of its miniscule food production by 2050 if the current forecasts about extreme climatic conditions come true.

The situation in other neighboring countries in the Arabian Peninsula is similar; however, there is a stark difference in terms of overall resilience, with the UAE and Saudi Arabia being far better prepared to deal with climate change than the other financially constrained regional states such as Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Yemen. The latest ongoing conflict involving the Hamas and Israel has added to the woes of the region. Clearly, investing in climate action policies is a luxury many regional states can barely afford at this stage.

However, in stark comparison, both Saudi Arabia and the UAE seem to be better prepared and on track to adapt to the ‘new climatic normal.’ This is evident from the futuristic infrastructure development in these countries as also government plans and policies. For instance, in 2021, Saudi Arabia launched the Saudi Green Initiative (SGI) under its Vision 2030 program that was initially announced in 2016. Under the SGI, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has taken decisive steps towards a more sustainable future by “uniting environmental protection, energy transition and sustainability programs” with the overarching aims of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and increasing the Kingdom’s use of clean energy.[xxii] Under the SGI, Saudi Arabia will invest over $186 billion in various projects aimed at reducing emissions, afforestation, and land and sea protection. This includes a commitment to rehabilitate 40 million hectares of land by planting a staggering 10 billion trees across Saudi Arabia. Additionally, in November 2022, Saudi Arabia committed $2.5 billion to establish a Middle East Green Initiative (MGI) as a regional effort to mitigate the impact of climate change in the wider Middle East region.[xxiii] The MGI broadly aims to increase regional cooperation by creating the necessary infrastructure required to reduce GHG emissions and protect the environment. One of the several ambitious projects includes planting of 40 billion trees across the region beyond Saudi Arabia. However, given the extant security situation across the region and the weak economic standing of many regional states, practical implementation of the project could present hurdles. Furthermore, considering the overall scale of the challenge in the wider region, perhaps a larger fund under the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) could be considered to sustain climate action in the long term.

One of the best-prepared countries in the MENA region could probably be the UAE, which, under its National Climate Change Plan 2017-2050, is committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 — the first Middle East state to hit this target.[xxiv] Broadly, the UAE climate change plan aims to achieve an improved scientific GHG emissions management system, adapt to the changes in climate by building resilience through infrastructure and other risk mitigation efforts, and finally diversify the country’s economy towards green businesses.[xxv] Evidently, both the UAE and Saudi Arabia have robust plans to develop resilient infrastructure to adapt to the new climatic conditions of the region. This is evident from the mushrooming of smart, sustainable Green cities across the region such as Masdar in the UAE and the Neom City in Saudi Arabia to name a few.[xxvi] Such futuristically planned cities that incorporate a number of efficiency measures in building design and landscape architecture seem to be suitably adapted to the new normal in climate. After all, if man can aspire to build colonies on Mars or the Moon with far more hostile conditions, we can certainly adjust to the new climatic normal with improved infrastructure for hotter and drier conditions. For instance, emerging geoengineering technologies such as cloud-seeding can potentially help overcome drought-like conditions. The UAE has been at the forefront of cloud seeding for decades to provide additional rainfall that could support agriculture and help deal with water security concerns. The Emirates conducts hundreds of rain cloud seeding missions each year, which have reportedly helped boost rainfall by up to 25 percent.[xxvii] But clearly, this is an expensive technology that few countries of the region can afford.

The Road Ahead

As highlighted by the UN Secretary-General, the world is indeed entering a ‘dangerous phase’ in climate change, and much earlier than previously anticipated. This means that the time to prepare or adapt to such changes is limited. Based on a study of recent climatic events/disasters across various global capitals, including Beijing, New York and New Delhi, we can expect life in many cities of the world to be frequently disrupted by heavy rains and heat wave conditions. Potentially, this could have a major impact in the Middle East region, where about 80 percent of people live in urban cities. Already, the impact of these changes is being felt in many parts of the region, albeit differently in the several states that have varying degrees of vulnerability, with Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon being among the worst hit. In the long term, this could hypothetically lead to widespread food and water shortages and mass migrations, patterns of which are currently seen in the region.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE stand out as some of the better prepared countries with robust plans to limit their GHG emissions and build resilient and smart cities. Saudi Arabia deserves credit for the launch of region-wide initiative such as the MGI. However, its success would depend upon the long term sustained efforts of the regional states, which seems to be lacking given their more pressing security and financial concerns. Perhaps the creation of a climate action fund under the GCC could greatly help to sustain climate action in the region in the long term. Overall, it seems that countries struggling to cope with political instability and security crises will continue to remain vulnerable to climate change — if anything, the ongoing Israel-Gaza war could potentially make matters worse. Other countries, like the UAE and Saudi Arabia, are expected to emerge as more resilient to the climatic disruptions. However, in the long term, even better-prepared countries cannot be immune to the overall impact of climate change and more needs to be done.

[i] “UN chief says Earth in ‘era of global boiling’, calls for radical action,” Al Jazeera, July 27, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/7/27/un-chief-says-earth-in-era-of-global-boiling-calls-for-radical-action.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Alice Hill, “The Age of Climate Disaster is here,” Foreign Affairs, August 25, 2023.

[iv] “Wildfire in northeastern Greece is the biggest the EU has ever recorded,” Euronews, August 30, 2023, https://www.euronews.com/2023/08/30/wildfire-in-northeastern-greece-is-the-biggest-the-eu-has-ever-recorded.

[v] “Greece wildfire destroys area bigger than New York City, Stamos Prousalis and Karolina Tagaris,” Reuters, August 29, 2023,

[vi] “Iran orders two days of public holidays over ‘unprecedented heat,’” CNN, August 2, 2023, https://edition.cnn.com/2023/08/02/asia/iran-heat-wave-shut-down-climate-intl/index.html.

[vii] Liz Lee and Ethan Wang, “Extreme rain in Beijing after typhoon turns roads into rivers, kills two,” Reuters,

July 31, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/typhoon-doksuri-thousands-flee-their-homes-heavy-rain-lashes-beijing-2023-07-31/.

[viii] Tara Subramaniam, Manveena Suri, “New Delhi records wettest July day in decades as deadly floods hit northern India,” CNN, July 10, 2023, https://edition.cnn.com/2023/07/10/india/india-delhi-wettest-day-flood-deaths-intl-hnk/index.html.

[ix] Helen Rega, “Bangladesh’s worst ever dengue outbreak has now killed more than 1,000 people,” CNN, October 3, 2023, https://edition.cnn.com/2023/10/03/asia/bangladesh-dengue-fever-1000-deaths-intl-hnk-climate/index.html

[x] Denise Chow and Evan Bush, “Climate change and NYC: Historic rains buckle city’s infrastructure, again,” NBC News, September 30, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/science/environment/nyc-flooding-climate-change-infrastructure-limitations-rcna118170.

[xi] Michael Oppenheimer, “As the World Burns,” Foreign Affairs, October 13, 2020.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser, “Our World in Data,” Urbanization, October 31, 2023, https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization#:~:text=UN%20estimates%3A%2055%25%20of%20people%20live%20in%20urban%20areas&text=Figures%20reported%20from%20the%20United,extending%20from%201960%20to%202020.

[xiv] Istiaque Ahmed, Marjolein van Esch, Frank van der Hoeven, “Heatwave vulnerability across different spatial scales: Insights from the Dutch built environment,” Urban Climate 51, September 2023, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212095523002080.

[xv] David Wallace-Wells, The Uninhabitable Earth, (New York: Duggan Books, 2019) p. 62.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Ibid, p. 63.

[xviii] Georgina Rannard,”Will the Gulf Stream really collapse by 2025?,” BBC, July 26, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-66289494#:~:text=If%20it%20collapses%2C%20it%20could,115%2C000%20to%2012%2C000%20years%20ago.

[xix] David Wallace-Wells, The Uninhabitable Earth, op. cit., p. 62.

[xx] Marwa Daoudy, “Scorched Earth,” Foreign Affairs, February 22, 2022.

[xxi] Frederic Wehrey, “Climate Change and Vulnerability in the Middle East,” July 6, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/07/06/climate-change-and-vulnerability-in-middle-east-pub-90089#:~:text=The%20region’s%20temperatures%20are%20already,the%20end%20of%20this%20century.

[xxii] “SGI: steering Saudi Arabia towards a green future,” October 31, 2023, https://www.greeninitiatives.gov.sa/about-sgi/.

[xxiii] “MGI: powering regional climate action,” October 31, 2023, https://www.greeninitiatives.gov.sa/about-mgi.

[xxiv] “The UAE’s response to climate change,” October 29, 2023, https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/environment-and-energy/climate-change/theuaesresponsetoclimatechange#:~:text=The%20UAE%20supports%20green%20infrastructure,loans%20for%20clean%20energy%20projects.

[xxv] UAE Ministry of Climate Change and Environment, “National Climate Change Plan of the United Arab Emirates 2017-2050,” https://www.moccae.gov.ae/assets/30e58e2e/national-climate-change-plan-for-the-united-arab-emirates-2017-2050.aspx P. 24.

[xxvi] Ibid, p. 50.

[xxvii] “UAE: New cloud-seeding campaign effect? Heavy rains hit parts of country,” Khaleej Times, September 7, 2023, https://www.khaleejtimes.com/uae/weather/uae-new-cloud-seeding-campaign-effect-heavy-rains-hit-parts-of-country.