Central Asia is considered to be one of the world’s most vulnerable regions to a serious water scarcity threat. This threat to the region’s water security has been weighing on achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which most countries have set for 2030, as water plays a significant role in people’s livelihood, agriculture, and energy. A decline in water levels in dams and hydroelectric plants means a decrease in the production of electrical energy and is thus a major threat to every sector. This goes to show how critical water is and how grave a threat water scarcity is. The World Economic Forum’s Risk Report has listed water crises as one of the top 5 risks in terms of impact for the last eight years.[1] In addition, Ismail Serageldin, a former vice president of the World Bank, once said: “In the 20th century, individuals fought for oil; in the 21st century, they will fight for water”. This insight will shed light on the history of the conflict, the water interests of Azerbaijan and Armenia, and the countries that got involved in the conflict. It will also discuss current developments.

Brief history and origin of the conflict in the region

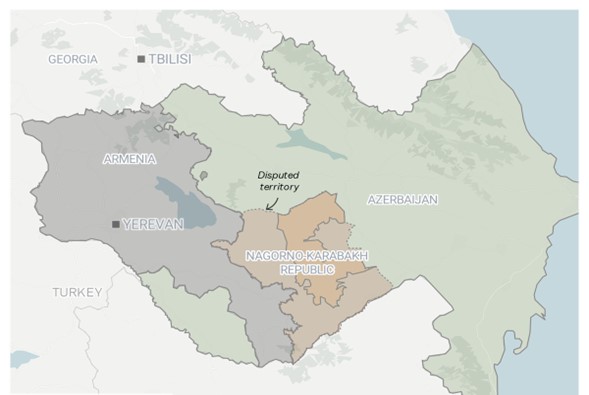

In Central Asia, on the border south of the Caucus Mountains, lies the longest conflict since the fall of the Soviet Union. The Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast was created by the Soviet Union in 1923. This was home to a majority of ethnically identified Armenians in the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic. In 1988, Nagorno-Karabakh’s regional legislature passed a resolution to declare its interest in joining the Republic of Armenia, even though it was officially located in Azerbaijan. This resulted in armed conflicts between the two republics, which have had a long history of ethnic tension.[2] In addition, the Soviet Union couldn’t be indifferent to such resolutions and votes and was known to be unresponsive to people’s calls for liberation or votes, so it remained a part of Azerbaijan as a semiautonomous territory. In 1991, after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, conflicts erupted between Azerbaijan and Armenia over the region that was formerly known as the Republic of Artsakh, “Nagorno Karabakh Republic” (NKR). Along with the statehood of Armenia and Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh also declared its independence, leading to a full-scale war.[3]

(Source: Tim Ryan Williams/Vox, 2020)

At least 1 million people were displaced and forced to flee from their homes and villages that were on the borders of both republics, and more than 30,000 people died in that war between 1991 and 1994.[4] The war ended with Armenia declaring victory, and in 1994, the Artsakh Republic, along with some Azeri lands and villages, was absorbed into Armenia. A ceasefire agreement was signed between Armenia and Azerbaijan that was brokered by Russia, an ally of Armenia back then. Armenia took control of the Nagorno-Karabakh region as per that ceasefire agreement. Russia played a mediator role alongside France and the United States. They tried to find a final agreement and a permanent solution to this conflict, but both Armenia and Azerbaijan refused to agree on terms that would end the war. Instead, Armenia, as the victor, renamed the Azeri-named villages in their newly acquired territory and repopulated those areas with ethnic Armenians. Furthermore, despite the bilateral agreement for a ceasefire between 1994 and September 2020, there have been sporadic clashes between the Armenian and Azerbaijani troops using shelling, attack drones, and special operation activities. In April 2016, there erupted the fiercest fighting ever witnessed since 1994, resulting in hundreds of deaths in the territories.[5] The opposing sides decided to end hostilities four days after the fighting, but a communication breakdown led both parties to begin accusing each other of violating the ceasefire. The tension was still very high this time. The year 2020 saw the outbreak of the second Nagorno-Karabakh war, which began as border skirmishes and bombings turned into a full-scale conflict. A ceasefire was eventually brokered by Russia, which put an end to the bloodshed but did not resolve the ongoing conflict. In 2023, Azerbaijan took complete control of the region after launching a swift offensive they referred to as anti-terrorist operations. The region was formally dissolved into Azerbaijan, while 100,000 ethnic Armenians living in the region were in a dilemma and fled to Armenia.[6]

Water security interests of Azerbaijan and Armenia

Many scientists have predicted an alarming rate of decline in water supplies in Armenia and Azerbaijan. Rainfall water is predicted to drop by a staggering 52 percent by the year 2040, while the decrease in water supply in Azerbaijan is expected to be the reason for a predicted 77 percent decrease in crop yields during the same period.[7] This projected decline is the worst in the Central Asia Region. Severe effects of climate change have been and will continue to be felt, mostly in the downstream Kura-Aras basin, which has the highest agricultural demand and the lowest level of water stream.

(Source: Nareg Kuyumjian/Eurasiane,2021)

How does that relate to the area of conflict? Why is Nagorno-Karabakh important? The Nagorno-Karabakh region is of great significance to both Armenia and Azerbaijan because it holds the tributaries of the Aras, Kura, and Tatar rivers. On the Tatar River specifically, there is the Sarsang Hydro Water Plant and Sarsang Reservoir, which were used to provide irrigation and drinking water to the territory of Nagorny Karabakh and six other close regions of Azerbaijan. But after the 1994 ceasefire agreement, Azerbaijan could no longer use the Sarsang Reservoir.

In 2013, Nagorno-Karabakh’s Prime Minister approached Azerbaijan, offering to share the reservoir, but Baku turned it down.[8] As far as Baku is concerned, it viewed the area as a separatist regime and will not negotiate with an occupying force. On the other hand, for Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh represented a big source of energy due to its large number of hydroelectric plants, and the number of those plants was expected to rise. The region was one of three places Armenia used to import electric energy from, along with Georgia and Iran. Armenia was importing 150 to 200 million kWh from Nagorno-Karabakh.[9] The government of Armenia had also planned to import a much higher amount of electricity from the region in 2021 — 330 million kWh — but imports from Nagorno-Karabakh had to be replaced with much more expensive energy produced locally due to the impending conflict.[10]

The military buildup was evident between 2008 and 2019.[11] Azerbaijan was planning a resurgence. They never let go of what is considered by Azeris to be an occupied region of great significance for hydroelectric plants and water. They allocated $24 billion to the budget for their armed forces.[12] That was six times more than Armenia. They reiterated their claim to Nagorno-Karabakh while doing so. In 2016, following a four-day war between the two countries, it became clear that what many experts were referring to as a “frozen conflict” was actually a simmering conflict.[13]

The Karabakh war was reignited in 2020, after more than two and a half decades since the conflict was frozen. The turning of Azerbaijan into a gas- and oil-rich authoritarian state and the blame for its forfeiture of Karabakh became the motivating factors. During this time, Baku was convinced that it was the right time from a geopolitical standpoint and spent $2.24 billion in military spending in 2020, a 20% increase over the previous years.[14] By 27 September, Azerbaijan was prepared. It launched a surprise offensive and successfully recaptured the lowlands. It launched a second attack in 2023 and took Stepanakert.[15] Almost every ethnic Armenian fled during this time, the same way the Azeris did three decades earlier.

Who is involved in the conflict?

The long-simmering conflict was sparked when another country intervened. Turkey has been getting more involved in regional conflicts to influence the outcomes in their favor. Thus, Turkey seized the chance presented by the resurgence of hostilities in Nagorno-Karabakh in 2020 and sent troops in support of Azerbaijan. It is estimated that the arms trade in 2020 alone has reached over 100 million dollars.[16] These defense and weapon deals included advanced drones, which were vital in the war. In just a week, Azerbaijan pushed in 20 kilometers in Armenian-held territories and pushed later on further to areas in Nagorno-Karabakh. Armenia continued to suffer defeats due to the advanced drones and the amount of military investment made by Azerbaijan. It is speculated that this attack in September 2020 had been planned for months both in Baku and Ankara.[17] On 8 November the same year, Azerbaijan won its first victory by capturing the historical city of Shusha, located only 15 kilometers away from the capital of the autonomously occupied region of Stepanakert.[18] This forced Armenia to surrender and agree to a ceasefire agreement. This agreement significantly altered who would rule over Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijan will retain control over the seized territories plus other parts of Armenia as well, while the ethnic Armenians will continue to govern the central region, which includes the capital Stepanakert. To protect them, they will have two thousand Russian peacekeeping soldiers and the same number of Turkish peacekeeping soldiers as part of the ceasefire agreement. Russia did not intervene in the war, but it was the one that brokered this deal as well and gained what it wanted, which was to expand its circle of influence in the region by having troops on foot and on the ground. As Azerbaijan rejoiced over its victory and the reclaimed territories, Turkey and Russia were accomplishing strategic goals, while Armenia was in disarray after the devastating loss.

The current situation

Following the establishment of a permanent military checkpoint on Lachin in April 2023 by Azerbaijan, all incoming and outgoing traffic was cut off from Stepanakert in the heart of the previously autonomous region, including the electricity and gas cables in the city. For months, Artsakh largely depended on the Sarsang dam for power generation, and this blockage caused the reservoir feeding springs to the Tatar River to drop to significantly low levels. These drops in water levels to 20 meters below have left the ground behind bare, infertile, and sticky. Ilham Aliyev, the Azerbaijani President, has also promised that the newly constructed hydroelectric dams in the area will have a capacity to generate about 270 megawatts by the close of 2024, in addition to the 240 megawatts expected to be generated from solar farms, whose construction will soon commence. Currently, new houses are being fitted with solar panels, climate-monitoring stations and dams undergoing renovation. Replantation projects are also underway to reforest the area and attract native species, including the Eurasian gazelles, following decades of anthropogenic extinction. Climate concerns and the environment are now a focus, with a net-zero carbon emission commitment by 2050.

The current situation in 2024 is promising for correcting the state of affairs that has left Nagorno-Karabakh a conflict zone since the 1990s. While it is time to rebuild and recover from a territorial dispute that has had an enormous impact on water scarcity in the region, war has stripped the region of its color and life. The remains of Azeri and Armenian villages, which were once boasting fertile soils, are now filled with shells, tanks, and bullets. In much of the land, only a few things have survived the destruction, such as the pomegranate trees whose fruits are never harvested, which the region is famous for. Officially, in January 2024 the Republic of Artsakh ceased to exist and Nagorno-Karabakh became under the full control of Azerbaijan.[19] Today, the area has remained closed to public access and foreign media. Nevertheless, there are several projects, underway to rebuild the villages and demine sites, airports, and roads, as well as reforestation to accommodate those who have fled due to conflict.

The peace talks that have been going on in Germany since February 2024 are showing a lot of promise and building a great deal of hope will be necessary to find a permanent solution to the lingering conflict. Both Armenian Prime Minister Niko Pashynian and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev have stated that they are ready to solve the outstanding issues between the two countries through peaceful means.[20] However, Azerbaijan also accuses the EU of pliantly ignoring the facts and demonizing Azerbaijan while taking sides with Armenia. At the same time, Azerbaijan’s President reassured the EU that Baku has no intention of attacking Armenia and only wants what is rightfully theirs, according to Azerbaijan. Armenia, on the other hand, has lost faith in Russia, which is currently preoccupied with its war with Ukraine, and has found itself embraced by the EU as a new ally. As of March 2024, there were talks and speculations about Armenia’s potential for EU membership.[21]

Even though the fighting is over and the Republic of Artsakh is torn between official dissolution and going back on it, there is still a conflict going on: repairing the damage caused by the war and restoring the natural environment. In the conflict in Karabakh, nature has been a victim and an important source of support. The landscape has always been a source of conflict because it serves as a center of misinformation. For instance, in September 2020, forest fires broke out in the territories, but the Azerbaijani and Armenian armies blamed each other for causing the fires. Environmental disputes have been the mainstay of the region. Earlier in January 2023, Azerbaijan threatened to sue the Armenians with the Council of Europe for violating the Bern Convention.[22] Under the European Natural Habitats and Wildlife Conservation, conservation efforts are overseen by the Bern Convention.

Azerbaijan has massive water plans for the territory it gained back. It was announced that at least five hydroelectric power plants will be commissioned in Lachin District 2024. These plants will generate at least 40 megawatts of electricity for Azerbaijan. To put things in perspective, the Lachin district, which Azerbaijan was able to retake, currently produces 77 million kWh of green energy from hydroelectric plants, which is the equivalent of 18 million cubic meters of gas.[23] This only serves to emphasize that, although not the driving force of the conflict, water interest was undoubtedly a contributing factor.

Conclusion

Although one of the main Sustainable Development Goals set forth by the United Nations to be achieved by 2030 is access to clean water and sanitation, some regions find it difficult to meet this goal due to conflicts over natural resources around the world. The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict in Central Asia is one such conflict that has afflicted the region for decades. However, there are notable developments that will restore the region’s glory, but UNEP reports have warned about the current activities of constructing new towns and villages. For instance, waste from demolition sites is being dumped into landfills, and the construction of new roads is further destroying forests in the region. Nevertheless, Azerbaijan’s Deputy Minister for Ecology, Umayra Taghiyeva is optimistic as the region looks forward to making a great green return while focusing on the future.[24] On the other hand, Baku is committed to pushing its green public relations campaign towards the end of 2024 during COP29. This campaign was won with support from Armenians. However, the likelihood of this initiative succeeding is low since Azerbaijan is known for petrochemical production. Critics have called such a move mere lip service in its commitment to sustainability. In general, efforts to restore the region will take a long time. For instance, demining alone will take several years, with reconstruction and rehabilitation of the landscape expected to take even longer. Positive signs that the decades-long conflict has been managed, can be seen in President Aliyev’s increased fame following his victory in Karabakh and later its reconstruction. Residents are trolling back, and the fierce war critics and most political opponents are now in exile, which doesn’t look well for Azerbaijan on the transparency scales and global politics, but it might have temporary stabilizing effects domestically. In the end, local support and government efforts to resolve disputes will eventually restore peace in the region.

[1] World Economic Forum, “The World Economic Forum,” n.d. https://www.weforum.org/.

[2] “Nagorno-Karabakh conflict,” Center for Preventive Action, March 20, 2024, accessed 19th March, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/nagorno-karabakh-conflict.

[3] Ani, Avetisyan, A. & Sevada, Ghazaryan, “The loss of Artsakh’s HPPs and the severe financial blow to Armenia,” Union of Informed Citizens, November 11, 2021, Accessed March 20, 2024, https://uic.am/en/14578.

[4] “Explainer: What Is Happening between Armenia and Azerbaijan Over Nagorno-Karabakh,” Reuters, September 20, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/what-is-happening-between-armenia-azerbaijan-over-nagorno-karabakh-2023-09-19/.

[5] Council on Foreign Relations, n.d. https://www.cfr.org/.

[6] “Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict,” Center for Preventive Action, op. cit.

[7] Nareg Kuyumjian, “Perspectives: Don’t Water It down: The Role of Water Security in the Armenia-Azerbaijan War,” Eurasianet, December 22, 2021, https://eurasianet.org/perspectives-dont-water-it-down-the-role-of-water-security-in-the-armenia-azerbaijan-war.

[8] Hannah, Smith L, “The land that was one Nagorno-Karabakh.”, Pulitzer Center, February 28, 2024, Accessed March 19, 2024, https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/land-was-once-nagorno-karabakh.

[9] Ani Avetisyan, “Weaponizing Energy: Nagorno-Karabakh’s Energy Supplies under Siege,” EVN Report, February 9, 2023, https://evnreport.com/spotlight-karabakh/weaponizing-energy-nagorno-karabakhs-energy-supplies-under-siege/.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Sam Bhutia, “Armenia-Azerbaijan: Who’s The Big Defense Spender?,” Eurasianet, October 28, 2019, https://eurasianet.org/armenia-azerbaijan-whos-the-big-defense-spender.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “Military Expenditure (Current USD) – Azerbaijan,” World Bank Open Data, accessed March 2024, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.CD?locations=AZ.

[15] Smith, Hannah Lucinda, “Environmental Concerns Loom Over Azerbaijan’s Reconstruction of Nagorno-Karabakh,” Foreign Policy, March 1, 2024. https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/02/27/nagorno-karabakh-azerbaijan-armenia-environment-climate/.

[16] Ece, Toksabay, “Turkish sale to Azerbaijan surged before Nagorno-Karabakh fighting.” Reuters, October 14, 2020, Accessed March 19, 2024,fhttps://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN26Z237/.

[17] Seth Frantzman, “How Turkey Pushed for Azerbaijan’s War on Armenia – Analysis,” The Jerusalem Post, October 14, 2020, https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/how-turkey-pushed-for-azerbaijans-war-on-armenia-645650.

[18] “Azerbaijan Says It Seized Nagorno-Karabakh’s 2nd-Largest City,” Al Jazeera, November 8, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/11/8/azerbaijan-says-it-seized-nakarno-karabakhs-2nd-largest-city.

[19] Smith, “Environmental Concerns Loom Over Azerbaijan’s Reconstruction of Nagorno-Karabakh,” op. cit.

[20] Sarah Marsh, “Germany Hosts Peace Talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan,” Reuters, February 28, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/germany-hosts-peace-talks-between-armenia-azerbaijan-2024-02-28/.

[21] “Armenia Is Considering Seeking EU Membership, Foreign Minister Says,” Reuters, March 9, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/armenia-is-considering-seeking-eu-membership-foreign-minister-says-2024-03-09/.

[22] Smith, “Environmental Concerns Loom Over Azerbaijan’s Reconstruction of Nagorno-Karabakh,” op. cit.

[23] Farid Zohrabov, “Azerbaijan Airs Commissioning of New Hydropower Plants in Its Lachin This Year (Video),” Trend.Az, February 15, 2024, https://en.trend.az/business/green-economy/3862557.html.

[24] Smith, “Environmental Concerns Loom Over Azerbaijan’s Reconstruction of Nagorno-Karabakh,” op. cit.