When looking at post-colonial societies, one may observe the enduring challenges that these societies face due to the legacy of colonial rule. Take Sri Lanka as an example; beneath the calm beauty of the country’s palm-fringed shores lies a history marked by division, mistrust, and decades of bloodshed.

After gaining its independence from British rule in 1948, Sri Lanka found itself engulfed in a civil war, grappling with profound ethnic tensions between its two national groups: the Sinhalese, who formed the majority, seeking to assert political dominance and the Tamils, who constituted a significant minority, striving for equal representation and an independent state.[1] Despite four attempts at peace, tensions between these two ethnic groups persisted for nearly three decades, leaving tens of thousands dead and hundreds of thousands displaced.[2]

The principal actor throughout this conflict representing the Tamils was the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), an ethnic separatist movement founded by Vellupillai Prabhakaran in the early 1970s, demanding a sovereign state known as Tamil Eelam. The LTTE emerged as a direct reaction to the decades of systematic state repression that ultimately thwarted democratic efforts and deprived the Tamil minority of linguistic, educational and employment rights.[3] Over the years, the group was able to evolve from a small localized insurgency into a highly organized, militarily sophisticated and transnational non-state actor. Its transformation demonstrates how identity-based movements can radicalize when peaceful political avenues are blocked and how separatist ambitions can evolve into protracted armed conflict.

Hence, this insight aims to answer the following research question:

How did the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) transform from a primarily separatist movement (whose main intention was to secure a homeland for the Tamils in Sri Lanka) into one of the most advanced and sophisticated insurgent and terrorist organizations of the 20th century, and what does this development tell us about the characteristics of contemporary ethno-political violence?

The Rise of the LTTE and Its Initial Strategy

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) rose to the scene in the mid-1970s as a result of the long-standing historical injustices that were rooted in British colonial favoritism and sustained by post-independence policies that reinforced ethnic hierarchies. During the British colonial era, Tamils were disproportionately advantaged in sectors like education and civil service, establishing structural privileges that fostered resentment among the Sinhalese population.[4]

However, after gaining independence from British rule in 1948, these privileges soon reversed as power distribution shifted in favor of the Sinhalese. Driven by the desire to rectify previous discriminations, reclaim political dominance and consolidate state power, the Sinhalese started enacting laws and policies discriminatory toward the Tamil minority. Thus, what began as a hope for harmonious coexistence between the two ethnic groups quickly deteriorated. The Tamils, living mostly in the northern part of the country, started feeling increasingly marginalized by the Sinhalese majority as they sought to impose and institutionalize Sinhala-Buddhist supremacy in the makeup of the Sri Lankan state.[5] Fears among the Tamils were further heightened when the Sinhalese reinforced the 1972 Republican Constitution, also known as “the Sinhala Only Act”, which enshrined discrimination into law.[6] It declared Sinhala the sole national language, centralized political power in Sinhalese majority areas, and symbolically excluded Tamils from participating in the nation’s educational, political and cultural life.[7] The government also forced the Tamils to swear an oath of allegiance, denouncing their Tamil identity. It was thus, within this atmosphere of exclusion and resentment, that Vellupillai Prabhakaran took up his radical path and formed the group in 1976. He was determined to channel the Tamils’ grievances into an organized armed resistance, carrying the belief that violence is the Tamils’ only resort after all.

The Black July riots, which took place on the 23rd of July 1983, marked the critical turning point that propelled the LTTE to dominance and sparked the beginning of Sri Lanka’s civil war. On that day, members of the LTTE ambushed a military patrol near Jaffna, killing around 13 Sri Lankan soldiers. The government’s response was brutal. It unleashed a state-sanctioned anti-Tamil program carried out by Sinhala civilians, devastating the Tamil population and legitimizing the appeal of armed insurgency. In mobs, the Sinhalese roamed the streets attacking Tamils and their properties, armed in some cases with voter lists to help them identify Tamil targets.[8] The chaos extended beyond the northern regions into Colombo and the hill country, where thousands lost their lives, and the Tamil economy faced devastating setbacks. It even spread to the Welikada prison, where Sinhala prisoners murdered 53 Tamil detainees over two days while guards allegedly looked on. This collective trauma reinforced the dominant perception within the Tamil community that violence is the sole path to self-determination. It triggered a massive wave of voluntary recruitment into the LTTE and other Tamil militant groups.[9] [10]

By the end of July, Sri Lanka found itself engulfed in a civil war with the LTTE being the central non-state actor, transforming the ethnic dispute into a protracted armed conflict. To take revenge, the group pursued an advanced military strategy that combined guerrilla warfare, territorial control and high-profile suicide attacks. In the early stage, the group carried out attacks against military convoys, police stations and government installations in the North and the East. By the late 1980s and the 1990s, the LTTE had established control over substantial areas and pioneered large-scale suicide bombings through its Black Tigers Unit. For instance, in 1991, the group assassinated the Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in retaliation for sending Indian troops to combat them. Other attacks also included the assassination of the Sri Lankan President Ranasinghe Premadasa in 1993. Not only that, but the group also attacked economic infrastructure like the Central Bank in 1996 and Colombo International Airport in 2001. During each phase of its fighting, the group also engaged in conventional campaigns, attempting to hold territory through direct confrontations with government forces.

Despite engaging in multiple rounds of peace negotiations between 1985 and 2002 with the Sri Lankan government, where India and Norway were the brokers, tensions remained, dragging both parties back to war. The LTTE consistently regarded the ceasefires as strategic pauses rather than genuine measures toward peace. It capitalized on the breathing room to reorganize, resupply and reaffirm its forces. When negotiations were stalled or when political conditions changed, the group resumed its military attacks.[11] The year 2006 saw the conflict resume on a large, brutal scale. The third phase of the civil war, which was known as Eelam War IV, although concluded in 2009, witnessed the LTTE executing progressively desperate operations in response to the advancing government forces. The group persisted with suicide attacks and attempted major military offensives; however, it ultimately lacked the necessary resources and external support to continue the conflict.[12]

Goals and Ideology

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam’s belief system was built around one primary goal: to attain an independent Tamil homeland, “Tamil Eelam”, in the northern and eastern parts of Sri Lanka, where most of the Tamils reside. After decades of failed political engagement and after the 1983 Black July violence, the Tamils saw this outcome as the only path forward.[13] In their ideology, they focused less on explaining why the Tamils wanted independence and more on how they wanted their new state to work. Forming their ideology from the start was the Marxist and socialist thought. The group wanted to create a society where class and class divisions disappeared, where wealth was shared more fairly, and where a single political party, led solely by Vellupillai Prabhakaran, would guide the nation. This ideology helped the group attract recruits from many different backgrounds, ranging from rural farmers to educated youth. Even women were encouraged and mobilized to serve as fighters and protectors of the Tamil community.[14] [15]

The unwavering loyalty to Prabhakaran as a leader was one of the most striking features of the group’s ideology. Within the group, Prabhakaran was elevated to almost mythic status, often called the Surya Thevan, meaning sun deity, by the Tamil fighters and his supporters.[16] New recruiters were also forced to swear an unconditional oath of loyalty to him and pledge absolute allegiance to the Tamil Eelam cause, demonstrating their commitment through symbolic acts such as carrying cyanide capsules to be consumed if captured. This focus on self-sacrifice turned martyrdom into a badge of honor and reinforced a strict, disciplined lifestyle where even smoking, drinking and any form of dissent were prohibited. It was this culture of absolute obedience and willingness to sacrifice that enabled the LTTE to maintain operational cohesion despite external pressures.[17]

The LTTE Oath

“For the supreme cause of our revolutionary movement, which is the liberation of Tamil Eelam, egalitarian and sovereign, I swear the oath that I will fight with all my soul, my life, my body, and my goods, and I will freely accept the command of our leader, the honorable Vellupillai Prabhakara. The thirst of the Tigers is the motherland of Tamil Eelam [repeated three times].”

(Fuglerud, 2024).

Although the LTTE later eliminated rival Tamil groups (a point we will explore in the following section), it initially presented itself as the sole representative of Tamil self-determination. Prabhakaran argued that negotiations and peaceful protest would never succeed. The mantra “hit and grab” summed up the belief that only sustained armed effort could bring about Tamil Eelam.[18] As the movement grew, its ideological commitments shaped its internal structure. As we will see in the next section, the group evolved from a small guerrilla outfit into a highly coordinated force with a specialized military force. This evolution was portrayed as a living embodiment of the socialist vision the LTTE claimed to uphold: a disciplined, self-sufficient community ready to become the foundation of an independent Tamil Eelam.[19]

Instruments and Tactics

The LTTE functioned as one of the most sophisticated and ruthless militarized terrorist organizations of its time. Upon its formation, it competed with approximately 37 Tamil militant groups, some of which included the Tamil Eelam Liberation Organization (TELO), the Eelam Revolutionary Organization of Students (EROS), the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF), and the People’s Liberation Organization of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE).[20] Despite initial setbacks such as being outgunned and outnumbered by its rivals, the LTTE rapidly “established itself as indisputably the predominant Tamil separatist organization” and the sole representative of the Tamil struggle within a span of six months in 1986. This swift ascension was primarily driven by the group’s rigorous discipline, effective tactical coordination, and adoption of advanced innovative military strategies.[21]

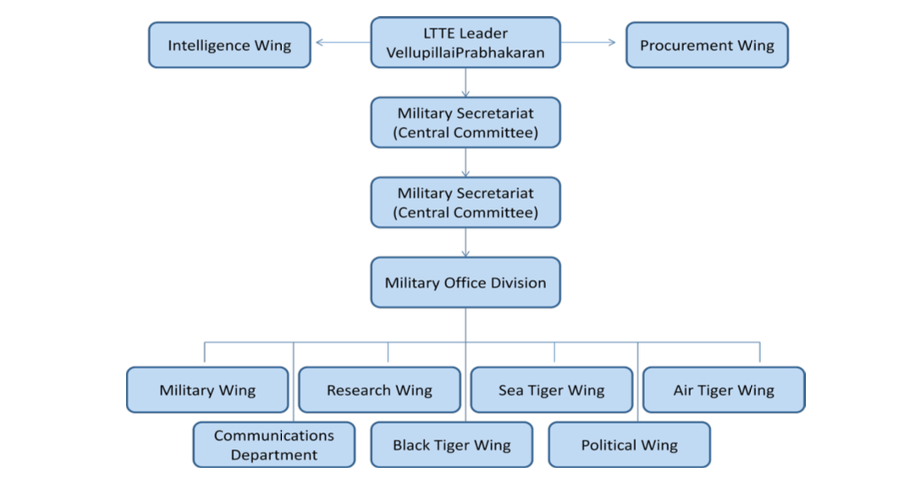

Under the absolute and central command of Prabhakaran, the LTTE developed a highly disciplined and structured hierarchy. As shown in the figure below, the group comprised various wings, each with specific roles and responsibilities that contributed to the group’s overall effectiveness. The military wing, for instance, was responsible for combat operations on land while the sea tiger wing managed maritime activities, including naval attacks and sabotage missions at sea.[22]

Figure 1: Outline of the LTTE organizational structure

Source: Silva, 2013.

The air tigers represented the most unique component of the group. The LTTE was the only terrorist organization equipped with its own air wing, the so-called Air Tigers, and despite rumors in the 1990s about its existence, it was not until the early 2000s that these claims were confirmed through actual air operations during the later phases of the conflict. The group’s political wing managed diplomatic initiatives, negotiations and propaganda, whereas the intelligence and research wing collected essential information and executed espionage activities. As mentioned previously, the Black Tigers, known for their suicide attacks, also added a lethal edge to the LTTE tactics. They were made up of only the most devoted and dedicated tigers.[23] The group has also incorporated civil administration units, which oversaw governance and social services.

Militarily, the group established a formidable military identity that transformed insurgency tactics in contemporary contexts. By seamlessly integrating guerrilla warfare with conventional military strategies, the LTTE crafted a distinctive and highly effective insurgent model that struck fear across the region. In their early stages, they relied heavily on covert ambushes, sabotage operations, and hit-and-run tactics to undermine enemy forces and establish dominance over key territories.[24] This tactical sophistication was significantly enhanced through external support, particularly from India’s Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), which provided rigorous training in advanced warfare techniques following the devastating 1983 Black July riots. This external support empowered the LTTE to enhance its operational capabilities significantly.[25] As mentioned earlier, the organization’s most groundbreaking innovation was the implementation of mass casualty suicide bombings, executed by their elite Black Tigers unit. This tactic, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, not only redefined asymmetric warfare but also set a new benchmark for terrorist activities worldwide.[26]

During the late 1980s through the early 2000s, the LTTE also skillfully capitalized on the vacuum left by the Indian Peacekeeping Force (IPKF) and the Sri Lankan government to establish a de facto state and administration in the unoccupied northern and eastern regions of the island, particularly Jaffna and parts of Wanni.[27] [28] By presenting itself as the guardian of the Tamil community, the group gradually built a complex web of institutions within these territories that mimicked those of a sovereign state. It set up courts to uphold a form of justice, formed police units to maintain order, and established administrative offices that issued travel passes. Recognizing the importance of social stability, the LTTE also provided essential services such as schools and healthcare facilities, which helped garner support and loyalty among the local population for the short term until fears deepened and the group’s authoritarian control became more pronounced.[29] [30]

In addition, the LTTE’s ability to sustain its operations was underpinned by a sophisticated and multifaceted economic system. Within the territories it occupied, the LTTE imposed a rigorous and methodical taxation system, collecting about 12% from government employees and imposing customs duties of 10% to 30% on imported goods, which brought in roughly $30,000 to $40,000 of revenue each month.[31] To sustain its operations and control in the region, the group also relied heavily on developing the Tamil diaspora; an extensive funding network spanning across India and various Western countries, particularly Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom, generating around $200 to $300 million annually. According to reports, networks operating within Canada alone have provided the group with roughly $12 million per year.[32] The LTTE also secured a significant amount of its funding by engaging in criminal activities. It controlled most human smuggling operations, earning $18,000 to $32,000 per trip, trafficking heroin since the 1980s across countries like Canada, France, Italy, Poland, and Switzerland, and operating a fleet of merchant ships registered in Panama, Honduras, and Liberia that mostly carried legitimate cargo but also secretly transported weapons and explosives.[33]

The Defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

Following the August 2005 assassination of Sri Lankan foreign minister Lakshman Kadirgamar, the LTTE fueled the government’s growing determination to finish off the Tigers once and for all. When the former President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government came into power in 2005, he promised to wipe out the LTTE. Unlike previous governments that sought negotiated settlements, Rajapaksa’s vow was firm: destroy the group no matter the cost.[34] [35]

However, to turn the promise into reality, the government needed money, weapons and the freedom to use them without constant Western criticism. Two developments made this possible. First, China began pouring about 1 billion US dollars a year into Sri Lanka’s defense budget from 2005 onward, supplying modern artillery, aircraft, naval vessels and training. Because the funds came from China, Sri Lanka was no longer forced to obey the human rights conditions that Western donors often attached to aid.[36] Second, Rajapaksa appointed his brother Gotabaya, who was a retired army officer, as the government’s Secretary of Defense. Gotabaya reshuffled the top brass, installed aggressive, battle-tested commanders, upgraded the military equipment and launched a massive recruitment drive that increased the army’s size by roughly 70% and the defense budget by 40% within three years.[37] [38]

With the political will, the money and the leadership in place, the army launched what became known as Eelam War IV. However, the conflict did not start with a spectacular battle; it began in July 2006 when the LTTE blocked the sluice gates of the Mavil Aru dam, cutting water to thousands of families in government-held areas. Instead of conducting talks, Rajapaksa ordered an immediate all-out military response.[39] [40] The navy, now equipped with modern patrol boats and helicopters, systematically destroyed the LTTE’s Sea Tigers and their maritime smuggling network. Over ten floating warehouses that sorted weapons and ammunition were blown up, cutting off the group’s supply line.[41]

On land, the army pushed forward relentlessly. By mid-2007, the entire Eastern Province was cleared of the LTTE fighters, depriving the rebels of a major recruiting base and a source of revenue. In January, the army captured Kilinochchi, the LTTE’s de facto capital, and continued to advance into the heart of the north. On the 19th of May 2009, after weeks of fierce fighting, the Sri Lankan army cornered the LTTE leader Prabhakaran near the Nandikadal lagoon and killed him, ending the 26-year-long civil war in Sri Lanka.[42] [43]

Yet the LTTE’s defeat was not solely due to Sri Lanka’s military strength and China’s support. According to various reports, several factors had already contributed to the weakness of the group prior to the rise of Sri Lanka’s new president, Mahinda Rajapaksa. These included internal divisions, loss of legitimacy, and international support and funding.

The group’s most damaging internal blow came in March 2004, when the LTTE’s eastern province commander, Vinayagamoorthi Muralitharan, also known as Colonel Karuna Amman, defected from the group with his 6,000 followers and reconciled with the Sri Lankan government after a disagreement with Vellupillai Prabhakaran and losing faith in his leadership.[44] This split shattered the group’s unity, weakened its manpower, and exposed growing dissent within its ranks. In exchange for amnesty, Karuna provided the Sri Lankan army with assistance and advice on the group’s bases, operations, tactics, and how to defeat them, which eventually weakened the LTTE’s grip in the eastern portion of the country and helped the military achieve subsequent success.[45] By forming his own faction of a political party, Tamil Makkal Viduthalai Pulikal (TMVP), with the support of the Sri Lankan government, Karuna weakened the group further. He reduced the LTTE’s support in several areas, providing the war-weary population an alternative to Prabhakaran’s iron-fisted rule and a potential future voice in Sri Lankan politics.[46]

As has been evident, Prabhakaran’s increasingly brutal autocratic rule caused the group to unravel from within. What began as a legitimate liberation movement in the eyes of the Tamils transformed into a rigid, cult-like organization centered entirely around Prabhakaran, and those who questioned him were either silenced or killed.[47] Although this centralized control and atmosphere of fear were successful at first, they rendered the group ill-equipped to handle strategic challenges in the mid-2000s. Prabhakaran’s brutal treatment of Tamil civilians had also eroded public support among the Tamil population. The LTTE’s own people grew tired of killings, violence, forced recruitment, child soldier abduction and the harsh rule that Prabhakaran resorted to in order to replenish manpower after lacking the number of voluntary cohorts it enjoyed in its early years. This continuous cycle of atrocities, using civilians as human shields against the government and executing Tamils attempting to flee, turned the local population against the group, shifting its campaign into a de-escalation phase toward the end.[48] [49] Prabhakaran’s subsequent diversion of relief supplies and aid intended for survivors after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami to its own military needs also damaged the group’s credibility and the support it desperately needed. Many saw this as a betrayal; the group that had once been viewed as a protector of the Tamil community now appeared to be a violator of its people’s own rights.[50]

However, none of this internal decay would have mattered as much without a seismic shift in global politics. In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, the LTTE faced a severe downfall that shattered its organizational strength, dismantled its network, and left it struggling to recover even a fraction of its previous stature. Despite a fundamentally changed global environment toward non-state groups after 9/11, the group continued its campaign of violence, relying heavily on suicide bombings, attacks on civilians as a tactic, and supplying global terror groups. In response, the United States added the group to its Foreign Terrorist Organization list and upgraded it to Specially Designated Global Terrorist status in 2001.[51] Canada in 2005 and the European Union in 2006 followed suit, banning the LTTE’s fundraising. The diaspora that had previously sent $100 million or more each year to the group suddenly saw its financial channels frozen. Without that cash flow, the LTTE could no longer purchase weapons, maintain its overseas networks, or sustain its elaborate social-service programs. Had 9/11 not reshaped the international counter-terrorism policy, the group would have retained a crucial source of money.[52]

From his side, Prabhakaran also made poor strategic and tactical choices that cost the group key international backing and doomed its movement long before the government began its final offensive. Its most damaging miscalculation was the assassination of former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1991 by a female Tiger suicide bomber. This poor strategic act turned India, which was once a crucial source of political and logistical support to the group, into a strong opponent. It cost the LTTE much of its sympathy among the Tamils in India’s Tamil Nadu state and led to its official ban in 1991.[53] [54]

By 2009, the LTTE, which had once controlled large parts of the north and east, had become a mere shadow of its former self: bankrupt, isolated, illegitimate, divided and incapable of responding to an invigorated government offensive of any kind.[55] With the Sri Lankan government’s victory, affirmed by the death of Velupillai Prabhakaran, the group was eventually defeated. Yet the group’s defeat did not come without cost. In fact, the civil war claimed an estimated 70,000 to 80,000 lives, with both the LTTE and the Sri Lankan government forces accused of grave human rights violations and war crimes. Although the group’s military structure was dismantled and its leader, Prabhakaran killed, the fundamental political and ethnic grievances fueling the conflict remain unresolved. Tamil communities continue to face pervasive surveillance, discrimination in employment and social matters and restrictions under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA). These ongoing injustices sustain Tamil nationalist sentiment, particularly within the international diaspora, which, according to the Sri Lankan government, maintains efforts to revive the separatist cause and perpetuate the LTTE’s legacy.[56]

Lessons for Contemporary Ethno-Political Violence

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam stands out today as a striking example of how a separatist movement can transform into one of the most advanced and sophisticated militant groups of its time. It also offers leaders, policymakers and peacebuilders several lessons for understanding, addressing and perhaps preventing ethno-political violence from taking place in today’s geopolitical landscape:

- The LTTE case study has come to prove that a military victory, while sometimes necessary, is insufficient on its own to resolve deeply rooted ethnic grievances and political marginalization. As mentioned earlier, the Sri Lankan government’s decisive military victory in 2009 succeeded in dismantling the LTTE’s organizational structure. However, the underlying political and ethnic grievances that fueled the three-decade war remained unsolved, sustaining separatist sentiment within diaspora communities. Hence, the essential lesson here is that achieving lasting peace requires political settlements that address the root causes of the conflict, not just the military suppression of armed groups. Doing that will foster genuine understanding and cooperation among all parties involved.

- The long-standing marginalization of Tamils in Sri Lanka is an example of the systemic ethnic discrimination and political exclusion that often generates profound anger and deepens divisions within a society. For decades, Tamils have faced unequal treatment, restricted opportunities, and marginal political representation, which has deepened feelings of resentment and injustice, fueling grievances that ultimately led to widespread support for the LTTE. Promoting open dialogue between all involved parties is essential for bridging divides. Also, addressing inequalities, promoting inclusive governance, and ensuring equal participation for all communities are crucial steps toward peace. By fostering understanding and fairness, societies can help prevent the cycle of violence and build a more harmonious, resilient future for diverse populations.

- Previous sections have clearly established that the sustainability of militant groups is heavily reliant on external funding and the backing of diaspora support networks. The LTTE, for instance, managed to survive for nearly three decades largely because Tamil communities abroad channeled millions of dollars into the group. It provided them with the necessary resources for recruitment, funding weapons, and operating activities. Disrupting these funding streams by implementing international sanctions, banking control and taking legal actions proved to be essential in weakening the LTTE’s capabilities and hindering its capacity to carry out attacks. Applying the same mechanisms against current militant groups that rely on similar foreign funding support could prove to be effective.

- Perceived organizational legitimacy within target populations shapes insurgency success. The LTTE cultivated an image of the defenders of Tamil rights, portraying themselves as the only group willing to protect their people against state oppression. This narrative helped them recruit, retain popular support, and justify extreme tactics such as suicide bombings. Counterinsurgents must therefore do more than fight; they must actively demonstrate a commitment to redress grievances, protect minorities, and establish an inclusive political process that removes the insurgents’ rationale for existing.

- Post-conflict reconciliation requires addressing not only military defeat but also enduring structural inequalities. Tamil communities’ continued marginalization through surveillance, legal restrictions and discrimination perpetuates grievances that sustain separatist ideology. Comprehensive peacebuilding frameworks must combine truth commissions, transitional justice mechanisms, and substantive political reforms that dismantle the discriminatory structures originally fueling conflict. Without such multidimensional approaches, military victories risk creating cycles of renewed violence rather than durable peace.

With all of that being said, the LTTE experience vividly illustrates that achieving lasting peace is a complex process that demands a comprehensive and multifaceted approach. Violence stemming from ethnic and political marginalization cannot be defeated by force alone. Genuine peace, reconciliation and stability come from five core themes: addressing inequality, dismantling insurgent financial systems that fuel conflicts and insecurity, offering legitimate political channels, offering equitable opportunities and ensuring justice for all communities. Only through a multipronged approach like such can societies move beyond the cycle of violence and toward sustainable peace.

Conclusion

To conclude, the rise of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam was never an overnight phenomenon. Several historical records traced back the group’s rise to Sri Lanka’s post-colonial era, highlighting the ethnic tensions that prevailed between the Sinhalese and Tamil populations. As has been evident, the government policies that favored Sinhalese speakers created a persistent pattern of institutional discrimination against the Tamil minority. The LTTE, hence, did not emerge as a criminal enterprise but rather as a response to grievances that the 1948 Sri Lankan political system failed to address. The current situation of the group serves as a case study of how extended marginalization, grievances tied to identity and governmental oppression can evolve nationalist movements into forms of militarized extremism. In other words, it underscores the complexity of modern ethno-political conflicts, where insurgent groups blend political, military and social structures to challenge state power. For governments, policymakers and peacebuilders, the LTTE’s story must serve as a cautionary example, if it hasn’t already, to prevent similar movements from emerging in the future.

[1] Rashmi Raghav, “Why and How the Tamil Tiger Lost the Battle: LTTE Case Study,” International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research 4, no. 3 (2016): 53–60, https://www.researchpublish.com/upload/book/Why%20and%20how%20the%20Tamil%20Tiger-3462.pdf.

[2] Kara Joyce, “Gender Roles and Military Necessity: Women’s Inclusion in the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” Georgetown Security Studies Review 11, no. 1 (August 2023), https://repository.digital.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/1086551.

[3] Sara De Silva, “Change and Continuity in Terrorism: An Examination of the Lifecycle of the Liberation of Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” Publicationslist.org. Thesis, 2013, https://ro.uow.edu.au/articles/thesis/An_examination_of_the_lifecycle_of_The_Liberation_of_Tigers_of_Tamil_Eelam/27663021?file=50373045.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Kate Cronin-Furman and Mario Arulthas, “How the Tigers Got Their Stripes: A Case Study of the LTTE’s Rise to Power,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 47, no. 9 (December 27, 2021): 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610x.2021.2013753.

[6] Walter Schwarz, “The Tamils of Sri Lanka,” Minority Rights Group , 1979, https://minorityrights.org/resources/the-tamils-of-sri-lanka.

[7] Sara De Silva, “Change and Continuity in Terrorism: An Examination of the Lifecycle of the Liberation of Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” Publicationslist.org. Thesis, 2013, https://ro.uow.edu.au/articles/thesis/An_examination_of_the_lifecycle_of_The_Liberation_of_Tigers_of_Tamil_Eelam/27663021?file=50373045.

[8] Kate Cronin-Furman and Mario Arulthas. “How the Tigers Got Their Stripes: A Case Study of the LTTE’s Rise to Power,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 47, no. 9 (December 27, 2021): 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610x.2021.2013753.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Rashmi Raghav, “Why and How the Tamil Tiger Lost the Battle: LTTE Case Study,” International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research 4, no. 3 (2016): 53–60, https://www.researchpublish.com/upload/book/Why%20and%20how%20the%20Tamil%20Tiger-3462.pdf.

[11] Mapping Militants Project, “Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam,” 2015, https://doi.org/10.25613/g0k4-wf70.

[12] Sara De Silva, “Change and Continuity in Terrorism: An Examination of the Lifecycle of the Liberation of Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” Publicationslist.org. Thesis, 2013, https://ro.uow.edu.au/articles/thesis/An_examination_of_the_lifecycle_of_The_Liberation_of_Tigers_of_Tamil_Eelam/27663021?file=50373045.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Kara Joyce, “Gender Roles and Military Necessity: Women’s Inclusion in the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” Georgetown Security Studies Review 11, no. 1 (August 2023), https://repository.digital.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/1086551.

[16] Øivind Fuglerud, “Martyrs, Traitors, and the Eelam-Tamil Nation,” The Brown Journal of World Affairs 31, no. 1 (2024): 162, https://bjwa.brown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/WEBSITEFUGLREUD.pdf.

[17] Joanne Richards, “An Institutional History of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE),” Graduate Institute Geneva Institutional Repository 2014, https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-r9gn-n764.

[18] Muttukrishna Sarvananthan, “‘Terrorism’ or ‘Liberation’? Towards a Distinction: A Case Study of the Armed Struggle of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE),” Perspectives on Terrorism 12, no. 2 (April 30, 2018), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3172218.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Sara De Silva, “Change and Continuity in Terrorism: An Examination of the Lifecycle of the Liberation of Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” Publicationslist.org. Thesis, 2013, https://ro.uow.edu.au/articles/thesis/An_examination_of_the_lifecycle_of_The_Liberation_of_Tigers_of_Tamil_Eelam/27663021?file=50373045.

[21] Kate Cronin-Furman and Mario Arulthas, “How the Tigers Got Their Stripes: A Case Study of the LTTE’s Rise to Power,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 47, no. 9 (December 27, 2021): 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610x.2021.2013753.

[22] Sara De Silva, “Change and Continuity in Terrorism: An Examination of the Lifecycle of the Liberation of Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” Publicationslist.org. Thesis, 2013, https://ro.uow.edu.au/articles/thesis/An_examination_of_the_lifecycle_of_The_Liberation_of_Tigers_of_Tamil_Eelam/27663021?file=50373045.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Rashmi Raghav, “Why and How the Tamil Tiger Lost the Battle: LTTE Case Study,” International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research 4, no. 3 (2016): 53–60, https://www.researchpublish.com/upload/book/Why%20and%20how%20the%20Tamil%20Tiger-3462.pdf.

[25] Joanne Richards, “An Institutional History of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE),” Graduate Institute Geneva Institutional Repository, 2014, https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-r9gn-n764.

[26] Niel A. Smith, “Understanding Sri Lanka’s Defeat of the Tamil Tigers by Smith,” Joint Force Quarterly, no. 59 (October 2010): 40–44, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-59/jfq-59_40-44_Smith.pdf?ver=8NrZ-_3wIjxkUc7YJqVKIA%3D%3D.

[27] Joanne Richards, “An Institutional History of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE),” Graduate Institute Geneva Institutional Repository, 2014, https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-r9gn-n764.

[28] Øivind Fuglerud, “Martyrs, Traitors, and the Eelam-Tamil Nation,” The Brown Journal of World Affairs 31, no. 1 (2024): 162, https://bjwa.brown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/WEBSITEFUGLREUD.pdf.

[29] Joanne Richards, “An Institutional History of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE),” Graduate Institute Geneva Institutional Repository (Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies), 2014, https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-r9gn-n764.

[30] Velummylum Manoharan, “Re: Letter of Authorization for the Filing of a Legal Action and Representation of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in the Judicial Review of the Terrorist Designation of the Organization pursuant to Section 219 of the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996. (Public Law 104-132, April 24, 1996),” Their Words, November 6, 1997, http://theirwords.org/media/transfer/doc/lk_ltte_1997_09-a564bb159cd0d6f66aeb0fbc85e51abb.pdf.

[31] Joanne Richards, “An Institutional History of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE),” Graduate Institute Geneva Institutional Repository, 2014, https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-r9gn-n764.

[32] Niel A. Smith, “Understanding Sri Lanka’s Defeat of the Tamil Tigers by Smith,” Joint Force Quarterly, no. 59 (October 2010): 40–44, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-59/jfq-59_40-44_Smith.pdf?ver=8NrZ-_3wIjxkUc7YJqVKIA%3D%3D.

[33] Sara De Silva, “Change and Continuity in Terrorism: An Examination of the Lifecycle of the Liberation of Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” Publicationslist.org. Thesis, 2013, https://ro.uow.edu.au/articles/thesis/An_examination_of_the_lifecycle_of_The_Liberation_of_Tigers_of_Tamil_Eelam/27663021?file=50373045.

[34] Niel A. Smith, “Understanding Sri Lanka’s Defeat of the Tamil Tigers by Smith,” Joint Force Quarterly, no. 59 (October 2010): 40–44, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-59/jfq-59_40-44_Smith.pdf?ver=8NrZ-_3wIjxkUc7YJqVKIA%3D%3D.

[35] Rashmi Raghav, “Why and How the Tamil Tiger Lost the Battle: LTTE Case Study,” International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research 4, no. 3 (2016): 53–60. https://www.researchpublish.com/upload/book/Why%20and%20how%20the%20Tamil%20Tiger-3462.pdf.

[36] Niel A. Smith, “Understanding Sri Lanka’s Defeat of the Tamil Tigers by Smith,” Joint Force Quarterly, no. 59 (October 2010): 40–44, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-59/jfq-59_40-44_Smith.pdf?ver=8NrZ-_3wIjxkUc7YJqVKIA%3D%3D.

[37] M. M. Fazil and M. A. M. Fowsar, “The End of Sri Lanka’s Civil War and the Fall of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE): A Critical Analysis of the Contributed Factors to the Defeat of the LTTE,” Journal of Politics and Law 13, no. 4 (October 15, 2020): 147, https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v13n4p147.

[38] Niel A. Smith, “Understanding Sri Lanka’s Defeat of the Tamil Tigers by Smith,” Joint Force Quarterly, no. 59 (October 2010): 40–44, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-59/jfq-59_40-44_Smith.pdf?ver=8NrZ-_3wIjxkUc7YJqVKIA%3D%3D.

[39] M. M.Fazil and M. A. M. Fowsar, “The End of Sri Lanka’s Civil War and the Fall of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE): A Critical Analysis of the Contributed Factors to the Defeat of the LTTE,” Journal of Politics and Law 13, no. 4 (October 15, 2020): 147, https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v13n4p147.

[40] Kara Joyce, “Gender Roles and Military Necessity: Women’s Inclusion in the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” Georgetown Security Studies Review 11, no. 1 (August 2023), https://repository.digital.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/1086551.

[41] M. M. Fazil and M. A. M. Fowsar, “The End of Sri Lanka’s Civil War and the Fall of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE): A Critical Analysis of the Contributed Factors to the Defeat of the LTTE,” Journal of Politics and Law 13, no. 4 (October 15, 2020): 147, https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v13n4p147.

[42] Joanne Richards, “An Institutional History of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE),” Graduate Institute Geneva Institutional Repository, 2014, https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-r9gn-n764.

[43] Rashmi Raghav, “Why and How the Tamil Tiger Lost the Battle: LTTE Case Study,” International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research 4, no. 3 (2016): 53–60, https://www.researchpublish.com/upload/book/Why%20and%20how%20the%20Tamil%20Tiger-3462.pdf.

[44] Sara De Silva, “Change and Continuity in Terrorism: An Examination of the Lifecycle of the Liberation of Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” Publicationslist.org. Thesis, 2013, https://ro.uow.edu.au/articles/thesis/An_examination_of_the_lifecycle_of_The_Liberation_of_Tigers_of_Tamil_Eelam/27663021?file=50373045.

[45] Niel A. Smith, “Understanding Sri Lanka’s Defeat of the Tamil Tigers by Smith,” Joint Force Quarterly, no. 59 (October 2010): 40–44, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-59/jfq-59_40-44_Smith.pdf?ver=8NrZ-_3wIjxkUc7YJqVKIA%3D%3D.

[46] Ibid.

[47] M. M. Fazil and M. A. M. Fowsar, “The End of Sri Lanka’s Civil War and the Fall of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE): A Critical Analysis of the Contributed Factors to the Defeat of the LTTE,” Journal of Politics and Law 13, no. 4 (October 15, 2020): 147, https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v13n4p147.

[48] Kara Joyce, “Gender Roles and Military Necessity: Women’s Inclusion in the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” Georgetown Security Studies Review 11, no. 1 (August 2023), https://repository.digital.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/1086551.

[49] Sara De Silva, “Change and Continuity in Terrorism: An Examination of the Lifecycle of the Liberation of Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” Publicationslist.org. Thesis, 2013, https://ro.uow.edu.au/articles/thesis/An_examination_of_the_lifecycle_of_The_Liberation_of_Tigers_of_Tamil_Eelam/27663021?file=50373045.

[50] Niel A. Smith, “Understanding Sri Lanka’s Defeat of the Tamil Tigers by Smith,” Joint Force Quarterly, no. 59 (October 2010): 40–44, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-59/jfq-59_40-44_Smith.pdf?ver=8NrZ-_3wIjxkUc7YJqVKIA%3D%3D.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Rashmi Raghav, “Why and How the Tamil Tiger Lost the Battle: LTTE Case Study,” International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research 4, no. 3 (2016): 53–60, https://www.researchpublish.com/upload/book/Why%20and%20how%20the%20Tamil%20Tiger-3462.pdf.

[53] M. M. Fazil and M. A. M. Fowsar “The End of Sri Lanka’s Civil War and the Fall of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE): A Critical Analysis of the Contributed Factors to the Defeat of the LTTE,” Journal of Politics and Law 13, no. 4 (October 15, 2020): 147, https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v13n4p147.

[54] Niel A. Smith, “Understanding Sri Lanka’s Defeat of the Tamil Tigers by Smith,” Joint Force Quarterly, no. 59 (October 2010): 40–44, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-59/jfq-59_40-44_Smith.pdf?ver=8NrZ-_3wIjxkUc7YJqVKIA%3D%3D.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Mapping Militants Project, “Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam,” 2015, https://doi.org/10.25613/g0k4-wf70.